How NGSS and CCSS for ELA/Literacy Address Argument

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-07-25

In the summer of 2015, I observed an elementary science teacher from an NGSS-adopted state who made a presentation to her cohort of close to 100 K–12 science teacher leaders and administrators from schools, districts, and the state. After presenting her instruction on a physical science unit with 2nd-grade students, she gave her students the following assignment: “Write your opinion on . . . (the science topic).”

As a science educator, I was struck by the presenter’s use of “opinion” in science instruction. In an effort to unpack my misgivings, I decided to take a quick look at what the new science standards had to say about “opinion” in relation to argument. First, I consulted the Framework (NRC 2012), which states, “[y]oung students can begin by constructing an argument” and “begin to distinguish evidence from opinion” (p. 73). For example, the performance expectation K-ESS2-2 in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) states: Construct an argument supported by evidence for how plants and animals (including humans) can change the environment to meet their needs.

I then turned my attention to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for ELA/literacy. To my surprise, I discovered that “evidence” is introduced for the first time and used only once in grade 3, while “claim” is introduced for the first time and used only once in grade 5. In addition, “reasons” is used throughout K–5 and “reasoning” is introduced for the first time in grade 6. Finally, in grades 6–12, “argument” is used along with evidence, claim, and reasons or reasoning. The CCSS Appendix A (NGA Center and CCSSO 2010), which provides the research base for the CCSS, states, “Although young children are not able to produce fully developed logical arguments . . . In grades K–5, the term ‘opinion’ is used to refer to this developing form of argument” (p. 23).

A key instructional shift in the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS involves making connections across subject areas, which more accurately represent the reality of teachers and students who are trying to make meaning of multiple subject areas that have traditionally been treated in silos. One disciplinary practice that is emphasized consistently across the CCSS for ELA/literacy and mathematics and the NGSS is argument. But to what extent do subject area educators have a common understanding of argument?

In preparing a recent research article for publication (Lee 2017), I attempted to address this question more systematically. As both the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS claim to be research-based, reviewers of the journal encouraged me to look into relevant literature in ELA/literacy and science education with the aim of identifying conceptual sources of convergences and discrepancies between these two sets of standards. Eventually, my analysis of the two bodies of research literature and the two sets of standards in ELA/literacy and science education focused on (1) what counts as argument (i.e., disciplinary norms) and (2) when children are capable of engaging in argument (i.e., developmental progressions). Key findings are summarized as follows:

- Although the CCSS for ELA/literacy include many purposes of arguments, including persuasive arguments, they emphasize logical arguments in relation to college and career readiness.

- The description of argument in science that appears in the CCSS for ELA/literacy is comparable to how the Framework (NRC 2012) and the NGSS describe argument.

- The two sets of standards and relevant bodies of literature in ELA/literacy and science education acknowledge that what counts as argument or evidence differs across disciplines, but none offer explicit guidance on what these differences entail.

- The two sets of standards and relevant bodies of literature in ELA/literacy and science education present differing perspectives on K-5 students’ ability to engage in argument, as described above.

I support the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS in their efforts to make connections across subject areas and to highlight synergy and shared responsibilities among subject area educators. While capitalizing on convergences, it is equally important to reconcile discrepancies between different sets of standards and between different bodies of research literature. As new content standards are being implemented, the education community should attend to discrepancies between and across subject areas and commit to addressing such discrepancies. As a point of departure, a convening of stakeholders to discuss and resolve the discrepancies involving argument is one possible step to take, which could lead to further research and policy initiatives.

With the adoption of the CCSS and the NGSS across states, the responsibility of implementing these new standards falls primarily on classroom teachers. They are faced with limited information about what counts as argument across ELA/literacy and science education. Furthermore, they must contend with discrepant information about when children are able to engage in argument. As the NGSS are aligned closely with the grade-by-grade standards in the CCSS, such discrepancies have practical implications for classroom instruction and assessment. I was relieved and delighted when two leaders involved in writing the CCSS for ELA/literacy deferred to “research in science indicating young children could form arguments” and suggested that “as states are revising standards, they should take into consideration new research that’s out there” (Zubrzycki, 2017). In a similar manner, teachers and school districts should expect K-5 students to engage in argument from evidence consistently across subject areas, including ELA/literacy.

References

Lee, O. 2017. Common Core State Standards for ELA/literacy and Next Generation Science Standards: Convergences and discrepancies using argument as an example. Educational Researcher, 46(2), 90-102.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). 2010. Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Appendix A: Research supporting key elements of the standards, glossary of key terms. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_A.pdf

National Research Council (NRC). 2012. A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Zubrzycki, J. 2017. In elementary school science, what’s at stake when we call an ‘argument’ an ‘opinion’? Education Week, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2017/04/science_standards_common_core.html

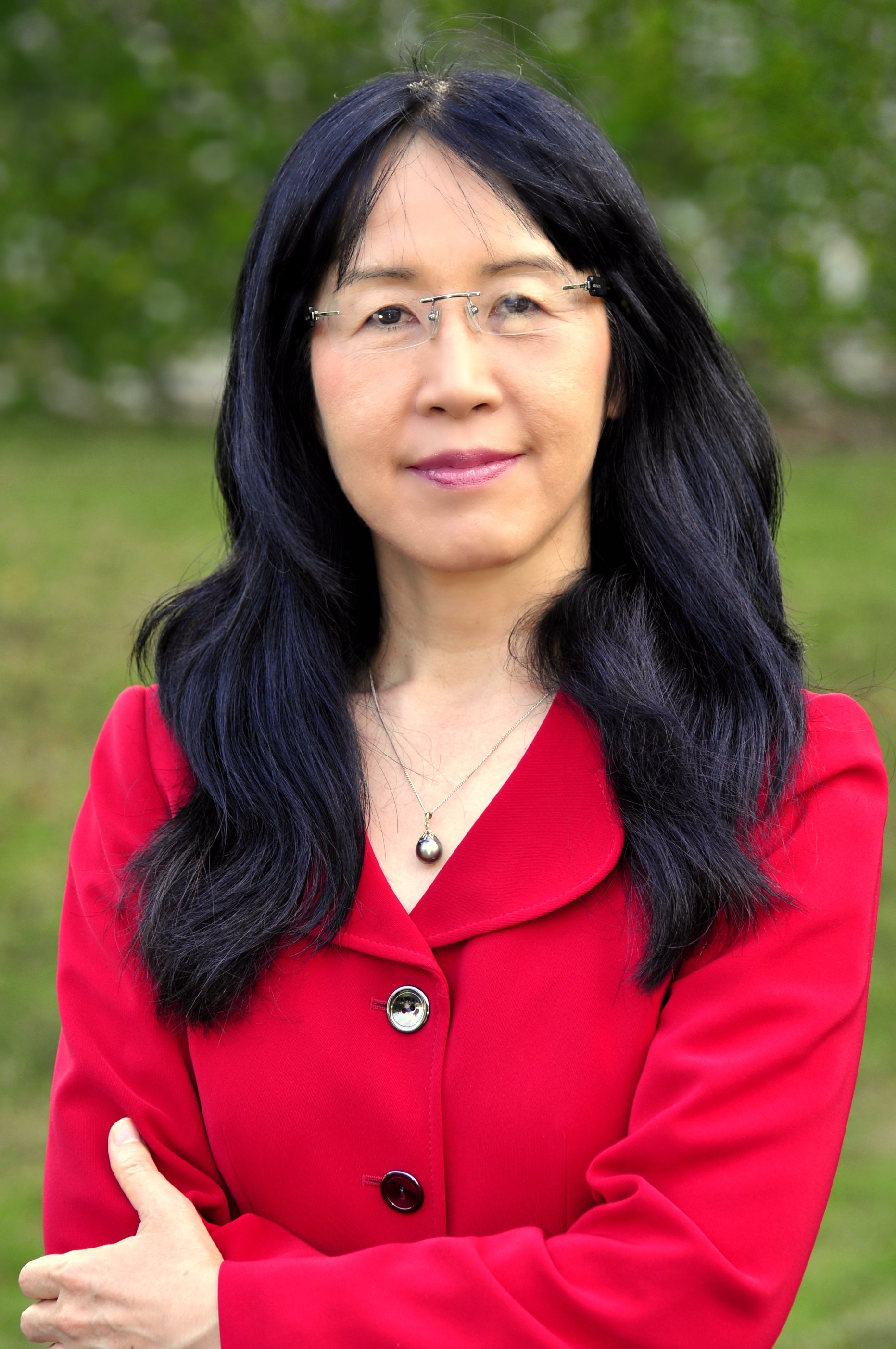

Okhee Lee

Okhee Lee is a professor in the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University. She was a member of the NGSS writing team and served as leader for the NGSS Diversity and Equity Team. She is currently developing NGSS-aligned instructional materials for students, especially English learners, in fifth grade.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

Crosscutting Concepts Disciplinary Core Ideas Literacy NGSS Policy Middle School Elementary High School