Feature

A Tale of Two Partnership Models

Enhancing Science Learning for Young Children

Connected Science Learning January–March 2020 (Volume 2, Issue 1)

By Jenny Ingber, Jacqueline Horgan, and Veena Vasudevan

Engaging in science at an early age cultivates foundational mindsets and practices for future learning, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and curiosity (Hadani and Rood 2018; McClure et al. 2017). Science learning can be robust for young children when it occurs in a variety of settings (i.e., at home, at school, etc.) and with the support of significant figures in their lives such as teachers, parents, and other family members. In addition to parents and families collaborating in both home and school environments, out-of-school settings offer science learning opportunities that have been shown to promote students’ interest and motivation in science and their science capital. Science capital refers to the multiple dimensions of a learner’s knowledge about and attitude toward science that influences his/her identity and participation in science (DeWitt, Archer, and Mau 2016; Rennie 2017). Informal institutions, such as museums, are uniquely positioned to act as partners in supporting early childhood science learning.

Relationships that exist between science museums and Head Starts (government-funded early childhood education programs for children from low-income families, ages 0–5) have been shown to nurture young children’s natural tendency to explore the world around them, ask questions, make predictions, and develop scientific ideas (Kortenaar et al. 2017). For example, the article “Itty Bitty Science” (Kortenaar et al. 2017) highlights how six museums in the Collaborative for Early Science Learning partner with local Head Starts to develop early childhood teacher capacity and family engagement in science. With cities across the country continuing to design programs to provide universal access to prekindergarten and exposure to early science learning, now is the time to build and expand our understanding of relationships between science museums and early childhood education programs.

This article outlines two partnership models—and their benefits and challenges—between the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and prekindergarten providers on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The partnerships, founded on the idea that children learn across settings and time and are more successful when significant adults in their lives are involved, included professional learning for teachers and opportunities for family engagement, both at school and the museum. The term partnership is used, as all parties involved collaborated on developing a shared understanding of what quality early childhood science learning looks like and how it can be facilitated. During the 2017–2018 academic year, a postdoctoral researcher engaged in a qualitative research study to better understand the nature of the partnerships. Through an analysis of observations, as well as semistructured interviews and focus groups with both teachers and parents, it was found that by leveraging the knowledge and experiences of key stakeholders (administrators, educators, families, and children) and the assets of the museum, different partnership models can each support young children’s access to quality science learning.

Establishing partnerships

In 2016, 100kin10, an organization committed to recruiting, retaining, and supporting STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) teachers, put out a challenge: How should we support teachers to create active STEM learning environments for young students across the country (2019)? (For lessons learned by the museum and others who rose to the 100kin10 challenge, click here.) By responding to this challenge and becoming part of a cohort of educators exploring strategies for addressing the challenge, AMNH had the opportunity to continue to foster current relationships with partners, build new ones, and explore models for expanding access to high-quality science learning for young children.

This new opportunity was essential for AMNH, as the institution is continually seeking to expand its work and enhance the overall quality of early science learning in schools within its community. In 2014 New York City initiated PreK for All and then launched 3-K in a small number of schools in high-need communities during the 2017–2018 school year, with an intention to expand across the city by fall 2020 (NYC DOE 2019a). This also meant it was time for AMNH to ask questions about who best and how to partner with local schools to align with the city’s initiatives. Would direct work with families be the best approach to support children’s learning? Would it be better to work with a greater number of teachers to enhance their science practices and parent engagement in early learning classrooms? Is there some balance between the two? And what are the implications of trying to have a broad reach by leveraging teachers in comparison to deep, immersive, and long-term direct engagement with families?

For over 20 years, AMNH has maintained an ongoing partnership with the Goddard Riverside Head Start. The model for this relationship focused heavily on family immersion, with opportunities for teacher learning intermittently provided throughout the year. In addition to allowing the museum to more deeply understand the partnership model with Goddard Riverside, 100kin10 also let AMNH develop new relationships with Bloomingdale Family Program, a community-based organization offering day care and Head Start for families, and two New York City public schools with universal prekindergarten for four-year-olds, P.S. 84 Lillian Weber School of The Arts and P.S. 111 Adolph S. Ochs. Models for these new partnerships focused more heavily on teacher professional learning, with a few opportunities for family engagement. Centering this model on professional learning allowed the museum to work with a larger number of classes and, in turn, children and families because the teachers were the main point of contact. Even though two models were enacted, one with the Goddard Riverside Head Start community, and one with families and staff from Bloomingdale Family Program, P.S. 84, and P.S. 111—emphasizing either direct work with children and parents or professional learning for teachers—each had similar features:

- A partnership launch meeting and reconvening reflection meeting with administrators from all of the partner institutions

- A family fun night for children and parents from each partner institution

- Class visits to the museum for children, with each child accompanied by a parent or grown-up, and their teachers

- Professional learning for prekindergarten teachers

For both models, class visits to the museum involved the same five learning experiences for teachers, children, and an adult from each child’s family:

- Introduction rug meeting: Museum educators gathered children and their parents for a “rug meeting” conversation that connected the topic of the day to children’s prior knowledge.

- Hall visit (called “expedition” during class): The class explored a museum hall to make observations; compare objects, organisms, or environments seen; and make connections using the observations to gain new understanding of the science topic of the day.

- Reflection rug meeting: Children and parents talked about their observations and experiences in the halls and discussed new ideas, connections, and terminology.

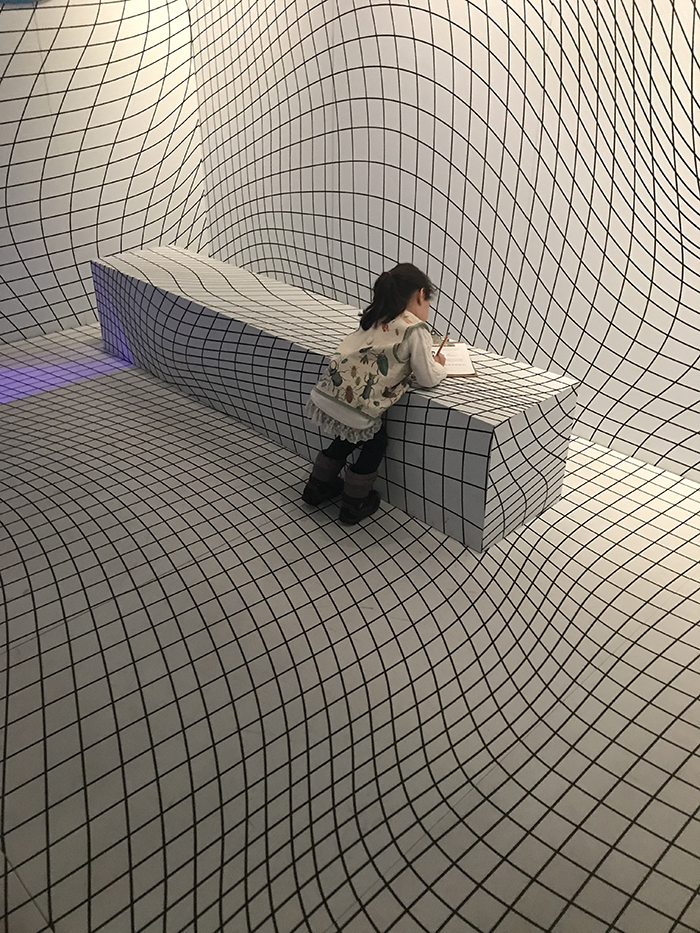

- Free exploration: Children explored the museum classroom with their parents, playing games, completing science puzzles, making science-related art, or observing live animals. Each of these was related to the topic of the lesson.

- Feature creature: A museum educator with expertise handling live animals introduced an animal to demonstrate a phenomenon relating to the topic of the day. Children and parents often handled the animal themselves and had a chance to ask questions and observe features or characteristics of the animal that further supported their learning.

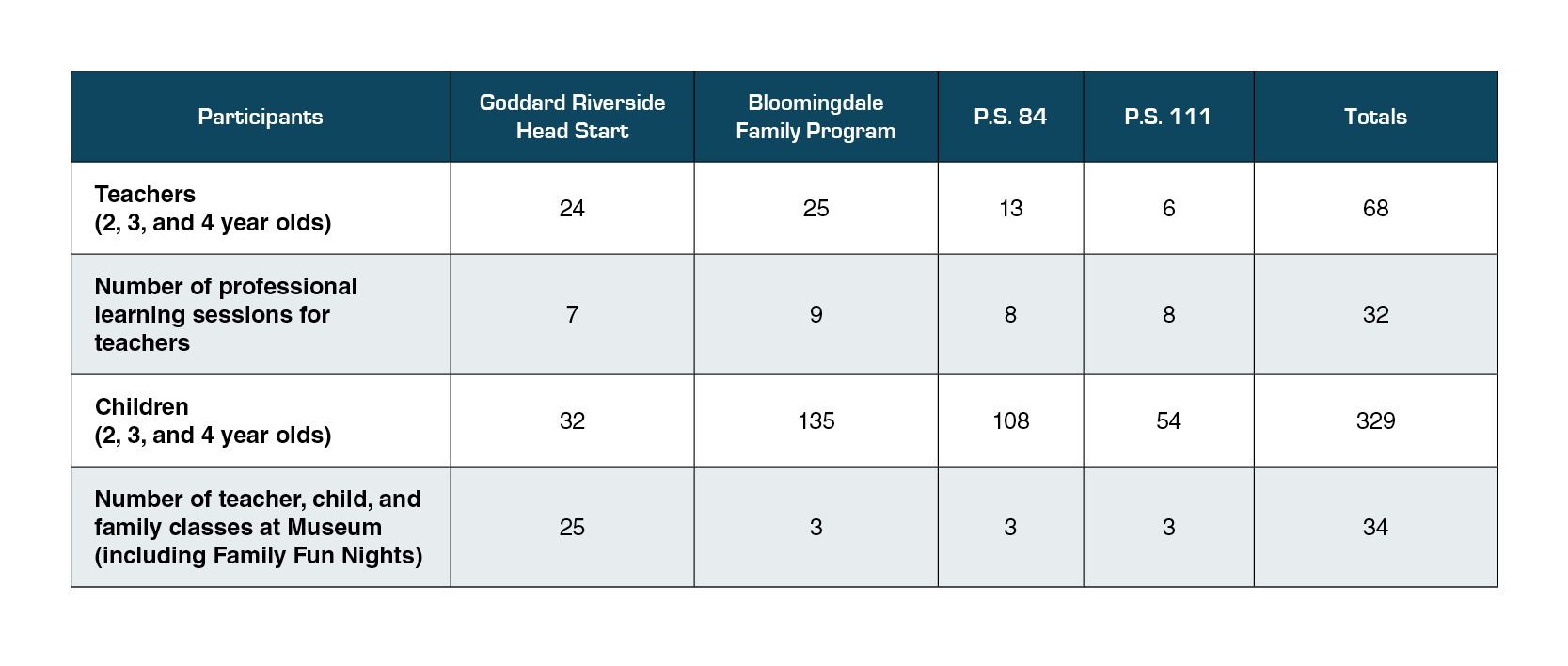

Establishing partnerships with institutions rather than holding professional learning experiences at the museum for self-selecting teachers meant that multiple stakeholders in young children’s lives could participate in the museum’s initiative. Administrators informed the professional learning design by explaining the context, educational philosophies, and goals of their respective schools, and assisted the museum in identifying priorities and understanding when teachers would be available for professional learning. They also provided an understanding of the landscape for learning and children’s access to prekindergarten in New York City, supported teachers’ participation in and implementation of work from the initiative, and encouraged parent participation when appropriate. Teachers participated in professional learning, tested new ideas in their classrooms, collaborated on lesson planning for children’s learning experiences at the museum, and provided ongoing feedback that shaped all of the work of the initiative. Parents and caregivers were also key stakeholders, as they attended orientations about the initiative, participated in class visits (every child was expected to bring a significant adult), attended Family Fun Nights with their children, and provided feedback when asked. The primary stakeholders were the young children who played their role by coming to school and to the museum to learn science. Table 1 provides total numbers of participants and learning opportunities for teachers, children, and families. It should be noted that administrators were invited to and often presented at professional learning sessions and museum visits.

Table 1

Participants in the prekindergarten partnerships

Leveraging museum resources

Essential to the design of each of the partnership models was the use of resources available at the museum. Because AMNH is a natural history museum, dioramas, collections of specimens and objects, and special exhibitions hold the greatest potential for rich science learning among teachers, young children, and families. Dioramas depict science phenomena from around the world that can be observed by young children who might never have been outside of New York City. Museum collections provide novel specimens and objects for observation and data collection, allowing learners to identify patterns in nature or engage in analysis and interpretation to determine, for example, how organisms are similar to or different from one another. Although children at this age are not yet formally held to the expectations established by the Next Generation Science Standards, their experiences in the museum can complement learning in prekindergarten classes and establish foundational understandings of science concepts, all while engaging children in science practices. Young children learn through exploration, play, and interactions with one another and adults within these museum spaces and with museum resources.

Two partnership models

Model 1: Weekly class visits for children alongside significant adults (partnership between AMNH and Goddard Riverside Head Start)

Central to this model were 25 classes implemented from October through May for children alongside their parents/caregivers and teachers. These classes were held at the museum and were complemented with monthly professional learning experiences for teachers, a Family Fun Night in the fall, and a graduation ceremony at the end of the school year in June. Classes each week were intended to align with the school curriculum being taught at Goddard Riverside Head Start, so teachers could support connection-making between learning at school and at the museum. This connection-making was the focus of the teacher professional learning experiences, and was supported by discussions about teachers’ observations of students, parents, and museum educators at AMNH, as well as implications for their classrooms at school. Teachers were asked, explicitly, to share how experiences at the museum lent themselves to learning at school and vice versa. For example, teachers used toy dinosaurs with children in their classrooms to assess children’s takeaways from museum lessons on dinosaurs, birds, and reptiles—particularly examining their ability to observe and compare animals. The Family Fun Night and graduation were community events to further build relationships with stakeholders, especially parents, in a social and celebratory environment.

Having 25 class visits meant that the classes from Goddard Riverside Head Start were essentially participating in a yearlong course of learning at the museum. They studied a range of concepts from the biological and Earth sciences to anthropology. Where possible, museum educators worked with the Goddard Riverside Head Start teachers and the school’s scope and sequence for curricula to ensure that the learning in the museum aligned with learning at school.

Family engagement example: M is for Moon

On Wednesday mornings for two hours per week during the school year, three- and four-year-old children from Goddard Riverside Head Start attended classes at the museum with their teachers and a parent (or another adult from their family). During one particular week, children and their parents learned about the Earth’s Moon. They began their class in front of images of the Moon in the Rose Center for Earth and Space, the museum hall dedicated to astronomy and astrophysics. Children and parents sat in a circle (“introduction rug meeting”) looking at the images and compared Earth to the Earth’s Moon. They were asked, “Who has visited the Moon?” and “What tools would you need to get there?” One little boy stood up and re-enacted the process of taking a rocket to the Moon, putting on a space suit, and then walking on the Moon to demonstrate his ideas about what it takes to travel to the Moon.

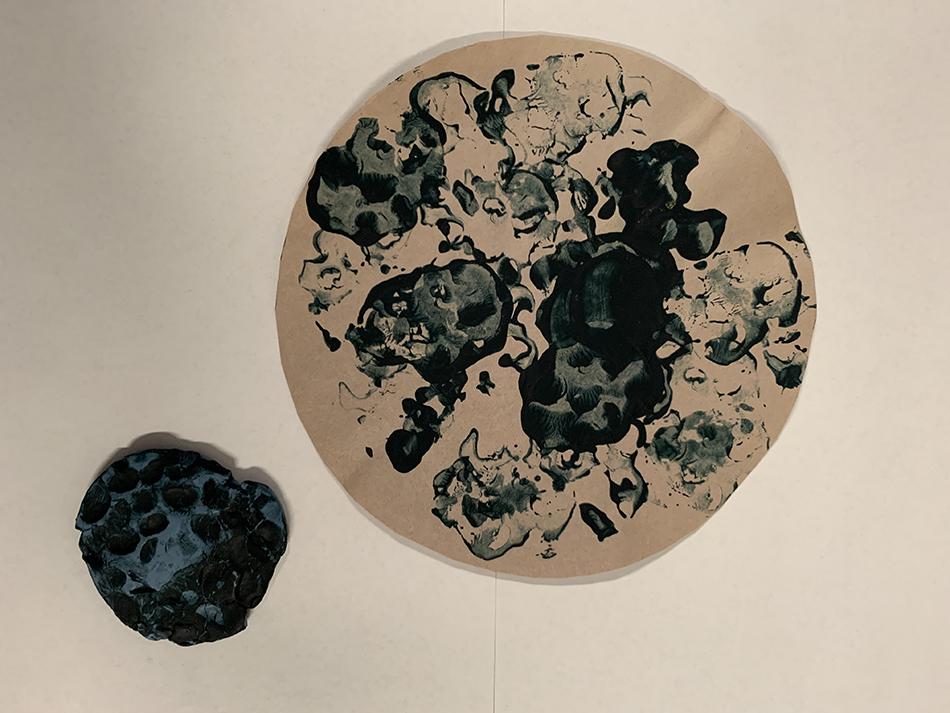

After this discussion, children and parents looked at the photographs in the hall that represent the surface of the Moon and missions to the Moon (“hall visit”). They also touched a model of the Moon in the hall and observed the craters that covered the surface. Learners discussed what they noticed and shared what they thought it would be like to explore the Moon. One of the photographs in the hall is of an item an astronaut left on the Moon during an expedition. Children and their parents were asked to think about and share what they would leave behind on the Moon if they were to visit. Children’s ideas included a teddy bear and a toy car, and a parent said a family photograph was an item they would leave behind. Learners ended their expedition and walked to a museum classroom, where they found tables set up to allow them to explore more information and objects related to the Moon and space travel (e.g., books, astronaut figurines, a sensory table with kinetic sand, puzzles with celestial objects). There were also tables set up for science-related artwork (“free exploration”). The science-related artwork in this case involved children working with their parents to create “craters” by pushing rocks into clay. They then let the clay harden and painted over it to use the clay as a stamp to paint a Moon (i.e., on circular construction paper) with craters in it. This art supported children’s understanding of how craters on the Moon are formed.

Next, children and parents came to the rug (“reflection rug meeting”) and observed another Moon model. This model lit up in different ways to show the phases of the Moon. They heard a story about a little girl who wanted to visit the Moon and were asked again, “What is involved in traveling to the Moon?” and “Why do people want to go there?” Children and their parents discussed the questions with each other and then shared with the whole group.

Finally, a “feature creature teacher” came into the room with a gecko (“feature creature”) and shared a video of geckos in space (New Scientist 2015). Children and parents got to observe and touch the gecko. They discussed with the feature creature teacher what they noticed about the gecko on Earth and the geckos in space. Then they talked about the differences between humans and geckos while revisiting what each needs to survive in space or on the Moon.

Benefits

Holding 25 class sessions with the same group of children at the museum has several benefits. Children and their families became part of the museum community and science becomes a natural and consistent part of their learning experiences. One parent explained, “We enjoy it … We’re learning along with [our children]. We’re grown-ups, but we’re learning these things along with [them] as well.” Through continued engagement in science at the museum, both parents and children grew as science learners and were able to nurture the unique bond they have in a new way.

Teachers engaged in this model also expressed that they grew as science learners, specifically in their developed ideas about science. One educator expressed, “Now we know that science is all around us,” noting that prior to her observations at the museum, her understanding of science was more associated with textbooks, scripted labs, and memorization.

A shared understanding of science (fostered through parent, teacher, and child participation in the partnership) means that children will be supported in making science connections across home, museum, and school settings, and are more likely to engage in high-quality science learning experiences.

Challenges

The reach of this model is limited, as only 32 child/parent pairs participate per year. Additionally, although many parents were able to participate in all 25 lessons, some were unable to attend weekly classes with their child, due to work conflicts or the need to be with other children at home.

Inconsistent communication about what children are learning at school or additional academic, personal, or linguistic needs could present challenges to the overall design of the learning experiences for the families. Close collaboration with and consistent communication between teachers and museum educators are essential for weekly classes to be relevant to the children and aligned with the school curriculum.

Model 2: Professional learning for early childhood teachers (partnership between AMNH and Bloomingdale Family Program, P. S. 84, and P. S. 111)

Over the course of an academic year, and for a total of about 24 hours, early childhood teachers participated in a variety of professional learning activities inspired by the Science Immersion Model for Professional Learning (SIMPL) (Lauffer 2010). This model engages teachers by positioning them as learners of science and by giving them opportunities to reflect on science learning, both for themselves and for their students. All teachers participated in two learning cycles—one during the fall and one during the spring—which provided teachers opportunities to:

- learn science at the museum and at their school sites;

- collaborate with museum educators to inform the design of museum learning experiences for their students;

- observe their students learning, alongside significant adults, at the museum during class visits; and

- reflect on science learning that happened at the museum during each cycle and across the year.

Families from Bloomingdale Family Program, P. S. 84, and P. S. 111 participated in two class visits to the museum (one per cycle) and a Family Fun Night during the spring.

Professional learning example: Senses

The fall cycle was designed using the theme “senses.” Each of the three institutions participating in the initiative began their prekindergartners’ year with a curriculum unit that involved the children in learning about themselves and how they can use their senses to explore the world around them. For example, in New York City’s Department of Education PreK for All Interdisciplinary Units of Study, the second unit of the year is called “My Five Senses” (NYC DOE 2019b). Simultaneously, when the museum began this initiative, it was hosting a special exhibition, Our Senses: An Immersive Experience, so the theme seemed to be ideal for the fall cycle.

For the first professional learning experience about senses, teachers explored their own senses through a variety of activities, such as smelling different scents and walking along a line to identify “balance” (e.g., equilibiroception) as a sense they may not have previously considered. Teachers explained that through the activities, they expanded their understanding of their senses beyond taste, touch, smell, hearing, and seeing to include a wider array of human senses such as balance and feeling changes in temperature. Next, teachers went to visit the Discovery Room in the museum to have a multisensory science learning experience. There, they observed different live animals, compared objects such as rocks and human artifacts, and excavated a dig pit to uncover dinosaur fossils. Teachers reflected on their learning experiences and discussed implications related to how they learned science in the past and strategies for teaching the young children in their classes.

After the teachers’ first professional learning session at the museum, the conversation around senses continued at their school sites during one- to one-and-a-half–hour sessions with their colleagues and a museum educator. At each session, teachers engaged in science learning related to senses, reflected on content and practice, and discussed implications for their students’ learning.

The next professional learning experience about senses held at the museum was three hours. During this visit, teachers

- engaged in a science learning experience that began with a meeting about senses;

- explored (with the use of an expedition worksheet) a special exhibition, Our Senses: An Immersive Experience, which highlighted different human and animal senses and perceptions; and

- discussed what they noticed and learned from their time in the exhibit.

After engaging in science as students, teachers reflected on the experience and had a whole-group conversation guided by the following prompts:

- Before: How did you feel the experience was set up? What other questions could you ask your students to elicit prior knowledge, predictions, or questions? What is the purpose of eliciting students’ previous knowledge, predictions, or questions prior to engaging in an activity, such as visiting a museum exhibit?

- During: In the exhibit, why was the expedition sheet created the way that it was? How did the expedition sheet support learning? What challenges did it create? How do you foresee children completing this and moving through the exhibit? What will the facilitator moves, or teacher behaviors, be? What will the parent engagement expectations be?

- After: How can you debrief the experience with children? What connections can be made between home and school?

This conversation was used to develop a learning experience for children and parents for their visit to the museum. Two sites chose to bring their classes to Our Senses: An Immersive Experience, whereas the other site opted to visit the Butterflies exhibit. All educators discussed the strategies they could implement to prepare students and their parents for the visit, connect the exhibits to content and practices relevant to each class, and facilitate reflection activities and discussions back at school. Teacher collaboration with one another and with the museum educator was a hallmark of the partnership and enhanced the professional growth of the participants as they learned together. Through these experiences, teachers explained that they became more cognizant of science in their classroom and began integrating new practices to facilitate quality science learning for their students.

Benefits

In this model, nearly 300 children and their families were impacted by their school’s partnership with the museum. Families attended Family Fun Nights and children joined their parents and teachers for two class visits each (once in the fall and once in the spring). Several teachers pointed out the changes they noticed in their children’s interactions with their parents after engaging in science experiences at the museum. One teacher explained, “Going to the museum and seeing the exhibits gave [parents] good ideas … sometimes parents don’t really know how to integrate science into everyday … [but now] the parents have been taking the conversation and taking it home.”

Teachers’ perceptions of science were also influenced by their experiences at the museum. They expressed that they came to feel like science is important to do and learn, which by virtue helped their students to view science more positively. The immersive and yearlong professional learning experiences were critical in supporting teachers’ classroom practices. One teacher noted that the professional learning helped her think through challenges within her preK environment, such as how to design a high-quality science center and how to integrate science into other subjects.

Access, in terms of the number of children and the quality of science learning, increased for young children, as both their parents and teachers developed ideas for how to facilitate in meaningful ways science discussions and experiences for their students.

Challenges

Depending upon the partner school, scheduling time with teachers and transportation for children and their families presented some challenges. There are many competing priorities for early childhood teachers, as they are responsible for the care and learning of young children all day—and in the case of Head Start and community-based organizations, all year. Early childhood teachers’ time for professional learning is limited, which made this partnership special, but also made it difficult to schedule. Another challenge was ensuring that the needs of each teacher within the large group was met, as the levels of teaching experience and affinity for science teaching and learning were varied among them. This partnership model is still evolving to appropriately differentiate and meet the needs of each individual teacher.

Conclusions and next steps

Each of the two partnership models between preK providers and AMNH supported young children’s access to high-quality science learning (see full evaluation report). The approach of providing weekly class visits for children alongside significant adults (parents and teachers) established a science learning community among families, teachers, and the museum, in which all participants developed a shared understanding of and comfort with science. This outcome is consistent with findings from other partnerships between cultural institutions and early childhood providers. For example, the St. Louis Science Center, a participant in the Collaborative for Early Science Learning noticed that when parents were engaged in consistent family experiences at the museum, adult learning partners felt more comfortable with science and developed an understanding of how they can integrate science into their children’s lives at home (Kortenaar et al. 2017). Additionally, weekly visits allowed for greater connections between children’s science experiences at school and their learning at the museum. There is greater potential in this model, however, to support teachers in applying new ideas about science, based on their museum observations, in their school classrooms. Doing this would require teachers to examine the ways in which the science themes and experiences from the museum can be integrated with or connected to other disciplinary learning in the classroom. For example, teachers could further infuse classrooms with the science learned at the museum by selectively including books for classroom reading, materials for dramatic play, or manipulatives that foster the re-creation of museum experiences or sense-making of science ideas.

The professional learning for early childhood teachers model resulted in more observed teacher changes in their classrooms at school, specifically in their approaches to their science centers and integrating science into other subjects. This is similar to the shifts in teacher behavior noticed in a partnership between the Bay Area Discovery Museum (BADM) and local Head Starts, through a program called Connections (Kortenaar et al. 2017). Teachers involved in the partnership with AMNH and with BADM made changes in their science centers that focused more on scientific practices and skills, rather than science content alone. Families from the AMNH partnership were exposed to positive science learning experiences but could benefit from more engagement to feel more closely connected to a science learning community. Firsthand experiences with scientists and other professionals in science fields could make science feel more accessible and exciting for families, especially those who may not have ever met individuals working in the field. Additionally, opportunities for families to do science themselves alongside experts could bolster parents’ understanding of science practice and their likelihood of seeing science as a context for them to explore and ask questions together.

Partnerships between informal science institutions and prekindergarten providers can support the enhancement of science learning among early childhood teachers as well as young children and their families. Cultural institutions or early childhood providers interested in establishing partnerships should consider engaging children, families, and teachers by providing several touch points throughout the year for all participants. Additionally, it is important to prepare for challenges that arise and collaborate with all stakeholders, including administration, to understand the needs of the partnership and appropriately respond.

AMNH continues to sustain two models of partnership, each with benefits and challenges, in an effort to support high-quality early science learning in New York City. In the continued phases of partnership, the museum and its partners are dedicated to better understanding appropriate models for different contexts, and how to design programming for children, families, and teachers that is culturally responsive and relevant. As New York City and cities around the country offer universal access to prekindergarten, more opportunities for developing similar partnerships should be considered.

Jenny Ingber (jingber@amnh.org) is the director of children and family learning at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, New York. Jacqueline Horgan (jhorgan@amnh.org) is a senior coordinator in the Science and Nature Program at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, New York. Veena Vasudevan (veena.vasudevan@gmail.com) is a postdoctoral associate at New York University Steinhardt School of Education in New York, New York.

citation: Ingber, J., J. Horgan, and V. Vasudevan. 2020. A tale of two partnership models: Enhancing science learning for young children. Connected Science Learning 2 (1). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-january-march-2020/tale-two-partnership