feature

Debating the Future of the American Serengeti

Using Wolves to Engage Students in Argumentation from Evidence

Science courses have traditionally focused heavily on memorization. This focus has been especially true in my high school and college life science classes, which often demanded that I recall countless facts and statistics. Although this strategy still plays a role in science education, I no longer view rote memorization as the most appropriate approach to teaching science in high school. As educators, we are starting to see the value in providing meaningful experiences to help students cultivate the skills needed to succeed in science and their everyday lives.

In my classroom, a prime example of authentic learning has come in the form of a town hall–style debate on managing wolves in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). This lesson forces students to consider the viewpoints of multiple stakeholder groups, using the management of the GYE wolf population as an anchoring phenomenon. This approach emphasized NGSS science and engineering skill Engaging in Argument From Evidence while also incorporating the NGSS disciplinary core idea LS2.C: ecosystem dynamics, functioning, and resilience as well as the crosscutting concept of stability and change (NGSS Lead States 2013).

Students like Rylee Tighe saw the value of this wolf town hall debate (WTHD) in developing their science skills “An opportunity like this is very unique, and it was exciting to take on a role I never thought possible. As the Defenders of Wildlife, we had a lot of groups questioning us. Although it was sometimes difficult to answer those questions, we attempted to handle whatever was thrown at us and really dive into the discussion.”

Eamonn McGovern agreed, “I prepared for the wolf town hall by reading a variety of academic and government literature. Although some of these sources were dense, I feel that obtaining and synthesizing information relevant to wolf conservation significantly strengthened my reading skills and my interdisciplinary understanding of environmental science.”

For Mikayla Mari, the most impactful part of the WTHD was practicing his methods of inquiry, “I learned how to question other groups in a way that challenged their thinking without deprecating their stance. My worldview expanded because I got to hear from every stakeholder and realized that there is always more than one side to a story.”

Lesson description

The WTHD is part of a larger unit on natural resource management intended for high school students in an environmental science classroom. The WTHD is a multiday lesson designed to give students time to build their background knowledge of wolf management before immersing themselves into their stakeholder group. The structure indicated below has been designed for an A/B block schedule over seven class days.

Part 1: Setting context and purpose

A key purpose of this case study was for students to adopt a viewpoint that may not be representative of their own, forcing students to expand their worldview and cultivate empathy for others. As such, students were asked to represent a stakeholder group in the WTHD regarding how best to manage the wolf population of the GYE. The WTHD allowed students to demonstrate their knowledge of wolf management and has become a favorite activity in my classes.

Part 2: Building background knowledge

Students had previously learned concepts from NGSS DCI LS2.C: ecosystem dynamics, functioning, and resilience as a part of class and were forced to draw on this background knowledge and consider how to apply these ideas to the GYE. For example, students had to investigate the various complicated ramifications of the “boom and bust” cycle exhibited by the elk population in Yellowstone National Park. In their preparation for the WTHD, students had to consider how changes in the elk population can be induced by natural and anthropogenic factors such as predation by wolves as well as hunting by people.

Furthermore, they had to consider how these fluctuations in the elk population presented challenges in the GYE, including the stability of the ecosystem as a whole as well as for stakeholders in the surrounding community. This is especially true from the perspective of hunting groups who see reductions in elk populations as a loss of income attributable directly to wolves and put pressure on the National Park Service to curtail the wolf population.

Building additional background knowledge was a key aspect of this lesson. The episode “The Return of the Wolves” from America’s National Parks Podcast (Epperson 2020) introduced students to how wolves were extirpated from Yellowstone. It was a great opportunity for students to explore the ecological value wolves provide as apex predators and the trophic cascades wolves generate.

In listening to an episode from The Wild podcast titled “The Wolf Ranger” (Morgan and Martin 2020) students explored the challenges wolves pose to cattle ranchers and other livestock managers. Wolves are known to prey on cattle, especially when hunters kill alpha wolves, disrupting the pack order. But as Morgan and Martin explain, nonlethal measures, including wolf rangers and wolf-proof fencing, help keep wolves and ranchers safe from one another.

One final resource students had access to was the National Park Service’s annual “Yellowstone Resources and Issues Handbook for Yellowstone National Park” (NPS 2021). This text provided students with a wealth of information on the area’s natural history, including a chapter dedicated to wolves.

Student research and preparation for the WTHD took place during four 75-minute classroom periods over the course of about two calendar weeks. Notably, there were no significant classroom management issues because students truly engaged in what they were doing. In fact, most students described the activity as “exciting, engaging, and fun” and their “favorite lesson of the year.”

One key recommendation for teachers looking to support students during this exercise is that there will not always be a neat, clean answer to every question, which is ok. There is a reason wildlife management is a perennially controversial topic; the goal is to wade into that debate and practice NGSS skills while learning an appreciation for wildlife and land managers.

Part 3: Assign stakeholders

Students were asked to select one of eight different stakeholders including Defenders of Wildlife; the National Park Service; Trophy Mountain Outfitters; Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks; Yellowstone Wolf Guides; the McCall ranching family; the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and Indigenous Voices, which represented the Native American tribes historically tied to the area including the Crow, Blackfeet, and Sioux (National Park Service 2022). Although each tribe has its unique history and worldview, they generally align on wildlife conservation issues (Associated Press 2021), especially wolves (Sutherland and Chakrabarti 2022), hence their inclusion as a single stakeholder group.

Special care was provided for the Indigenous Voices as this group is historically disenfranchised, has suffered numerous injustices, and needed to be represented respectfully. A resource library was provided to help students immerse themselves in their new perspectives and begin preparing, but students were free to discover additional reputable sources to add to the class library.

Students were allowed to choose which stakeholder group they wanted to represent using a digital sign-up sheet. This strategy was designed to maximize student engagement and buy-in to the WTHD. To help scaffold this decision, students were challenged to consider their own personal insights and explore a stakeholder group that helped them tap into their own interests.

Part 4: Research and rehearse

Once students knew their stakeholder group, they began researching their roles, building off their background knowledge of wolf management. Depending on the student level and need, some classes were provided with an organizer document to help them prepare their oral arguments for the actual WTHD. Students used index cards for notes during the actual WTHD and created a class slideshow (Figure 2) where the stakeholder groups provided helpful summaries and graphics for the “general audience” during the town hall.

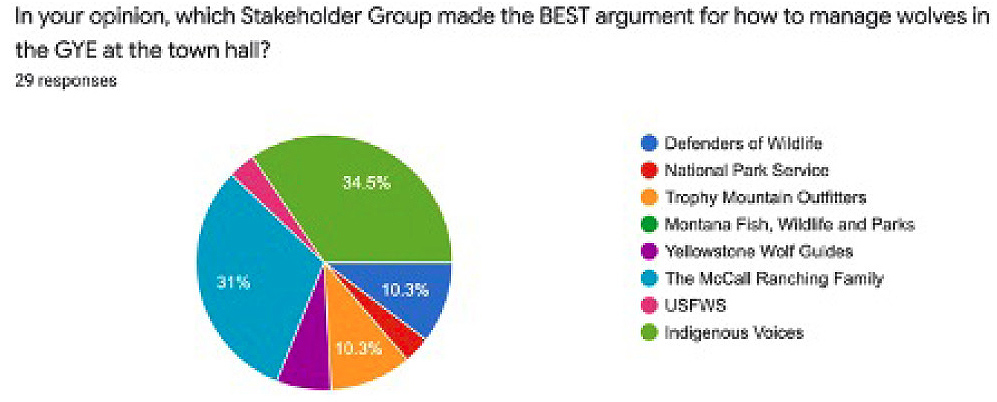

Students voted on which stakeholder group made the most convincing argument for how to best manage the wolf population of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Google Slides document for stakeholder groups to summarize their positions for the audience.

Part 5: Wolf town hall debate

The WTHD was divided into three rounds, which took approximately one hour to complete. In the first round, each stakeholder group was allotted one minute to make opening statements. In the second round, each team was allowed two minutes to address and debate the other stakeholder groups. During each stakeholder group’s two minutes, the selected team was permitted to question other groups and comment on their positions. Special emphasis was placed on being respectful and appropriate while debating.

In the third round, each group was allowed one minute to make final remarks. Teams could comment on the proposals of the other stakeholders but could not actively address them. After all remarks had been made, the “town citizens” voted to determine which stakeholder group made the most convincing argument (Figure 2). The town citizens consisted of myself and a ninth-grade biology class that was allowed to hear the debate to learn more about the topic. A few days prior to the WTHD, the biology students had been provided with a short, written primer outlining the controversy surrounding the management of wolves in Yellowstone. The primer included numerous wolf-related resources, including many of the podcasts students had reviewed to prepare for the WTHD.

Assessment during the WTHD focused on students’ ability to make a convincing argument using specific, objective facts, statistics, and details as evidence. A more detailed discussion of the rubric is located in Part 7.

Part 6: Finding equitable solutions

The final piece of the WTHD challenged students to come back together and develop a workable wolf management plan for the GYE. The students continued advocating for their stakeholder groups but were now challenged to find a solution for how to manage the Yellowstone wolf population. Their plan had to address the needs of all stakeholders while also being realistic in its goals. This activity underscored the challenge wildlife managers routinely face in balancing the needs of multiple stakeholders and forced students to develop empathy and compassion for others.

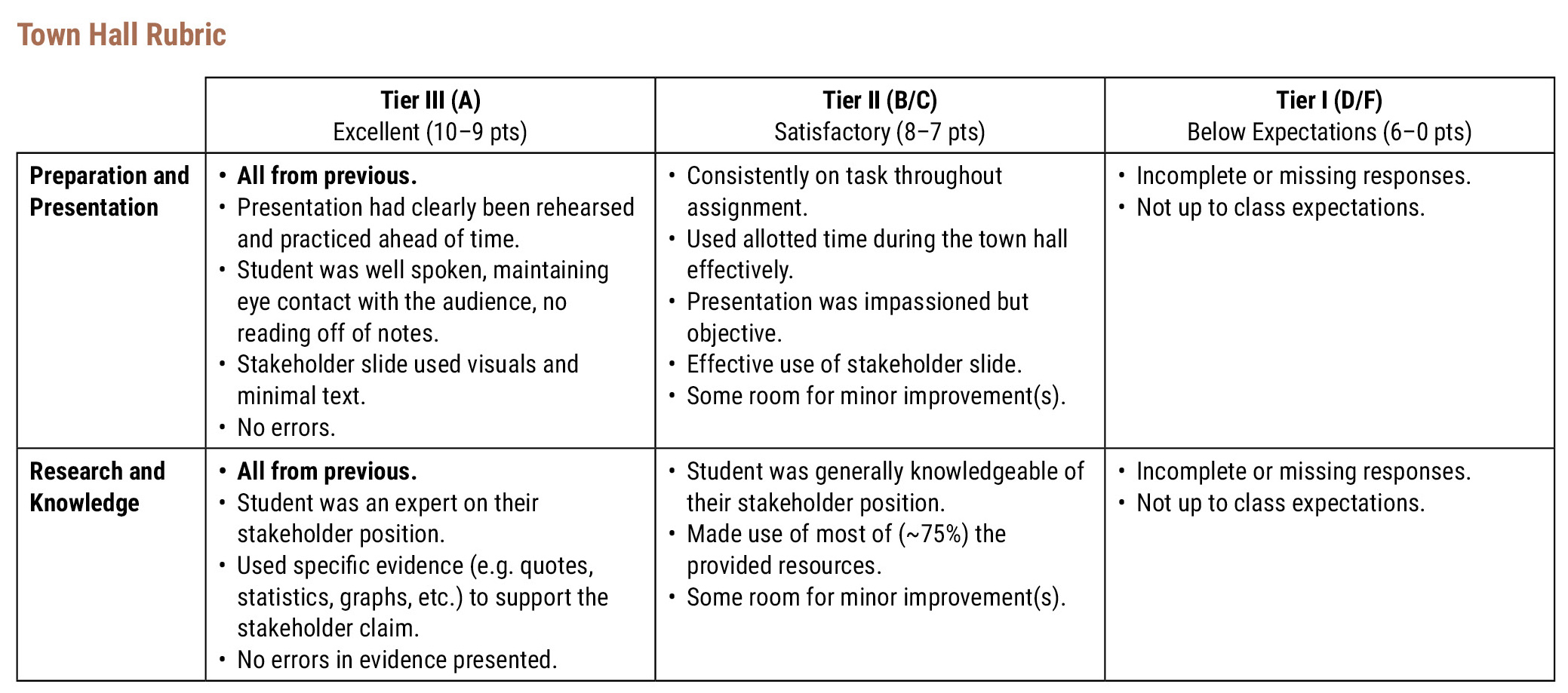

Part 7: Assessing students

A rubric (Figure 3) was used to assess students, especially on the NGSS science and engineering skill engaging in argument from evidence. This rubric evaluated students based on their preparation and presentation during the actual WTHD as well as the research and knowledge they exhibited. Even though the rubric was used primarily as a form of summative evaluation, there were numerous opportunities for formative assessment through the assignment. In particular, the reflections made by students during Part 6 provided opportunities for students to assess their own level of knowledge and ability to work cooperatively with others toward a common goal.

Impact of the town hall: Learning to treasure our environmental resources

In addition to building student science skills, a major goal of the WTHD was to highlight the intrinsic value of our environmental resources, especially wildlife and the ecosystems they need to survive. The real tragedy of nature is that we often take it for granted, forgetting just how fragile and vulnerable our natural spaces can be. Two people working to reverse this erosion of global resources are Chris Morgan and Daniel Curry.

Mr. Morgan is a world-renowned ecologist and host of the radio broadcast The Wild. One episode in particular, “The Wolf Ranger” has become especially important to the wolf management case study. It uncovers the tension between conservationists who want to see wolves returned to the landscape, cattle ranchers who fear for their livestock, and one man looking to help keep the peace.

As the titular wolf ranger, Mr. Curry is a wolf expert and wildlife tracker whose goal is to act as “a bridge between animals and people” as stated on his personal website. Mr. Curry has a tough job trying to meet the needs of those two disparate stakeholder groups who don’t often see eye-to-eye, but his work is vital to the long-term sustainability of wolves, wildlife, and our environmental resources.

This year, we were exceptionally fortunate to have included Chris Morgan and Daniel Curry as guests during the students’ WTHD. Both Mr. Morgan and Mr. Curry loved the event. They were particularly moved by the level of knowledge, passion, and kindness the students demonstrated even in the most heated moments of the event.

Mr. Morgan shared, “Participating in a Q&A, and then the Wolf Town Hall meeting with Mr. Rittner and his students, was incredibly inspiring for so many reasons. It was such a powerful example of the conservation in action we all strive for as people in the field of ecology and wildlife studies. His students’ depth of knowledge on the subject of wolf management was very impressive. Their grasp of the nuances of wildlife management, and the many complex relationships it involves, was far beyond my expectations.”

Mr. Curry commented, “What I saw was students handling themselves with respect towards one another; being sensitive to each other’s viewpoints while respecting their own positions. I was genuinely surprised when I saw some very creative and outside-the-box strategies come to the foreground. That is what I call the ‘Creation of Collaboration’—something the world is currently in great need of.”

Impact of the town hall: Student experiences and reflections

The ability to hold discussions on controversial topics rooted in evidence and respect for others is a fundamental part of science education and a real-world skill everyone needs. Today, our society is more divided than ever on everything from politics and fake news to regulating carbon and oil drilling (Lauter 2021). We need more listening, collaborating, and compromising to build a more fair and just society.

Not surprisingly, the students quickly picked up on this theme as they considered what the WTHD meant to them. The following quotes were taken directly from students regarding their reflections on the activity and highlighted why they felt this lesson was important in becoming more informed global citizens:

“The wolf town hall debate exemplified the idea of how important it is to listen to all stakeholder perspectives to fully address and understand the issue at hand. This debate promoted a deeper understanding of environmental equity and supported our research skills as a class because we were all able to learn more about this complex issue and all of the intricacies surrounding it.”

—Owen Higinbotham

“The wolf town hall debate presented an opportunity for us to immerse ourselves in multicultural perspectives while also developing empathy for others. Seeing my peers’ dedication to the debate, their extensive research, and their ability to listen was beyond impressive. Today’s world is quite polarized, but watching each other craft creative solutions that would benefit all stakeholders gave me hope that there will one day be a solution for wolf management.”—Ava Billotto

“Being able to hear my thoughtful peers’ statements has only expanded my curiosity and knowledge in the world of wolf management and is something that I will continue to explore for the rest of my life.”—Abigail Balagot

“Within the various perspectives presented at the town hall debate, an overarching sentiment was established: that achieving environmental equity takes more than recognizing its absence and requires its proponents to assess and understand the reasons of its detractors, so that we may achieve a consensus whose benefits we all can reap.”—Ayden Mullins

Zachary F. Rittner (zrittner@spfk12.org) is a science teacher at Scotch Plains-Fanwood High School, Scotch Plains, NJ.

Environmental Science Life Science NGSS Science and Engineering Practices Teaching Strategies