Feature

The Survival Games

Linking science and science fiction to better understand the realities of biomes, fitness, and climate change

The Science Teacher—January/February 2021 (Volume 88, Issue 3)

By Gabriela E. Rodriguez, Zainab Shoda, Hannah R. Assour, Vanessa Fischer, and Janelle M. Bailey

In a world with an ever-changing climate that causes dozens of extinctions a day (Center for Biological Diversity n.d.), it is more crucial than ever to explore the ways in which ecosystem changes can affect organisms’ fitness. The project described in this article guides students through learning about the many biomes on our planet, the organisms that live there, and what makes them fit for their environment. Along with this, the idea of structure and function is reinforced as students think critically about how biological structures provide organisms with various functions. The project also challenges them to consider how these organisms will fare in the face of climate change.

The use of project-based instruction gives students ownership of their learning, affords more voice and choice, and provides more opportunity for active learning (Larmer, Ross, and Mergendollar 2017). Students engaged in project-based learning, especially students in urban schools, have been shown to achieve higher scores in both science content and practice skills (Geier et al. 2008). Additionally, combining science content with science fiction from pop culture helps to promote student engagement. The more students are engaged with a lesson, the more they will learn from it.

We used The Hunger Games (Collins 2009) in the classroom solely as a cultural reference to make the science content more interesting and engaging for students. But there is also potential to make this a cross-curricular activity if students read The Hunger Games ahead of this project. If students do not read the book or have not seen the movie (Ross 2012), it is important to give them some background and context, such as highlighting that The Hunger Games is fictional and we are simply using it as a mode of exploring science concepts. One portion of the activity requires students to create their own organism, informed by real organisms in their biome. This choice—as opposed to having students work with existing, real-world organisms—was made to allow students’ creativity, another hallmark of project-based instruction (Larmer, Ross, and Mergendollar 2017).

The Activity

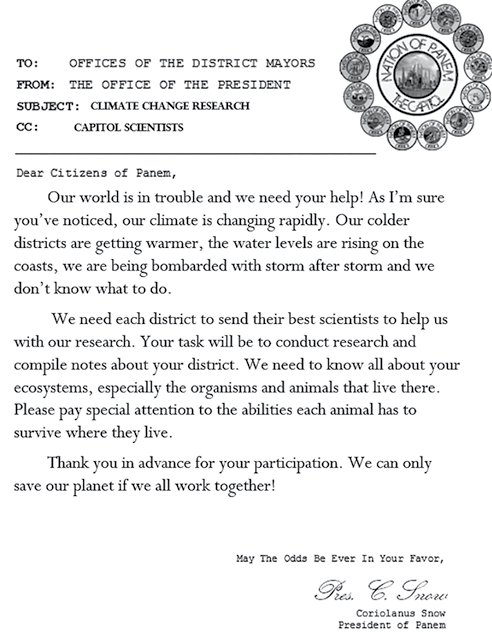

To start the activity, students receive a letter from the capitol (Figure 1) that introduces both the project’s connection to The Hunger Games and its focus on biomes, organisms, and fitness. We then split students into groups of four, with district numbers and corresponding biomes. Next, a brief mini lesson on biomes introduces students to the topic and refreshes their memory before diving into their research project. The mini lesson covers what biomes are, the differences between land and aquatic biomes, and how biomes vary all over the world.

Letter from the Capitol

Materials

Throughout the project, students will need:

- Laptops, tablets, or computers with internet access

- At least two websites, given as examples of reputable sources for research (see “On the Web”)

- Various worksheets to guide students through each step of the activity

- Large paper and markers

Part 1: Research

Provide students with laptops/tablets, a webquest style packet, and the links to two websites to get them started on their research. Ask students to complete the first part of the packet, which asks them guiding questions about their specific biome. Remind students that they may use additional resources beyond the two provided websites, but that they should be sure resources are reputable and that they can and should ask a teacher if they are not sure about a resource they found. Check in with students to make sure each group has completed the first section; students can share out something interesting they learned about their biome.

Next, redirect student attention to the plants and animals that live in their biome. The second part of the packet will guide students through asking questions about the organisms, special traits they have, and how these traits help them survive in their biome. Again, check in with students to make sure each group has finished the section.

Finally, facilitate a student discussion on the research they just completed, and lead into another mini lesson, teaching the concept of biological fitness. Depending upon the depth of research you want the students to find, this part should take about one to two class periods.

Part 2: Animal creation

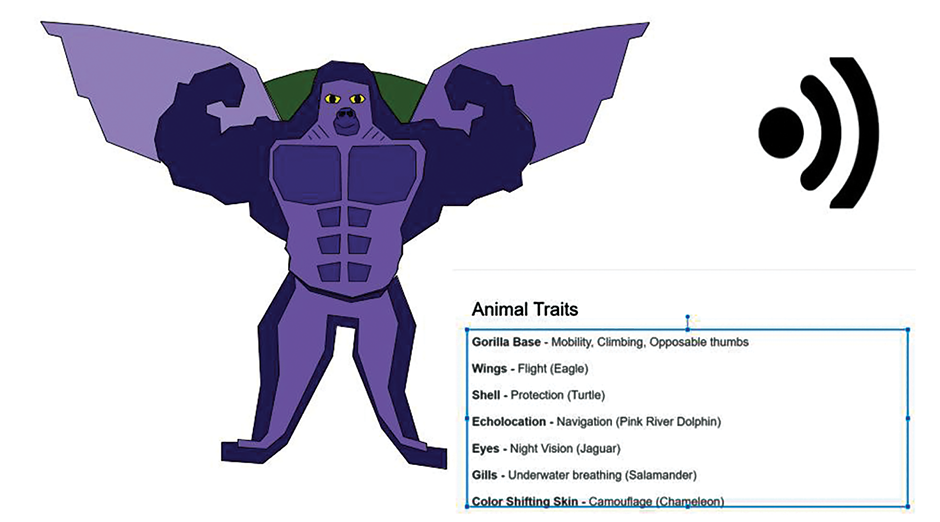

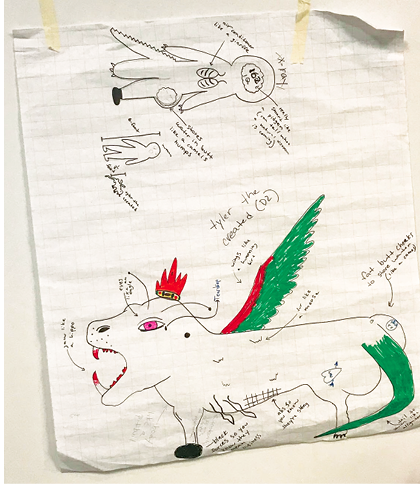

At the start of the next class, lead students in a discussion of what was accomplished in Part 1 and have them refer back to their packets. The next task involves groups creating a fictional creature that lives in their district’s biome. Give students directions for creating their animals along with a worksheet to help organize their traits and emphasize the importance of using only real traits found in real animals, and only those from their assigned biome. Provide students with uninterrupted time to choose traits and design their animals.

Check in with groups periodically, and when students seem ready, hand out poster paper and markers. Some groups may choose to draw their organisms digitally instead (Figures 2 and 3). We required students to include a minimum of five traits, describe the benefits of each, and cite the animal in which they originally found the trait. This part should take about one to two class periods.

Student animal creation.

Student poster.

Part 3: The Survival Games

Give students some time to finish up and review their organisms at the beginning of the next class. After a few minutes, explain the rules of The Survival Games. Present climate change scenarios on the board along with traits that organisms could have that would either help or hurt (e.g., if the scenario was a forest fire, having wings would help animals escape, whereas living in trees would hurt an animal’s chance of survival).

Because students will have chosen traits from organisms found in their biomes, each group will be affected by these climate change scenarios differently. It is also important to note that biomes will be affected differently by the various climate change scenarios. At this point it would be worthwhile to remind students that their organisms are not adapting; instead, they have existing traits that enable them to survive in new situations.

Additionally, it is crucial to have a predetermined point system for this part of the activity. We suggest having all groups start with 50 points, with each climate change scenario resulting in students gaining or losing 5–10 points. The exact point value could be determined by the severity of the scenario. If a team drops to 0 points, their organism would be considered extinct and they are eliminated from the game. Whichever team has the most points at the end of the game is declared the winner of The Survival Games, as their animal was best able to survive climate change.

It is also important to note that students will try to argue the helpfulness of additional traits, so a clear system is needed to make these decisions, but is at the discretion of the teacher. One possible system is to have all other groups quickly vote on whether or not the proposed trait would truly help the organism survive and should be accepted. This part of the project should take about one class period.

It could also be beneficial to guide students in a discussion about climate change after going through The Survival Games. Ask students probing questions to get them thinking about how climate change is related to their group’s assigned biome, and ecosystems at large. This discussion should hit on the idea that climate change is affecting organisms from all biomes in a variety of ways. This should help students tie all parts of the lesson together and recognize why climate change is an important issue.

Part 4: Presentations

After the class has gone through The Survival Games, give students time to reflect on their animals’ outcomes. Then give students directions for their presentations. Each group should present their organism, the traits they included and why they were included, the traits that helped them most in the games, the climate change scenario that most affected them, and a trait they would add if they could go back. Each group member should participate in the presentation, and presentations should only be about five minutes each. At the end of each presentation, students can ask each other questions about their animals and the choices they made while creating them. Preparation and presentations should take one to two class periods, depending on class size.

Assessment

After completing this project, students should be able to:

- Name the aquatic and terrestrial biomes.

- Describe, in detail, the ecosystems of their researched biome.

- Give examples of (real) organisms in each biome.

- Define fitness and apply it to their created organism.

- Create a visual and/or textual representation of their created organism.

- Explain how certain aspects of climate change affect organisms in different biomes.

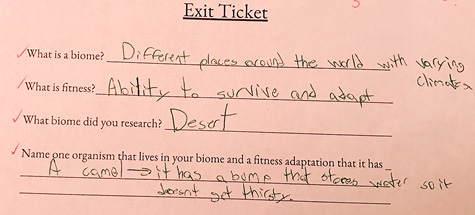

This project has several forms of formative assessment. The first is the packet that students complete. Their responses throughout the packet will demonstrate how much they were learning during the research activity. The second is an exit ticket given at the end of Part 1, asking students about their biome and animals that live there (Figure 4). This shows how much information students retained and understood during their research. Another formative assessment is the animals the students create. In developing their animals, students demonstrate their understanding of fitness and how traits affect fitness.

In addition to these formative assessments, student presentations serve as a summative assessment. All group members are responsible for sharing part of the presentation so teachers can hear from each student. Additionally, this provides a space for students not only to share their work, but the thinking that went into it, and their reflections. These aspects of the assignment allow students to really show what they have learned throughout the course of the project. The rubric we used is provided (see “On the web”). We broke assessment into four main parts: the research done on the specific biome, the creation of the organism following the given criteria, the final oral presentation, and self/peer assessments.

Exit ticket

Teacher feedback

We originally taught this lesson to a group of 12 ninth-grade students in a Philadelphia magnet school that focuses on project-based instruction. Though initially planned for upward of 25 students, we easily adapted the lesson for a smaller class size, and could have adapted it for a larger class as well. Giving students a set amount of time to work on each section helped to keep students on task and learn how to manage their time appropriately.

There are many ways that this lesson could be differentiated to fit the needs of students. Teachers could use targeted grouping so students are best able to support each other in learning. Additional research time or guidance could be provided, as well as resources in a variety of languages. The components of animal creation and presentation could also be adapted by having students include fewer traits or explaining any climate change scenario, instead of the one that most affected their organism.

Throughout the course of the lesson, teachers overheard a great deal of unprompted student discussion about not only the creative aspect of the project, but the science content as well. It was also evident that students had truly been thinking about the content during presentations, because student explanations and reflections were detailed and thoughtful. The biggest issue teachers had was scoring during the game, but this issue could be solved with additional planning beforehand, to ensure that there is a clear set of rules and that all instructors (if there are more than one) are on the same page. Additionally, students said that they liked the lesson and thought that it was a lot more fun than they had expected it to be.

It is important to note that this project should fit into a larger unit on evolution and ecology. This placement would be crucial in ensuring that students have an understanding that evolutionary adaptation does not occur in individual organisms, but rather in species across many generations. There is potential for misconception here, so it is important to address this concept with students and explain that while organisms’ traits contribute to their fitness, organisms do not develop these traits as a way to adapt to their environment over the course of their lifetime.

Conclusion

To drive home our core concepts, we used project-based learning to connect biomes, biological fitness, and climate change in a hands-on and engaging way. Students often simply memorize facts about the impacts of climate change on ecosystems and fitness, but this project gives them the opportunity to experience this phenomenon firsthand. When applied in a fictional and theoretical world, students are able to understand the concepts and apply them to real-world situations in future class and life settings. This project not only lets students be creative when developing their animals, but forces them to think critically and formulate arguments about their animals’ traits during The Survival Games. Throughout the project, students were never just given answers, but rather the tools to find answers themselves. Through inquiry, investigation, and hands-on application, students were able to learn important ecology concepts that they will take with them into the world. ■

On The Web

Webquest starting websites

Gabriela E. Rodriguez (tug40859@temple.edu), Zainab Shoda, Hannah R. Assour, and Vanessa Fischer were all preservice teachers at Temple University in Philadelphia, PA at the time they taught this lesson. Gabbi is now a science teacher at Murrell Dobbins CTE High School in Philadelphia, PA; Zainab is a biological technician at Merck; Hannah is a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; and Vanessa is a physician assistant student at Chatham University. Janelle M. Bailey is an Assistant Professor of Science Education at Temple University.

Biology Climate Change Environmental Science Inquiry Life Science Teaching Strategies Middle School High School Grades 9-12