Diversity and Equity

Broadening Equity Through Recruitment: Pre-College STEM Program Recruitment in Literature and Practice

Connected Science Learning November-December 2021 (Volume 3, Issue 6)

By Lori Delale-O'Connor, Alaine Allen, Mackenzie Ball, David N. Boone, Rebecca Gonda, Jennifer Iriti, and Alison Slinskey Legg

The National Science Foundation (2019) points to Black, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Island peoples as underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) college majors and professional pathways. This underrepresentation results from an interplay of representation and process, meaning that it in part results from STEM opportunities and programming that do not reflect the experiences of racially and ethnically diverse people, offer insight into the needs of diverse communities, nor address barriers that prevent participation (McGee 2020).

One way that institutions of higher education (IHEs) and community organizations try to address inequities in STEM is through pre-college programs aimed at supporting racially and ethnically minoritized (REM) youth. These pre-college STEM programs (PCSPs) work to foster increased STEM awareness and support students in achieving academic milestones that make college pathways more viable. Out-of-school learning (OSL) and informal STEM programming have the potential to fill gaps in STEM K–12 education, as well as complement and support connections with K–12 STEM by offering REM youth opportunities to connect STEM with their lives and influence both their capabilities and dispositions toward STEM (Kitchen et al. 2018). Studies have pointed to positive connections between OSL STEM participation and outcomes such as high school graduation, sustained interest in STEM, and matriculation to university (Penuel, Clark, and Bevan 2016). PCSPs may also support IHE’s development of infrastructure to increase admissions of REM students into college STEM programs.

For PCSPs to be an effective element of reducing inequities in STEM, they must successfully engage with and recruit REM youth to participate. In this article, we focus on the recruitment of REM youth into STEM OSL to better understand what is effective for REM youth and their families, as well as highlight connections between OSL and in-school STEM opportunities. Our goals in this work are to (1) identify program practices with the aim of broadening STEM educational and career pathways for REM youth and (2) support strengthened pathways between STEM in K–12 schools and IHEs.

Methods

To better understand successful recruitment of REM youth into PCSPs, we connect two sources of data: (1) extant research and evaluation on recruiting racially minoritized students into OSL STEM and (2) program recruitment data gathered from interviews with four PCSP directors and a small survey of REM youth who participated in programs offered by their organizations. We gathered these data as part of larger National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation–funded projects focused on broadening equity in STEM. We describe each data source in detail below.

Data and Contexts

We engaged in a literature review of “best” and promising practices of recruitment focused on OSL aimed toward REM youth, summarizing our findings along three thematic and action-focused categories: (1) focus information sharing on REM youths’ lives and experiences; (2) demonstrate program relevance to REM youth, their families, and communities; and (3) eliminate obstacles and barriers to participation of REM youth. Then, we connected these findings from the literature to the data collected from the four PCSPs participating in this project. To gain an understanding of these PCSP’s existing program recruitment practices, we engaged in reviews of: recruitment documents (including websites and print and digital documents); formal interviews and other discussions with program directors about their recruitment process; program director self-assessment of practices; and a brief survey with former REM youth program participants. All of the participating PCSP program directors are authors of this article.

The four PCSPs that are part of this study are affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, a primarily white, urban university located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The PCSPs (all in different STEM fields—biology, biomedical engineering, engineering, computer/information science) each work to recruit REM youth and connect them to STEM experiences. Despite differences in focus, structure, and content, the programs share a mission of enhancing students’ interest and capabilities in STEM so they can attend college and major in a STEM field. The programs are described in Table 1 (see Supplemental Resources), and a detailed table of their recruitment practices is available in Appendix A: Program Recruitment Methods and Materials (see Supplemental Resources).

Findings and Promising Practices

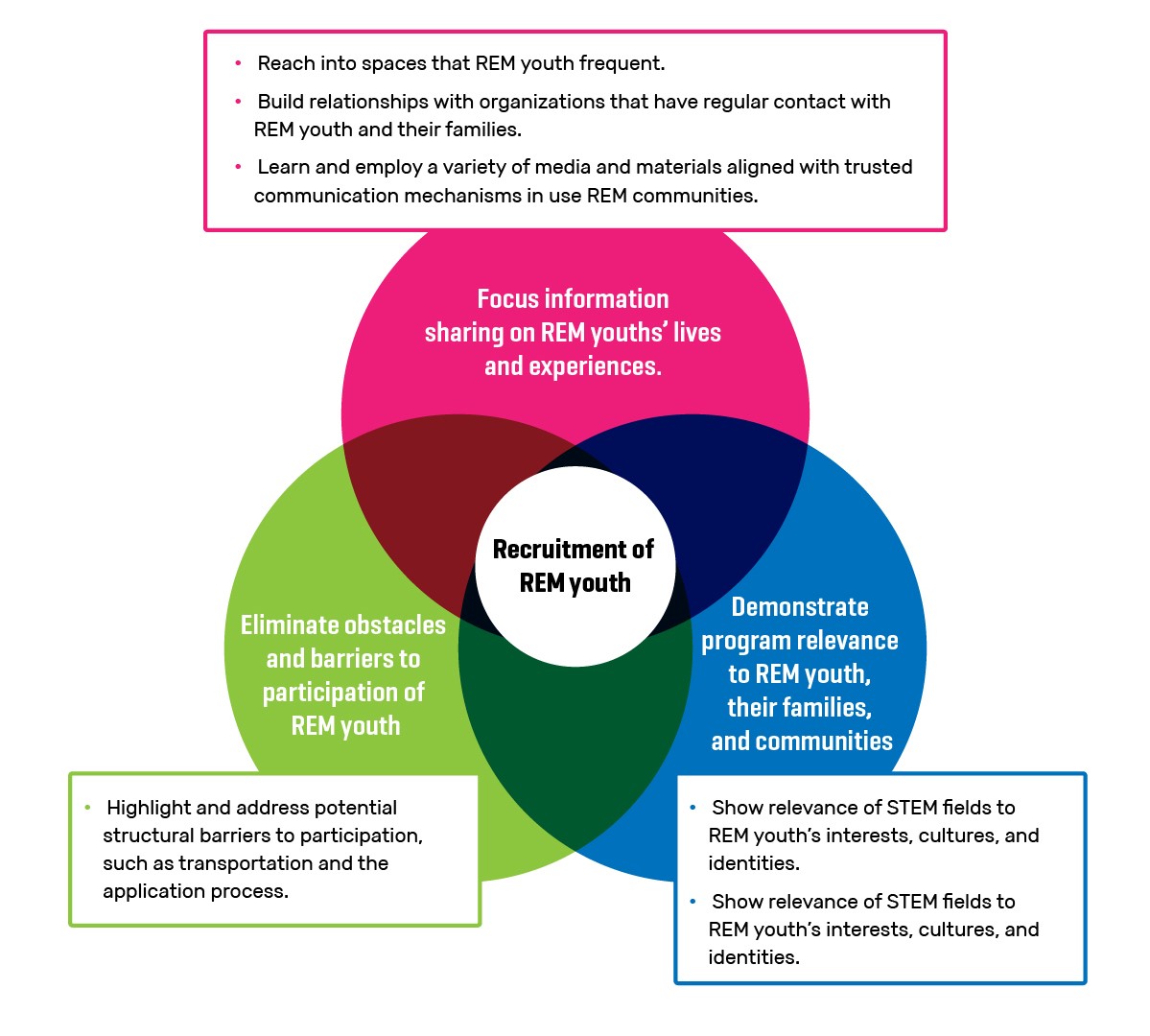

Broadly, youth are drawn to OSL STEM programs in many ways and for many reasons. In Figure 1, we outline and expand on three themes and associated research-informed practices for recruitment of REM youth, as it may differ from the recruitment of white, middle and upper-class youth. Specifically, the themes are: (1) focus information sharing on REM youths’ lives and experiences; (2) demonstrate program relevance to REM youth, their families, and communities; and (3) eliminate obstacles and barriers to participation of REM youth. For each theme we also share a narrative of success from one of the four programs described in Table 1 about how these themes can be implemented in practice. All themes emphasize the importance of being culturally and contextually responsive to youth and their families—understanding youths’ familial and community backgrounds, ways of understanding and engaging the world, needs, and networks. We offer these themes as adaptive rather than prescriptive because the youth and communities that programs seek to serve vary greatly, despite potentially shared marginalization.

Focus information sharing on REM youths’ lives and experiences.

Studies have pointed to the value of understanding and aligning programs and recruitment strategies with the young people programs seek to serve (Henriksen, Jensen, and Sjaastad 2015; Lyon, Jafri, and St. Louis 2012). Related practices include:

1. Reaching into spaces that racially minoritized youth frequent (O’Sullivan, Strumpf, and Barnes 2017). One aspect of outreach that was prevalent in the literature is the importance of meeting youth where they are—literally. This means engaging in program information sharing and outreach targeted to REM youths’ spatial and practical realities, including schools, community programs, houses of worship, and recreation spaces.

Example: The Technology Leadership Initiative (TLI) deliberately disseminates program information in schools, programs, and other spaces that already serve REM youth. The director of TLI has developed relationships with local high school teachers and guidance counselors, as well as other STEM programs. TLI successfully recruits REM youth by

-

Visiting and presenting in local classrooms, as well as at other STEM programs.

-

Developing and sharing flyers, brochures, and email invitations with local teachers and guidance counselors to share with their students.

-

Advertising through other STEM and non-STEM OSL programs.

These practices deliberately center both broad and specific information sharing. In literature and practice, programs found this can also include posting or sending information and/or program representatives to identified community stores and the local housing authority as well as going door to door.

2. Building relationships with organizations that have regular contact with racially minoritized youth and their families (Barnes-Proby et al. 2017; Delale-O’Connor et al. 2016). Building deliberate and ongoing connections with schools, community-based organizations, and places of worship were also found to be effective ways to both disseminate information and garner trust from families and youth. STEM programs that can partner with schools and other organizations also have a direct connection to students, families, and educators. Further, they may be able to enhance or support in-school practices and programming. In some cases, this alignment is reciprocal in that the programs were designed in conjunction with K–12 educators or other partners to fulfill requirements of school or other programming. For instance, programs might offer curricula, materials, or hands-on opportunities to support classroom educators. Other connections may be more strategic, such as programs focused on a population that would be likely to attend because they were required to be there (e.g., summer school). Close proximity—programs held in schools or nearby spaces—can facilitate collaboration opportunities with youth and staff from these other sites and aid in recruitment efforts.

Example: The Hillman Academy partners with schools and other organizations in deliberate ways. They successfully recruit REM youth by

-

Connecting directly with Pittsburgh Public Schools (local school district), including developing relationships with district administration (principals, curriculum coordinators, and gifted coordinators), STEM teachers, and student organizations.

-

Providing scientific equipment and lessons for school classrooms to support curricula.

-

Developing referral relationships with community-based, faith-based, and funding organizations that focus on supporting REM youth (such as Funding for the Advancement of Minorities through Education (FAME), the Homeless Children’s Education Fund, and MPowerhouse).

-

Offering guaranteed admission slots for youth referred by community partners.

These practices deliberately center relationships with K–12 schools and community organizations that support youth.

3. Learning and employing a variety of media and materials (Barker, Killian, and Evans 2010; Gillard and Witt 2008; O’Sullivan, Strumpf, and Barnes 2017). Engaging the modes of communication valued by REM youth as well as their families and communities offers an effective way to recruit. This includes engaging traditional media outlets (newspaper, radio) as well as developing and maintaining an ongoing social media presence (e.g., Snapchat, Instagram). It is particularly important to recognize if a community has specific sites or channels that are trusted sources of information (e.g., a Black newspaper; Spanish-language radio station). Inclusion in community distribution lists (postal mail or email) may further enhance both research and credibility. While challenging to measure, “word of mouth” from school and program staff, participants, and families is also an integral recruitment channel that can be deliberately cultivated. This means drawing upon youth, their families, and program staff (particularly those that are part of the community) in systematic ways such as

-

training youth to actively engage their peers (e.g., peer counseling, peer referral forms),

-

creating an advisory council of youth and families (e.g., prior and current participants), and

-

offering stipends for referral.

It can also include reaching out to and seeking referrals from, for example, religious leaders, peers, and housing authority representatives. In some instances, engaging funders was found to be effective as a potential recruitment source, particularly in cases where the funders have broader reach or support-related programs.

Demonstrate program relevance to REM youth, their families, and communities.

Studies demonstrate that many REM youth are motivated to engage in STEM when they believe it has clear potential to improve their own communities’ infrastructure and experiences (McGee and Bentley 2017). While there are variety of ways to do this, a few keys ideas appear consistently in the literature. These ideas focus on having students develop and frame the issues they see as most relevant to their communities—such as air and water quality or food access—as well as demonstrating the value of youths’ cultural understanding in addressing these issues, for instance, bringing in indigenous approaches to STEM (Honma 2017; Wright 2011). Specific practices include:

1. Recognizing and aligning REM supporting program practices with recruitment (Burke 2007; Milgram 2011; Parker, Kruchten, and Moshfeghian 2017; Roberts et al. 2018; Wright 2011). While programmatic practices and curricula are typically associated with retention, they also play a role in recruitment. In particular, because successful programs foster strong word of mouth, youth will hear about “good” programming from friends, community leaders, and teachers—and former participants will continue to come back. High-impact programmatic practices vary, but studies indicate that successful STEM OSL incorporates hands-on learning such as action, experiments, engaging in design processes, or other tasks that correspond to STEM work. Specific to engaging REM youth, some suggestions across the literature included organizing science identity workshops that talk about history, engaging REM STEM experts, and organizing peer teaching teams that encompass a broad age range of students.

Example: INVESTING NOW connects recruiting and programming explicitly to the importance and relevance of STEM to REM youth. These practices include

-

Program components focused on family and community connections, including college and career planning and family events.

-

Bringing in REM professionals as role models to talk about their experiences in STEM.

-

Hosting an annual Career Awareness seminar to demonstrate STEM relevance, which can also lead to additional opportunities such as career shadowing experiences and internships.

These practices connect to both family and broader STEM communities, as well as demonstrate an ongoing commitment to REM youth and their futures in STEM.

Eliminate obstacles and barriers to participation of REM youth (Gillard and Witt 2008; Lyon et al. 2012; Little and Lauver 2005).

Research and practice have pointed to a number of structural barriers that make participating in OSL harder for REM youth—many of which are not specific to STEM programming yet still have clear implications for these programs, including confusing application processes; registration fees; lack of prerequisite knowledge, skills, or experiences; lack of transportation; and high-opportunity costs for other engagement (e.g., childcare, work, and other activities). Associated solutions require first identifying the barriers, which can be done in conjunction with current participants and their families, as well as schools and other community organizations. Viable solutions vary greatly but include

-

clarifying application processes (e.g., providing examples, videos to walk applicants through the process) and application support at open houses or outreach events and

-

providing transportation or moving the programming venue to the communities where the program hopes to attract participants.

Studies have also suggested modifications such as changing meeting times to avoid coinciding with other responsibilities.

Example: Gene Team works to eliminate barriers throughout the application process and during the program to allow participation from students throughout the Pittsburgh Public School District:

-

Applications are available in a variety of places online, and paper applications are distributed with teachers and community leaders for youth who may not have online access.

-

Students are interviewed to be part of Gene Team at the students’ high schools rather than requiring them to travel to the university.

-

Participants receive a stipend for participation and a bus pass that gives them access to Pittsburgh’s Port Authority Transit throughout the city.

-

All technology needed during the program is supplied.

These recruitment processes focus specifically on addressing structural barriers to program participation, which frequently impact REM youth because of broader societal barriers that can impact their participation in STEM.

Youth Feedback

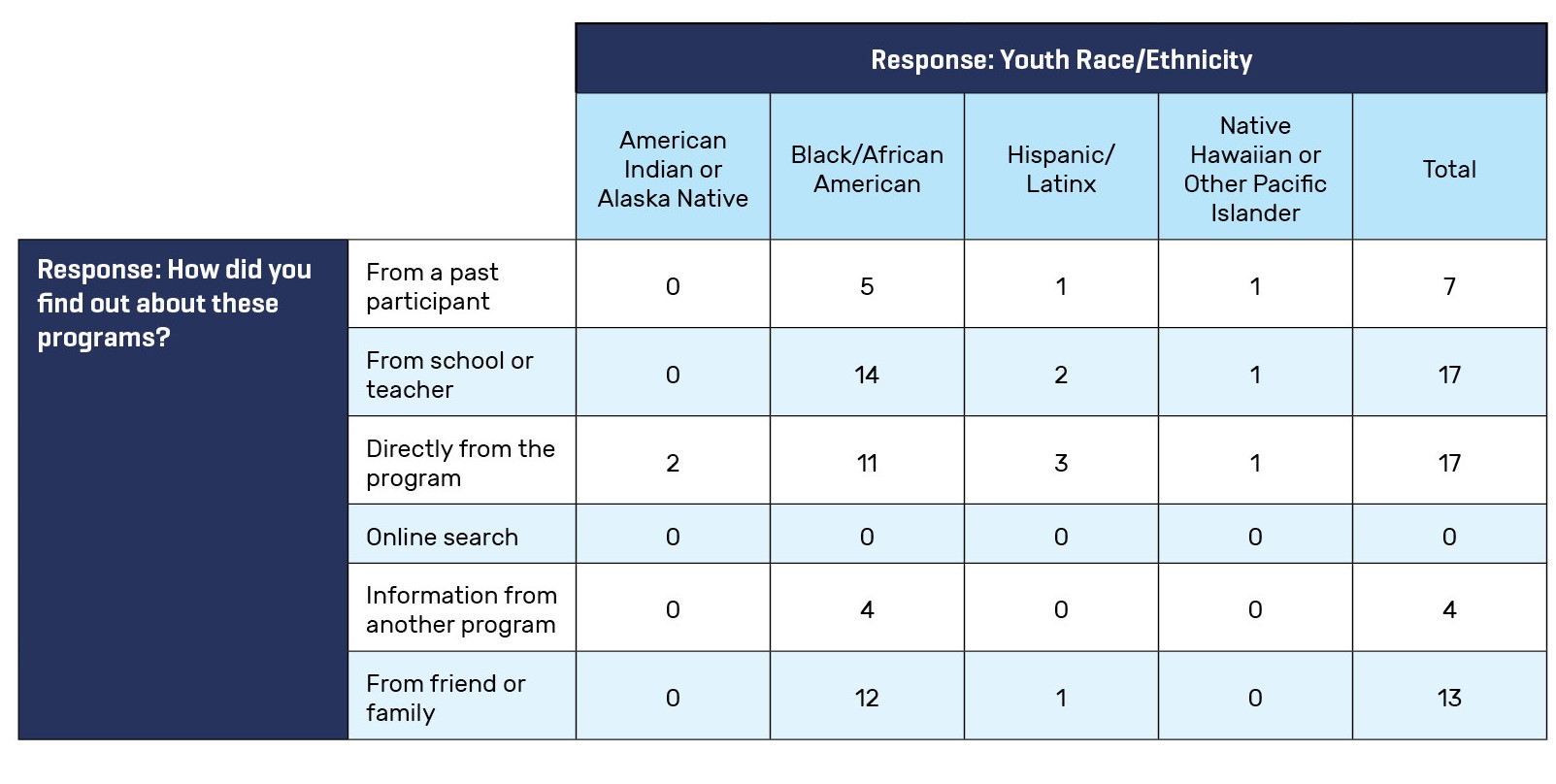

REM youth participants reinforced the importance of varied recruitment methods, especially emphasizing the importance of personal connections and networks. In a broader survey about their experiences in the precollege programs, we asked a small sample (n = 77) of youth how they found out about the program (see Table 2). Many indicated that they found out about the program from a teacher (17) or family or friend (13). Direct program outreach was also an important recruitment strategy with 17 youth finding out about the pre-college program in this way. These data, while limited, do offer some insight into more successful youth recruitment efforts.

Other Program Recruitment Practices

The four programs that are part of this study are all interested in recruiting and supporting REM youth to engage in STEM as one approach to addressing STEM inequities. To date they have had varying levels of success in this work. As demonstrated in Appendix A: Program Recruitment Methods and Materials, their recruitment techniques are varied and align with many of the practices from the literature review.

While each of the four programs are often oversubscribed, they all indicated that this was not the case when they started, and they have had and continue to face challenges specifically recruiting REM youth. To address this challenge, their recruitment practices have changed over time to improve recruitment in general while also increasing the number of applications of REM youth. These processes have changed in concert with each program’s understanding of equity and effective strategies for engaging REM youth and their families. At the same time, these programs have further developed relationships with schools and community networks. In particular, each program shared the necessity of not relying on standard forms of recruitment (which may arguably be normed toward the participation of white, middle class youth) and not expecting all families to seek the opportunities that these programs provide. Program directors pointed to developing personal connections with educators and K–12 schools, community organizations and other STEM programs, and families and communities as a particularly strong method of recruiting REM youth. In addition, they actively sought ways to get information to youth.

Limitations and Challenges

One of the primary limitations of this work is connected to additional marginalization that program recruitment focused on race and ethnicity may overlook. For instance, we are unable to address whether those who may also be marginalized due to social location, family income and employment, permanency status, or other structural challenges are participating in these precollege programs. For instance, while we know that the four programs discussed here have been able to effectively recruit REM youth broadly, there is limited understanding of who those young people are in comparison to other REM youth in the area. Other factors come into play, such as

- competing opportunities and responsibilities faced by REM youth for their time (such as work and childcare);

- familial and community relationships with the larger university (rather than just the program); and

- teacher encouragement (or lack of it) for REM students to apply to participate in these programs.

Each program may need, lend itself to, and benefit from different types of recruitment; thus, this article is exploratory but not comprehensive. It is also important to consider—though outside the scope of this article—that recruitment itself is only one small aspect of developing more equitable pathways to STEM college and careers for REM youth.

Recommendations

Our study found that REM youth and their families are attracted to programming through recruitment that used a variety of outreach techniques, demonstrated programmatic relevance and interest, and deliberately eliminated barriers to participation. While there are many ways to recruit REM youth into OSL STEM, the literature and program practices here point to the importance of

- Establishing networks and relationships—connections between IHEs and K–12 schools and other community organizations.

- Understanding and connecting to the social contexts and backgrounds of REM youth; recruitment must be connected to programming that is itself focused on young people’s culture and experiences.

- Recognizing and eliminating barriers to application and participation.

While we highlight effective methods, there are also opportunities for these programs to grow. While programs did not necessarily know the literature as they engaged in recruitment practices, they changed their strategies as they learned from experience and gained feedback from participants. The practices described here suggest deliberate actions these programs can take and also point to the importance of understanding and working within the program’s educational ecosystem. Further, they highlight the importance of programming that is focused on understanding and supporting young people’s culture and lived experiences, particularly within the specific context of individual programs.

Conclusion

Recruitment into STEM programming is a critical first step toward addressing equity in STEM college and career pathways. Drawing from literature and program practices, there are clear ways that programs can and should consider focusing their recruitment efforts for REM students. Our study highlights that developing and engaging connections and relationships; connecting to REM youths’ spaces, families, and ways of engaging in the world; and working to eliminate program barriers are effective strategies for improving programs and connecting to the youth they are trying to serve.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded as part of NSF INCLUDES DDLP Award 1744446: Diversifying Access to Urban Universities for Students in STEM Fields. This research was also funded as part of the NIH/NCI grant 5R25CA236620.

Lori Delale-O'Connor (https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd) is an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Education in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Alaine Allen is the Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Mackenzie Ball is the Director of Outreach and Alumni Engagement at the University of Pittsburgh School of Computing and Information in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. David N. Boone is the Director of Hillman Academy and an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Rebecca Gonda is the Director of Outreach and a visiting lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh Department Biological Sciences in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Jennifer Iriti is a research scientist and Co-Director of Partners for Network Improvement at the University of Pittsburgh Learning Research and Development Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Alison Slinskey Legg is the Director of the Broadening Equity in STEM Center and a Senior Lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh Department of Biological Sciences in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

citation: Delale-O'Connor, L., A. Allen, M. Ball, D. N. Boone, R. Gonda, J. Iriti, and A. Slinskey Legg. 2021. Broadening equity through recruitment: Pre-college STEM program recruitment in literature and practice. Connected Science Learning 3 (6). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-november-december-2021/broadening-equity

Advocacy Equity Interdisciplinary STEM High School Informal Education