Focusing on Instruction to Improve My School

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-09-25

How do you envision science education in your classroom? Your school? Your district? In hectic life of a modern educator, it is easy to become overwhelmed by the initiatives, expectations, and pressures of our profession. As a first-year high school administrator, I admit I experienced a point last year when I was simply surviving—not managing adequately, but just barely managing.

Fortunately, I was assigned a leadership coach who recognized the signs of an impending collapse. He advised me to re-center myself by focusing on the one thing that would make the biggest difference in my school and ensuring that one thing was done well and consistently. He told me if I could devote time each day to that one thing—regardless of whatever else I might face—I would know I had made a difference.

Fortunately, I was assigned a leadership coach who recognized the signs of an impending collapse. He advised me to re-center myself by focusing on the one thing that would make the biggest difference in my school and ensuring that one thing was done well and consistently. He told me if I could devote time each day to that one thing—regardless of whatever else I might face—I would know I had made a difference.

The kicker is that this “one thing” had to include something tangible, some evidence to show I was working toward my “one thing.” The one thing I chose was instruction. I want the students in my school to have the highest degree of quality instruction, consistently delivered to them. For this to happen, I had to leave my office and visit classrooms and converse with teachers about instruction. The observations I made, the feedback I gave, and the discussions I had regarding what quality instruction is, what it looks like in a particular grade level and subject, and how we could make it happen consistently, provided clear evidence that I was focusing on my “one thing.”

I want teachers in my building to have this same singular focus. The “one thing” I want them to concentrate on is teaching well every day. I want them to devote time and energy to designing challenging, engaging lessons that push their students to grow in their knowledge and understanding. I want them to start each day by reflecting on what their vision for education looks like in their classroom, and if they teach science, I want them to consider the vision set forth by the Framework for K–12 Science Education, and make that vision a reality.

While I would love to stand and say this to my faculty, I know my words would be received with skepticism at best. The truth is that we live and work in a state that still requires high-stakes assessments. The scores of those assessments are used to evaluate teachers, administrators, and schools. Those assessments aren’t perfect; everyone agrees they don’t provide a full picture of a student’s growth over a year; and they aren’t going away. So I can’t tell my teachers they don’t matter, because they do. What I can say is that how we define assessment in our school can change, and that the traditional summative end-of-year assessment isn’t the “one thing” on which we should solely focus.

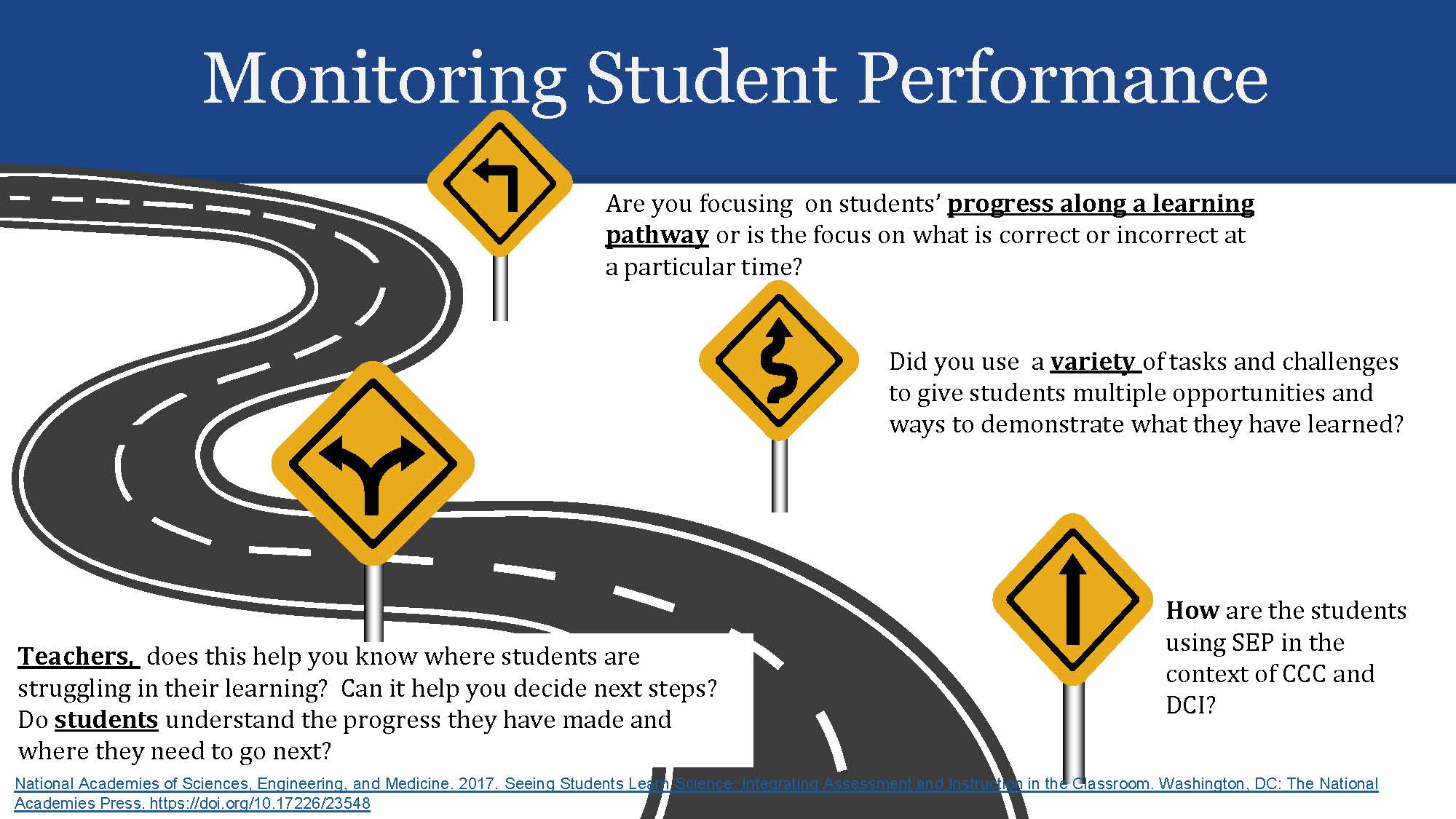

This summer, I studied the recently published National Academies Press report, Seeing Students Learn Science: Integrating Instruction and Assessment. One key idea that really resonated with me is that assessment should be an integrated part of classroom instruction and not an interruption or sole event. This shift in perspective has helped me better reframe this discussion on instruction and assessment and what they should look like at my school. To accomplish this, I have restructured key ideas presented in the book to create questions that teachers can ask themselves and that I can ask during our conversations about teaching and learning. (see slide)

I would like to report that this second year has begun flawlessly and that we are consistently having rich discussions about integrating assessment into instruction. The truth is, after just more than a month into the school year, we are still taking baby steps. My teachers are still trying to grasp how to change their instruction and assessment practices, and I am still learning how to be an administrator. What we do have is a focus, a “one thing” that we believe matters most, and a belief that the little changes we make each day to accomplish that one thing will eventually result in an experience that matches the vision we have for our classrooms, our school, and our district.

Zoe Evans

Zoe Evans is principal of Bowdon High School in Bowdon, Georgia. Before becoming an administrator in 2012, she taught middle level science for 19 years in Florida and Georgia. Evans is a National Board Certified–teacher in Early Adolescent Science and a Georgia Master Teacher. She is the 2005 Georgia recipient of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching.

Evans served on the writing team for the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and has collaborated on many projects, including the NGSS EQuIP Professional Learning Facilitator’s Guide, NGSS Example Bundles, and NGSS Evidence Statements. She also is an EQuIP Rubric trainer, NGSS@NSTA Curator, and NSTA’s District V Director. Evans earned a bachelor’s degree in middle grades education, a master’s degree in middle grades science, and a specialist’s degree in middle grade science from the University of West Georgia.

This article was featured in the September issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

Administration Teaching Strategies