Feature

Connecting Fossil Clubs With K–12 Teachers

Connected Science Learning April-June 2018 (Volume 1, Issue 6)

By Jeanette Pirlo, Bruce J. MacFadden, Eleanor E. Gardner, Victor J. Perez, and Denise Porcello

FOSSILs4Teachers! is a professional development workshop that allows K–12 educators and museum paleontologists to collaborate on fossil resources and standards-aligned lesson plans about fossils.

Since 2013 the National Science Foundation (NSF)–funded FOSSIL project has developed a national network of paleontology clubs, whose membership includes amateur and professional paleontologists, and natural history museums (MacFadden et al. 2016). More than 5,000 fossil club members and other enthusiasts have connected to the FOSSIL learning community via its website, www.myfossil.org, and social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

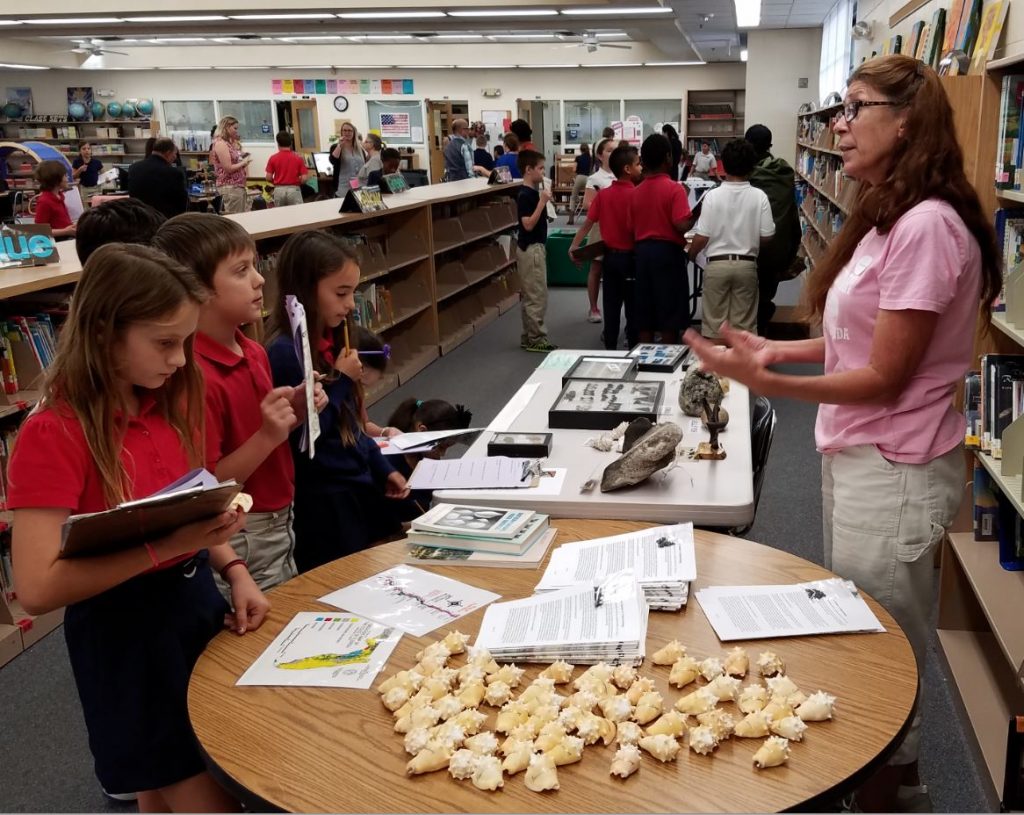

FOSSIL has also attracted the interest of other individuals, including K–12 teachers and students. Fossil club members are consummate collectors, and many have developed considerable private collections that can potentially be used for K–12 education. Although many fossil clubs have K–12 education and outreach programs, these are not widespread and certainly not networked above a regional level. Further, many club members lack training in how best to connect with teachers (e.g., awareness of K–12 formal education standards, such as the Next Generation Science Standards [NGSS Lead States 2013]). Conversely, many teachers do not have access to fossil clubs, mainly because no fossil club exists in their area. In these cases, it is often difficult for these teachers to know where to acquire actual fossils for classroom instruction, or lack content knowledge about paleontology. With all of these factors in mind, we saw an opportunity to bring together two audiences and connect the informal (fossil club) and formal (K–12) communities for mutual benefit.

In August 2017 we implemented a four-day professional development (PD) workshop called FOSSILs4Teachers! at the Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH) at the University of Florida. During this workshop, almost three dozen fossil club members, K–12 teachers, and professional paleontologists came together to exchange paleontology knowledge, share fossils, and develop lesson plans for the classroom. Paleontology might at first glance seem like a rather narrow domain within the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, but this interdisciplinary field is actually a charismatic gateway to teaching students content related to biology, geology, physics, engineering, math, and technology. Thus, if properly structured, paleontology can be presented in lessons at all K–12 grade levels. The goals of FOSSILs4Teachers! were to:

1. increase collaboration between paleontologists and K–12 teachers,

2. provide teachers with actual fossils that can be used in the classroom,

3. develop paleontology-focused lesson plans to teach concepts relevant to formal K–12 education standards and important topics of societal interest (e.g., evolution, climate change), and

4. increase participants’ general knowledge of fossils and paleontology.

The results and implications of our pilot workshop indicate the benefits of and emerging potential for connecting fossil clubs and K–12 teachers on a national level. Teachers have expressed a need for content knowledge and to have real fossils in the classroom, whereas fossil club members have expressed a desire to share their experiences and specimens for education and outreach. FOSSILs4Teachers! served as the spark that made these groups aware of their shared interests, and more importantly, the myFOSSIL website provided a platform for sustained networking that can be used by anyone in the world.

Photo by Jeff Gage, FLMNH

Connecting informal and formal audiences

In developing the program, we identified two major participant audiences:

- amateur paleontologists (informal education), most of whom are members of fossil clubs, and

- K–12 STEM teachers (formal education).

Ten of our participants spanned both groups, i.e., teachers who are also members of an existing fossil club or society (collectively referred to for the remainder of this article as “club”). The importance of facilitating connections between formal and informal education entities, such as after-school or library programs, has been well established (e.g., Mokros et al. 2017), but little has been documented about the value of connecting formal educators with avocational groups such as fossil collectors. Our prior research indicates that about 60 organized clubs and amateur societies exist in the United States (MacFadden et al. 2016), about three dozen of which are part of the FOSSIL Network. We focused on fossil club members because they are knowledgeable about paleontology, passionate about their avocation, and many enjoy collaborating with teachers in the classroom. Additionally, many fossil clubs are nonprofit organizations with missions to educate the public about the geological and paleontological history of their respective regions. Thus, connecting STEM teachers with fossil club members is a win for everyone in science education.

Pam Plummer, PD participant

Our recruitment and selection methods involved the following process:

- We advertised the PD opportunity through our FOSSIL Project Facebook and Twitter social media platforms and the myFOSSIL community website.

- We sent e-mails to fossil clubs to reach members who do not engage in social media.

Selection for the PD opportunity for both club members and teachers was based on:

- individuals’ responses to a series of application questions,

- level of participation in the myFOSSIL online community,

- an attempt to diversify and broaden the representation of the participants; and

- geographic location.

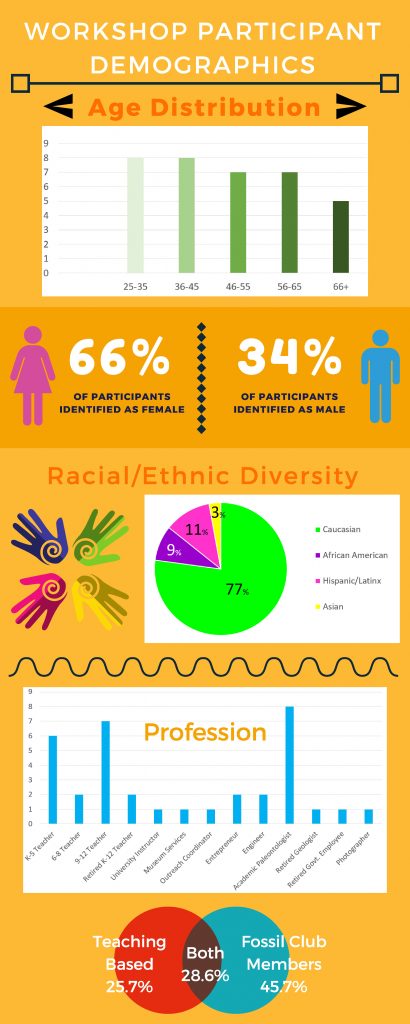

We selected participants who expressed the most passion for outreach activities and ideas for how they would incorporate those activities into the classroom. We selected 28 participants from these two audiences (Figure 1), and seven members of our museum staff also participated as science content experts in the workshop. Participants were from California (1), Florida (19), Georgia (1), Illinois (1), Louisiana (1), Maryland (1), Massachusetts (1), Minnesota (1), Nevada (1), New York (1), North Carolina (1), Tennessee (1), Texas (3), Washington (1), and India (1). We balanced our participant pool by choosing applicants such that two-thirds of the final group had prior experience with the FOSSIL Project; one-third were new participants. The experienced participants mentored the novices during the program.

Geographic location was another factor in the selection process because we wanted to assemble the participants into working groups by general region during the workshop. A main goal of the workshop was to ensure that teachers could receive follow-up paleontology content support from local club members after the workshop ended. This strategy helped us fulfill our first goal of increasing collaboration between formal and informal education audiences.

Another goal of the PD workshop was to highlight the value that greater diversity and inclusivity bring to STEM fields. Our workshop participants were a fairly diverse group in terms of geography and profession; however, we fell short of our goal for racial, ethnic, and gender diversity (Figure 1). Over 75% of participants were Caucasian. This was not unexpected, despite our best efforts to be more inclusive. It has been documented that “adult, community-led science clubs” are overwhelmingly Caucasian (Dawson 2017), and the amateur paleontological community is no exception. However, anecdotal observations via the FOSSIL Project’s social media presence suggest that more minorities are starting to engage with amateur paleontology groups (both online and in-person). We are therefore cautiously optimistic that amateur paleontology groups will become more broadly representative over time. To increase diversity in future programs, we look forward to working with groups that have a direct impact in underserved communities. By indentifying these groups and approaching them with upcoming opportunities, we hope to continue supporting underrepresented groups.

Figure 1

Demographics of the workshop participants, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and profession

Photo by Jeff Gage, FLMNH

The workshop

Prior to the implementation of the PD workshop, we identified and inventoried over 10,000 fossil specimens that had been donated to FLMNH or were part of our unaccessioned collections. Many of these specimens were of museum quality, but lacked the necessary data (e.g., locality, geological context) to incorporate into the museum’s collection. The specimens mostly represented 10 million– to 10,000-year-old (Miocene to Pleistocene) fossils from Florida. To supplement our specimens, participating club members also donated fossils from their own collections, which included various time periods and localities. Some of those specimens were up to 420 million years old and came from other areas of the United States (e.g., New York). All of these fossils were used to develop the fossil kits that each teacher would take back to the classroom.

Denise Porcello, PD participant

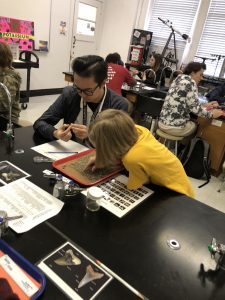

To make this PD experience beneficial to all participants, it was important that the activities and content not only aided in lesson development for K–12 teachers, but also contributed to the learning and engagement of the amateur paleontologists. We therefore balanced the program with daily talks that would appeal to both audiences, along with interactive and hands-on activities.

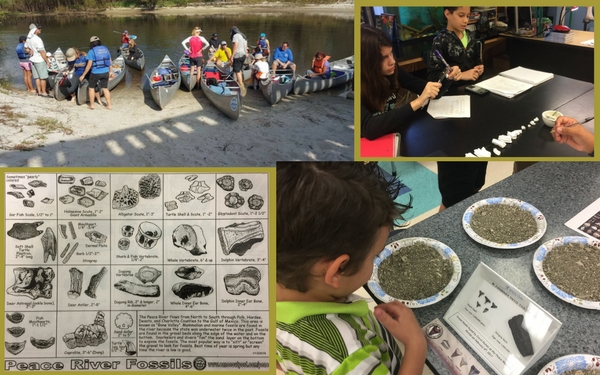

Keynote talks included “Bringing Fossils Into the Classroom,” “Using myFOSSIL as a Learning Tool,” and “NGSS 101” (PD agenda). Interactive activities consisted of behind-the-scenes collections tours, sorting of fossil-rich sediment, a tour of the public exhibits at FLMNH, and a field trip to collect fossils from a creek in Gainesville, Florida. These talks and interactive activities, which increased our participants’ general knowledge of paleontology and its relation to formal K–12 education, facilitated lesson development. We were concerned that the lesson plan development would interest only teachers, but as the participants began to work on their lessons, we saw sustained engagement of all participants throughout the PD workshop. Club members provided the content knowledge, whereas teachers created dynamic lessons.

Photo by Jeff Gage, FLMNH

Time was dedicated each day for teachers to select (and learn about) the fossils they would use to create fossil kits for their classrooms. An important part of using a fossil kit in classroom settings is proper specimen identification and teacher self-efficacy. Teaching science successfully has been attributed to increased confidence in the subject matter (Murphy, Neil, and Beggs 2007), and by providing teachers with tools to help with identification, we can increase their confidence in the subject and their abilitiy to be successful in teaching their students about paleontology. All participants were taught how the myFOSSIL website aids fossil identification. Participants were also provided with two identification guides: (1) the Aurora Fossil Museum’s Fossil Identification Sheet (Aurora Fossil Museum 2017) and (2) “Fossil Sharks and Rays of Gainesville Creeks, Alachua County, Florida” (Boyd 2016). Fossil club members and museum staff provided additional support for identification, as well as general knowledge about the specimens available.

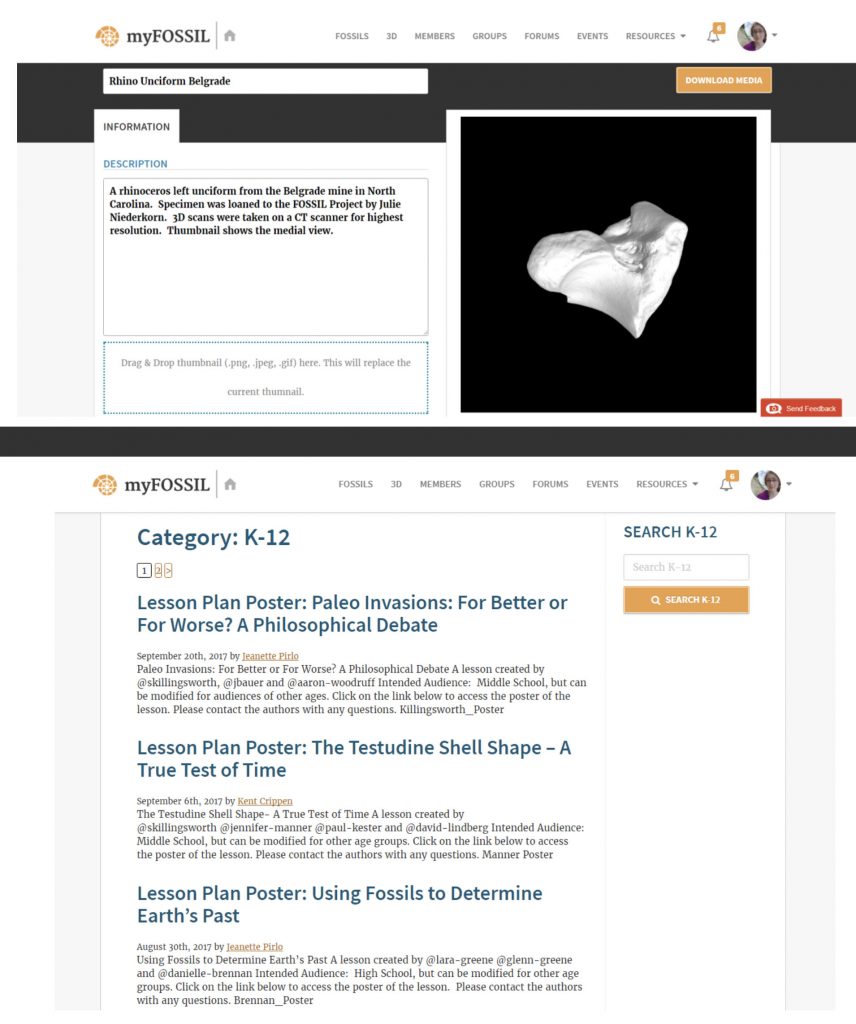

Photo by Jeff Gage, FLMNH

The myFOSSIL community website was presented as a resource (beyond fossil identification) for both formal and informal education audiences. The site allows users to engage in social paleontology, an open and collaborative exchange of ideas related to the collection, preparation, curation, and study of fossils (Crippen et al. 2016). Users connect with professional and amateur paleontologists from around the world via discussion forums, group and club pages, and webinars. STEM resources on myFOSSIL (bottom image in Figure 2) include:

- vetted, standards-aligned curricula,

- paleontology education–focused newsletter articles,

- contacts for field opportunities and fossil club meetings across the United States, and

- videos and tutorials on a variety of paleontology topics.

In the “Fossils” gallery on the website, concepts such as biological classification, geographic origin, geologic time, and geological context can be scaffolded as users upload photos of their fossil collections. The 3-D gallery, which enables users to upload, view, manipulate, and download 3-D images of fossils, can be easily used in technology classrooms (top image in Figure 2).

Figure 2

Two pages from the myFOSSIL website The 3-D fossil gallery (top) and examples of lesson plans available for download (bottom).

Picking fossil matrix—the process of sorting loose sediment containing fossils—was a popular PD activity. It allowed participants to experience a learner-focused, hands-on activity that they could bring back to their classrooms or clubs. FLMNH staff provided 5 to 2 million-year-old (Miocene- to Pliocene-age) matrix from the Lee Creek Mine in Aurora, North Carolina. Fossil collectors covet this material because of its high abundance of shark teeth and other fossils. The mine itself is no longer accessible to collectors; however, matrix that is leftover from the mining process, also known as the spoil pile, is available for education and outreach. Additionally, one participant brought a five-gallon bucket of 35 million-year-old (Eocene) matrix from Alabama. Participants were each given plates, plastic forceps, and their choice of either North Carolina or Alabama matrix (although most ended up sorting both). They were then instructed to pick out fossils from the matrix and use the provided guides to identify what they had found. Participants and staff familiar with the fossils from these sites oversaw the activity and aided the others with identification of their fossils.

At the end of the matrix sorting activity, a group discussion ensued. Participants were asked to interpret the ancient environment at the two fossil sites, noting similarities and differences between the two locations. The inclusion of the Alabama matrix was impromptu; however, it helped highlight that, depending on where fossil matrix comes from, the focus of a lesson using the matrix sorting activity may vary. The activity serves as the foundation for the lesson, but the topics covered can be modified to fit the needs of each instructor.

Every participant was given the opportunity to keep the fossils they picked. They also have the option to request more fossil matrix from North Carolina, through the FOSSIL Project’s website, in the future if they plan to implement the exercise in their formal classroom or informal outreach program. Teachers were also encouraged to contact local fossil clubs to implement the activity using locally sourced material to facilitate a place-based learning experience.

Creating lessons for the classroom

Photo by Jeanette Pirlo, FLMNH

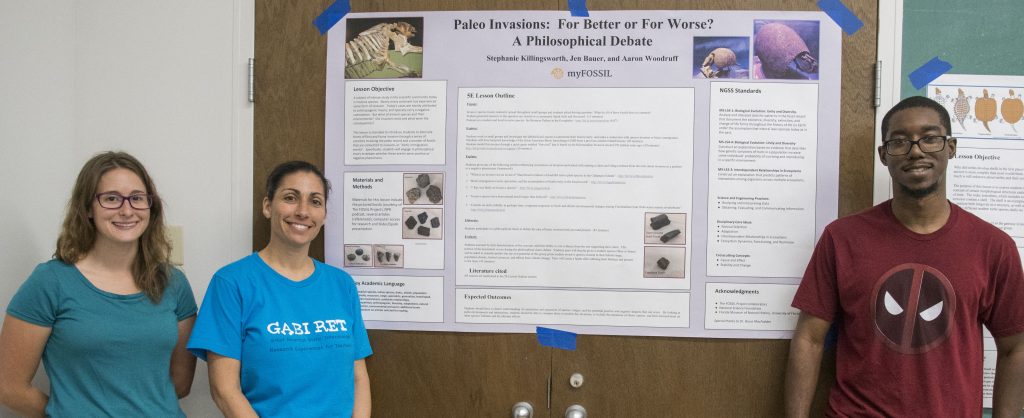

Armed with specimens, paleontological content, and learning mentors, participants were ready to begin lesson planning. We were pleasantly surprised when the participants self-organized into groups based primarily on grade level and region. Each group was asked to create a STEM-integrated lesson using fossils as evidence. They were expected to follow their specific state standards (Table 1) and, if applicable, incorporate the NGSS and the 5E model. The 5E instructional model is used in many K–12 lesson plans because it provides a framework for lesson planning. The Es stand for Engage, Explore, Explain, Extend/Elaborate, and Evaluate (Bybee et al. 2006). Each group presented its lesson as a poster during a conference-style symposium at the end of the PD workshop. Our participants produced 14 lessons, which are all available on the myFOSSIL resource page.

| Lesson title | Intended grade level | Dimension 1: Science and Engineering Practices |

Dimension 2: Disciplinary Core Ideas | Dimension 3: Crosscutting Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inference With Fossils: A Third-Grade Project-Based Lesson Students reflect on the habitat, body size, body weight, and adaptations of fossil organisms through quantitative and qualitative observations. |

3 | Asking Questions and Defining Problems; Planning and Carrying Out Investigations; Developing and Using Models; Analyzing and Interpreting Data; Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions; Engaging in Argument From Evidence | Developing Possible Solutions 3-5-ETS1-1 3-5-EST1-2 Growth and Development of Organisms 3-LS1-1 Inheritance of Traits Variation of Traits 3-LS3-1 3-LS3-2 Adaptation 3-LS4-3 Types of Interactions 3-PS2-1 |

Influence of Science, Engineering, and Technology on Society and the Natural World; Patterns; Cause and Effect; Scale, Proportion, and Quantity; Systems and System Models |

| The Testudine Shell Shape: A True Test of Time Students reflect on the concept that certain morphological structures endure the test of time. |

6–8 | Analyzing and Interpreting Data; Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking; Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions; Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information |

Evidence of Common Ancestry and Diversity MS-LS4-1 |

Patterns |

| Evaluation and Communication of Fossil Evidence Students communicate in the form of an exit slip evidence on how fossils are used to determine evolutionary relationships between different species. |

9 and 10 | Analyzing and Interpreting Data; Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking; Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions; Engaging in Argument From Evidence; Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information. |

Adaptation HS-LS4-1 |

Patterns; Cause and Effect |

At the end of the PD workshop, an optional field trip brought 20 participants to Rattlesnake Creek in Gainesville, Florida. This site contains predominantly 20 to 10 million-year-old (Miocene) marine fossils. The field trip had three main purposes:

- to help participants understand best practices associated with collecting fossils,

- to further encourage collaboration and networking among participants, and

- to give participants another opportunity to bring fossils home.

These purposes align with the first, second, and fourth goals of the PD experience, as outlined above. Additionally, participants were encouraged to use the Boyd (2016) guide to identify their fossils, take pictures of their finds and upload these to the myFOSSIL website, and continue dialogue about fossil identification and student engagement after the PD workshop. As of this publication, over 60 fossils have been uploaded to the website by PD participants.

Cindy Birkner, PD participant

Were we successful?

We surveyed participants to evaluate the efficacy of FOSSILs4Teachers! in achieving the program goals. We hoped to increase the collaboration between amateur paleontologists and K–12 teachers not only during the PD workshop, but after the program as well. Collaborations between our participating amateur paleontologists and K–12 teachers prior to the program were quantified via retrospective questions within the summative evaluation. A consistent response from many teachers was that, prior to the workshop, they did not know any amateur or professional paleontologists. Ten percent of our participants knew a paleontologist prior to this experience; however, they did not feel comfortable collaborating with him or her, because they did not feel that they could keep up with a paleontology-related conversation. Since the PD experience, 80% of our participants agreed that there has been increased communication between the two groups. This can be seen on the FOSSILs4Teachers group page on myFOSSIL and is well-illustrated in this participant’s response:

"Through myFOSSIL, I have an easy way to contact professional and amateur paleontologist[s] to ask questions that I might have about fossils we find or students bring in … [I can also find] teachers that I would feel comfortable sending an e-mail or message. I feel that this workshop has opened up a whole new world for me through the use of myFOSSIL. I have everything I need at my fingertips. I can even have my students use the website to help encourage their exploration of the world of paleontology. I have contacts with people who can help me attain more fossils for my classroom as I am using the lesson plans we all developed. I am so very excited.”

We were also invested in providing thousands of real fossils for teachers to take back to their classrooms. We have seen an increase in communication between teachers and amateur paleontologists discussing the types of fossils they would like to exchange online. A forum thread on myFOSSIL allows members to request fossils from other members. The club members have demonstrated an eagerness to provide more material by stating that they are “providing additional fossils and educational materials as needed for interested teachers and [are] willing to lead field trips for any teachers or amateurs who are interested.”

One critical aspect of the PD workshop was that the participants developed lessons using fossils as evidence of evolution or climate change, which are topics of current societal relevance. The poster lessons are available on the myFOSSIL resource page, and several will be presented at upcoming conferences and monthly club meetings. We also received encouraging feedback regarding fossil use in the classroom, as one of our participants noted:

"I will definitely make my Earth and space class much more fossil-heavy, at least four weeks this year, and my biology class will be much longer as well. Being able to bring back the fossils and lesson plans and having someone that can answer questions my student[s] might have that I don’t know the answers to, through myFOSSIL, will make me so much more confident [in using fossils] in my classroom.”

Denise Porcello, PD participant

Finally, we wanted to ensure that our participants left the PD workshop with greater general STEM content knowledge of fossils and paleontology. This was challenging, given that the participants had different backgrounds and levels of content understanding, whereas many of the amateur paleontologists are experts on their local geology and paleontology. However, by encouraging interactions between all participants, we ensured that each would be exposed to novel content and perspectives. As such, all of our participants indicated that they left with an increased understanding of paleontology. Eighty-five percent felt that their knowledge of paleontology was much higher, whereas 15% felt their knowledge of paleontology was somewhat higher. As one of the participants put it,

"This PD [workshop] was extremely fruitful for me as a K–12 Earth science teacher from India. I am starting a completely new chapter in my school on fossils and paleontology. I learned a lot from my fellow participants in sharing lesson plans and learning so much about fossils and [others’] experience with them. I am connected with our fellow participants through Facebook and myFOSSIL and know that if I have any questions, they can help answer them!”

What did we learn?

This PD workshop was geared toward providing learning experiences for formal and informal science audiences. The overall response to our program was a high degree of satisfaction. In the postsurvey, we received an average overall “A” grade for the PD experience, indicating that the activities provided in this workshop fulfilled the expectations of our participants. Although it may not be feasible for others to replicate this exact experience, we expect that the myFOSSIL website provides the necessary resources for anyone to adapt the activities in this workshop for their specific needs. Some potential limitations for replicating this PD workshop are: time, proximity to fossil clubs and collecting sites, and funding.

During the design of the PD workshop, we kept in mind that teachers would require sufficient time to create lessons; however, we also had to allocate time for providing background knowledge to support these lessons. We crafted the agenda in a way that would allow for brainstorming sessions throughout the day and, once the fossil kit selection was complete, we allowed for more free time for lesson development. Based on the survey responses, we realized that in the future, we need to provide even more time for lesson planning. One possibility could be expanding the experience into a weeklong workshop (or “summer institute”) that would provide more time for lesson planning, without reducing the time spent on providing background knowledge.

Participants responded positively to the interactive activities. The field trip to collect fossils in Rattlesnake Creek was especially popular. For future PD experiences, we will hold the field trip earlier in the program. This will allow participants to incorporate fossils that they find into their lessons, creating a stronger sense of relevance. There was also a request to provide a second field experience, one that exemplified the process of discovery, processing, and cataloguing into a museum’s collection. FLMNH has an active dig site where a field trip of this nature would be possible, particularly if the program is expanded into a weeklong institute. By including two field trips, each demonstrating a different method of collecting, we would provide an opportunity for our future participants to better understand authentic science. This could, however, be a limitation for other institutions that do not have access to nearby collecting sites. The solution to this limitation is matrix sorting, which brings the field experience to the classroom and allows teachers and students to interact with real fossils. The myFOSSIL website provides a platform for anyone to acquire these resources. Thus, regardless of proximity to collecting sites or fossil clubs, teachers still have the capacity to integrate authentic scientific practice in their classrooms. Based on the survey responses and anecdotes, these field experiences and access to real fossils are critical for increasing student engagement.

Florida middle school teacher Stephanie Killingsworth shares her class experience since her participation in the PD workshop:

"Incorporation of fossils in[to] my classroom has revolutionized the students’ understanding of topics like evolution. They have developed stronger critical thinking skills when it comes to understanding how dynamic changes in Earth’s topography and climate can cause adaptive responses in flora and fauna. Letting students hold a 10 million-year-old fossil in their hands can be magical and can transport them back in time. I’ve been so inspired by my own experiences in the field that I have worked to create similar experiences for my students, and their engagement is so rewarding. I am constantly inspired to find new ways of fitting fossils into the curriculum as a result.”

Photo by Jeff Gage, FLMNH

Thanks to the success of this PD workshop, we hope to inspire other museums to provide similar activities to encourage interaction between formal and informal educators. Funding provided by NSF allowed us to bring together 35 participants from all over the country. With NSF support, we were able to cover all costs of travel (e.g., flight, hotel, luggage) and meals. Understanding that other institutions might not have access to the same funding, it is possible to lower expenses by reducing travel costs. For example, costs can be reduced by providing a PD experience for only local educators or a session at a conference where formal and informal educators are present, such as the annual Geological Society of America conference.

Stephanie Killingsworth, PD participant

Conclusion

We anticipate providing further PD workshops similar to the one described in this article. Further, it is apparent that myFOSSIL is an invaluable tool for both teachers and amateur paleontologists, in large part because it provides a platform for discussing ideas. The sustained use of the website by our participants shows that they found value in the tools we provided. We enjoy receiving feedback from teachers about implementation with students, such as this one:

"Today, we were able to explore different fossil teeth and fish barbs, and the students loved it! Just wanted to say thanks for this professional development, because it really showed me how curious the students are! My high school students were completely engaged and loved having actual fossils in their hands!”

We are also impressed with fossil club members’ remarks regarding the use of PD activities in their outreach: “I have witnessed a dramatic transformation like no other in the attendees’ participation and their level of inquiry following my presentations!” We plan to continue working with the workshop participants in various ways, including in-person and video engagement in the classroom and during club meetings and field excursions, and facilitating attendance at professional conferences.

Acknowledgments

Many individuals contributed to the success of FOSSILs4Teachers! We thank all of the participants for their engagement. We are also grateful for all of the fossil contributions, including the matrix, made by participants and outside sources. We thank J. Gage, museum photographer, for photographs taken during the week; B. Dunckel, for the tour at the FLMNH’s new Discovery Zone; R. Portell for his behind-the-scenes tour; S. Moran for his tour of the vertebrate paleontology collections and his time-lapse video of the fossil inventory “blitz” prior to the PD; and M. Barboza, for her social media coverage. This PD was supported by National Science Foundation Advancing Informal STEM Learning grant #1322725 (DRL).

Jeanette Pirlo (jpirlo@flmnh.ufl.edu) is a PhD student at the Florida Museum of Natural History and in the Department of Biology at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. Bruce J. MacFadden (bmacfadd@flmnh.ufl.edu) is distinguished professor and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, in Gainesville, Florida. Eleanor E. Gardner (Eleanor.gardner@ku.edu) is the outreach and engagement coordinator at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum in Lawrence, Kansas. Victor J. Perez (victorjperez@ufl.edu) is a PhD student at the Florida Museum of Natural History and in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. Denise Porcello (deniseporcello@gmail.com) is a second-grade elementary teacher at Brookside Elementary School in Dracut, Massachusetts.