Feature

Shake A Bush

Discovering nature on your school grounds

Science and Children—April/May 2020 (Volume 57, Issue 8)

By Tammy D. Lee, Melissa Dowland, Megan Davis, Lauren Brewington, and Lauren Pearce

I like to play indoors better ’cause that’s where all the electrical outlets are. A fourth-grade student. (p. 10)

Almost everyone who cares deeply about the outdoors can identify a particular place where contact occurred…. Robert Michael Pyle. (p. 173)

Our children no longer learn how to read the great Book of Nature from their own direct experience or how to interact creatively with the seasonal transformations of the planet. They seldom learn where their water comes from or where it goes. Wendell Berry. (p. 133)

These chapter epigraphs from The Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv (2005) illustrate the importance of connecting teachers and students with the natural world. Our state museum’s mission is to illuminate the natural world and inspire its conservation. Educational specialists from the museum achieve this mission by helping educators across the state use and enhance the natural resources available on their school grounds as a teaching tool. The following lesson is one example of the museum’s partnership with a university science educator to expose teachers and students to outdoor-based learning as a context for studying systems in elementary science.

Two educational specialists from the museum, two elementary science teachers from a local district, and an assistant professor in science education teamed up to create an outdoor learning lab for fifth-grade students at a local elementary school. The 5E learning cycle (Bybee 1997) was completed in two days, emphasizing the Next Generation Science Standards’ performance expectation 5-LS2-1: Develop a model to describe the movement of matter among plants, animals, decomposers, and the environment.

Designating the Outdoor Learning Lab

Typical school campus landscapes often leave much to be desired in terms of a natural environment. While keeping plantings to a minimum on school grounds reduces the burden on maintenance staff, it also means that many teachers may overlook their school grounds as a natural ecosystem waiting to be explored. The location selected for this lesson was the only area on this school’s campus that had any substantial plant life. This school was chosen because we wanted to support two beginning teachers in overcoming this obstacle for teaching natural sciences outdoors on a somewhat barren campus. The selected area had two crepe myrtle shrubs (non-native) and three small dogwood trees (native). (For this lesson we referred to the crepe myrtle as a shrub due to its small size and how it had been trimmed.) The individual tree or shrub defined the system of study, allowing for a manageable outdoor learning lab. The microhabitat within and under a tree, bush, or shrub illustrates the components, levels, and interactions of the larger ecosystem, allowing it to be used as a comparison model system.

Engage

The engage portion of the lesson began with a class discussion of outdoor areas on the school campus. Students were asked, “Can we find a natural area (e.g., trees, shrubs, and stream) on campus to study?” Students responded with mixed reactions, some stating that they had never seen many trees at the school. The class was led on a walk to locate possible natural areas to investigate. Students found the predetermined area on our walk and agreed to make this the outdoor learning lab. Many of the students were surprised to find the area. As one student commented, “I walk past here every day on my way to the buses, but I am usually so busy walking that I have never noticed the trees.”

With the location determined, students were grouped and assigned to either the dogwood tree or the crepe myrtle shrub as their individual outdoor learning lab. Students were asked to create a list of living and non-living things that they would find on, around, and below their plant. Students provided the following predictions.

“I think we might find birds flying around the tree.”

“There could be caterpillars on the tree.”

“I already see a bee flying around, so we will see bees.”

“We may find spider webs on the shrub.”

“I think there will be frogs on the tree.”

No,” said another student, “frogs live near water not on trees.” “Well it could be a tree frog,” the first student clarified.

After this preliminary discussion, groups were given a field guide to use for identification and to gather more information about their outdoor learning lab. One group recognized the dogwood tree from previous experiences. “I have seen this tree in my grandmother’s yard.” Even though the crepe myrtle is a very common plant for the area, students were not as familiar with it. Students used field guides to confirm identification, detail key physical characteristics, and describe two common uses of their tree or shrub. For example, “Our tree is the dogwood, it has white flowers and the bark is a little red.” And “Sometimes the tree has red berries on it, which the book says are the seeds. The seeds are eaten by birds.”

Explore

The explore portion of the lesson began with asking students, “What do you want to know about your outdoor learning lab? Students asked the following questions: “What kind of bugs will we find in our outdoor learning lab?” “Will each group find the same bugs?” “Will we find animals other than bugs?”

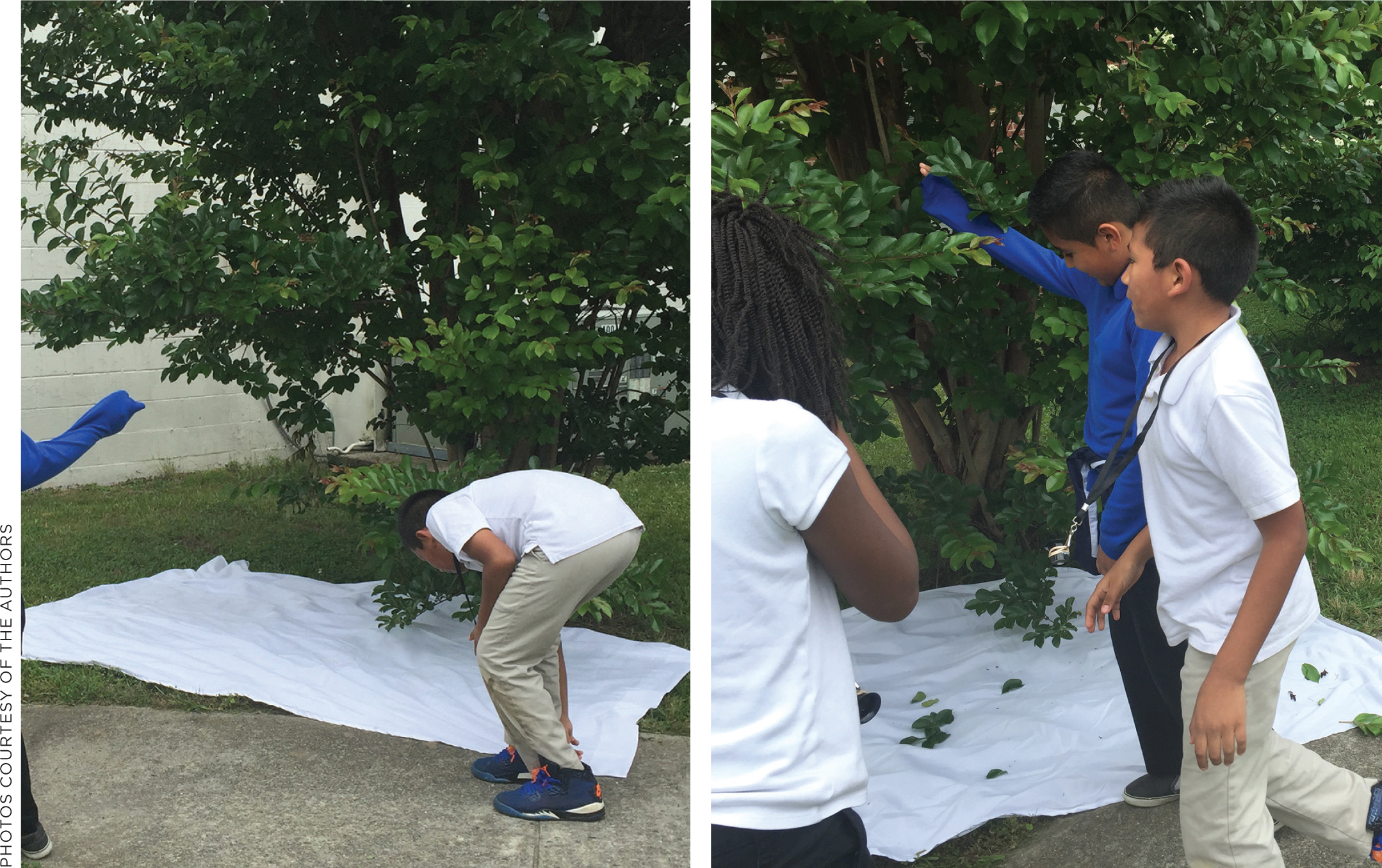

Materials and instructions were given to each group in a tote bag (see Figure 1). Each student selected the following roles for the investigation: one “shaker,” two “capturers,” one “recorder,” and one “spokesperson.” Placing a white sheet underneath the tree or shrub created the boundary for each groups’ outdoor learning lab for collecting data and defining the system of study (e.g., tree or shrub). Once the sheet was in place the “shaker” was instructed to vigorously shake the plant, the two “capturers” were in position to capture whatever dropped on the sheet, and the recorder stood ready to record what was found (see Figure 2 for safety precautions). This process of collecting data (e.g., arthropods) was very engaging and exciting for students. They squealed with joy each time someone found something new. The arthropods were collected into containers for further observation. Once a variety of specimens were collected, students used the arthropod order data sheet (see NSTA Connection) to begin documenting the abundance of diversity found.

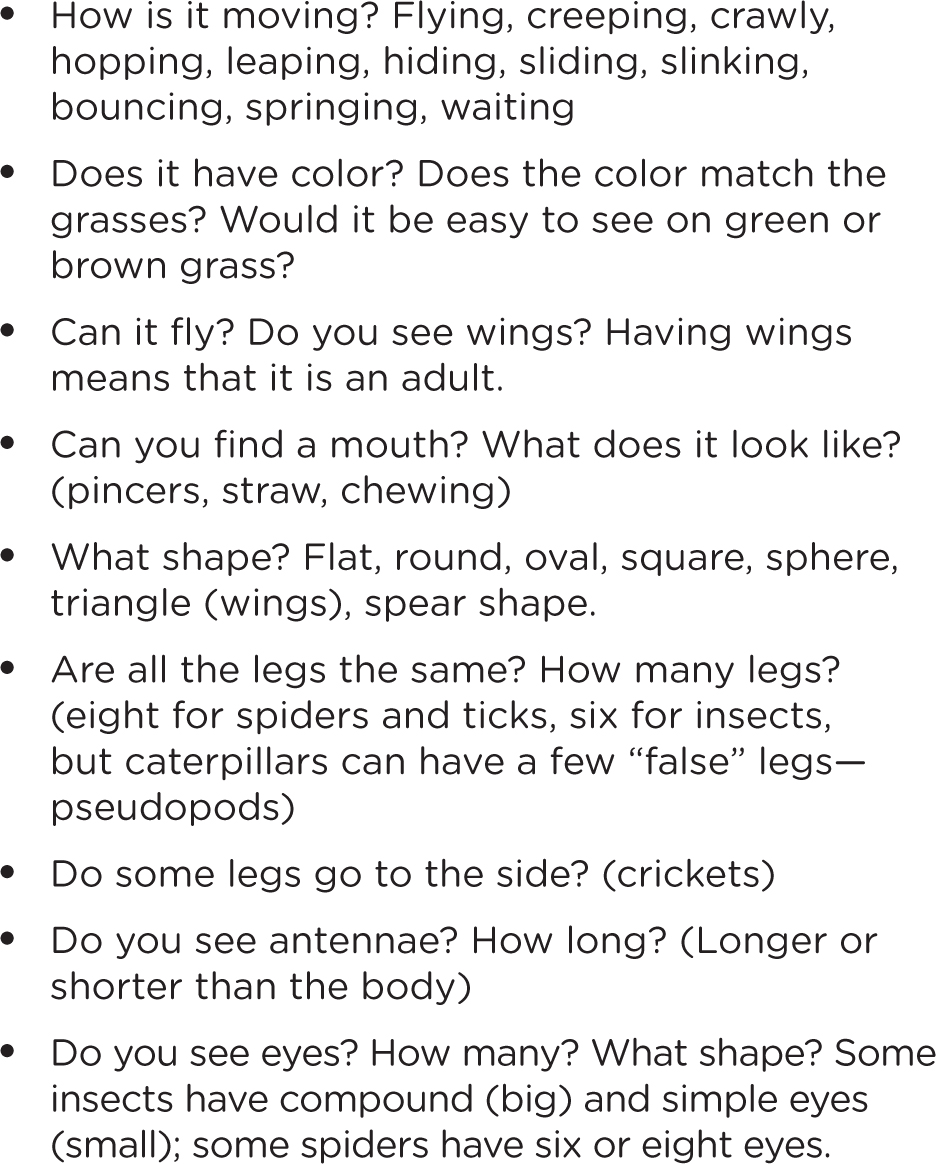

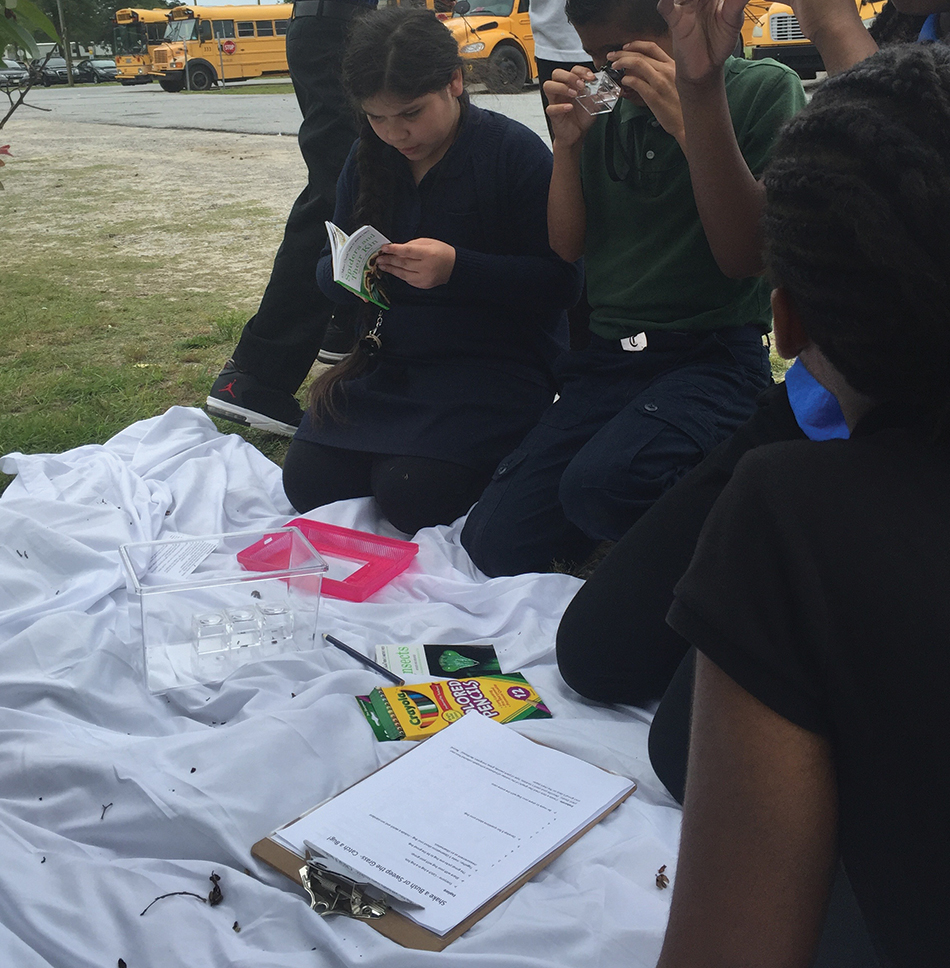

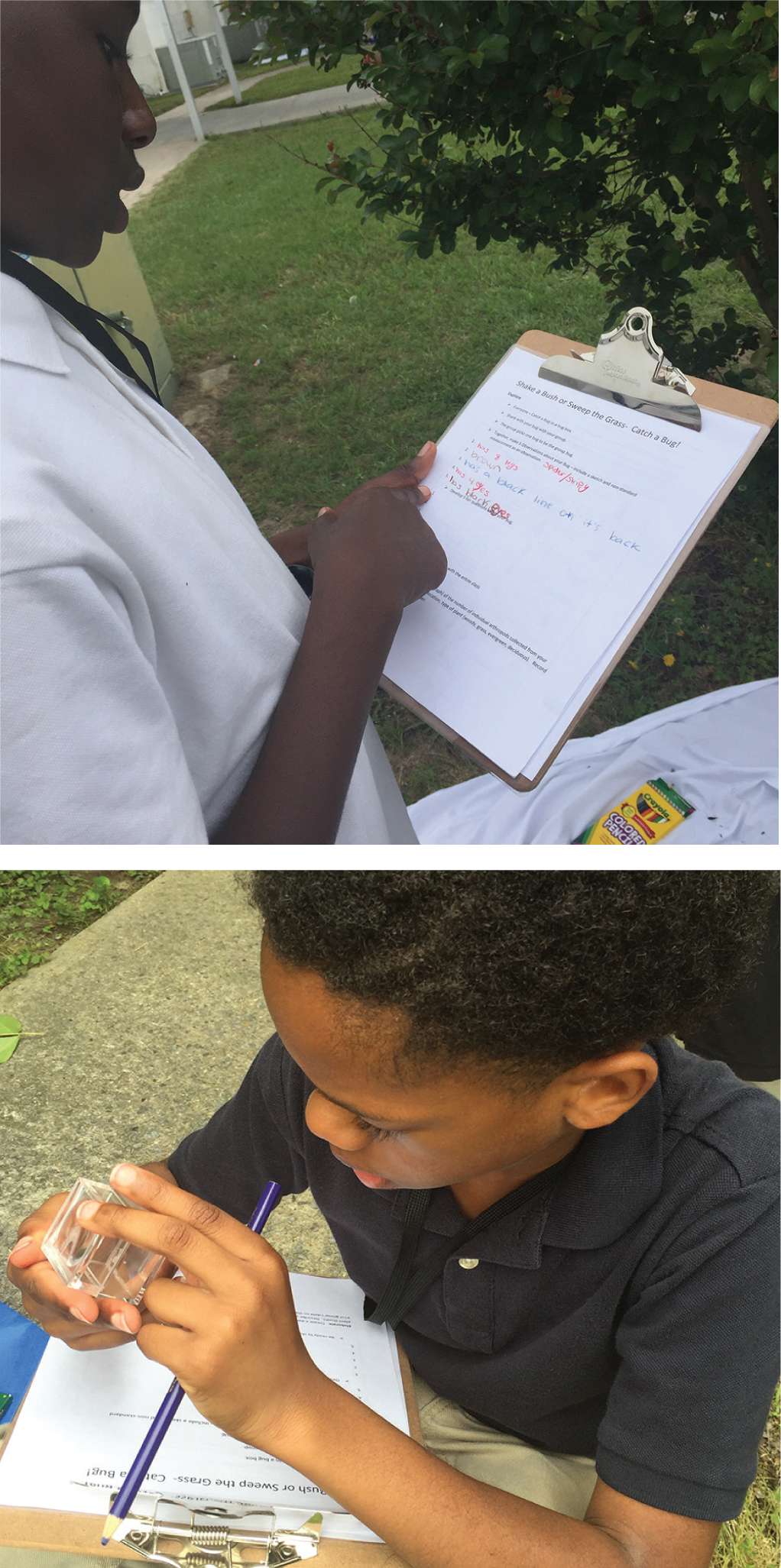

Each group was asked to select one arthropod for a detailed examination. Students were asked to use a list of “fair questions” when making observations of their living organisms (Figure 3). “Fair questions” are ones that can be answered without prior knowledge but based solely from observations. This strategy helps students to ask focused questions based on what they are observing, so that they or any student can answer them through their own exploration. Each group was instructed to make five observations about their bug (arthropod), to invent a name for their bug, to develop their own fair questions, and to use a field guide (e.g., Golden Guide to Insects) to try and identify their selected bug (arthropod). When students are tasked with name creation (prior to identification), they are empowered to feel more like scientists that have discovered a new species.

Students set up and explore their outdoor learning environment

Explain

The explain stage of the lesson began with students sharing their selected arthropod with the rest of the class. One student carried around the specimen (inside a container) for the rest of the class to see while the reporter shared the groups’ observations, invented name, fair questions, and their ideas for identification.

Next, students were guided to sort organisms based on a variety of characteristics that led to a discussion of the components and workings of an ecosystem. The classification analyses and interpretation of data discussion began with asking the following questions: “Can you sort your arthropods by the number of legs they have?” By starting with this question, students were able to distinguish the differences and similarities between insects, spiders, and other groups of arthropods, which led to understanding of concepts of taxonomy and relatedness. This led to us asking, “How do your arthropods move?” students provided answers like, “They crawl!” and “They fly!” Grouping by movement led to a discussion of different parts of the microhabitat or ecosystem, for example, the surface of the plant, the soil, and the air. Students used additional resources like field guides to answer questions like “What do arthropods eat?” in order to illustrate roles in the ecosystem including producers, consumers, and decomposers. After this guided discussion, students recorded this information on their arthropod order data sheet. When all activities were completed, students released all organisms to their appropriate habitat, which models proper care and concern for these living creatures.

Students use field guides to identify specimens.

Elaborate

The purpose of the elaboration stage was to evaluate students’ knowledge of a function (e.g., matter and energy flow) of this ecosystem. This was accomplished by reemphasizing two ideas: (1) the diversity of living things and (2) the interactions and relationships between these living things. Students were asked to refer back to the arthropod order data sheet and to create a table summarizing their findings. Using their data collection sheet as a reference, students counted and classified which orders of arthropods they had collected. For example, the recorder in the group may have tallied each type of arthropod as it was captured. These tallies were counted and each group created a table of orders found. If time had allowed, the tables generated by each group would have been combined into a class graph.

Next, the concept of a system was reinforced. Students were asked, “Is your tree or shrub a system?” Students were asked to describe their outdoor learning lab (tree or shrub) in terms of its parts and how those parts have functions that influence one another, which provides the tree or shrub its overall function of a living thing. For example, teachers and students discussed the functions of the parts of plants (e.g., roots [bring water and nutrients], stem [support the plant], leaves [photosynthesis], and flowers [pollination]. The teachers further explained that the parts of a system worked together through interactions and/or relationships for the overall function of the system to occur. Students had the following responses about their tree or shrub being a system. “The dogwood tree is a system. It has lots of parts like branches and leaves and some of the bugs eat those leaves” and “There are some bugs that eat nectar from the flowers on the crepe myrtle, which pollinates the plant.”

Students record observations (top) and examine collected specimens (bottom).

A spider viewed through a loupe (top) and a student excitedly shares her specimen (bottom).

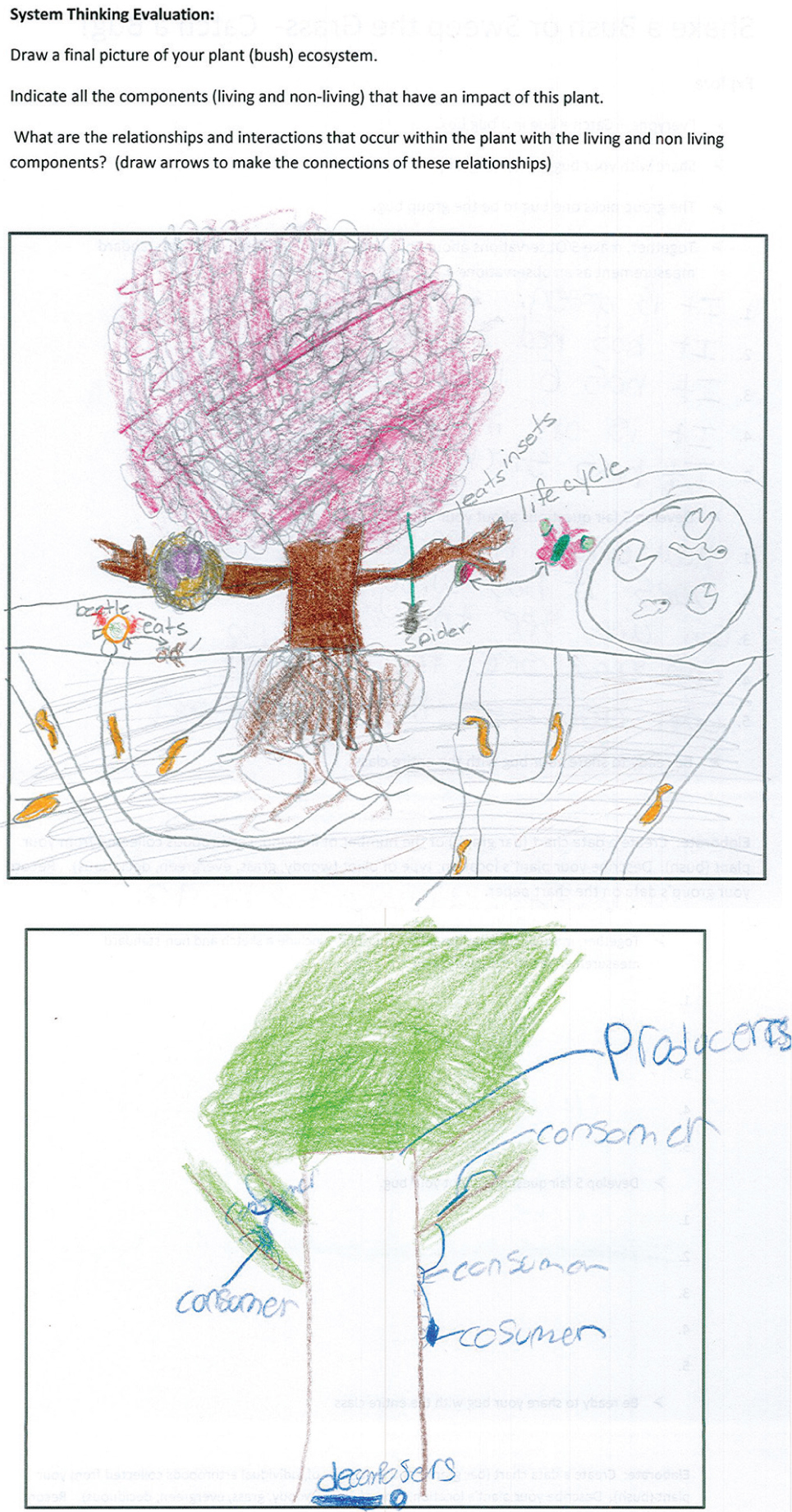

Referring back to our investigations from the explore stage of the lesson, we expanded our discussion of the types of interactions and relationships between living things we had found. For example, students previously noted possible predator-prey relationships between spiders and the order of true bugs they found. After revisiting these interactions, students developed visual models of their outdoor learning labs using their arthropod order data sheet and the tables completed in group discussions (Figure 4). The top drawing shows the relationships of predator and prey, life cycles, a bird’s nest in the tree, and earthworm tunnels occurring underneath the outdoor learning lab. The second drawing illustrates the relationships of producers, consumers, and decomposers. In groups, students used their drawings to share how these relationships illustrate the exchange of energy and matter between living specimens, as in one example where an earwig eats decaying leaves from the crepe myrtle on the ground. The decaying plant matter becomes food for the earwig and also provides nutrients for the shrub (producer) both before and after being eaten by the earwig, in essence representing the cycling of energy and matter.

Evaluate

Throughout this lesson, group discussions and sharing times were used to determine students’ prior knowledge and knowledge obtained through the investigation. Hand-written observations, illustrations, and fair questions completed during the explore stage were used as documentation of their selected arthropod. The arthropod order data sheet was used by each group to create a table of the diversity of arthropods found within their outdoor learning lab. The final evaluation (e.g., System Thinking Evaluation) was a student-created visual model that identified the interactions between components of the system and illustrated the flow of energy and matter.

Conclusion

This lesson focused on using the natural resources available on a school campus as a teaching tool. The student-led exploration of an outdoor learning lab will hopefully inspire students to care about the creatures that live on their school grounds and encourage them to become more curious about the natural spaces around their school and at home.

Tammy D. Lee (leeta@ecu.edu) is an assistant professor of science education at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina. Melissa Dowland is coordinator of teacher education at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, North Carolina. Megan Davis is a teacher education specialist at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Lauren Brewington is a fourth-grade teacher in Greenville. Lauren Pearce is a sixth-grade teacher in Louisburg, North Carolina.

Biology Life Science Elementary