#OrganelleWars: A Model for Using Social Media in the Science Classroom

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-05

Given the current political fervor over the candidacies of the people attempting to become our next president, now seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most successful projects I have had the good fortune of incorporating into my freshman biology classroom.

Launching a Model Organelle Campaign

In the fall of 2011, I had reached the point of the school year when it was time to start teaching my freshman biology students about the cell and its organelles. In my 14 years of teaching to that point, I had tried all types of different approaches to try and bring the cell alive for my students. I had tried direct instruction, having students build models of the cell, asking them to make analogies comparing the cell to a city, having them give presentations on individual organelles, even putting on a pretend radio show in class, and finally making fake Facebook pages on paper for each organelle. So as I prepared to begin the cell unit for the fourteenth time, I went to the Internet looking for inspiration (teachers are nothing if not good thieves, after all). One project I discovered came from Marna Chamberlain at Piedmont High School in California. The idea was to have students run an election campaign to get an organelle elected the most important organelle in the cell. The project involved promoting an organelle in class through the use of posters, brochures, and a speech. In addition to promoting their own organelle, students also had to smear at least five other organelles. This last requirement was designed, of course, to ensure that students researched the functions of other organelles in the cell as they worked on promoting their own. After a correspondence with Ms. Chamberlain, I decided to give the project a try.

Before getting started, I made one tweak to the project from its original incarnation, and that was to add a social media component to it. I had noticed, as most educators I work with had at that point, that students were often more preoccupied with their social media accounts than they were with their school work. My thought was that if I could bring school to where students were already spending a lot of their time, I might be able to capture their interest better than I had been able to in the past. The requirement for the social media component, which was optional for students to create, was that any account had to be a fake account in the name of the organelle. This was important in keeping the identities of my students anonymous and in keeping in line with the social media policy of my school district.

Moderate Success in Year One

The first year of the project went pretty well. My students made some great campaign posters and flyers, to the point that my classroom was covered in both promotional and smear posters. The social media component was fun, but the only people following any students’ accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Tumblr, were other students or myself. The proof of the effectiveness of this project, of course, would be in my students’ results on their end-of-unit assessment. I was concerned that although the project was fun, that perhaps they had not learned as much about cell organelles as in the past, since they had only been required to focus on six organelles. Students had been made aware that they were responsible for being able to identify and know the function of all of the organelles assigned in the project, but I was still nervous. In the end, however, students performed as well on the cell unit test in 2011 as they had in all my previous years, only this time they enjoyed and became engaged with the content. The project was successful enough that I decided to stick with it and try it again the following year.

Year Two: The Scientific Community Embraces the Concept

One of the keys to the project in 2012 was that it was a presidential election year, and it was the first campaign to truly use social media. My students were already naturally excited about the election process. The classroom was buzzing with activity, as students started creating campaign t-shirts, buttons, and stickers, in addition to the posters and brochures. They also created their Twitter accounts for their organelles, such as @GolgiBody2012 and @MightyMito42.

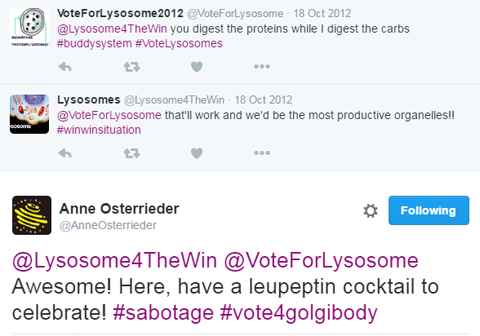

Then a funny thing happened. Someone I didn’t know started tweeting with my Golgi Body group. My first reaction was of course to determine who this person was, and I was initially quite nervous that a complete stranger had somehow found our little project on Twitter. But my apprehension turned to delight when the stranger turned out to be Dr. Anne Osterrieder (@AnneOsterrieder), a plant biologist who is an expert on the Golgi Body and a lecturer/researcher at Oxford Brookes University in England. Apparently Dr. Osterrieder had found one of my students’ Golgi Body Twitter accounts during a Twitter search for any relevant new tweets with content related to her organelle of interest.

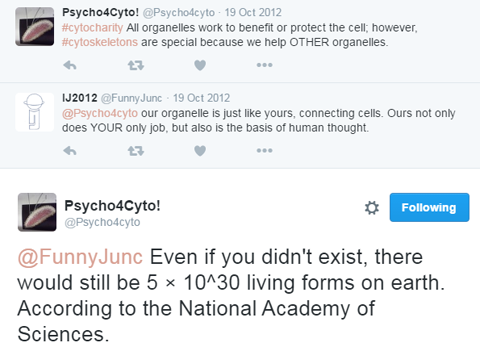

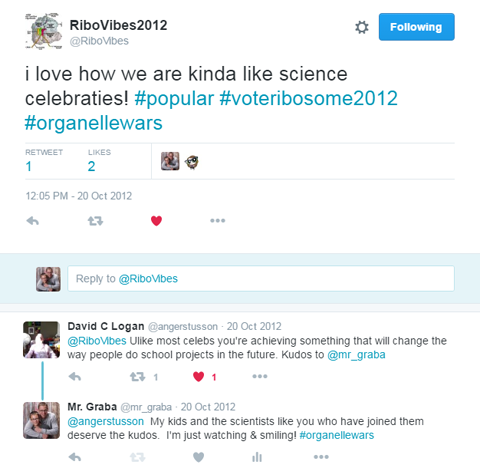

From those initial tweets, the project exploded. A colleague of Dr. Osterrieder’s at Oxford Brookes University, Dr. John Runions (@JohnRunions), also began tweeting with my students. Dr. Runions gave our project the hashtag #organellewars on Twitter. Since then, that has become the name this project goes by in my classroom and online. Dr. Runions also has his own BBC radio show, where he goes by the alias Dr. Molecule, which he used to talk about my students and their project on one of his shows. Dr. David Logan (@angerstusson) from the Universite d’Angers in France, a plant biology researcher and self-described mitochondriac, also began tweeting with my students, helping to promote the mitochondria groups and smear the others. Soon other biologists from all over North America and Europe began tweeting with my students. The buzz the project created within the classroom and the school was incredible. My students were tweeting about organelles with scientists from Europe late at night on the weekend. In the past I had been lucky to get them to think about organelles at all other than when they were physically present in the classroom, but now they were actively engaged in learning about organelles beyond the four walls of my classroom, on a weekend, because they wanted to!

A Lesson in the Nature of Science

The results of the project the second time around went far deeper than I ever expected. Not only did my students learn about organelles, they learned far more important lessons about social media and science as well. The fact that this time around with the project there were experts on organelles interacting with my students, calling them out when they posted erroneous information, or asking them questions that inspired my students to d

ig deeper after they posted very superficial tweets regarding their organelle, gave my students an authentic audience. They were motivated to make sure that what they were posting was legitimate, appropriate, and able to be cited with reliable resources. I heard discussions among students about having been called out by a scientist online after having posted incorrect information about an organelle and needing to be careful about what they typed before hitting the “Tweet” button. Learning to have that filter before hitting “Tweet” or “Post” is an important skill for this generation to learn at a young age.

One point that I made very early on, after people from around the globe began interacting with us, was the far-reaching and very public nature of social media such as Twitter. Teenagers in general have a tough time grasping this concept. I think this is generally because the only people who interact with them online are typically their very limited social circle. That does not mean, however, that others outside of their small group of friends cannot see what their online activity looks like. It is especially important for the current generation of students to learn this lesson at an early age. College admissions counselors and future employers look at social media accounts to get a better understanding of the people they are admitting or hiring. Something that excites me is that these students now have a positive social media footprint to share with anyone who wants to start looking at their social media accounts.

Students See Scientists in a New Light

My students’ perceptions of scientists also changed from the stereotypes they brought with them into my classroom at the beginning of the year. Most students had the preconceived idea that scientists were boring old men in lab coats and goggles hidden away in a sterile lab all day long. By the end of the project, they were able to see that many scientists are actually vibrant, witty, young men and women who love science and their research, but also like doing the same kinds of things my students and everyone else enjoy.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

Guest Blogger Brad Graba is an AP Biology Teacher at William Fremd High School in Palatine, Illinois.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

5th Annual STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

- Denver, Colorado: July 27–29

2017 Area Conferences

- Baltimore, Maryland: October 5–7

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin: November 9–11

- New Orleans, Louisiana: November 30–December 2

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA

Given the current political fervor over the candidacies of the people attempting to become our next president, now seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most successful projects I have had the good fortune of incorporating into my freshman biology classroom.

Launching a Model Organelle Campaign

Learning Early About STEM Careers Through CTE

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2016-05-05

Students at Camp Ernst Middle School in Burlington, Kentucky, participate in technology leadership camps. Next year, they can take a CTE course in Digital Literacy for high school credit. Photo credit: Kristen Franks

Career and Technical Education (CTE), long the bastion of U.S. high schools, is becoming more common in middle schools and linked with science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) courses. Virginia’s Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) is one supporter, offering middle level CTE courses in Technology and Engineering Education, Business and Information Technology, and Family and Consumer Sciences. “We’re getting [students] engaged at an early age,” says Scott Settar, program manager for Technology and Engineering Education and STEAM Integration. “We’re rewriting the middle school Business and Information Technology courses with more coding, programming, and networking opportunities,” he reports. The CTE courses “focus on the technical application of many career pathways, the design process, and 21st-century skills.

“National research has shown that by grades 5–7, students lose interest in individual [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] STEM content areas,” so students at all grade levels “need to understand why these disciplines are important and relevant” because “upcoming STEM jobs will be in this area,” he contends. “The general consensus across the nation is that Technology and Engineering Education and Business and Information Technology are moving toward a STEAM focus, STEAM integration.”

In FCPS, “Technology and Engineering Education– and Business and Information Technology–related areas—coding, technology, engineering—[ have] almost a K–12 implementation,” observes Rachael Domer, FCPS STEAM Resource Teacher and a former CTE middle school Technology and Engineering teacher. “There’s a new focus on STEAM at the elementary level, exposing students to coding, engineering, and general problem solving.”

She notes that in FCPS, the seventh- grade technology and engineering education course is now called Engineering, Design, and Modeling, and the eighth-grade course has become Engineering Stimulation and Fabrication. “The idea behind the name change is to have the courses speak for themselves. The previous names were too broad,” she observes, adding that these semester- long courses allow students to take two CTE courses each year.

Domer says she talks to teachers of grades 4–6 about CTE course offerings at the high school level so “teachers understand what the end product is” and how familiarity with the engineering design process “will help students in middle school and high school.”

“We talk about CTE in general and connected to STEM education and providing relevant experiences for students, engaging them and inspiring them in learning. With [standardized] testing, we’ve kind of lost this. CTE is moving [back] in that direction,” concludes Settar.

STEM Career Pathways

“Middle school—that’s where the disconnect happens,” says Sunni Stecher, Middle School CTE Consultant for the Sonoma County Office of Education (SCOE) in Santa Rosa, California. With SCOE funds, 13 county schools offer Middle School Career Exploration activities.

Through a partnership of the CTE Foundation and the John Jordan Foundation, SCOE’s CTE department offers free Step-Up Classes—“mini CTE classes”—to middle school students, says Stecher. Step-Up Classes are taught by CTE teachers in their regular high school classrooms. “[They] give students experience with fun classes to motivate them to go to high school and get familiar with career pathways,” she explains.

“We’re trying to focus on high-wage, high-need [subjects] for our area,” such as agriculture and manufacturing. Past topics have included Advanced Technology and Manufacturing, Sonoma Specialties (wine and food), Health and Wellness, Agriculture, Construction, and Green Services, which covers solar and geothermal energy, green technology, agriculture, and alternative fuels.

“The teachers love teaching those classes; they love the exuberance of middle school students. The students are very engaged,” Stecher reports. In course evaluations, 95% of students rate the classes highly, and “the teachers come back every year,” she relates.

SCOE also helps organize a Construction Expo, a free event for middle and high school students staged by the North Coast Builders Exchange, a not-for-profit association serving the construction industry in the California North Coast area. “The kids get to use equipment, do hands-on welding…We get a huge response,” she reports.

Programs like these can be key to attracting students to STEM careers. “Districts need to build career exploration activities into their infrastructure, devote time to it in school,” she contends.

Preparing for High School

“I teach technology courses for middle school and feel passionate about preparing students for CTE,” says Kristen Franks, technology teacher at Camp Ernst Middle School in Burlington, Kentucky. “I will be teaching a high school–credit class (Digital Literacy) next year to eighth graders. The course is a prerequisite for many career pathways that our sister high school offers. As a former high school teacher, I understand the importance of CTE classes and am driven to support our students at the middle school level. There are so many opportunities in high school, and it is crucial for students to get a head start.”

Students in the Digital Literacy course “can go into programming, computer science, digital design, or web development. It’s amazing what opportunities will be available to them,” Franks maintains.

Having CTE at the middle level is important because in high school, CTE courses often “conflict with student schedules, which can include dual enrollment, AP courses, internships, band, and choir. It’s a struggle to get [students] to complete a pathway,” Franks allows. “Hook them early…[so they can] take advanced CTE classes before they leave high school,” she advises.

“The disconnect between middle and high school can’t be like that anymore… We’re all on the same team,” she asserts. She advises middle school CTE teachers to tell high school CTE teachers, “you want to prepare kids for their schools…Having these relationships will change everything.”

Franks notes one obstacle for middle school teachers who want to teach high school CTE courses is that their certification “ends with eighth grade, so they’re not certified to teach a high school-level CTE course…It’s sad that a certification is holding them back. It’s holding the kids back,” she asserts. “Hopefully this will change as they see the successes in middle school.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Cell Division and Differentation

Looking for free resources and finding many worthy webinars and articles

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2016-04-30

It is always a thrill to meet the authors who have written the articles in Science and Children that I’ve found so helpful, and useful enough to share. At the Elementary Extravaganza event at the 2016 NSTA national conference in Nashville

It is always a thrill to meet the authors who have written the articles in Science and Children that I’ve found so helpful, and useful enough to share. At the Elementary Extravaganza event at the 2016 NSTA national conference in Nashville  I met Joseph Robinson, author of “How We Know What We Know: Cultivating scientific reasoning among preschool students with cars and ramps” (January 2016). Judith Lederman, author and co-author of several articles about the Nature of Science, was also in the house! They were just two of the many science educators who contribute to Science and Children and the other NSTA journals.

I met Joseph Robinson, author of “How We Know What We Know: Cultivating scientific reasoning among preschool students with cars and ramps” (January 2016). Judith Lederman, author and co-author of several articles about the Nature of Science, was also in the house! They were just two of the many science educators who contribute to Science and Children and the other NSTA journals.

I share my copy of the journal with colleagues at the program where I teach and recommend specific articles to others. You can do the same! Have you been introduced to the NSTA Learning Center? It is an online center for finding all kinds of resources:

Audio & Video

Audio & Video- Books & Chapters

- Events (In-Person)

- Forums

- Do-It-Yourself Learning

- Journal Articles & Lesson Plans

- Online Course Providers

- Online Events & Courses

- Web Seminars by Sponsor

- Browse Articles by Journal

And you can search by keyword and author! Professors at over 90 colleges and universities across the United States and Canada are using NSTA resources and the NSTA Learning Center as their online textbook when teaching science pre-service teachers. You can learn how through the archived webinar, “The NSTA Learning Center: A Tool to Develop Science Pre-Service Teachers.”

Webinars are a good way to get an introduction to the more than 12,000 resources of the Learning Center. Webinars are archived after they happen live so you can access them at a later time or again. Here are two—one that is coming up and one that you can find in the archives.

Web Seminar: The NSTA Learning Center: Personalized Professional Learning in Collaboration with Other Colleagues, May 12, 2016: Join us for this interactive web seminar to get a detailed look at the Learning Center and discover its resources and professional learning tools that you can begin using immediately.

This program is designed for educators of grades K–12, especially those who are new to the Learning Center. All participants will receive a certificate of participation and 100 Learning Center activity points for attending and completing the end-of-program evaluation. An archive and related PowerPoint presentation will be available at the end of the program.

Web Seminar: The NSTA Learning Center: A Tool to Develop Science Pre-Service Teachers, April 28, 2016: Professors at over 90 colleges and universities across the United States and Canada are using NSTA resources and the NSTA Learning Center as their online textbook when teaching science pre-service teachers. Join us on Thursday, April 28, to learn how you can create a blended learning experience for the teacher candidates you teach by leveraging NSTA resources with the Learning Center’s online community. This web seminar is designed for professors who teach science pre-service teachers at universities and colleges. All participants will receive a certificate of participation and 100 Learning Center activity points for attending and completing the post-seminar evaluation. An archive and presentation slides will be available at the end of the program.

When you search for resources, you can filter your search with choices in Grade Level, Price, Subject, Type or Format, and Collections and Conference Materials. You can save your finds in your “My Library” and make collections to share with others. Let us know when you have a collection to share!

Science Learning in the Early Years: Activities for PreK-2

The Feedback Loop: Using Formative Assessment Data for Science Teaching and Learning

Uncovering Student Ideas in Earth and Environmental Science: 32 New Formative Assessment Probes

Creative Writing in Science: Activities That Inspire

Do you ever feel like your science classes could use a shot of imagination? Boost the creativity quotient by assigning a travel blog about the digestive system, a packing list for the planets, or an interview with an atom. You’ll inspire students to be better writers while you enjoy new strategies to assess their scientific understanding. That’s the idea behind Creative Writing in Science. This classroom resource book featuresactivities that integrate writing with content in life science, Earth and space sciences, and engineering and physical sciences for grades 3–12.

Do you ever feel like your science classes could use a shot of imagination? Boost the creativity quotient by assigning a travel blog about the digestive system, a packing list for the planets, or an interview with an atom. You’ll inspire students to be better writers while you enjoy new strategies to assess their scientific understanding. That’s the idea behind Creative Writing in Science. This classroom resource book featuresactivities that integrate writing with content in life science, Earth and space sciences, and engineering and physical sciences for grades 3–12.

Meaningful class discussions

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-04-29

I’m looking for suggestions on how to have class discussions that are meaningful and help students with our learning goals, especially discussing current events or the results of our investigations. Sometimes it goes off-topic or students don’t listen to one another. —C., Virginia

I’m looking for suggestions on how to have class discussions that are meaningful and help students with our learning goals, especially discussing current events or the results of our investigations. Sometimes it goes off-topic or students don’t listen to one another. —C., Virginia

Being able to discuss issues and ideas in a productive manner is important to the future endeavors of your students. Discussions, whether in small or large groups, can be used to focus and share student thinking in terms of summarizing, questioning, comparing/contrasting, making claims and arguments, brainstorming, decision making, and problem solving.

We may think students should know how to do this. But students may come with misconceptions about discussions. They may be used to the idea that a “discussion” means that the teacher asks questions and they respond. This teacher-led interrogation does not include student-to-student questions or in-depth conversations. Or consider what passes for “discussions” on television, where people shout, interrupt, ridicule, and engage in name-calling and other disrespectful and unproductive behaviors (not behaviors we want to encourage or reinforce in our classrooms!).

You may have realized you have to teach students to work cooperatively, take notes in a style related to the task, write informatively, and read science text. So it follows that students may need to learn how to discuss issues and ideas among themselves. As students mature, their interactions should change and the teacher’s input or level of control should decrease.

Some students may be reluctant to participate because of language issues. Some may feel insecure around their louder or more knowledgeable peers. Some students may have ideas to contribute but need support, encouragement, and feedback to participate.

Does your classroom physically support large-group discussions?

Desks or tables in rows may not be conducive to getting all students involved in peer-to-peer discussions: they can’t see each other’s faces, some students hide behind others so as not to participate, and teachers tend to focus on the students nearest to them. Try arranging the desks in a circle or open-U format. (You may have to practice with students to develop a routine for moving desks or tables efficiently.) Sitting in the circle with the students makes a powerful statement about the ownership of the conversation—the teacher is part of the discussion, not just an emcee or moderator.

Establish classroom norms for discussions. What kinds of behaviors or interactions are acceptable? Model the discussion behaviors you’d like your students to learn: attentive listening, wait time, courtesy, and how to channel enthusiasm or express disagreement positively. Resist the urge to “butt in” when the student says something incorrect or controversial. Ask other students to respond first. A question such as “What do you think?” “Do you have anything to add?” or “What did you conclude from this?” can encourage more students to participate.

Students may already have a page of “sentence starters” in their notebooks for written work. Perhaps a section on non-threatening conversation-starters or -continuers could be added: I’d like to know more about… Could you please repeat that? Why do you think that… Here’s what I think you said… What is your source? Can you give me another example? May I add to that? I agree/disagree with that because… Have you considered… I’m not quite sure what you mean.

Students can practice these behaviors in a Think-Pair-Share activity. Discussing ideas with a partner may help them to identify what they might want to say later in a large group. You could start by giving each student a brief reading on familiar or interesting content, such as a news article or website. In this way the students can focus on the process of discussion rather than the acquisition of information.

As students converse, whether in small groups or whole-class, observe what others are doing. Are they interested? Trying to get a word in? Left out?

Recognize that small-group discussions can be very spirited. Don’t worry about the noise level until and unless it gets to be a distraction or a disruption. Often teachers and students select an agreed-upon signal to tone down the noise level or stop the conversations to regroup as a class (e.g., flick the classroom lights, clap their hands, a small bell).

The November 2014 issue of Educational Leadership has articles related to talking and listening in the classroom. Several are available online without a subscription:

Explicitly Speaking, a recent article in Science and Children promotes scientific language and communications through awareness, modeling, supported practice, and integration.

I’m looking for suggestions on how to have class discussions that are meaningful and help students with our learning goals, especially discussing current events or the results of our investigations. Sometimes it goes off-topic or students don’t listen to one another. —C., Virginia

I’m looking for suggestions on how to have class discussions that are meaningful and help students with our learning goals, especially discussing current events or the results of our investigations. Sometimes it goes off-topic or students don’t listen to one another. —C., Virginia