From Chalkboards to AI

What if AI Gets it Wrong? Teaching Students to Detect Errors and Misleading Models

By Valerie Bennett, Ph.D., Ed.D., and Christine Anne Royce, Ed.D.

Posted on 2026-02-18

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

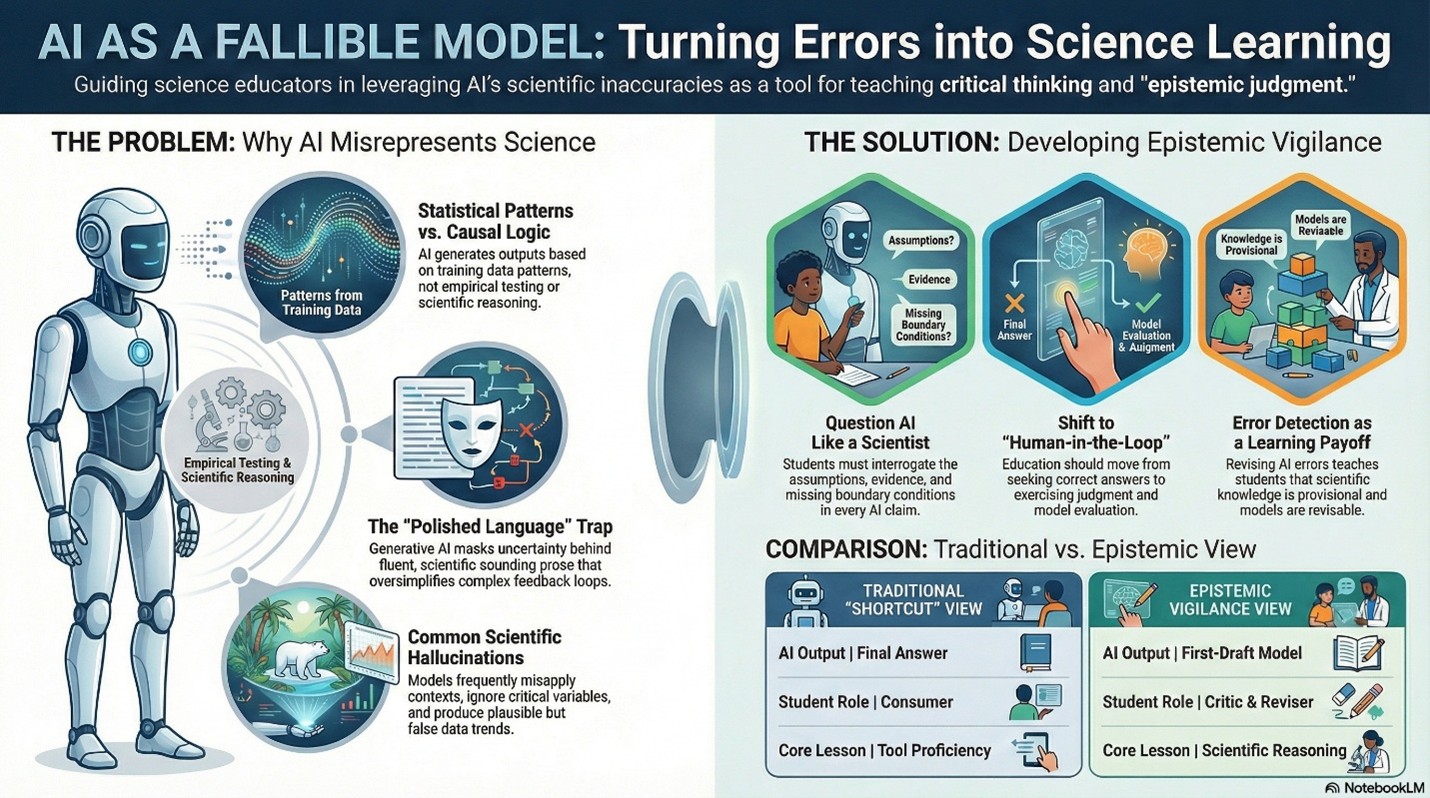

In science classrooms, students are learning to work with a new kind of authority: one that speaks confidently and writes fluently, but is often wrong in subtle ways. Generative AI can produce explanations, graphs, and models that look and sound correct scientifically while quietly violating assumptions, ignoring variables, or overstating certainty. For science educators, this moment is not a crisis—it is an instructional opening.

The core question for 2026 is no longer whether students should use AI but instead is whether students are learning how to evaluate AI-generated science claims the way scientists evaluate all claims. In last month’s blog (https://www.nsta.org/blog/questions-claims-how-ai-intersects-scientific-practice), we examined how AI can intersect with the Science and Engineering Practices. This month, we start to look at the idea that human understanding and judgement are still essential when using AI, even when prompts are well written and information appears correct.

Why AI Gets Science Wrong (and Why That Matters)

Generative AI systems do not reason scientifically. They generate outputs based on statistical patterns in training data, not on causal understanding or empirical testing. Large language models frequently:

- Produce scientifically plausible but incorrect explanations.

- Oversimplify complex systems and feedback loops.

- Hallucinate data trends or misapply models across contexts.

- Mask uncertainty behind polished language.

For science education, these flaws are especially consequential. Science learning depends on model evaluation, evidence-based reasoning, and productive skepticism. If students accept AI outputs uncritically, they bypass the very practices science instruction is meant to cultivate.

Shifting the Goal: From Correct Answers to Epistemic Judgment

Recent scholarship argues that AI literacy in science must move beyond tool use toward epistemic vigilance—the ability to question how knowledge claims are generated, justified, and limited (K–12 AI Education Working Group, 2021; Ng et al., 2023).

In this framing, the use of AI becomes a case study in scientific reasoning rather than a shortcut around it. Students learn to ask:

- What assumptions does this model rely on?

- What evidence supports or contradicts this explanation?

- What variables, mechanisms, or boundary conditions are missing?

- Where might this model fail?

These questions mirror how scientists interrogate any model, computational or otherwise.

Three Classroom Vignettes: Turning AI Errors Into Science Learning

Vignette 1: Middle School Earth Science – Climate Trends

Students ask an AI tool to explain why global temperatures have increased over the past century. The AI produces a smooth explanation focused primarily on carbon dioxide, with a simplified linear trend graph.

The teacher then asks students to compare the AI explanation to real climate datasets and peer-reviewed summaries. Students quickly notice missing elements including feedback loops, aerosols, ocean heat uptake, and regional variability. The class reframes the AI response as a first-draft model and collaboratively revises it.

Learning payoff: Students practice evaluating explanatory adequacy and recognize that scientific models are partial and revisable—not authoritative truths.

Vignette 2: High School Biology – Gene Expression Models

In a genetics unit, students prompt AI to describe how a single gene determines a trait. The AI produces a clear and clean Mendelian explanation.

Using case studies on polygenic traits and epigenetics, students identify where the AI model breaks down. They annotate the AI response, marking assumptions, oversimplifications, and contexts where the model fails.

Learning payoff: Students learn that models are context-dependent and that oversimplified explanations can misrepresent biological reality.

Vignette 3: Physics – Motion and Idealized Systems

Students ask AI to explain projectile motion. The AI provides equations that assume no air resistance and ideal conditions without explicitly stating those assumptions.

The teacher challenges students to design a scenario where the AI explanation would be inaccurate (e.g., lightweight objects, high wind, non-Earth conditions). Students test their predictions using simulations and video analysis.

Learning payoff: Students connect mathematical models to physical assumptions and learn that “wrong” models can still be useful within limits.

Designing for Error Detection, Not Error Avoidance

Recent studies emphasize that engaging students in model critique and uncertainty leads to deeper conceptual understanding and stronger scientific agency (Manz & Suárez, 2018; updated work in Manz et al., 2022). When teachers intentionally surface AI errors, students learn that:

- Authority does not equal accuracy.

- Confidence is not evidence.

- Scientific knowledge is always provisional.

This approach aligns with emerging calls to integrate AI literacy with disciplinary practices rather than teaching it as a standalone skill (Ng et al., 2023).

Equity and Ethics: Who Decides What Counts as "Correct"?

AI models often reflect dominant scientific narratives and datasets, which can marginalize local knowledge, community-based science, or emerging research. Teaching students to detect AI errors also means teaching them to ask whose data and whose assumptions shape AI outputs.

In this way, error detection becomes both a scientific and ethical practice that supports more inclusive and critically conscious science learning.

The Teacher's Role in an AI-Rich Science Classroom

As AI-generated explanations become commonplace, science teachers take on an increasingly vital role as epistemic guides. Their expertise will be most valuable not in competing with AI for answers, but in helping students learn how to evaluate, revise, and frame claims—skills at the heart of high-quality science instruction and strongly aligned with the professional vision advanced by the National Science Teaching Association.

AI Errors Are a Feature, Not a Failure

If AI always got science right, students would have few opportunities to practice real scientific thinking. By treating AI outputs as fallible models rather than final answers, teachers can transform mistakes into moments of sensemaking, critique, and discovery.

In 2026, the most important science lesson may not be how to use AI—but how to question it like a scientist.

The following video and audio synopsis of this blog were generated using Google NotebookLM's features. They have been reviewed for alignment to the blog and accuracy.

References

K–12 AI Education Working Group. (2021). Guidelines for AI education in K–12. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 21(2), 1–31.

Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2023). AI literacy: Definition, teaching, evaluation and ethical issues. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100125.

Manz, E., Renga, I. P., & Aranda, M. L. (2022). Negotiating uncertainty in scientific practice. Science Education, 106(3), 530–553.

Valerie Bennett, Ph.D., Ed.D., is an Assistant Professor in STEM Education at Clark Atlanta University, where she also serves as the Program Director for Graduate Teacher Education and the Director for Educational Technology and Innovation. With more than 25 years of experience and degrees in engineering from Vanderbilt University and Georgia Tech, she focuses on STEM equity for underserved groups. Her research includes AI interventions in STEM education, and she currently co-leads the Noyce NSF grant, works with the AUC Data Science Initiative, and collaborates with Google to address CS workforce diversity and engagement in the Atlanta University Center K–12 community.

Christine Anne Royce, Ed.D., is a past president of the National Science Teaching Association and currently serves as a Professor in Teacher Education and the Co-Director for the MAT in STEM Education at Shippensburg University. Her areas of interest and research include utilizing digital technologies and tools within the classroom, global education, and the integration of children's literature into the science classroom. She is an author of more than 140 publications, including the Science and Children Teaching Through Trade Books column.

This article is part of the blog series From Chalkboards to AI, which focuses on how artificial intelligence can be used in the classroom in support of science as explained and described in A Framework for K–12 Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards.

The mission of NSTA is to transform science education to benefit all through professional learning, partnerships, and advocacy.