Case Study

The Role of Question-Asking in Mentoring Undergraduate Research

Journal of College Science Teaching—January/February 2023 (Volume 52, Issue 3)

By Sara L. Johnson and George M. Bodner

Undergraduate research is a high-impact educational practice for which effective mentoring has been identified as a key factor in determining its success. Some researchers have argued that effective mentors help increase students’ independence and ownership of the research project. This case study used conversation analysis to examine recorded interactions between an early-career postdoctoral mentor and a first-year undergraduate research student within the context of “mentoring by questioning” in a biochemistry research group. The study was based on three guiding research questions: What norms of discourse frame conversations about independence and ownership of research? How are the norms of discourse established? What impact do these conversations have on the undergraduate research experience? Analysis of the data collected in this study suggested three ways in which the mentor used the discursive tool of question-asking to guide conversations with the undergraduate research student: encouraging scientific observations, shifting responsibility, and encouraging critical thinking.

Undergraduate research (UR) has been identified as a high-impact educational practice that “can enhance student engagement and increase student success” (Kuh, 2008). While many factors contribute to a successful UR experience, at least one factor remains constant: effective mentorship (Kuh, 2008; Laursen et al., 2010; National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, 1997; Osborn & Karukstis, 2009; Wenzel, 1997). Regardless of the discipline, the benefits students gain from participating in UR hinge on the quality of mentoring they receive (Bowman & Stage, 2002; Hensel, 2012; Ishiyama, 2007; Jones & Davis, 2014; Linn et al., 2015; Mekolichick & Gibbs, 2012; National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, 1997; Pfund et al., 2006).

A variety of resources exist to provide guidance to those seeking to develop their skills as mentors (Shanahan et al., 2015; Temple et al., 2019; Vandermass-Peeler et al., 2018). Shanahan and colleagues, for example, have argued that an effective mentor is one who helps increase students’ independence and ownership of research projects over time by working to improve their confidence, encouraging them to provide opinions about the research, and giving them shared power on a project. It may be difficult, however, for mentors to see how these suggestions translate into concrete actions they might take in their own research group. What does a mentor say, for example, to increase confidence? How should a mentor respond if a student is hesitant to share responsibility on a project?

We were motivated by questions such as these to take a closer look at how mentors and students engage in research together in the laboratory. Specifically, we were interested in the conversations between mentors and students that related to independence and ownership of research because increasing student ownership of research over time is a salient practice of effective UR mentors (Shanahan et al., 2015). We used a conversation-analysis case study approach to explore the structure of conversations between mentors and undergraduate research students in biochemistry laboratories (Johnson, 2017). We purposefully selected cases, made up of a mentor-and-student pair, to obtain a diverse sample in terms of research experience (Laursen et al., 2010). Each case included either a novice or an experienced undergraduate researcher being mentored by a graduate student or a postgraduate or faculty mentor. Our research was guided by the following questions:

- What norms of discourse frame conversations about independence and ownership of research?

- How are the norms of discourse established?

- What impact do these conversations have on the UR experience?

We collected data in the forms of video-recorded observations in research laboratories, audio-recorded individual interviews, and artifacts (e.g., laboratory protocols) for each case. By organizing conversations into activity frameworks, we were able to investigate conversations about independence and ownership at multiple levels of granularity (Clayman & Gill, 2011) within and across cases (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). We defined activity frameworks as stretches of interaction that focused on singular actions (e.g., engaging in research). We used individual interviews and artifacts to enrich our understanding of the video-recorded conversations and explore the impact these conversations had on the UR experience.

Our approach provided a deeper understanding of the role that question-asking can play in increasing student independence and ownership of research. Although the importance of asking questions is a well-documented feature of the typical classroom environment (Goodman & Berntson, 2000; Vogler, 2005, 2008), its role in UR mentorship—and the diversity of ways questions can be used to develop independent researchers—has yet to be explored. In this article, we explore the role that question-asking played in one of our cases, which included a novice undergraduate researcher, Simon, being mentored by Mia, a postgraduate mentor.

All of our cases demonstrated effective mentoring strategies, but we chose to focus on this case because of the unique discursive mentoring strategy enacted by Mia and the positive impact her question-asking strategy had on Simon’s development as an independent researcher. Our aim with this case study approach is to provide an in-depth description and analysis of the specific discursive practice of question-asking and report on the benefits of this practice observed without our case (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Our exploration of Mia’s use of question-asking provides concrete examples of how a mentor found ways to have a positive effect on one UR student. Although our study was set within the context of a biochemistry UR opportunity, we believe the findings we present in this article are relevant to a variety of disciplines and mentoring contexts.

Our study

Participants

Mia held a PhD in chemistry and was in her first year in a postdoctoral position. Mia had worked with undergraduates in the laboratory before, but her past experiences had been with older students, often in the last year of their undergraduate degrees. She considered Simon to be her first novice researcher.

Simon was a driven and academically successful biochemistry major. Although still in his first year, Simon was a sophomore based on academic credits. He was enrolled in organic chemistry, a course normally taken by biochemistry majors in their second year. Simon and Mia began working together after Simon approached Mia’s supervisor about UR opportunities. When we began observing the pair, Simon had been working with Mia for about a month on an enzymology project.

Data collection

Our primary form of data collection was video-recorded observations in the laboratory (from Simon’s perspective). For the duration of observations, Simon wore a Drift Ghost-S Professional HD Action Camera mounted to a headband, as well as a lapel microphone. This arrangement was developed during a pilot study to ensure high-quality data collection with minimal participant discomfort. This setup allowed us to hear and see details of what Simon was doing (e.g., reading a protocol, preparing reagents, writing notes) and provided context for our interpretation of conversations. We used this method to observe Mia and Simon working together for approximately 10 hours over 3 months.

Individual interviews were conducted with Simon and Mia midway through the laboratory observations. These semistructured interviews followed a stimulated-recall design that prompted Simon and Mia to reflect on their conversations and experiences together (Lyle, 2003). The interview protocol utilized both video clips and reflective questions to provide data that addressed our research questions. We selected video clips of conversations for use in the interviews based on the following criteria: Both Mia and Simon participated in the conversation, the conversation met our definition of an activity framework, and the conversation was representative of our observations.

We also collected artifacts that helped inform us about Mia and Simon’s research and their conversations. These included research articles, images from research notebooks, published protocols, and research group web pages.

Data analysis

We approached analysis of our data from a hermeneutical perspective. Hermeneutic studies focus on interpretation of texts as a way of understanding (Gadamer, 1976, 1985; Laverty, 2003; Patton, 2002; van Manen, 1990). The goal of hermeneutic studies is not to generalize across audiences or reveal the truth of participants. Rather, interpretation of text is accepted to be subjective and specific to both the context in which the text was created and the context in which the researcher interprets it. In addition to acknowledging the perspective a researcher brings to interpretation of texts, hermeneutic studies recognize the dynamic nature of a researcher’s perspective. A researcher may begin approaching interpretation in one way, but through repeated interactions with texts, their understanding of the meaning of the texts may change. This practice—where the interpretation of the text informs perspective and therefore interpretations of future analysis of texts—is referred to as the hermeneutic cycle and was a core component of our analysis.

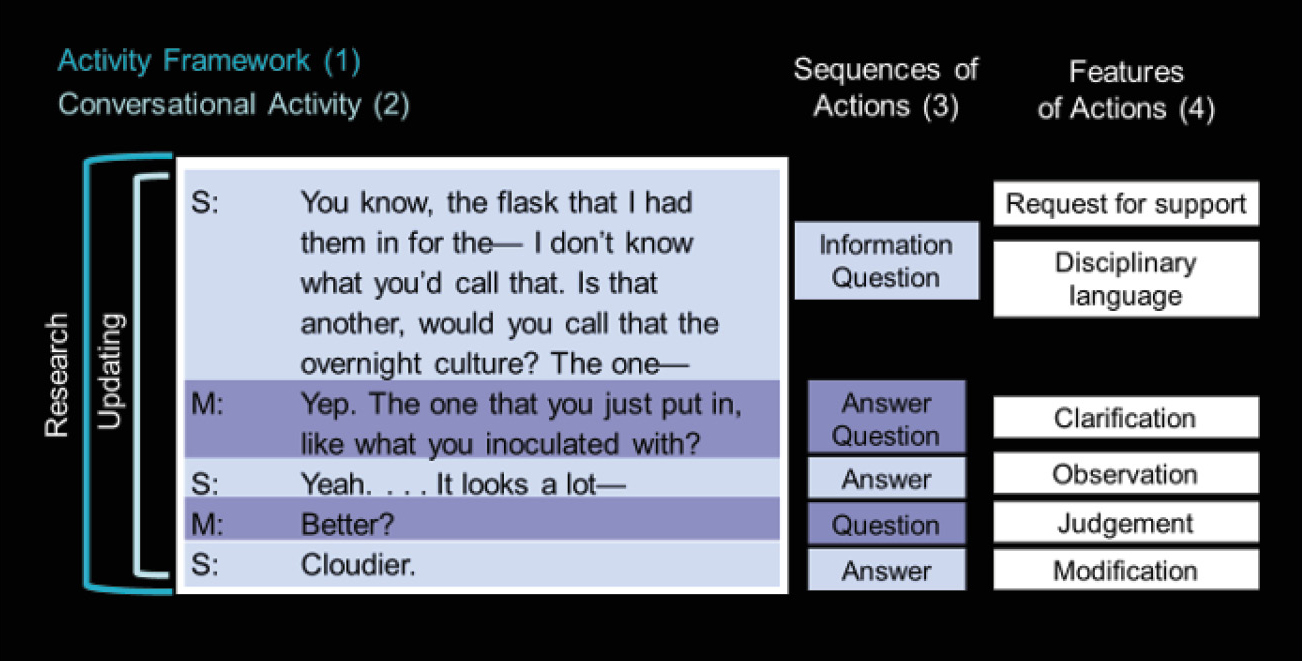

Our analysis of observational data began during transcription. All audio data were transcribed and then coded using an inductive approach. We began the analysis by identifying activity frameworks indicated by a change in topic or focus of a conversation (Clayman & Gill, 2011). Discrete activities were identified within the activity frameworks and further parsed into individual activities. We identified individual actions and sequences of actions for each activity framework and characterized the features mobilized within these actions. In our finest-grain analysis, we explored specific features of Mia’s and Simon’s individual utterances. This analysis was informed by Gee’s discourse analysis toolkit (Gee, 2011a, 2011b). See Figure 1 for an example of this analytical scheme.

Example of the analysis of a conversational activity.

Mentoring by questioning

Analysis of the conversational activities suggested three ways that Mia used the discursive tool of question-asking to guide conversations with Simon within the general category of mentoring by questioning: encouraging scientific observations, shifting responsibility, and encouraging critical thinking. Each practice is presented individually, although Mia regularly wove together combinations of discursive tools during a conversation.

In The Savage Mind, Lévi-Strauss (1962) used the term bricolage to describe the skill of recombining pre-existing tools in new, creative ways and bricoleur to define individuals who can make do with whatever is at hand. Just as bricoleurs make use of the diversity of tools available to them in their creations, Mia regularly wove together combinations of discursive tools during conversations with Simon. Our intent in isolating and focusing on her various uses of questions is to provide multiple examples that can serve as inspiration for mentors seeking to expand their own discursive toolboxes to encourage student independence and ownership of research.

Encouraging scientific observations

In our first observations, we watched Simon learn new techniques from Mia. When learning a new task, Simon either worked in parallel with Mia, or they took turns performing a particular task. During these activities, Mia used questions to encourage and improve Simon’s observational skills. (Utterances such as “um” and “uh” have been edited out of quotes.)

Mia: All right, so (Mia moves sample in front of Simon.), does it look like color difference to you? (Mia makes eye contact with Simon.)

Simon: It looks lighter, I think, a little bit.

Mia: Does it look like, OK, so we’re going to judge beige.

Simon: OK.

Mia: So originally it looked like a pinky, beige. (Mia gestures to sample.)

Simon: Yeah.

Mia: I want to say and this looks more like—it looks darker.

Simon: OK.

Mia: And maybe not as opaque; it feels a little more watery.

Simon: Yeah.

Mia: Does it to you?

Simon: Yeah.

Mia: OK, and so, you’ll be able to see it better, but I think this is a better lysis, just by looking at the color.

Mia often asked questions that drew Simon’s attention to specific aspects of a technique, such as the way a sample looked, smelled, or felt. When directing Simon’s attention to an observation, Mia used questions that encouraged Simon to give his own observation as a novice before she stated hers as an expert in the field. In the previous example, Simon’s lack of experience with the technique resulted in his description lacking adequate detail, so Mia provided additional information that could help Simon enrich his observational skills. She then asked her question again, reiterating the importance of Simon being able to see the difference in color for himself when he used this technique in the future.

Shifting responsibility

As Simon became familiar with a technique, Mia used questions to shift responsibility for tasks onto him. Mia’s questions in conversations like these served two purposes. First, they created an opportunity where she could explore Simon’s recollection and comfort in executing a task, which provided an opportunity for her to give personal support if Simon needed it. Second, Mia’s questions communicated Simon’s responsibilities in the laboratory; he was responsible for recalling laboratory techniques.

Mia: All right, so it’s going to be the same as—remember this time? (Mia places copy of protocol in front of Simon.)

Simon: Yeah. (Simon looks at protocol.)

Mia: When we lysed it. (Mia points at top of protocol.)

Simon: With a buffer, yeah.

Mia: Uh-huh. And so do you remember, like, what we did?

Simon: First we made the buffer—or we got our ice and put the pellet on the ice to thaw it.

Mia: Mmm-hmm.

Simon: And then we made the buffer while it was thawing and we had to get the, I think (Simon looks at protocol.), some of this was already made. (Simon points at protocol.)

Mia: Yep.

Simon: Yeah. And then we had to add the lysozyme, DNAse, and DTT.

Mia: All right, so we can do that. And this time I’ll let you lead the way.

Simon: OK.

Mia: And I’ll just follow you and watch you.

Simon: OK.

Mia: And if you need help, then I’ll tell you what to do.

If Simon’s response seemed unsatisfactory, Mia followed up with new questions that were intended to provide additional information about a task. However, by providing the information in the form of a question, Mia was still able to hold to the expectation that Simon would fill in missing information.

Encouraging critical thinking

In addition to focusing questions on what Simon was doing, Mia also used questions to focus on why Simon was doing specific tasks. We observed Mia responding with questions to encourage critical thinking in two types of situations. In early observations, Mia asked these questions while she was teaching Simon new techniques. In later observations, we noted that if Simon made a mistake, Mia would correct him, then continue the conversation with a question focusing on why the mistake mattered.

Mia: And so why do you do the on and off?

Simon: (Simon looks at laboratory notebook.) They go 6 seconds on to actually do the lysing and then it goes 9 seconds off, so, does it let it settle back down? So then it doesn’t create bubbles or … (Simon looks at Mia.)

Mia: Keep going.

Simon: So it settles back down. (Simon looks at his laboratory notebook.) So is it like, because if it like consistently for the whole 15 minutes then, wouldn’t it, like it, just be completely destroyed? (Simon looks at Mia.)

Mia: Why?

Simon: In the protein, because (Simon looks at his laboratory notebook.) it has like no time to refold? (Simon looks at Mia.) Not refold (Simon looks at his laboratory notebook.), but I don’t know.

Mia: It has to do with the type of beaker it’s in.

Simon: Oh. Would it—oh, would it get too hot? (Simon looks at Mia.) Doesn’t have enough time to cool back down.

Mia: Correct, so we’ve gotta give it some time to cool back down.

Simon: Because metal’s a really good conductor of heat.

Mia’s questions could have been interpreted as attempts to check Simon’s understanding of a task and, thus, shift more responsibility onto him. However, based on our interviews with Mia and Simon, we considered them as a separate way of using questions because they were impromptu conversations about the scientific reasons behind specific steps. Mia had not previously explained the concepts behind the tasks; her questions were an effort to have Simon consider the reasoning behind completing the task in a particular way.

Sharing authority

As might be expected for a novice researcher, it was common for Simon to not know answers to Mia’s questions or to need reminders about techniques. In later observations, Simon approached Mia for refreshers of tasks he was now completing alone. In these instances, we interpreted Simon’s treatment of Mia as an authority figure who represented an expert resource. Rather than answering Simon’s requests directly, Mia regularly responded with questions that directed his attention to other resources and challenged his treatment of her as the sole authority figure on their project. Two resources onto which Mia regularly shifted attention by asking questions were Simon’s research notebook and established technique protocols she had helped him collect.

Mia: Do you have your Abcam—that Abcam [protocol]? (Mia picks up Simon’s laboratory notebook.)

Simon: I think it’s in the opening on the left.

Mia: Just let me—oh, here it is. So then it will be easier to follow along. (Mia places protocol in front of Simon.)

Simon: OK.

Mia: All right, so, all of this (Mia gestures to protocol.) is like part of the western blotting experiment, literally, is just this part. (Mia points to specific place on the page.)

Simon: That part, yeah.

Mia: (Mia reads aloud.) “Transfer proteins and staining.”

Simon: Mmm-hmm.

Mia: The other part is just in preparation for that.

Simon: OK.

Mia: But what I’ve known from a western blot is—you—not even the transfer just the staining so.

Simon: Mmm-hmm.

Mia: But here, so we did this, now we’re here. (Mia points to specific place on the page.) So, here’s the TBS 10X and then—you—or TBST. And you add the Tween 20 after you dilute it.

Simon: OK.

When Mia redirected Simon’s attention to outside resources, she demonstrated how to use those resources to find the answer to his question. Sometimes, as in the previous example, this was done through reading the protocol. She often used questions to guide Simon through using his notebook and protocols to find answers to his questions.

Mia: So read the instructions.

Simon: OK. (Simon begins to read.)

Mia: And see if that helps you—I’ll tell you the volumes to add, but does it help you with what you need to do?

Simon: (Simon reads for 2 seconds.) Yeah—I think.

Mia: So, if you took those directions, you could follow them and prepare your samples and run a gel?

Simon: No. (Simon laughs.)

Mia: What—what do you need other than that?

Simon: (Simon flips page in protocol.) I would need, I don’t really know how to (Simon reads aloud.) “Heat it to 95 degrees for 1 minute.” And then …

Mia: What else? (8 second pause) It’s not a trick question.

Simon: (Simon laughs) Besides that, I’m not really sure, so we’re adding these to micro tubes, right? Like OK.

Mia: Mm-hmm.

Simon: So, I just would need to be able to find DDT.

Mia: OK.

Simon: And the gel that I had.

Mia: Then go through the whole process in your head and see if there’s anything else, ’cause I know you’ve done it a few times, so just try to imagine it.

Mia continually emphasized the importance of Simon’s laboratory notebook and technique protocols during their research. From our very first observation, we saw Mia providing Simon with copies of protocols and teaching him how to make high-quality records in his laboratory book. Despite these efforts, Simon still tended to defer to Mia when unsure how to proceed. This is understandable; as a postdoctoral researcher, Mia had far more experience. However, this made Simon’s productivity dependent on Mia’s availability and created a dynamic in which Mia acted as the owner of their shared research. Mia’s questions provided a discursive tool by which she tried to shift attention away from herself as the authority figure and onto resources that would ultimately support Simon in his growth as an independent member of the research team.

Impact on Simon

Simon and Mia applied for funding that would allow him to work in the laboratory the summer after our observations. The project was designed so that Simon could complete it independently, using techniques he had learned over the course of the semester. To achieve this independence, though, Simon would have to be comfortable working by himself. In an interview, Mia noted that a major barrier to achieving this goal was Simon’s constant need for assurance:

Well, he is still trying to make sure he is doing everything right, so even though I know he knows what to do, he’ll still ask me, like, I should do this, right? And so trying to get him away from getting the reassurance and so he is … He is slowly—I said—well, I’ll ask him what does he think? And then now I’ve got to, “You tell me.” And then I will let you do it and then if you mess up, you start over again. So, I’m trying to wean him off of the reassurance except on the important things like making sure the centrifuge is screwed down properly.

Mia deliberately used question-asking to address Simon’s need for assurance to prepare him for more independent work in the future. We were interested in Simon’s perspective on this shift in mentoring and asked him to reflect on this change and its impact on his experience during our interview. He said,

She’s trying to get me more independent. ... [T]hat way, this summer and in the future, I can be on my own and she can do her own thing and I can assist her more without having her to hold my hand. ... She used to just explain to me everything, but now I’ll ask a question and she’ll throw it right back at me. She’s like, why do you think? Well, I don’t know, and then she forces me to think through it and that helps me get better. Which it kind of stinks sometimes because I don’t know the answers. But ... it helps me learn when she’s tough on me like that.

Although Mia’s method of questioning Simon was not always comfortable, it was effective. Simon was aware of the need to work independently and saw the benefit of Mia using questions to encourage his growth in this way.

Discussion

Throughout our observations of the interactions between Mia and Simon, we identified question-asking as the primary norm that framed conversations about independence and ownership of research. Although these conversations were often established by Mia, we also observed Mia initiate these conversations in response to Simon’s questions. In this way, Mia used questions as a discursive tool to shift the topic of the conversation from a request from Simon for personal support to a conversation about developing Simon’s independence as a researcher (Laursen et al., 2010).

These conversations required effort from both participants because Simon did not always have an answer to Mia’s questions, and Mia spent a significant amount of time rephrasing questions to guide Simon in his own discovery of the answer. We concluded that the effectiveness of these methods made them worth the effort. We base this conclusion on the increase in Simon’s independence and his ownership of the pair’s research. Over the course of our observations, Simon asked fewer logistical questions, referenced his notebook and protocols more often, and worked alone more often.

Although the UR experience differs from other forms of instruction (Vandermass-Peeler et al., 2018), with significantly different expected outcomes (Laursen et al., 2010), asking good questions is still important as a way to shape students’ construction of knowledge (Bodner, 1986). We have therefore characterized some of the ways a mentor can use the discursive tool of asking questions to encourage independence and ownership of research (see Figure 2). Although we use interactions between Mia and Simon as examples, we believe our recommendations cross disciplinary boundaries and can provide guidance to mentors working with students in a variety of research settings.

Recommendations for mentors.

1. Communicate your intentions.

Mia used questions as a tool to reinforce the expectations about Simon’s independence and ownership that she had first made clear in her initial meeting with Simon. When establishing expectations for research experiences with students, include a conversation about how the practice of question-asking will support your shared goals.

2. Consider what you say that could be asked.

Answering a question or giving instructions may be an efficient method of communication, but that does not mean it is the most effective method. Reflect on conversations you have had with students you have mentored, and consider how you could rephrase statements into questions.

3. Don’t be afraid to ask “simple” questions.

Experts may take for granted much of the knowledge and practices that are the foundation of their field (Coulon, 1995). This may lead to overestimates of a novice researcher’s knowledge. Do not be afraid to ask simple questions: What does this look like to you? Why do you think that occurred? Why do you think we are doing this?

4. Be persistent.

If asking questions in this manner is new to you or your student, you can expect difficulties. Anticipate these difficulties and consider rephrasing the question or separating it into smaller leading questions that will guide your student in constructing an answer.

Sara L. Johnson (sjohnson34@una.edu) is an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Physics at the University of North Alabama in Florence, Alabama. George M. Bodner was the Arthur E. Kelly Distinguished Professor of Chemistry in the Department of Chemistry at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

Inquiry Preservice Science Education Research Teacher Preparation