Research and Teaching

STEM Scholars’ Sense of Community During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Journal of College Science Teaching—September/October 2021 (Volume 51, Issue 1)

By Jennifer McGee and Rahman Tashakkori

The purpose of this study was to investigate sense of community (SOC) within a STEM learning community during the COVID-19 pandemic. The STEM learning community that was the setting for this study is funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) S-STEM grant. A mixed methods design was used to investigate levels of SOC and changes in SOC from December 2019 to December 2020. Scholars completed the Sense of Community Index (SCI-2) (Chavis et al., 1986) during this time along with answering questions about their experience in the program. Data showed evidence of a slight increase in SOC, when compared to prepandemic SOC. Three themes emerged from the qualitative data to support this finding: community as access, community as sanctuary, and community as sacred. When data were coded for the presence of these themes across time, a slight decrease in the focus on community as access appeared from December 2019 to December 2020, but there were increases in the focus on sanctuary and sacredness of the community. Triangulation of the data provides evidence for this STEM learning community as an important support system for students during this time of unprecedented uncertainty in higher education.

Recruiting and retaining a diverse cadre of STEM majors in higher education is fraught with well-known and widespread issues (Davari et al., 2017; Sithole et al., 2017; Xu, 2016). The need for STEM majors to hold future careers has been made clear (Laros, 2016; Sithole et al., 2017), but there are many factors that influence a student’s decision to remain in their initial STEM major, including financial strain and the quality of the educational environment (Xu, 2016). There is also a concern that STEM programs fail to give students adequate time for extracurricular activities, which has a negative impact on their overall college experience and their desire to complete their degree (Sithole et al., 2017). Other factors such as first-generation status influence students’ intention to depart before degree completion (Ash & Schreiner, 2016; White et al., 2018; Xu, 2016).

Obstacles that impede degree completion for STEM majors have continued to persist even in the virtual educational environment created by the COVID-19 pandemic (Kalman et al., 2020). We believe that STEM students need a strong and resilient sense of community (SOC) in order to persist toward degree completion during these unprecedented times. White et al. (2018) posited that SOC does not develop without intentional interaction among community members and that place is important in creating and sustaining SOC. Toward this idea, the purpose of this study was to examine the persistence and sustainability of STEM scholars’ SOC through a STEM learning community during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following research questions guided this study:

- What were the SOC levels for scholars before and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How has SOC changed for scholars during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Theoretical framework

One proven mitigation strategy for increasing retention and graduation rates in STEM majors is the implementation of learning communities (Dagley et al., 2016; Solanki et al., 2019; Hoffman et al., 2002). Learning communities facilitate the development of relationships between students by combining academic and social interests (Hoffman et al., 2002; White et al., 2019). Interaction with other like-minded students has positive implications for academic and social success of many student groups including low income, first-generation, and minority students (Ash & Schreiner, 2016; Johnson et al., 2020; Solanki et al., 2019; White et al., 2019). Learning communities often function as a cohort model, which has been shown to be a successful model for STEM students in higher education because of the development of SOC (Maton et al., 2016). Overall STEM student engagement can be enhanced through a learning community because of SOC (Jacobs & Archie, 2008). SOC has been associated with important mental health issues such as loneliness and alienation, highlighting the need to consider these factors as essential to student success (Oseguera et al., 2020; White et al., 2019).

Within the field of community psychology, Sarason (1974) first proposed the idea of SOC. This concept was later expanded upon by McMillan and Chavis (1986) and then first measured by Chavis et al. (1986). McMillan and Chavis (1986) asserted that “the experience of sense of community does exist and does operate as a force in human life” (p. 8). They proposed that the measurement of SOC centers on four factors: membership, influence, reinforcement of needs, and shared emotional connection (Chavis et al., 1986). Membership refers to the feeling of belonging and has clear boundaries. Influence is a bidirectional concept that describes both the member’s influence on the actions of the community and the cohesiveness created by the community. Reinforcement of needs consists of all of the various needs met by the community and shared emotional connection details the sense of a shared history and identification as a member of the community (Chavis et al., 1986). The Sense of Community Index-2 (SCI-2) (Chavis et al., 2008) is now widely used to measure this construct in multiple areas including within learning communities (Maton et al., 2016).

Context for the study

Appalachian State University, founded in 1899 as a teacher’s college, has come to be known as the “premier public undergraduate institution in the state of North Carolina” (Appalachian State University, 2021). Appalachian State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System and enrolls more than 20,000 students, offering them more than 150 undergraduate and graduate majors. Situated in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Appalachian State has a well-known reputation for serving the region as well as producing high-quality research.

The learning community that is the focus of this study is the Appalachian High Achievers in STEM scholarship program, which is funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) S-STEM grant (NSF 17-527). This program, called “S-STEM” by scholar participants, is intended to recruit and retain talented, financially needy scholars, many of whom come from rural backgrounds. Five STEM degree programs partner to serve scholars as a part of S-STEM: chemistry, computer science, geology, applied mathematics, and physics. Scholars are admitted into the program from two categories: lower-level/transfer students or upper-level students. Lower-level/transfer students must be in their first year of the major while upper-level students must be within 60 hours of graduation and agree to enroll in graduate school at Southern State to obtain and sustain their funding.

The S-STEM program includes several research-based elements that are intended to support scholars as they transition into the university and assimilate into their degree programs (Davari et al., 2017). First, scholars become a member of a research team each academic semester that has an assigned faculty mentor. The research teams consist of students in complementary majors and focus on a new problem each semester. Scholars also attend weekly study halls with peer tutors and attend an hour-long seminar each Friday. Seminar topics range from academic talks to leadership training. In addition to on-campus programming and other social events, each scholar is assigned an alumni mentor. Specific goals of the S-STEM program are to: enhance undergraduate research experiences, provide emotional support, and provide support for continuing into a STEM career.

Context for on-campus events is important to bear in mind while evaluating the SOC of the S-STEM community both during and before the COVID-19 pandemic. Fall 2019 was a normal semester with all study halls and Friday seminars occurring face-to-face along with team meetings for the research project teams. On March 11, 2020, our campus leadership extended spring break until March 23 when all classes, labs, and other meetings were required to be held fully online. For the S-STEM community, this meant that the Friday seminar became somewhat interrupted, as seminar topics had to shift and be rescheduled. The research teams continued to meet independently online. Fall 2020 brought some uncertainty and many faculty were given options to teach fully online; the majority of classes and labs were held fully online. The Friday seminar continued to be held online during fall 2020, as well as study halls. We will explore these changes below in our discussion of the results.

Method

This study employed a convergent mixed methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). Use of a convergent design mixes data in an effort to obtain a fuller understanding of the research problem (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). Data collection for this study took place during the last Friday seminar in December 2019, May 2020, and December 2020 through a survey, created and deployed using Survey Monkey. Scholars were encouraged to complete the survey each semester, but they were not forced to do so. The survey contained various items of interest to the stakeholders associated with the S-STEM program, including the Sense of Community Index-2 (SCI-2) (Chavis et al., 2008) as well as two open-ended questions: (1) What have been the benefits of working with a faculty person (research mentor) to conduct research in your field of study? and (2) Please share any comments you have about your experiences in S-STEM. Participants also self-reported demographic information.

Participants

In total there were 38 unduplicated participants in this study; primarily undergraduates (84%, n = 32). Graduate students (n = 6, 16%) were included in this study because most participated in S-STEM as undergraduates. The majority of participants were male (63%, n = 24) and White (53%, n = 20). Data collection for this study spanned four cohorts of students entering the program at different times (see Table 1). Most members of cohorts 0 and 1 graduated during the course of this study. Cohort 3 entered into the S-STEM program during the COVID-19 pandemic and was included in this study as they interacted fully with Cohort 2 during the fall 2020 semester.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the levels of SOC present during each instance of data collection (December 2019, May 2020, and December 2020) as measured by the SCI-2 (Chavis et al., 2008). The SCI-2 scores were created by calculating a total sum and then subsequently calculating a sum for each subscale. The highest possible score for total SOC is 72. The highest possible score per subscale (Membership (M), Influence (I), Reinforcement of Needs (RON), and Shared Emotional Connection (SEC) is 18. The SCI-2 has a reported alpha of .94, with subscale alpha coefficients of .79 to .86. Due to the limitations of small sample sizes, only descriptive statistics will be reported.

Qualitative data were then examined using open coding with the two questions from the surveys first coded for the presence of the four factors in a SOC as defined by McMillan and Chavis (1986). Data were then recoded to examine references to the three main goals of the program: Research Experience (RE), Emotional Support (ES), and Career Support (CS). Codes were then transformed into themes and data analyzed again in concert to triangulate findings from both data sets.

Results

Descriptive statistics shown in Table 2 allow for a comparison of SOC scores across time in aggregate. Close analysis of these scores revealed a decline in total SOC and in all four SOC subscales from December 2019 to May 2020. Data revealed a sizeable increase in mean total SOC from May 2020 to December 2020. Across all participants, mean total SOC was greater in December 2020 than in December 2019 (pre COVID-19). Subscale scores for influence, reinforcement of needs, and shared emotional connection were all greater in December 2020 than in May 2020 or December 2019. Membership scores were slightly lower in December 2020 than December 2019, but higher than May 2020.

When total SOC is examined by cohort (see Table 3), some of the same patterns emerged. Mean total SOC for December 2020 remains the highest for each cohort. However, subscale scores by cohort do not mimic the overall patterns shown in SOC in all cases.

Patterns in the qualitative data echoed the patterns in the quantitative data. The highest number of codes for subscales of SOC were found in December 2020. In total, RON was coded most (79 times), M was coded 43 times, and SEC was coded 23 times. There were no codes for I in the qualitative data, likely due to the nature of the questions.

When the same data were coded for the occurrence of program goals, the highest code frequencies were found in December 2020. RE was coded 66 times, ES was coded 60 times, and CS was coded once. See Table 4 for frequency of codes.

Themes

The intersectionality of our codes allowed themes to emerge that captured the various aspects of SOC of this particular community during the time that this study took place. We recognize that these themes may be time bound and contextual, as the COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity to examine the sustainability of SOC during a seismic shift in the norm. As expanded upon above, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our institution was substantial with an extension of spring break in spring 2020 leading into a fall 2020 semester that was full of uncertainty. Nonetheless, we found the themes to be a meaningful interpretation of the shift in SOC and feelings about the community as time has passed.

Community as access

Community as access occurred where the desire for and receipt of context-specific support from the community, as well as access to resources, were mentioned. Access was defined in this study as both access to resources (i.e., software, hardware, lab spaces) and also access to expertise (i.e., mentors, peer mentors, faculty). This theme remained a constant at each data collection point and highlighted the academic nature of the learning community that S-STEM provides to scholars. Participants consistently shared that subject-specific knowledge was a valued part of this community and that students otherwise would not normally have access to some of these knowledge-building experiences. This theme appeared in the data a total of 81 times.

Some responses within this theme were straightforward such as, “I’ve begun to learn how to program.” Other responses focused on the role of the research mentor: “My research mentor has been extremely patient and been helpful throughout the research process.” Mentors were viewed as a “guide” and sometimes mentioned by name: “Dr. N [pseudonym] has helped us set up Unreal on the lab computers and work on our project.” “When we get stuck we can go to Dr P [pseudonym] for help.”

In May 2020 and December 2020, responses within this theme became more elaborate and detailed, and presented a shift toward the valued resource in the community being people (experts, faculty, other students) and away from the research project, technology, and software. One such comment in May 2020 was, “I think I have benefited from working with Dr. C [pseudonym] because she not only leads our research, but she also helps us plan our classes and how to move forward towards our degrees and provides personal mentorship as well.” Additionally, one scholar commented that, “It is great having a research mentor to guide you along the process and make sure that you and your group are learning and investigating new topics.” Academic goals beyond undergraduate degrees and career goals were also mentioned by participants with relevance to this theme. One scholar commented in December 2020 that, “It’s been helpful to have someone not only be an aid in research but also be helpful in other aspects.” Another commented that the research mentor was helpful for “getting a different point of view on research and industry.”

Community as sanctuary

One definition of sanctuary is “a place of refuge and protection (Merriam-Webster, 2021). The theme community as sanctuary reflected feelings about being connected to others in the community. Responses coded underneath this theme became longer, more detailed, and in many cases more heartfelt from December 2019 to December 2020. This theme appears a total of 55 times. Participants reflected a sense of appreciation for the community as a safe space while also echoing the importance of relationships: “Stem [S-STEM] has helped me greatly with academics and also with making friends.” One student shared, “I really enjoy the atmosphere and the sense of community and family that has been built up over my time in the program as well as the opportunities and connections it’s allowed me to make.”

There are other responses in both semesters of 2020 that reflect the idea of trust within the community. We considered trust to be something greater than just being connected and reflected a deeper bond within the community. Some of the responses that fell under this theme were quite detailed. One scholar shared, “I am able to have a chemistry teacher who I can send questions to if needed and simply by developing a relationship with her I feel more connected and confident in my major.” Another shared their experience after several years of connection with the community by stating, “Since I started the program my freshman year, I’ve had the same professor research mentor and she has been great. The biggest benefit [of S-STEM] would be having someone you trust to go to with questions and/or concerns.”

Community as sacred

The final theme, community as sacred, aligns with the following definition from Merriam-Webster as “highly valued and important” (Merriam-Webster, 2021). This theme appears a total of 74 times in the data. In December 2019, participants remarked about being “grateful” for the experience, or “enjoying” the program. One such statement from a student was, “I enjoy coming together to do research sometimes on shared interests.” Another was, “I really enjoy and feel as though I benefit from this program!” In May and December 2020, more participant responses referenced membership in the “S-STEM” community than in December 2019, naming the community in their responses and fully elaborating on their feelings about the program. There were many references to appreciation of belonging to something and connecting to something. One student shared that, “This has been a hard year that I have made through thanks to the S-STEM community.” Another elaborated by stating, “The S-STEM program has made my time at [Southern State University] in the program significantly better. It is an excellent community and they have helped me tremendously personally and professionally.” Other scholars commented, “It has been very helpful as a support system especially being at home so much during quarantine” and “I love having a group of people that care for me!” One of the most powerful comments in the study was coded within this theme as well: “Every time we meet up, it feels like meeting with family and friends so it is very nice to have in times when I can’t visit my family and friends.”

Sense of community before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

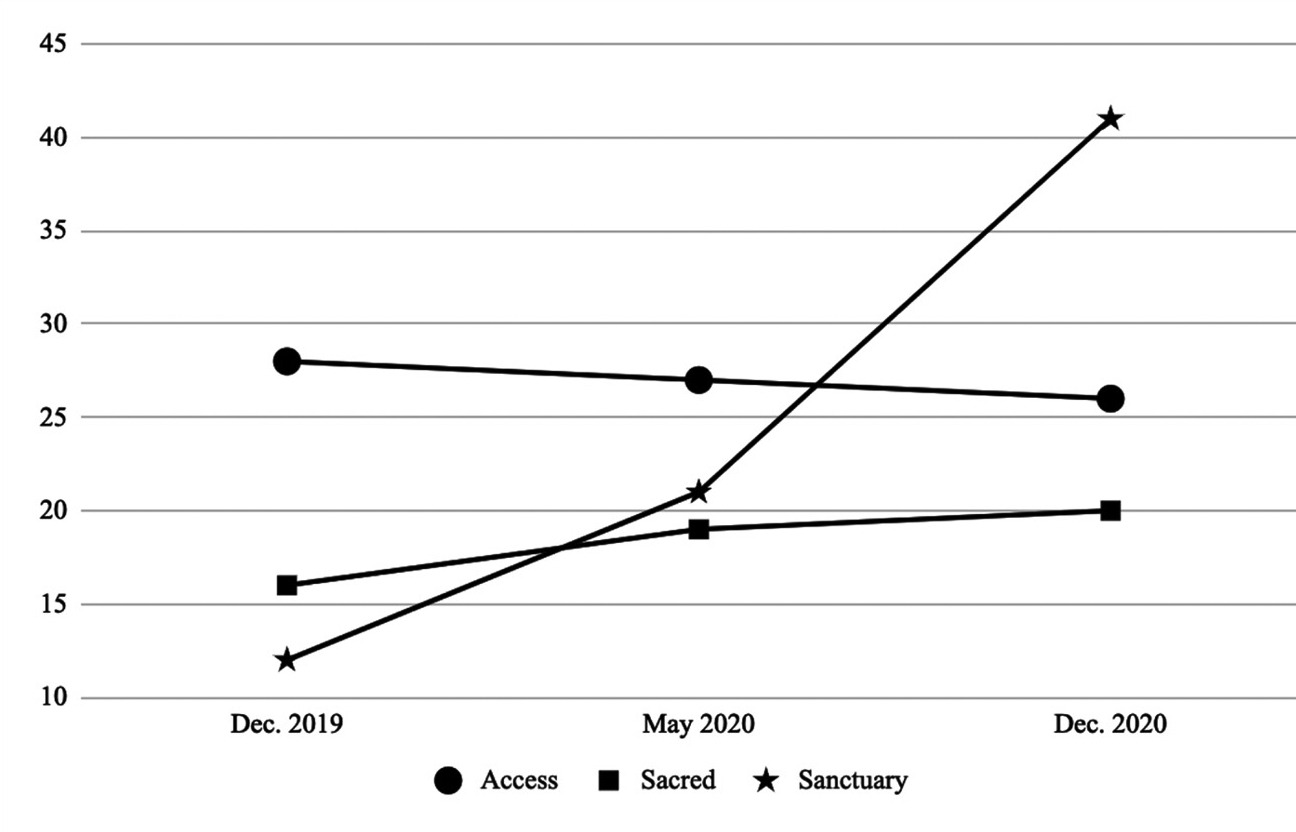

We found it important to examine the frequency of our three themes across time in order to investigate the persistence and sustainability of SOC during the COVID-19 pandemic and were surprised by the results. Figure 1 details the trends that emerged once scholar responses were coded thematically. We found that community as access showed a slight downward trend, occurring slightly less frequently in May and December 2020 than in December 2019. An opposite pattern appeared in the trendlines for the other two themes. Community as sacred occurred slightly more frequently across time, with participants mentioning the S-STEM community by name in many of their responses and detailing the value of membership in the community, especially during the pandemic. Community as sanctuary also occurred more frequently across time with a large increase in December 2020.

Frequency of sense of community themes across time.

While the findings we will discuss are valuable to our program we feel that they are also valuable to other learning communities and show value to the field as a whole as these communities are serving a very real purpose for students during a trying time. The discussion will detail our general findings and the significance of those findings along with limitations and recommendations for future research.

Discussion

In this study, our intersectionality of the two coding schemes showed quite a bit of overlap, causing us to examine the ebb and flow of responses to different aspects of SOC, both before and during the end of the pandemic. After the data were thoroughly triangulated, we feel confident in asserting the validity of our findings. White et al. (2018) noted the importance of place in establishing community. Place was defined as “classes, residents, halls” (p. 814). However, we now think of online classes and meetings as “places” as well and it seems possible that virtual places will continue to fill an important role in establishing SOC for college students. The movement of S-STEM community activities into virtual spaces seemed to not have a negative impact on overall SOC of this learning community. Quite the contrary, SOC remained strong and even increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. We were surprised by what appeared to be an increase in mean SOC from December 2019 to December 2020 and an increase in most all subscales of SOC. As the fall 2020 semester was offered almost fully online campus-wide, and the Friday seminars were also online, a dramatic drop in SOC was expected.

We also found value in examining the trends in the qualitative data with regard to SOC and think the trends are of value in considering the possible impact that the pandemic has had on SOC within S-STEM. We found that our scholar participants first connected to the S-STEM learning community academically and then emotionally later on. It was fascinating that responses to questions about the research mentor and the program in general shifted in focus from an appreciation of the community as asset-rich to the community as emotionally rich.

Feelings about membership in the community shifted from “enjoyment” to “gratefulness.” Major changes occurred during the time of this study on our campus. All students in March 2020 were asked to leave campus and return to their homes. As disruptive as this directive was for academic environments, it also caused unprecedented emotional disruption to college students (Kalman et al., 2020). As participants clearly noted, there were times when they were unable to gather with their own family and friends and the S-STEM community was able to fill this role in their lives. Additionally, our S-STEM scholars come from various communities and family structures, are diverse, and many are first-generation college students. Responses from the scholars during May and December 2020 show without question that S-STEM remained a lifeline for them to campus, faculty, and friends.

We entered into this study with the intention of merely examining the levels of SOC present within the S-STEM learning community. The literature on learning communities is rich and the value of the learning community to retention and degree completion cannot be understated. Learning communities themselves, during normal academic semesters, bolster students and keep them persisting toward degree completion (Hoffman et al., 2002; White et al., 2019). We believe that in these uncertain times, when we are still operating in a more virtual academic environment, that there is added value to our S-STEM community to support and sustain our scholars both in degree completion and emotionally. This study includes significant findings for both the learning community literature, SOC research, and the emerging research around the COVID-19 pandemic and impacts on institutions of higher education.

Limitations

Although the use of mixed methods allows for investigation of SOC within a small STEM learning community, the lack of a large sample size creates an obstacle for examining these constructs inferentially. The use of only descriptive statistics for measuring a psychological construct likely has more utility for applied research and evaluative purposes. Empirically, we cannot attribute causation of an increase in SOC to the S-STEM learning community through the pandemic. Furthermore, as this study took place at a single institution, its findings may not be generalizable to other institutions or other STEM learning communities. With these limitations in mind, we have recommendations for future research that will lead to generalizable findings.

Recommendations for future research

There are many interesting avenues to explore regarding SOC in STEM learning communities. First and foremost, more intensive qualitative research would contribute a rich and deep understanding of the relationships at play between our scholars and their peers and mentors. Future studies should seek to examine constructs not explored in this study such as influence of community members on the community and vice versa. As these data are a snapshot in time, future research should continue to examine community aspects that might contribute to SOC. As mentioned above, there is a burgeoning field of study around the COVID-19 pandemic and impacts on multiple aspects of society and on institutions of higher education. Future researchers should further explore how STEM learning communities buffer isolation and mental health issues for college students navigating uncharted waters as young adults, students, and scholars. Additionally, there remain many opportunities for research around virtual and online learning communities and how those communities function, support each other, and recognize members of the community through shared experiences. ■

Acknowledgments

The learning community that is the focus of this study is the “High Achievers in STEM” scholarship program, which is funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) S-STEM grant (NSF 17-527).

Jennifer McGee (mcgeejr@appstate.edu) is an associate professor of educational research and evaluation in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction and Rahman Tashakkori is department chair and Lowe’s Distinguished Professor of Computer Science in the Department of Computer Science, both at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina.

Research STEM Teacher Preparation Postsecondary