Interdisciplinary Ideas

Teaching Nonfiction Text Structure

Bringing other subjects into the science classroom

I start the school year with a lesson on nonfiction text structure. In small groups, students are given a variety of nonfiction science books. They are tasked with observing the books to determine the various forms of text structure. Then, using this information, they infer the author’s purpose for structuring the book in this way. We then discuss that this is a prereading strategy, called surveying the text, and is the first of many methods they will learn over the year to help improve their reading comprehension.

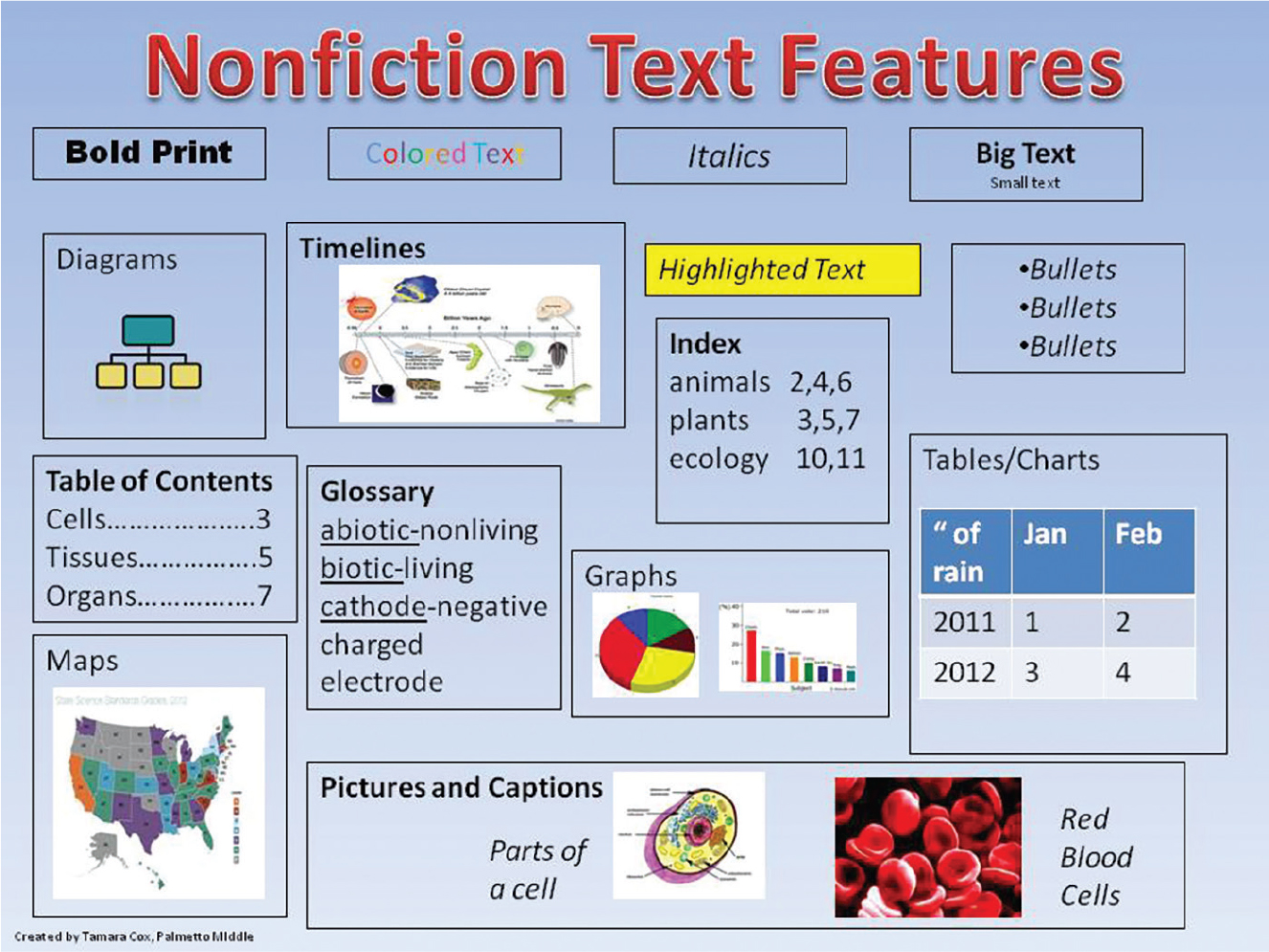

Alexandra Bluestein (2010), a language arts curriculum instructional leader, emphasizes the role that text features can have in helping students sort out the most important information in the text. She explains how text features help build the bridge between nonfiction text and comprehension. Knowing the importance of text features before beginning the book observation activity, I ask students to give examples of text features and text structures because I have found that they often confuse the terms. By listing some text features on the board, such as the table of contents, graphs, and bold font, students see that text features are components, or organizational features, of the text (Figure 1).

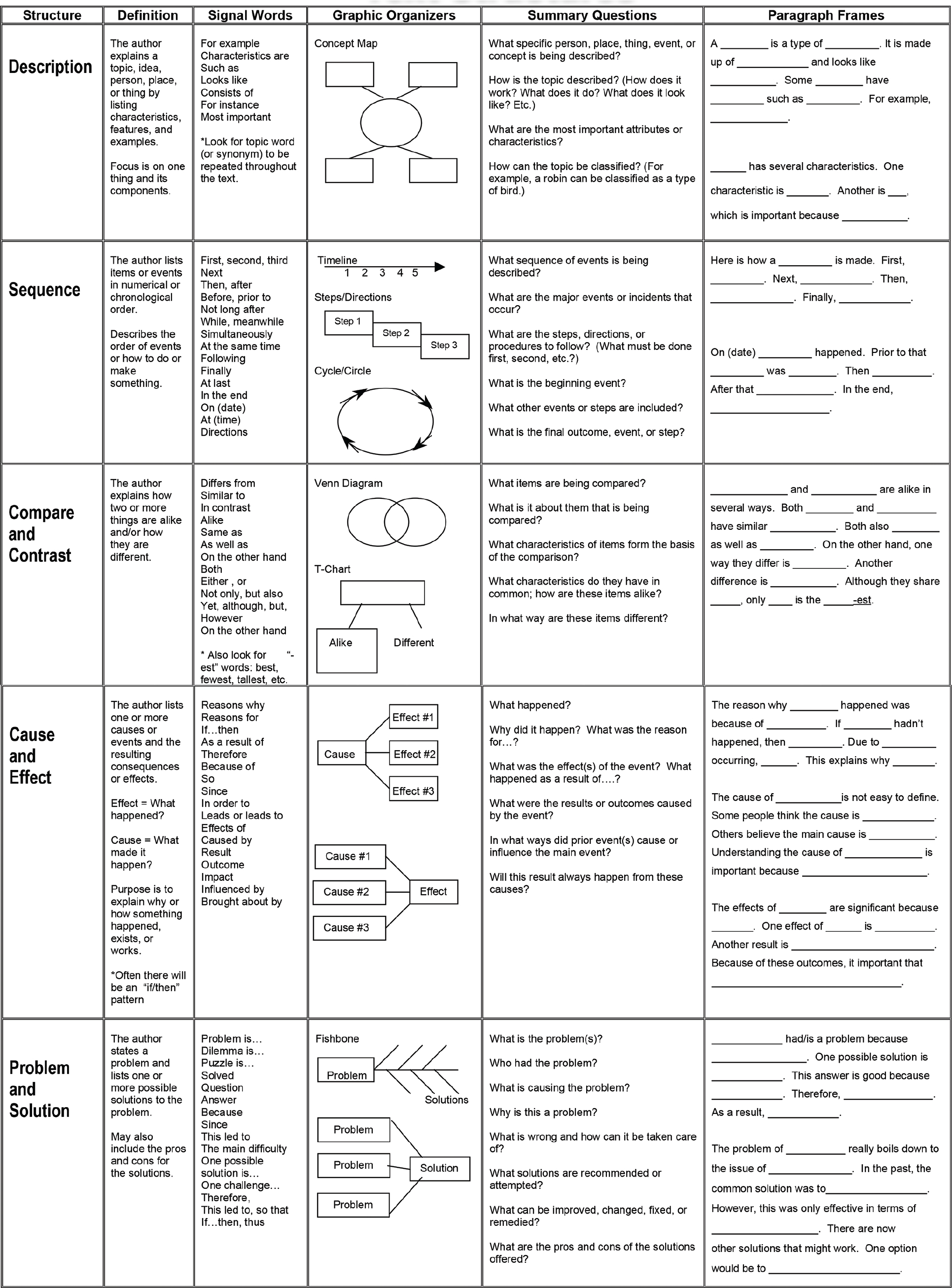

Text structure is an author’s method of organizing the information (Figure 2). There are thought to be five common text structures: description, cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution, and sequence (Meyer 1985). When doing the book observation activity, students also find that there are other text structures, such as organizing information alphabetically and using a question-and-answer format. My goal is not for students to memorize the forms of text structure, but to be able to identify an organizational method used by an author.

To help students see that text features and text structure are universal, I also include nonfiction books in foreign languages. Students find this engaging and quickly realize that text structure can still be determined if a book is written in a different language. To get books for this activity, I ask my school’s world language and English language learner (ELL) teachers to borrow some nonfiction books from their class libraries. This strategy also helps my ELL students feel connected to this lesson and enhances their comprehension of the topics of the books. I once worked with a group, that included an ELL student; he watched members of his group struggle to read the title of a book in Spanish. The ELL student, who did not often speak in class, smiled as he pronounced terremoto (earthquake) for his group members with rolling Rs. According to Kristina Robertson (2008), for ELL students who already face the challenges of a new language, it is essential to give them a head start on understanding vocabulary and content by first helping understand nonfiction text structure. She emphasizes the importance of teachers giving direct, clear instruction on how nonfiction text is structured and what good readers do to get information from the text. Teachers should also give students the opportunity to practice and provide students time to work with peers to increase their comprehension.

I purposely do the book observation activity (Figure 3) before starting a content-based unit so that students can practice the skill of understanding text structure without focusing on reading the actual text. This purposeful practice also allows my students to infer why authors may choose to organize their writing in a certain way. For example, some of the books that students use in this activity include nonfiction books about dinosaurs with three different text structures; two are organized alphabetically, one chronologically, and another compares and contrasts dinosaur features. When discussing why the authors chose to present the information in these varying ways, one student shared that if he were to write a dinosaur book, he would want to write it with a different text structure so that he could approach it in a unique way. This comment showed me that he understood the importance of text structure and that he was starting to think like a writer. Throughout the school year, we revisit text structure whenever we use a new book or website. Each time, the preview is a little shorter as students build independence around identifying the organization of the text.

In science class, I often wish I had more time to teach and expand on the concepts that students are learning. It may seem like teaching students how to approach nonfiction reading is another task to accomplish in an already too-full curriculum; however, taking the time to teach students these skills can save time in the long run by helping them have improved comprehension. The more that students build a routine around reading, the more likely this is to become a habit in the future.