Elementary | Formative Assessment Probe

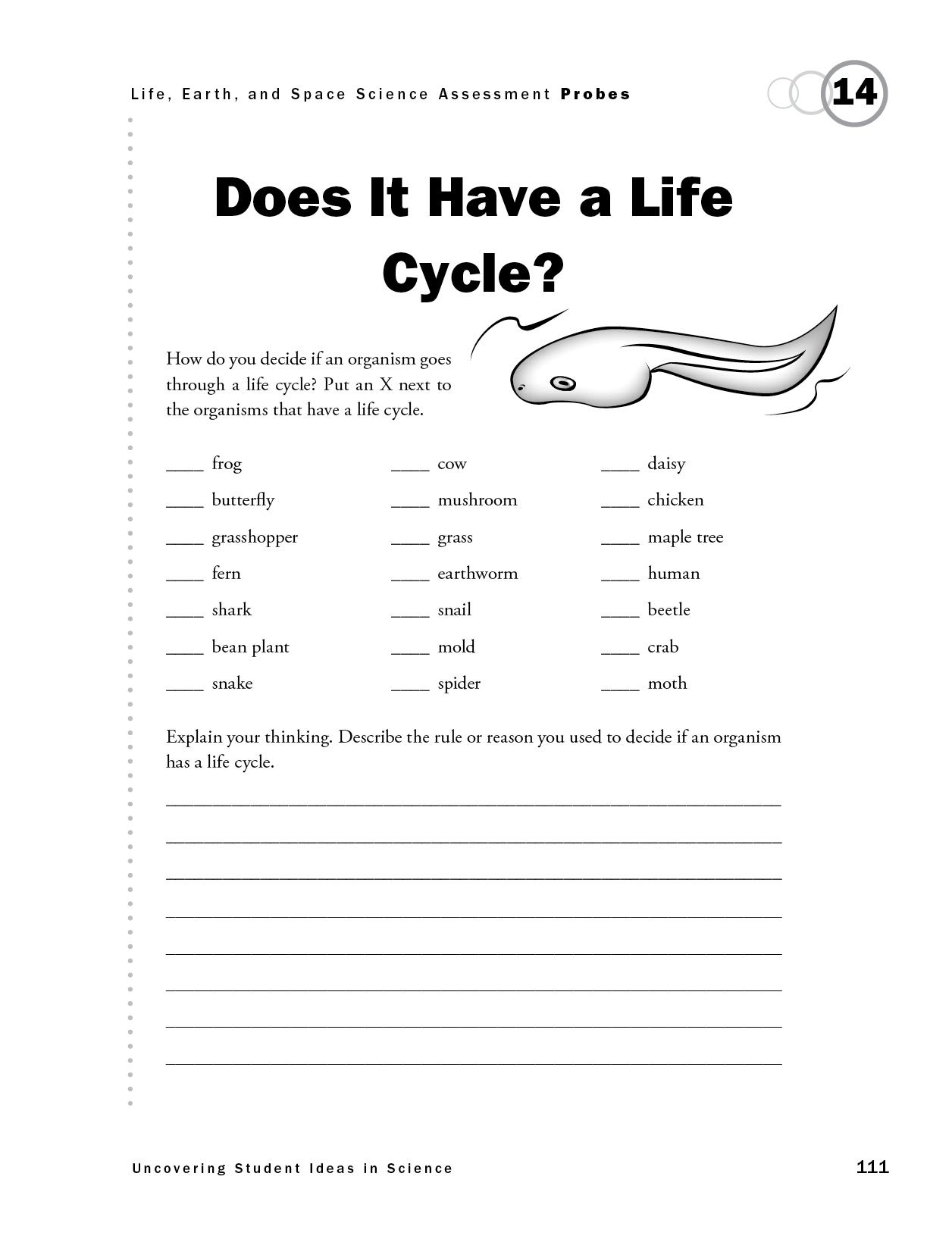

Does It Have a Life Cycle?

By Page Keeley

Assessment Life Science Elementary Grade 3

Sensemaking Checklist

This is the new updated edition of the first book in the bestselling Uncovering Student Ideas in Science series. Like the first edition of volume 1, this book helps pinpoint what your students know (or think they know) so you can monitor their learning and adjust your teaching accordingly. Loaded with classroom-friendly features you can use immediately, the book includes 25 “probes”—brief, easily administered formative assessments designed to understand your students’ thinking about 60 core science concepts.

Purpose

The purpose of this assessment probe is to elicit students’ ideas about life cycles. The probe can be used to determine whether students recognize that although life cycles vary in length and developmental stages, all multicellular organisms go through a life cycle.

Type of Probe

Justified List

Related Concepts

development, growth, life cycle, living vs. nonliving, reproduction

Explanation

All of the organisms on the list go through a life cycle. The entire lifespan of an organism, including the birth of a new generation of offspring, is called a life cycle. A life cycle typically includes fertilization and development of the embryo or embryo-like stage, birth or emergence, growth and development into an adult, reproduction, and death of the adult. It is cyclic because most adult organisms reproduce and give rise to new offspring, which keep the cycle going. At some stage in the life cycle of multicellular organisms, they stop reproducing and eventually die.

Stages of the life cycle vary among different types of organisms. For example, some organisms undergo changes during their early development in which the developing organism looks very different from the adult (e.g., butterfly, frog, beetle). Other organisms give rise to offspring with developing features that are similar to adult features (e.g., shark, human, maple tree, cow). Some life cycles are short (measured in days) and some are long (measured in years). Other differences include details of fertilization and zygote development.

Curricular and Instructional Considerations

Elementary Students

Elementary school students observe a variety of living organisms in the classroom to learn about their life cycles. Direct experiences include raising butterflies, frogs, and plants to study their life cycles. Representations are often used to sequence life cycles and to compare and contrast different types of cycles, such as complete and incomplete metamorphosis in insects. Studying the life cycle of an organism helps children understand the continuity of life.

Middle School Students

In middle school, students learn about fertilization (including pollination) as the beginning of an animal or plant’s life cycle. Changes in the development of a plant or animal embryo are examined, including similarities between development of different species of plant or animal embryos. Details of human reproduction and development are introduced at the middle school level. At this level, students begin to link the idea of cell division to growth of an organism.

High School Students

In high school, biology students build on their basic K–8 understanding of sexual reproduction and development to focus on the haploid and diploid cellular details. They learn about complex life cycles of certain types of animals, fungi, and vascular and nonvascular plants, including alternation of generations (alternation of sexual and asexual reproduction) and sexual variations, such as parthenogenesis (development of an organism from an unfertilized egg), changing from male to female or vice versa, and hermaphrodism (having both male and female reproductive organs).

Administering the Probe

For younger students, you may choose to reduce the number of organisms on the list and/or include pictures of each. Remove any organisms on the list that students may be unfamiliar with. Consider adding additional items that students may have encountered in their local environment. This probe could be used with a card sort: Have students group items into those with life cycles and those without, and listen carefully to their reasoning. Extend the probe even further by asking students to describe the stages of the life cycle for each item they select. Listen carefully for indications that students recognize a cyclic process that includes being born, reproduction, and death, and do not just focus on the features of the developmental change each organism on the list goes through.

Related Research

- In a study that investigated 10- to 14-year-old children’s ideas about the continuity of life, most could correctly sequence pictures of seed germination, but 66% did not view the seed as alive and 19% did not understand the continuity of life from seed to seedling (Driver et al. 1994, p. 49).

- Some studies indicate that children fail to consider death as part of a life cycle (Driver et al. 1994).

- As students investigate the life cycles of organisms, teachers might observe that young children do not understand the continuity of life from, for example, seed to seedling or larvae to pupae to adult (NRC 1996, p. 128).

- Some K–8 students tend to equate life cycles only with the examples they observed in school, such as certain types of plant, butterfly, frog, or mealworm life cycles or organisms that are similar to those they studied. When students encounter organisms that are different from the ones they studied, they fail to recognize that all organisms have a life cycle (Authors’ analysis of student work).

Related NSTA Resources

Ansberry, K., and E. Morgan. 2007. Loco beans. In More picture-perfect science lessons, 65–73. Arlington, VA: NSTA Press.

Cavallo, A. 2005. Cycling through plants. Science and Children (Apr./May): 22–27.

Driver, R., A. Squires, P. Rushworth, and V. Wood- Robinson. 1994. Making sense of secondary science: Research into children’s ideas. London and New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Keeley, P. 2005. Science curriculum topic study: Bridging the gap between standards and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Pliske, C. 2000. Natural cycles: Coming full circle. Science and Children (Mar.): 35–40.

Schussler, E., and J. Winslow. 2007. Drawing on students’ knowledge. Science and Children (Jan.): 40–44.

Suggestions for Instruction and Assessment

- When students make observations of a particular plant or animal’s life cycle, be explicit in developing the generalization that all animals and plants go through a life cycle, even though details of their cycles differ.

- Use the term continuity of life along with life cycle so that the bigger idea of life continuing from generation to generation is emphasized. Teaching the stages in the life of different organisms is part of the idea of life cycles but can overshadow the more important idea of continuity if not explicitly addressed.

- Observe directly, if possible, or provide multiple visual examples of life cycles that differ in details. Have elementary school students identify the common pattern of birth, growth and development, reproduction, and death. Have middle and high school students identify fertilization, embryo development, birth or emergence, growth and development, reproduction, aging, and death.

- Avoid linear representations of life cycle stages that do not imply a cyclic process. Representations used should portray the continuity of life.

- So that students do not develop the misconception that life cycles begin after an egg hatches, a seedling emerges, or an animal gives birth, explicitly target the idea that seeds and eggs are alive and that there is a developing organism inside some animals.

- Emphasize the diversity among species in the details of their life cycles while pointing out the commonalities, not only between different animal species or different plant species, but between animal and plant species as well. Provide opportunities throughout students’ K–12 experiences to examine a variety of life cycles, including organisms they may not be as familiar with.