start with phenomena

Fostering Cultural Community Wealth

Using community centered phenomena to develop paramount tasks

Science and Children—March/April 2023 (Volume 60, Issue 4)

By Kelley Woolford Buchheister, Christa Jackson, and Cynthia E. Taylor

The 2019 flood that hit the Midwest devastated the agricultural community and contaminated local water systems, which placed an overwhelming number of people in a state of emergency. This situation provided an opportunity to connect students—both prospective teachers and preK–12 learners—to relevant and meaningful experiences that stimulate scientific reasoning by using community-centered phenomena as a catalyst for developing paramount tasks. Paramount tasks intersect culture and community, conceptual content, and connected resources. Using this framework, we engaged PTs in a collaborative planning activity that showcased how paramount tasks can foster learners’ understanding of content, emphasize community connections to environmental hazards resulting from the local flood, and related to a children’s storybook depicting a fictional Sudanese family’s experience with contaminated water.

In 2019, a low-pressure storm intensified quickly and brought heavy precipitation, winds, and flooding that had detrimental effects in the Midwest. This “bomb cyclone” devastated the agricultural community, resulting in millions of dollars in flood damage to roads, bridges, homes, businesses, farmland, and cattle. During this state of emergency, our Midwestern elementary and early childhood prospective teachers (PTs) were in the midst of their final student teaching internship where they were expected to fully engage in the K–5 classrooms as educators—planning, implementing, and assessing activities that promote learners’ understanding of key concepts through relevant and meaningful lessons. The PTs, particularly those placed in rural schools, learned about the reality of the impact of these disasters on children, families, communities, and their learning.

Situations or events that immediately impact the local community also provide tremendous opportunities to connect learners—both PTs and preK–12 students—to relevant and meaningful connections to science, scientific literacy, and integrated STEM activities that build from their inquiries and observations. Experiences like the 2019 “bomb cyclone” can stimulate valuable conversations about the PTs’ role as educators and members of the local community. As methods instructors, we strive to foster our PTs’ scientific habits of mind, facilitate scientific reasoning, and cultivate PTs’ capacity to plan experiences that are grounded in community-centered phenomena. Furthermore, we want to create opportunities in which PTs examine how scientific concepts can be explored through questions that emerge from learners’ observations.

Due to the flood’s impact on the water supply, our PTs highlighted the struggles their school-age families faced from the contamination and the community’s limited access to fresh water. From these conversations we recognized how PTs’ questions and ideas aligned to grade-level content within the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS; NGSS Lead States 2013). Thus, we intentionally shifted our subsequent seminar discussions to implement a shared planning experience describing the elements of a paramount task, demonstrating how to use community-centered phenomena as a catalyst for developing paramount tasks and outlining the process, which PTs could also follow when planning lessons and activities as practicing teachers.

Defining Paramount Tasks

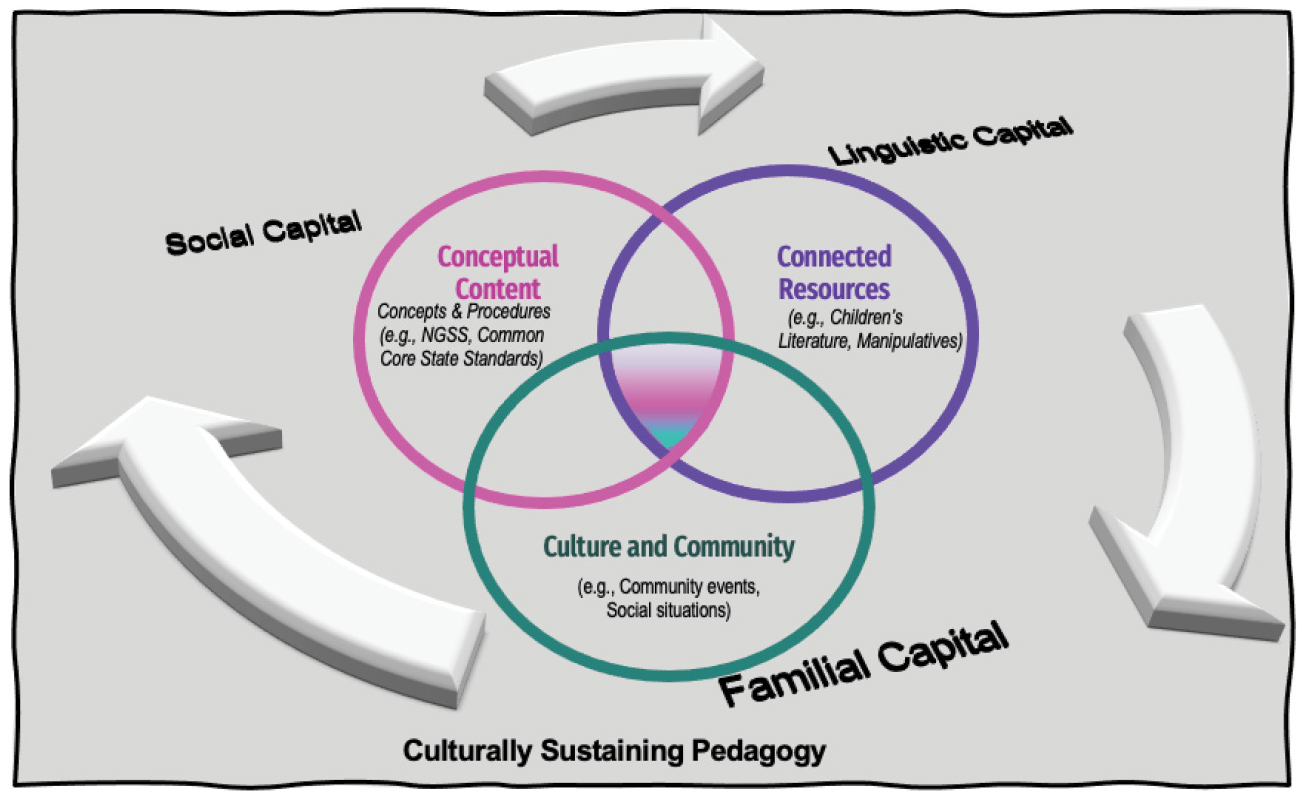

Paramount tasks reflect developmentally appropriate activities that are situated in environmental and community contexts. Like high-quality tasks, paramount tasks are accessible to learners through multiple entry points or various solutions, require high levels of cognitive demand, and encourage learners to make connections among ideas (Breyfogle and Williams 2008). Paramount tasks occur at the intersection of (a) culture and community, (b) conceptual content, and (c) connected resources (Figure 1) and are bounded by culturally sustaining pedagogy. Culturally sustaining pedagogy honors, explores, and extends students’ cultural wealth (i.e., communication practices, family and community traditions, societal support systems), which in turn highlights how classroom constructed knowledge should return to the community. Thus, for students of color or students from other marginalized populations, a culturally sustaining classroom can inherently bridge theory to practice, classroom to community, and history to future by centering the voices of each and every student.

Intersection defining paramount tasks.

Paramount tasks are purposefully planned and intended to be implemented through the lens of three forms of learners’ community cultural wealth: (a) diverse communication experiences (linguistic capital), (b) families’ sense of tradition and community (familial capital), and (c) support systems for navigating institutions (social capital) (Yosso 2005). Through paramount tasks teachers and teacher educators can support learners’ understanding of the key concepts and ideas related to the anchoring phenomena by intentionally planning experiences in which learners apply content knowledge, concepts, procedures, or practices as they deepen their understanding about culture, explore community events, investigate complex social issues, develop innovative solutions to local obstacles, or intentionally work toward dismantling existing systemic barriers.

Creating a Paramount Task

As PTs entered the subsequent seminar they were greeted with this excerpt from a classmate’s reflection:

“My students still don’t have water. Well, I mean they have water. They just can’t use it for anything unless they boil it first. It’s still contaminated. I never realized how much we take advantage of things in life. It seems so simple that we just go to the faucet and have fresh water to drink, or even just to brush our teeth. I cannot imagine what it would be like to live someplace where it’s like this all the time. Are there still places around the world that don’t have access to fresh water every day?”

We asked PTs to discuss the quote with their tablemates and document any ideas or questions it raised. The PTs shared how their students and families struggled to find clean water and were concerned about how the community would get access to bottled water or other supplies when certain areas were isolated due to washed out roads and bridges.

After the discussion, we displayed the framework for paramount tasks and introduced how the phenomenon of the natural disaster could be used as a catalyst for creating a paramount task. In terms of the cultural and community component of the framework, we emphasized how the “bomb cyclone” affected the community’s access to fresh water. We asked PTs to generate a list of science concepts or principles that could be explored through the natural disaster. As a whole group, PTs identified various concepts (i.e., conceptual content) such as weather, the water cycle, measurement, and erosion. Next, we collaboratively identified tools (i.e., connected resources) we could use to make connections and support a shared learning experience, which included materials such as manipulatives to build levees, newspaper articles from around the community to compare the impact, or children’s literature for shared reading.

We also highlighted how children’s literature can serve as an additional bridge between the content, the learners’ community, and the surrounding world (McDuffie, Ward, and Young 2018) and explained that we would select a storybook as our connected resource. Then, we discussed the steps (Table 1) in creating a paramount task and explained we would collaboratively develop a paramount task for second-grade students that would promote scientific inquiry.

We began the shared planning exercise by revisiting the learners’ and their families’ assets, which PTs described in previous discussions. During those conversations, PTs’ identified how their classroom families engaged in the different disciplines of science, particularly highlighting specific community efforts including engaging in innovative problem-solving and applying engineering design practices. For example, the PTs shared that their learners and families could use cheesecloth or coffee filters to remove debris from the water before boiling it over firepits to decontaminate it. In addition, the children wondered how they could get bottled water to their community when the roads were impassable. The PTs recalled the children used critical and creative thinking as they suggested how air mattresses and pool noodles could be used to transport the water. From that point, we emphasized how we addressed the first two steps in developing paramount tasks by identifying assets and recognizing community connections.

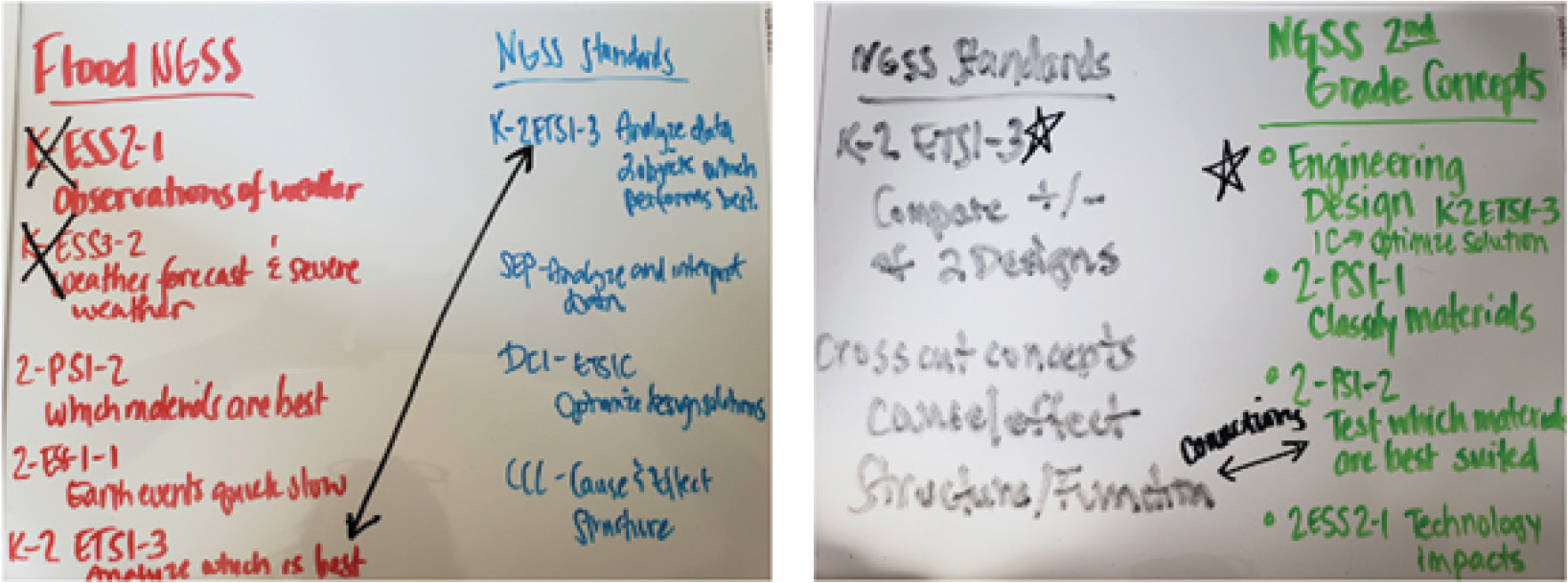

Next, we asked PTs to review the NGSS and establish specific content goals that could be situated within the context of the flood and explored through developmentally appropriate investigations. We organized the PTs into small groups and asked them to identify connections between the local flooding situation and the three NGSS dimensions for grades K–2. The PTs identified different focal points across the three dimensions (see Figure 2) and shared their ideas with the class. In this discussion, the PTs noticed each group identified the same NGSS standard, K–2 Engineering, Technology, and Application of Science (K-2-ETS1-3) (NGSS Lead States 2013).

NGSS brainstorming session.

In the whole-group discussion, PTs highlighted key ideas within the disciplinary core ideas (DCI) demonstrating how families engineered filtration systems or applied scientific concepts to build fires for boiling water when they were faced with limited resources, including power outages, gas leaks, or unreliable access to supplies in local stores. The emphasis on the need for clean water and families’ approaches to filtering water led PTs to connect crosscutting concepts (CCC) such as structure and function, as well as exploring the cause-and-effect relationship between the flood and the contaminated water systems. Finally, groups shared that the various ways the families engaged in problem-solving and scientific thinking related to numerous scientific habits of mind and showcased the science and engineering practices (SEPs). One PT’s reflection summarized the three dimensions addressed through the local phenomenon.

“At first we only thought the kids would be identifying the problem or asking questions about the flood [SEP]. We thought about how families used things like cheesecloth or fabric or old coffee liners they had to think about the structure of the materials and how it needed to work to filter water [CCC]. That’s building models and planning investigations [SEP]. They also applied scientific knowledge because they realized they still had to boil the water if they wanted to drink it because there were probably still microscopic bacteria. The flood damaged the power lines and gas pipes and most of my families didn’t have generators; so they had to figure out how to build fires and boil water over those fires [DCI]. There was a lot of scientific thinking, and we can have them do something similar but also add collecting and analyzing data so we can include more math [K-2-ETS1-3].”

After analyzing the standards, we read the story Nya’s Long Walk (Parker 2019) with the PTs and asked them to think about how the story compared to situations in their local community and around the world. Then, as a group, we evaluated the resource using criteria for culturally sustaining literature (see Table 2).

In the process of evaluating our selected resource, PTs identified connections to Sudanese language and vocabulary, such as the pronunciation of Nya (NEE-yah) and terms such as jerry can, (linguistic capital) included in the story. Furthermore, PTs noted the explicit focus on the cultural community highlighted in the book and how the people of Sudan experienced limited access to clean water, much like the people in their local area. In addition, the PTs commented on Nya’s strength and resilience as she carried her sister back to the village and connected it to the innovative ideas and perseverance the children’s families exhibited when they engineered tools to filter particulates from their water. The PTs also recognized cultural traditions of the Sudanese children such as chores of fetching water or hand clapping games (familial capital). Connecting local environmental issues and concerns and those experienced by people around the world also helped PTs recognize that access to clean water and sustainable filtration systems are vital to individuals’ health and the well-being of the community (social capital).

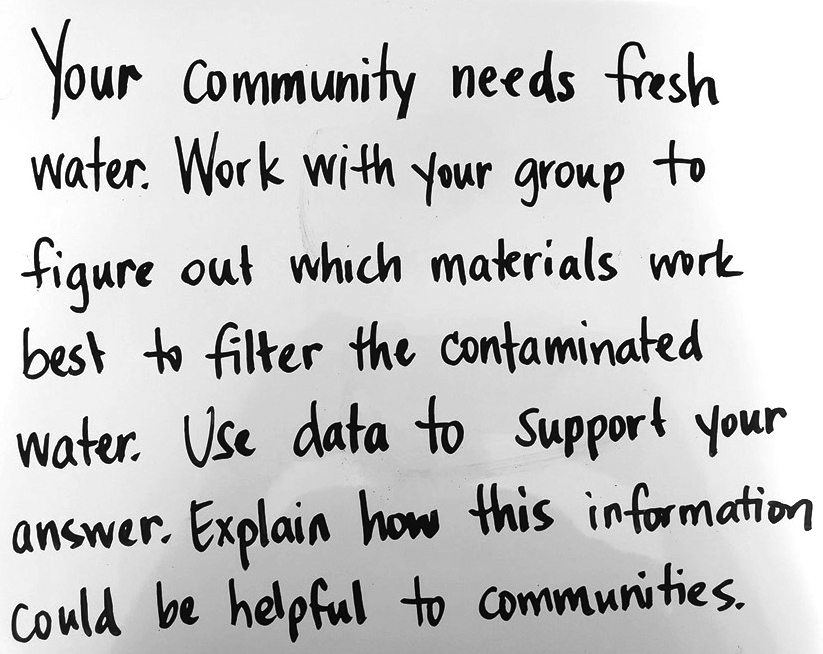

Finally, we asked PTs to brainstorm a specific task they could use to build on children’s experiences, explore the big ideas from the NGSS, and integrate key connections to the selected story. Reflecting on the events of the story, we prompted PTs to work in small groups to develop a second-grade task that would emphasize the standards they identified in the previous group activity and also reinforce the dynamic interplay among content, community, and connected resources through a culturally-sustaining lens. After each group created their paramount task, one representative from each group shared the task with whole group and we led the PTs in a discussion to evaluate the structure of each task. Then, we collectively developed the final paramount task (Figure 3).

Final paramount task.

Discussion

Paramount tasks, similar to the one the PTs created connecting Nya’s Long Walk to the 2019 flooding from the “bomb cyclone” in the Midwest, can develop learners’ critical consciousness by problematizing situations in the real world. Collaboratively engaging PTs in this planning process provides opportunities to emphasize how the nature of the NGSS is reflected through paramount tasks. Paramount tasks are grounded in criteria that develops learners’ scientific literacy as they explore practical problems, identify how STEM content is modeled through community-centered phenomena, and analyze community events or cultural practices in our world. The unique interplay among the elements that comprise a paramount task affords teachers and teacher educators greater opportunities to develop rigorous problems intricately connected to the learners, their communities, and their cultures. This approach to planning not only reflects the hallmark of the NGSS, but also positions learners and the events or ideas relevant to them and their communities at the forefront of their learning.

Kelley Woolford Buchheister (kbuchheister2@unl.edu) is an associate professor of Child, Youth, and Family Studies at University of Nebraska—Lincoln in Lincoln, Nebraska. Christa Jackson is a professor of Mathematics, Science, and STEM Education at Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri. Cynthia E. Taylor is a professor of mathematics at Millersville University of Pennsylvania in Millersville, Pennsylvania.

NGSS Phenomena Three-Dimensional Learning