Research and Teaching

A Journey to Acceptance

A Study of Biology Majors’ Attitudes Toward Evolution Throughout Their University Coursework

Journal of College Science Teaching—September/October 2020 (Volume 50, Issue 1)

By Chad Talbot, Zeegan George, and T. Heath Ogden

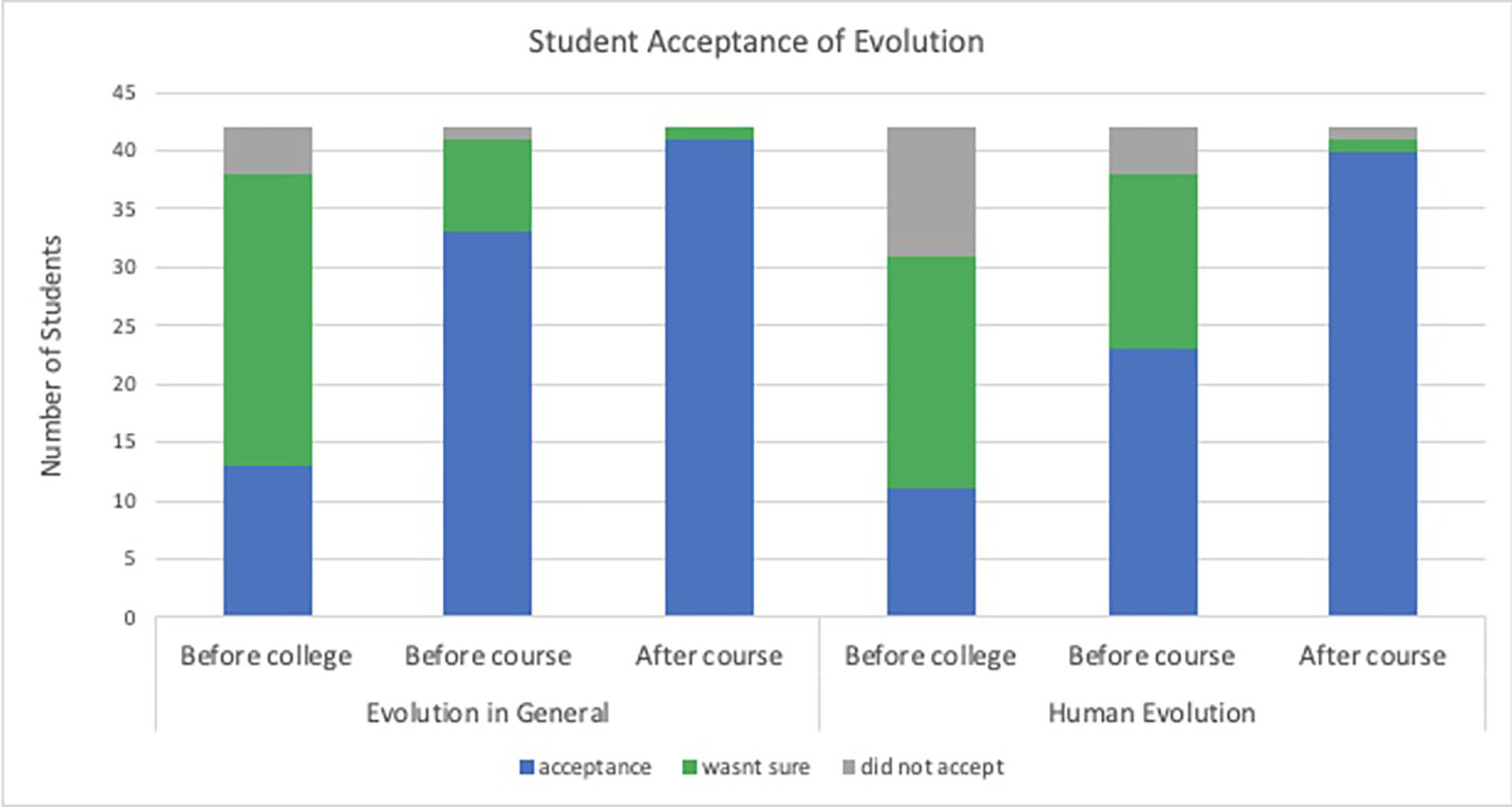

The main objective of this study was to characterize the acceptance of evolution among biology majors. Semi-structured interviews were carried out to track the opinions of students in relation to two aspects of evolution: (1) attitudes toward evolution in general and (2) attitudes toward human evolution. The participants characterized their acceptance of evolution for three distinct times during their university coursework; (1) at the beginning of their degree (before attending the university), (2) at the beginning of the capstone evolution course, and (3) at the end of the evolution course. Their acceptance of evolution in general changed from 31% to 79% to 98%, respectively, and their acceptance of human evolution changed from 26% to 55% to 95.2% respectively. This study investigated some of the factors that influence acceptance, such as an increased knowledge of the evidences, a religious scientist role model, and a reconciliation of scientific and religious worldviews. The results indicate that for biology majors in this study, the accumulated knowledge of the evidences of evolution over the duration of their degrees was the most influential factor.

The theory of evolution is the unifying theme in biology and is central in understanding and teaching biology courses (Carter & Wiles, 2014; Dobzhansky, 1973). The scientific community widely accepts evolution as the best mechanism to explain biodiversity. In spite of this fact, evolution has been, and remains, a controversial subject in society, especially when focusing on human evolution (NSTA, 2013). Studies have frequently shown the disconnect between the scientific community and the general public in regard to acceptance of human evolution, with less than 50% accepting some form of human evolution (Miller, 2008). Although there has been much disagreement and opposition to human evolution, polls have shown a gradual increase in acceptance over the last decade. For example, research from 2014 reported a 62% acceptance (Pew Research Center, 2014). In a more recent poll, that percentage has increased to 68% (Pew Research Center, 2019). In this same study, they also decided to ask the human evolution question differently, essentially giving the respondent three options: (1) acceptance with no higher power intervention; (2) acceptance with higher power intervention; and, (3) rejection of evolution with humans existing in their current form since the beginning of time. When asked in this way, 81% of the respondents choose either of the first two options. This increase clearly is due to the wording of the questions on the survey, highlighting the importance of how questions are posed. Even though acceptance is increasing across the nation, a lack of knowledge about this issue exists and further investigation of this topic is needed to more fully understand why there is a rejection of the idea of evolution and the reasons as to why it is not more accepted.

There have been numerous studies focused on the acceptance of the theory of evolution (Abraham et al., 2012; Cobern, 1994; Dagher & BouJaoude, 1997; Downie & Barron, 2000; Gibson & Hoefnagels, 2015; Hill, 2014; Miller et al., 2006; Nadelson & Southerland, 2010; Nehm, 2006; Nehm & Schonfeld, 2007; Sinatra et al., 2008; Stanger-Hall & Wenner, 2014; among others). Many studies have shown a large disconnect among various people; this may be due to the incongruence between people’s understanding of animal or plant evolution (general) and human evolution. Generally, individuals find it easier to accept animal or plant evolution (general) in comparison to human evolution (Miller et al., 2006; Sinatra et al., 2008).

There are many reasons for the rejection of evolution and they vary in relation to evolution in general and human evolution. For example, many people have difficulty accepting evolution due to misconceptions about the theory itself (Battisti et al., 2010), or a lack of understanding. Others have contradictory worldviews (Cobern, 1994; Dagher & BouJaoude, 1997) or religious beliefs (Coyne, 2012; Hill, 2014; Schilders et al., 2009), and these reasons tend to be more important for those that reject human evolution. Whatever the reasons are, they can be complex, diverse, and are not easily resolved. This highlights the importance that increasing knowledge may not be the primary solution (Abraham et al., 2012; Gibson & Hoefnagels, 2015; Hill, 2014; Nadelson & Southerland, 2010; Nehm, 2006; Nehm & Schonfeld, 2007). The process to accept or reject evolution is not simple; each individual has different experiences, beliefs, and worldviews that are used to make such a choice (Glaze & Goldston, 2015).

This has been found to be true in college students as well, both pertaining to misunderstanding of evolutionary theory (Foster, 2012) and opposition due to beliefs (Stanger-Hall & Wenner, 2014). Contradictions of students’ beliefs with evolutionary theory result in a greater difficulty for students to learn and accept evolution (Cobern, 1994; Dagher & BouJaoude, 1997; Downie & Barron, 2000; Stanger-Hall & Wenner, 2014).

Although there have been many studies done on evolutionary acceptance, there is very little literature reviewing college biology majors’ views of evolution or if their views have changed during their college coursework, and the reasons for those changes. This could be due to the fact that investigators can assume acceptance among biology majors, causing them to be overlooked (Rice et al., 2011). One study focusing on an upper-level evolution course showed students’ understanding and acceptance increased from the beginning to the end of the course (Ingram & Nelson, 2006). Other studies, not focused on biology majors, have shown an increase in acceptance due to effective teaching (Manwaring et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2018). In general, students majoring in the biological sciences have a better understanding of evolutionary theory compared to nonmajors (Abraham et al., 2012; Cotner et al., 2017; O’Brien et al., 2009; Paz-y-Miño & Espinosa, 2009). It would be important to evaluate biology students’ level of acceptance before college, before the senior-level evolution course, and after the course. Furthermore, it would be important to investigate the reasons as to why biology students change their views.

There have been many forms of collecting data on acceptance of evolutionary theory. One of the most common methods for gathering data is through the use of surveys (Carter & Wiles, 2014; Ingram & Nelson, 2006; Manwaring et al., 2015). Another effective method of collecting data is through interviews (Patton, 2005); they produce higher quality responses and higher response rates (Nelson et al., 2003; Owens, 2005). Semi-structured interviews are an important research tool when conducting qualitative research because they elicit more personal responses from the participants and allow for more flexibility (Merriam, 2009). The interview is designed around a predetermined set of questions, but it also allows other questions to come from the dialogue (Whiting, 2008).

This study’s main objective is to understand the acceptance of evolution in biology majors over the course of their degree at a public, open-enrollment institution in a highly religious community. Specifically, the acceptance of evolution in general and acceptance of human evolution will be investigated. This study also intends to elucidate factors that influence the acceptance, or nonacceptance, of evolution in biology majors. We hypothesize that as students, even religious students with low initial acceptance, progress through their biology degree their acceptance of evolution would increase. We focus on three main factors that affect acceptance: (1) an increased knowledge of evolution and the evidences supporting the theory; (2) the influence of a religious scientist role model; (3) the reconciliation of scientific and religious worldviews.

Methods

Demographics

The study included biology majors at a public postsecondary institution in the state of Utah. Utah offers a unique demographic that makes it an interesting location to conduct research on acceptance of evolutionary theory due to its high percentage of religious residents.

Mini-survey and semi-structured interviews

Participants (N = 42) included students from senior-level biology courses Evolution (BIOL 4500) and Molecular Evolution (BIOL 4550). Instructors of these courses were contacted and subsequently gave permission to send an e-mail announcement to all the students in each class. After the instructors finished teaching human evolution (this was during the second half of the semester for all instructors), a sign-up sheet was passed out in class and students provided contact information in order to conduct the interviews. All students that participated in the research were volunteers and received no compensation or extra credit in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB #01782). The interviews were carried out over the course of three semesters.

At the beginning of each interview, an informed consent was given and collected. A short survey of five questions was then introduced to all the participants in order to effectively obtain demographic information to make correlations to students’ views of evolution (see Appendix 1). The short survey was followed by a semi-structured interview of 12 questions to better understand the factors that influenced the acceptance or rejection of evolution and human evolution (see Appendix 1). The questions in the interviews were designed to review the answers students gave in their short survey and provide participants the opportunity to further explain their acceptance or rejection of evolution. All interviews were recorded and then transcribed.

The transcribed student interviews were coded and analyzed to determine any factors, trends, patterns, etc. in relation to the direct responses. Three preliminary categories, based on similar research (Holt et al., 2018), were used to bin data in relation to change of opinion toward evolutionary theory. These categories correspond to three factors that might drive students’ acceptance of evolution: factor (1) evidence of evolution itself influenced acceptance; factor (2) reconciliation of religious beliefs with evolution; and factor (3) the presence of a role model that exemplifies how one can accept evolution and maintain religious belief. It was possible for a student to have multiple factors that influenced their acceptance. Thus, in some cases a student was binned in more than one category.

Data analysis

The responses from all three semesters were compared using a two-proportion z-test. The Cochran’s Q test was used to determine if there was a significant difference between the number of students who changed their beliefs for one reason versus another, as well as the overall statistically significant effect of the course on students’ attitudes. All statistical analyses were performed with alpha set to p < 0.05.

Results

Evolution in general

As students progressed through their biology coursework, they increased in their acceptance of evolution. Before college 31% of students accepted evolution in general, 59.5% were not sure, and 9.5% did not accept; before the course 79% accepted, 19% weren’t sure, 2% did not accept; after the course 98% accepted, 2% were not sure, 0% did not accept. There was a significant (p-value = 0.00000774) increase of 48% in acceptance of evolution in general from before college to before the start of the evolution course (Figure 1). Likewise, there was a significant (p-value = 0.000000121) increase of 67% in acceptance of evolution in general from before college to after the evolutionary course and a significant increase (p-value = 0.00468) from before the course to after the evolutionary course.

Student responses for level of acceptance of evolution at three distinct time periods for both evolution in general and human evolution. Responses were recorded for attitudes before college, before the course, and after the course.

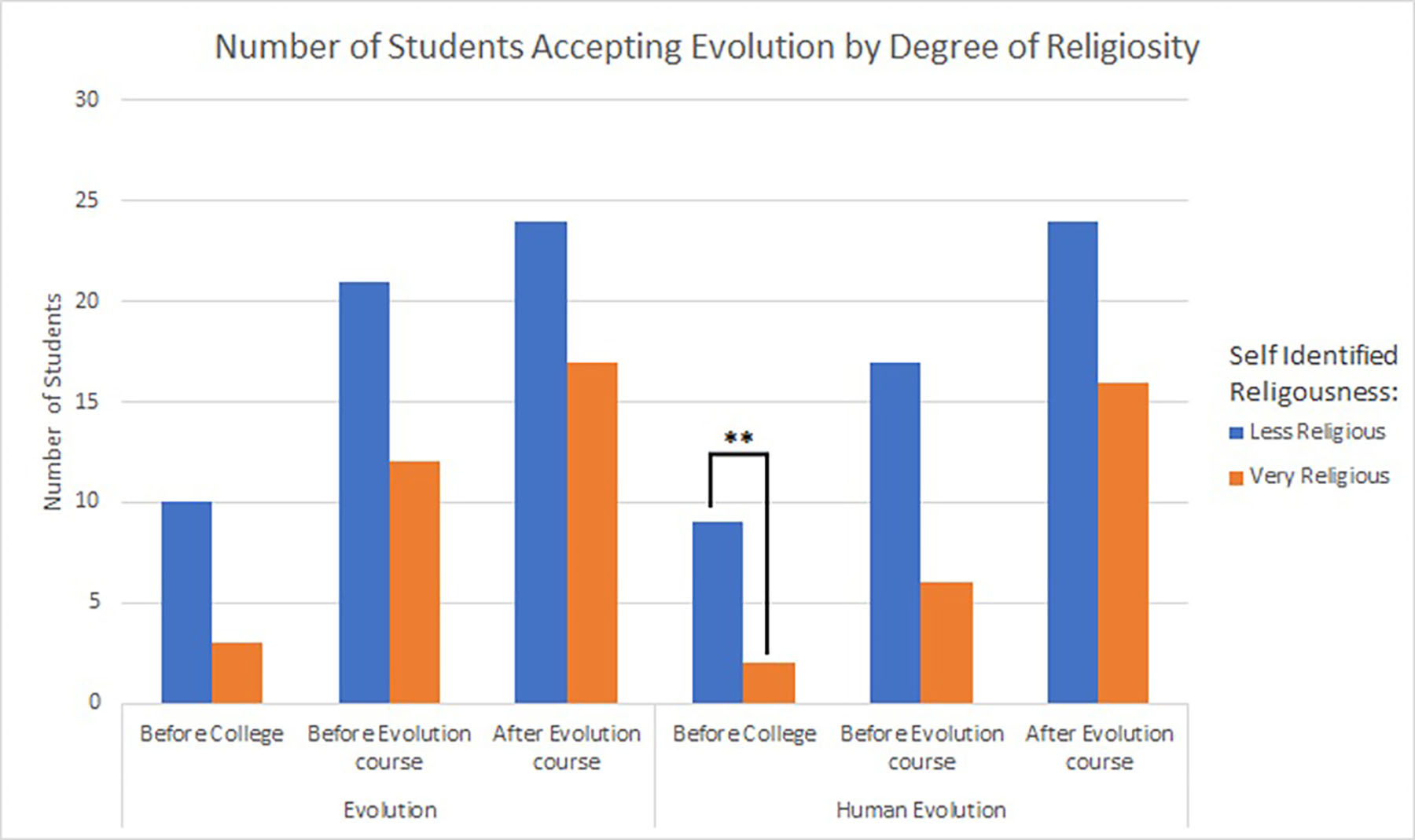

Religious students and nonreligious students showed a difference in their acceptance of evolution in general. Before college, religious students accepted evolution in general 26% of the time compared to nonreligious students with 50% acceptance. Before the course, acceptance of religious students was 76.5% compared to 87.5% for nonreligious students. After the course, religious students’ acceptance was 97% compared to 100% for nonreligious students. All participants with low acceptance were able to increase acceptance over time. In spite of their low acceptance before college (26%), religious students were able to change their views on evolution, and by the end of the senior-level evolution course 97% accepted evolution in general.

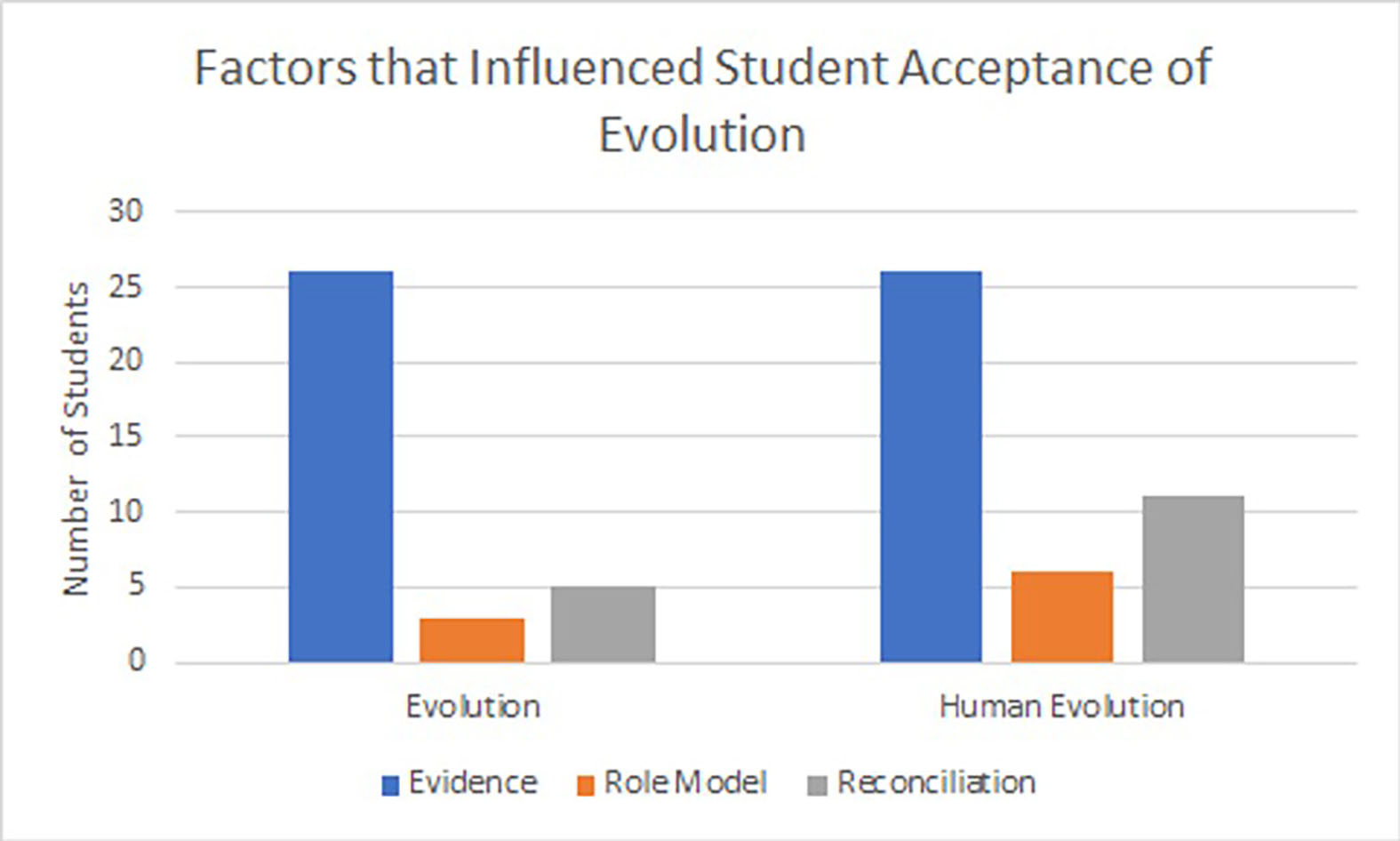

The reasons for changes in attitudes vary among students. The data indicated that 33% had no change at all, 55% changed due to increased knowledge in the evidences of evolution, 12% changed due to reconciling religious beliefs, 7% changed due to an influential role model, and 11.9% of students showed a combination of these factors.

Human evolution

Similar results were seen when looking at acceptance of human evolution. Before college 26% of students accepted, 48% were not sure, and 26% did not accept. Before the course, acceptance increased to 55%, 35.5% were not sure, and 9.5% did not accept. The difference between students’ acceptance before college and before the course was statistically significant (p-value = 0.000532). After the course, the trend continued with 95.2% of students accepting, 2.4% were not sure, and 2.4% did not accept human evolution. The difference before college to after the course (p-value = 0.0000374) and before the course to after the course was statistically significant (p-value = 0.0000000724).

There was a significant difference (p-value = 0.0156) between religious students and nonreligious students when looking at the acceptance of human evolution before college (23.5% acceptance and 37.5%, respectively). Before the course both religious students and nonreligious students increased their acceptance to 50% and 75%, respectively. Finally, after the course 94% of religious students and 100% of nonreligious students accepted human evolution. Religious students were able to increase their acceptance by 70.5% from before beginning college (23.5%) and after completing their evolutionary course (94%).

The reasons for changes in attitudes toward human evolution varied as well. The data indicated 31% of students experienced no change, 43% showed a change due to evidences, 26% changed due to reconciling religious beliefs, 14% changed due to influence of a role model, and 26% had a combination of the aforementioned factors (Figure 2). This shows a stronger connection between acceptance of human evolution and reconciling religious beliefs (26%) versus acceptance of evolution in general and reconciling religious beliefs (12%).

Factors that influence acceptance of evolution and human evolution during students’ college experience. For some students, acceptance was influenced by a combination of factors.

Discussion

Due to the unique study population, consisting of students with highly religious views, there are many things that can be learned and used for future education on evolution, especially in areas where religious belief is prominent. Over 90% of the participants were religious, which has been shown to have a negative correlation with acceptance of evolution. Notwithstanding this correlation, students were able to eventually accept evolution, even human evolution (as detailed below). This study is unique from other studies looking at evolution acceptance because it provides more specific information on how highly religious students majoring in biology deal with their worldview and evolution. It has been assumed that most students in biology may already accept evolution (Rice et al., 2011). Regardless of these assumptions, this study showed that prior to beginning university studies in biology, only 31% accepted evolution in general and increased to nearly 100% by the end of the senior-level course on evolution. A further examination of the three factors that likely influence the acceptance of evolution in this student population is warranted.

Factor #1: Increased knowledge of evolution and the evidences supporting the theory increases acceptance

One of the largest factors we found to influence students’ views of evolution was simply the process of students seeing the evidences for evolution. Many students were not informed about evolution or had misconceptions due to a variety of reasons coming out of high school. Students reported that it was the knowledge of ideas such as natural selection, sexual selection, genetic drift, phylogenetics, the fossil record, homologies, etc. that enabled change in their views on evolution. See factor #1 quotes at for specific examples.

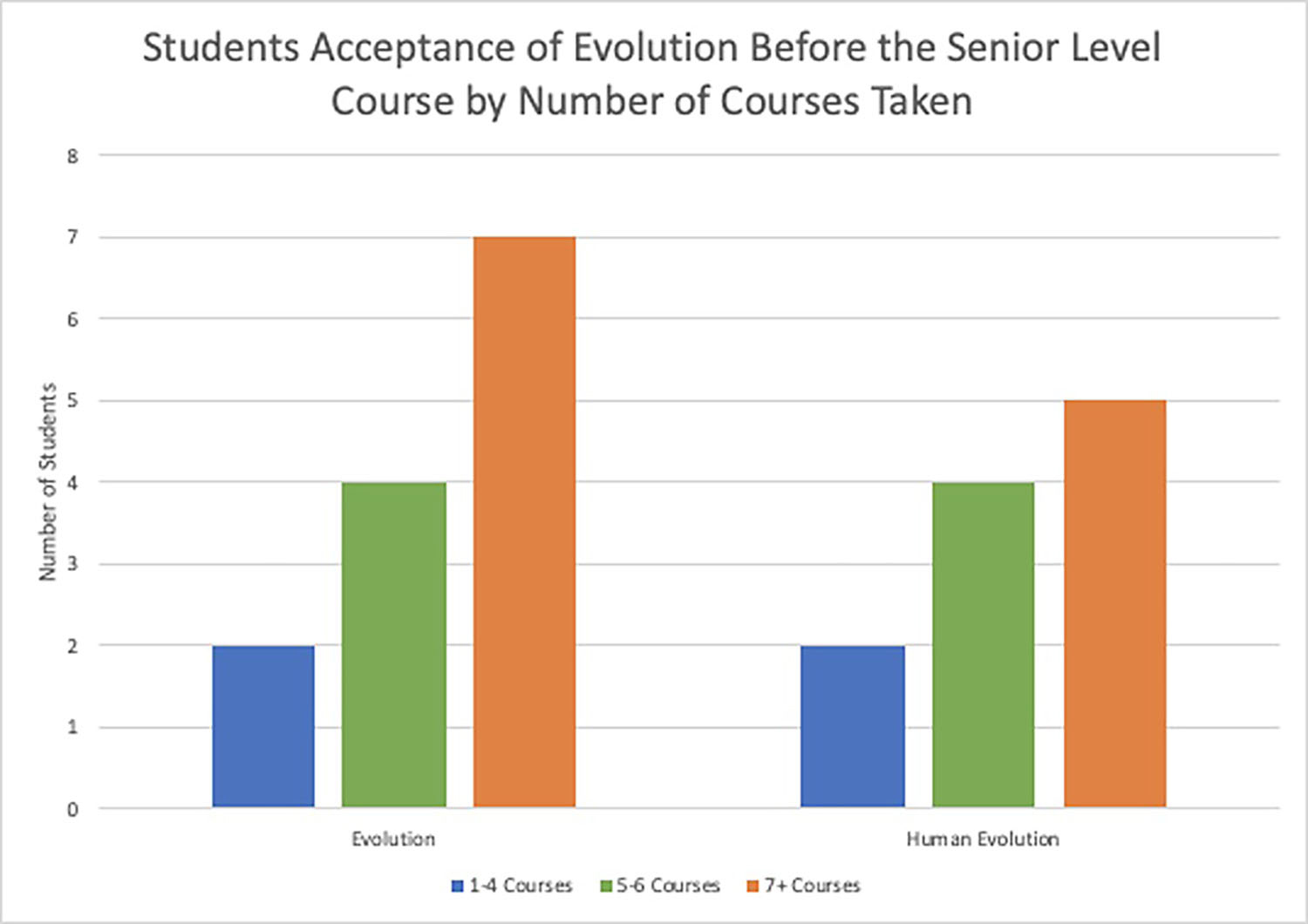

As students began taking introductory biology courses, they were exposed to the concept of evolution early in their careers; however, a detailed course focusing only on evolution typically is taken by students just prior to graduation. When looking at the “before the evolution course” data, there is a trend indicating that the more courses (with an evolution theme) completed by students resulted in a higher rate of acceptance (Figure 3). This applied to both evolution in general and human evolution. This gradual exposure along with a senior-level course allowed students to clarify many possible misconceptions or erroneous assumptions in relation to the theory of evolution.

Student participants’ acceptance of evolution in general and human evolution related to the number of courses that included evolutionary themes taken before the senior level course.

One important intervention that many students reported as being influential, was an activity that involved looking at different hominid skulls and comparing them (see Appendix 2). This activity allows students to see the well-documented transitions from a more chimp-like skull to a more Homo sapien-like skull. Taking the time to let students see and feel for themselves the fossil record seems to be much more effective than just talking about it or having them read about it.

Many students expressed that they did not understand the theory before taking courses associated with evolution. This led to misconceptions about the theory itself. As soon as students were able to see for themselves the information supporting evolution, they found it “hard to deny the facts,” “hard to refute,” and “I don’t know how anyone could ever doubt it” (see Appendix 2).

Factor #2: The influence of a religious scientist role model increases acceptance

An additional factor that was apparent after completion of the interviews and has been demonstrated in previous studies (Holt et al., 2018), is the influence of a religious scientist role model. The participant responses (Appendix 2) indicate that the influence of a role model with similar beliefs can have a beneficial effect on students struggling to accept evolution. Many participants saw their views or beliefs to be in direct opposition to evolution initially. Having a religious scientist model exemplify a way in which students can accept the evidences for evolution and continue to believe was an important factor. It seems some students can accept evolution by simply seeing the evidences, while other students need additional support in order to overcome any conflicts with their worldview and evolution. This is important for instructors to recognize in order to provide their students with the best opportunity to accept evolution.

Factor #3: The reconciliation of scientific and religious worldviews increases acceptance

Science and religion are often associated with conflict; evolution in particular is viewed negatively in relation to religion. Many studies have shown a negative correlation between religion and the acceptance of evolution (Andersson & Wallin, 2006; Coyne, 2012; Heddy & Nadelson & Southerland, 2013; Hill, 2014; Rissler et al., 2014; Schilders et al., 2009). The data collected in this study showed many similar results. For example, the data showed that very religious people were significantly less likely to believe in human evolution prior to college (Figure 4).

Degree of religiosity compared to acceptance of evolution and human evolution at the three different time intervals that were reported. ** indicates statistically significant difference.

As seen in previous studies, religious beliefs can be a very large stumbling block for many students in their journey toward accepting evolution (Andersson &Wallin, 2006; Coyne, 2012; Heddy & Nadelson, 2013; Hill, 2014; Rissler et al., 2014; Schilders et al., 2009). These students (Appendix 2, see ) were able to change their views on evolution after seeing that their beliefs were not in opposition to evolution. In many cases, students were unaware of their religion’s position on evolution; this, along with other misconceptions, led to rejection. It seems that after learning about evolution and in many cases learning their religion’s position on evolution, students were able to reconcile the two and accept evolution.

Human evolution and religious beliefs

Many factors are involved in the students’ process of accepting evolution in general and human evolution. However, as noted previously, there is a difference in the acceptance of human evolution in comparison to the acceptance of evolution in general. It seems, given our data, which included many participants that were highly religious, there are stronger connections with religion’s influence on the acceptance of human evolution in comparison to evolution in general. It is likely that this negative correlation with religion and human evolution is rooted primarily on the explanation for the physical body of humans and how this relates to origin stories and myths. For those that subscribe to the Judeo-Christian tradition, it can be difficult to accept human evolution because they sometimes view a direct contradiction between the Adam and Eve account and the scientifically accepted explanation for Homo sapiens. Interestingly, many of these same believers are able to accept concepts such as natural selection and other laws associated with microevolution.

At the beginning of college, religious students reported being less accepting of human evolution as compared to nonreligious students. This emphasizes the point that reconciliation of human evolution is more complicated for students with religious views. Therefore, religious students would benefit from efforts to reconcile their religious doctrines with scientifically accepted ideas, such as human evolution.

Of the 42 participants, 32 were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and 24 of these did not initially accept human evolution. After the senior-level course, only one participant continued to reject human evolution. Manwaring et al. (2015) studied an even more religious sample consisting mostly of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and found similar results in relation to students’ preliminary acceptance and ability to change their views. Reconciling religion and science is a major factor in accomplishing this change. In their study, an intervention during class was carried out to specifically assist students to find ways to reconcile their views and knowledge of evolution. During a class lecture they “discussed the official church stance on human origins” in order to assist in student reconciliation. Their results show that this intervention played a significant role leading to acceptance of evolution in general and human evolution.

Many of the students in the current study expressed unfamiliarity with their specific religion’s position on evolution. Many participants assumed that their own beliefs contradict the idea of human evolution, causing unneeded resistance toward human evolution. It seems that as students learned more about evolution and their religion and its official position on evolution, their level of acceptance increased. Our results and conclusions align with the general conclusions of Manwaring et al. (2015). Therefore, familiarizing religious students with their own religions doctrine in relation to evolution can have a positive effect on a student’s ability to accept evolution.

Conclusion

Students who navigate through a biology degree change their opinions on evolution. Many who were not able to accept evolution and human evolution at the beginning of their coursework were able to accept it by the time they completed the senior-level course Evolution. There was an increase of 67% when looking at evolution in general, and an increase of 69.2% in association with human evolution. Three factors were prominent in aiding students’ ability to accept evolution and human evolution: (1) the increased knowledge of evolution and the evidences supporting the theory; (2) the influence of a religious scientist role model; and (3) the reconciliation of scientific and religious worldviews. Overall, the factor that tended to have the biggest impact on students majoring in biology was simply seeing the evidences that supported the theory of evolution. These evidences accumulated course after course, such that by the time students are in their last year of college, they mostly accept evolution already, even before taking the senior-level Evolution course. This pathway helped many students clear up preconceived misconceptions about evolution and solidify their acceptance based on the preponderance of evidence. The influence of a religious scientist role model and reconciling religious beliefs were also important, particularly within the religious population. When looking at the factors that helped students accept human evolution, reconciling religious beliefs had a larger impact than compared to accepting evolution in general. This study demonstrates that biology departments that incorporate evolution throughout their core courses enables students to accept evolution in general prior to graduation. Acceptance of human evolution might require a more specific intervention. Instructors should help students recognize the evidences supporting human evolution and should encourage them to reconcile any contradictory views.

Chad Talbot (chad.l.talbot@gmail.com) is a Master of Science student in the Nutrition and Integrative Physiology Department at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Zeegan George is a former undergraduate in the Department of Family, Home, and Social Sciences at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. T. Heath Ogden is an associate professor in the Department of Biology at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah.

Biology Teacher Preparation Postsecondary