From Chalkboards to AI

From Questions to Claims: How AI Intersects with Scientific Practice

By Christine Anne Royce, Ed.D., and Valerie Bennett, Ph.D., Ed.D.

Posted on 2026-01-15

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

There is no doubt that science is dynamic; how we pursue science evolves, and tools and technologies continually improve.

If you are a science teacher, you are likely familiar with the critique of the traditional Scientific Method poster. For years, we have displayed that neat, linear flowchart: Ask a Question -> Hypothesis -> Experiment -> Conclusion. While comforting, this linear model has long since been replaced by the multidimensional Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs). We teach that science is iterative, not linear. However, even our updated understanding of how science is pursued and how the SEPs are employed is being challenged. If you were to walk into a leading research laboratory today, ranging from a biotech firm in Boston to a materials science lab in Berkeley, you would find that the practice of science has evolved into a "Fourth Paradigm," which is a transition from empirical and theoretical science to data-intensive, AI-driven exploration.

The Fourth Paradigm is not new; it emerged in 2009, when a book of the same name was published, focusing on how new knowledge could be acquired through technologies that could manipulate, analyze, and display data.

Here is an overview of the paradigms:

| First Paradigm | Empirical and Observational Methods |

| Second Paradigm | Theoretical Models |

| Third Paradigm | Computational Thinking |

| Fourth Paradigm | Data Intensive (Likely Moving Into AI-Driven Exploration) |

When relying solely on observational approaches, our understanding of the sky was limited to what we could see with the naked eye or, later, with telescopes. The Second Paradigm allows us to predict where different types of astronomical objects would be based on the understanding of theories. Eventually, the Third Paradigm was applied with the mapping and cataloging of the universe began with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which released its most recent dataset this past July, aided by the use of AI in its mission. This further demonstrates the criticality of what the Fourth Paradigm offers the scientific community - the wonder of discovery and the obligation to report it objectively.

The Crossroads of Scientific Pursuit and AI

As educators, we stand at a crossroads. The science we model reflects the empirical methods of the 20th century (the First Paradigm) and even the theoretical models (the Second Paradigm). In addition, science in 2025 is dynamic, data-driven, and, at times, increasingly automated. Understanding these foundational elements is essential; however, to prepare students for the future, we must bridge the gap between traditional inquiry and computational thinking (the Third Paradigm) that is rewriting the rules of discovery. This post explores how AI is changing the research landscape and illustrates how and where the NGSS Science and Engineering Practices can be highlighted.

The Shift: From "Aha!" to Computational Thinking

To understand this shift, we must look at how we approach Asking Questions and Defining Problems (SEP 1). In the traditional model, a hypothesis is a spark of human intuition. A scientist observes a phenomenon and makes a prediction or asks a question to investigate.

While this is an important lesson and practice to develop, science in today’s world often uses massive datasets to develop and run simulations. But what happens when the dataset is too massive for a human brain to process? Not only are computers utilized, but now more than ever AI is also incorporated into this process.

An Example: Physics and Climate Systems and Models

Over 30 years ago, the lead author participated in the Program for Climate Modeling, Diagnosis, and Intercomparison (PCMDI), a summer research program sponsored by the Department of Energy. For the science questions and problems we examined then, there are clear differences in how we as scientists (and students) might approach and use SEP 1, depending on the different Paradigms.

This example highlights a fundamental shift in Asking Questions and Defining Problems:

| Traditional Models (Paradigms 1-3) | Data- and AI-Enhanced Model (Fourth Paradigm) |

|---|---|

Human observation sparks the question. | Pattern detection across massive datasets surfaces questions. |

| Hypothesis driven by intuition and experience | Hypothesis informed by statistical and computational insights. |

| Small, manageable datasets | Datasets too large for human cognition alone |

| Human defines all variables. | AI suggests relationships humans may not notice |

In a traditional science classroom aligned with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Science and Engineering Practice 1 (SEP 1), students often begin by observing a phenomenon—such as rising global temperatures—and asking a focused question like, “How does increased atmospheric carbon dioxide affect Earth’s average temperature?” From there, they form a hypothesis based on prior knowledge, and investigate using a limited dataset or controlled experiment.

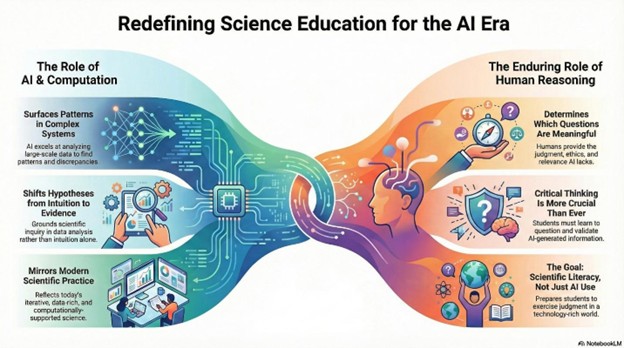

While this approach builds essential skills, it reflects a time when scientific data were small enough for humans to analyze directly. Today, scientists often face a different challenge: When multiple models or analyses produce different results, how do we decide which are the most reliable? Contemporary science increasingly relies on massive datasets and computational tools, including AI, to identify patterns and to reveal alternative interpretations that humans alone might miss. For teachers, this shift highlights that asking questions in modern science is less about making a single prediction and more about interpreting data at scale and exercising informed scientific judgment.

Since a version of PMDI still operates, it is important to note that PCMDI does not determine which models are “correct”; rather, examining trends helps scientists to ask more precise, meaningful questions. In this way, AI and large-scale computation support SEP 1 by augmenting human reasoning, while scientists retain responsibility for defining problems, interpreting results, and determining scientific significance.

For today’s classrooms, it is important to consider where AI is used in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. These key points should be considered, and students should be provided opportunities to discuss them.

For students, this example:

- Reinforces that science is evolving, not abandoning core practices (i.e., asking questions)

- Shows that question-asking is still human-centered, but increasingly data-informed.

- Helps them understand why AI outputs must be interpreted, not accepted at face value.

Furthermore, examples such as these directly support the ideas that:

- AI contributes to science by identifying probabilistic patterns in vast datasets, while humans remain responsible for defining purpose, validity, and meaning.

- The AI/computation role is not “verifying truth,” but detecting patterns and summarizing performance across huge datasets, which then helps scientists ask better questions and refine hypotheses.

Computational Thinking Takes Center Stage

In the Fourth Paradigm, the practice of Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking (SEP 5) takes center stage. Algorithms mine massive datasets to identify patterns that no human could detect. This changes the origin of the hypothesis--instead of arising solely from human intuition, hypotheses are generated by AI systems identifying high-dimensional relationships, which scientists then validate.

Obtaining and Evaluating Information

How do we bring these shifts into the classroom? We engage in Citizen Science 2.0, where the student's role focuses on Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information (SEP 8).

As AI tools increasingly support scientific work, the Science and Engineering Practices remind us that humans must remain firmly in the loop. The new model is "Human-in-the-Loop (HITL), which refers to a system or process in which a human actively participates in the operation, supervision, or decision-making of an automated or AI system (Stryker, n.d.). HITL ensures that human judgment is used to address ambiguity, bias, accuracy, ethical considerations, and accountability.

While AI can surface patterns, generate models, or organize evidence at a scale beyond human capacity, it cannot independently judge relevance, resolve ambiguity, or evaluate ethical implications. Practices such as constructing explanations, engaging in argument from evidence, and defining meaningful questions require human reasoning, disciplinary knowledge, and values. HITL approaches ensure that AI enhances efficiency and insight without displacing the critical judgment at the heart of scientific practice.

Examples of Citizen Science 2.0 projects that can help teach students both the value of computational thinking and AI as well as where human judgment is still needed, include:

- Penguin Watch: AI counts the visible penguins; students identify those hiding behind rocks, validating the system model.

- Planet Hunters TESS: Students inspect light curves to find planetary transits that automated pipelines missed.

Participating in these projects transitions students from consumers of information to producers of knowledge, reinforcing the Nature of Science and that scientific knowledge is open to revision in light of new evidence. Together, these examples illustrate how AI-supported inquiry strengthens SEPs 6, 7, and 8 by shifting student work from information consumption to explanation, evaluation, and evidence-based communication.

Caution: The Need for Due Diligence of Cross-Referencing AI Output with Primary Sources

As with any tale, strategy, or approach, there is always a need for caution and skepticism. This example is not a critique of computational science or data-driven inquiry, but a caution specific to generative AI language models, which produce outputs based on probabilistic patterns rather than verified scientific evidence. To teach the importance of Arguing from Evidence (SEP7) and Evaluating Information (SEP 8), tell your students about "Vegetative Electron Microscopy" (Snoswell, et al., 2025).

Let’s take a step back first. Many years ago, a spoof circulated on the internet asking students to “Ban dihydrogen monoxide (DHMO).” As a science fair project, a student wrote a “petition” to ban DHMO and cited all the dangers associated with it. This spoof has since been used to discuss the need to verify information and not believe everything you read. We now enter the age of AI with a modern version and a cautionary tale that may be considered even more problematic.

In 2024, the term "Vegetative Electron Microscopy" appeared in scientific papers because an AI "hallucinated" a connection between two unrelated words it digitally scanned and scraped from old data. It is actually an interesting scenario when we consider how often we use information that was gathered in similar ways. It produced a "digital fossil" and replicates itself because the term now exists within LLMs (Snoswell et al., 2025). This serves as a powerful lesson: AI language models generate responses based on the statistical probability of words and patterns, not on direct verification of factual accuracy. Teaching students to cross-reference AI claims with primary sources is a new requirement for scientific literacy.

What This Means for Teachers

- Teach the practices, not just the tools: AI should be introduced as a support for engaging in the Science and Engineering Practices, not as a shortcut to answers or conclusions.

- Design questions that require judgment: Use AI-supported datasets or outputs as starting points, then ask students to interpret, critique, and justify claims using evidence.

- Make evaluation explicit: Help students practice cross-referencing AI-generated information with primary sources to strengthen SEP 7 (Engaging in Argument from Evidence) and SEP 8 (Evaluating Information).

- Keep humans in the loop: Emphasize that ethical reasoning, relevance, and meaning-making remain human responsibilities, even when computational tools are involved.

Conclusion

The goal is not to turn every student into a computer scientist, nor to utilize AI in every investigation or scientific pursuit, but to cultivate citizens who are literate in the modern scientific enterprise. By embracing the Fourth Paradigm, through data-driven inquiry, computational thinking, and ethical critique, we empower the next generation to not only use these powerful tools but to shape them responsibly.

The following video and audio synopsis of this blog were generated using Google NotebookLM's features. They have been reviewed for alignment to the blog and accuracy.

References

Sloan Digital Sky Survey. (n.d.). Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). https://www.sdss.org/

Snoswell, A. J., Witzenberger, K., & El Masri, R. (2025, April 25). A strange phrase keeps turning up in scientific papers, but why? ScienceAlert. https://www.sciencealert.com/a-strange-phrase-keeps-turning-up-in-scientific-papers-but-why

Stryker, C. (n.d.). What is human-in-the-loop? IBM Think. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/human-in-the-loop

Szalay, A. (2012). Data-driven discovery in science: The fourth paradigm [Conference paper]. NITRD Symposium 2012. https://www.nitrd.gov/historical/nitrdsymposium-2012/speakers/documents/szalay.pdf

University of California, Northridge. (n.d.). Dihydrogen monoxide research division (DHMO). https://www.csun.edu/science/ref/humor/dhmo.html

Christine Anne Royce, Ed.D., is a past president of the National Science Teaching Association and currently serves as a Professor in Teacher Education and the Co-Director for the MAT in STEM Education at Shippensburg University. Her areas of interest and research include utilizing digital technologies and tools within the classroom, global education, and the integration of children's literature into the science classroom. She is an author of more than 140 publications, including the Science and Children Teaching Through Trade Books column.

Valerie Bennett, Ph.D., Ed.D., is an Assistant Professor in STEM Education at Clark Atlanta University, where she also serves as the Program Director for Graduate Teacher Education and the Director for Educational Technology and Innovation. With more than 25 years of experience and degrees in engineering from Vanderbilt University and Georgia Tech, she focuses on STEM equity for underserved groups. Her research includes AI interventions in STEM education, and she currently co-leads the Noyce NSF grant, works with the AUC Data Science Initiative, and collaborates with Google to address CS workforce diversity and engagement in the Atlanta University Center K–12 community.

This article is part of the blog series From Chalkboards to AI, which focuses on how artificial intelligence can be used in the classroom in support of science as explained and described in A Framework for K–12 Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards.

The mission of NSTA is to transform science education to benefit all through professional learning, partnerships, and advocacy.