Feature

Imagine Your STEM Future

Connected Science Learning January-March 2019 (Volume 1, Issue 9)

By Sara Kobilka, Shalane Simmons, and Michelle Higgins

If you were walking down a hallway at Desert View High School in Tucson, Arizona, on an early morning last February, flying projectiles and excited voices might have been a cause for concern; however, these were neither paper airplanes nor spitballs flying through the air. Instead, groups of high school girls were dropping eggs carefully wrapped in protective designs of their choice. These girls, participants in the Imagine Your STEM Future (IYSF) program, were completing a common activity in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) programming—but these girls had female engineer mentors supporting them in the build process and connecting it to their work as employees of Raytheon Company.

Patching a leaky pipe

The idea for IYSF came from Raytheon leadership who saw a pipeline issue for their future workforce. At the time, Raytheon supported multiple STEM programs in the Tucson community for students from kindergarten through 12th grade. Many girls with potential in STEM were engaged and participating in STEM programs in elementary school. As they moved through middle school and into high school, however, they were dropping out of programs and opting out of upper level math and science classes. Upon graduation, this lack of foundational classes left them unprepared to major in STEM degrees and subsequently enter the STEM workforce. Leaders at Raytheon were also reading literature describing this trend on a national scale and were concerned about their return on investment for the programs they were funding. Concurrently, Raytheon executives were working on new business contracts and realized that, in five to 10 years, they would need to hire a large number of new engineers.

In 2010, after convening with existing community partners, Raytheon found a new informal science education partner in the Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona (GSSoAZ). The Girl Scouts Leader Experience model brought in the leadership and girl-driven focus that Raytheon leaders felt would be more successful than one-off engagement events. The Girl Scouts of the USA (GSUSA) also already had resources for the STEM activities and trained staff who could lead girls. The current GSSoAZ Director of STEM and Hispanic and Social Justice Initiatives, Michelle Higgins, was chosen to codirect the program in partnership with a codirector from Raytheon. As the program continued to grow and the need for staffing became critical, the nonprofit Southern Arizona Research, Science, and Engineering Foundation (SARSEF) stepped in to support. Since inception, IYSF has used the GSUSA model of girl-driven activities, while SARSEF is now the official nonprofit partner.

Desert View High School was chosen to house the program because its enrollment includes a large number of girls traditionally underserved in STEM and because Raytheon had an existing relationship with the school. Desert View is part of the Sunnyside School District and is located in southern Tucson near the Davis-Monthan Airforce Base and Raytheon’s Tucson site. This Title I school serves students in ninth through 12th grade. More than 80% of the students are non-Caucasian, with 72% Hispanic or Latino, 5% American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 4% Black or African American (not Hispanic). Nearly 80% of students qualify for free or reduced lunches (SFA 2012). The school places a large emphasis on college and career readiness, a perfect combination to achieve Raytheon’s goal of inspiring and supporting youth to pursue STEM education and eventually STEM careers.

The program started with the two codirectors, five Raytheon mentors, and one classroom of 25 freshmen. By the 2017–2018 school year, the program’s growth (four classes, more than a dozen mentors and more than 100 high school girls) necessitated the addition of a part-time program coordinator who was hired by SARSEF and whose salary was covered by Raytheon funding. SARSEF’s Raytheon funding also covered the cost of supplies and field trips, while the salaries of codirectors and high school teachers are covered by their respective employers.

Goals for young women in the program include increasing interest in STEM learning and STEM careers, increasing self-concept and self-efficacy in STEM, improving collaboration skills, and preparing them for leadership roles in the future, both in and out of STEM. The multifaceted program incorporates research-based strategies that have been shown to have a significant impact on high school girls: use of trained mentors and role models (Mostache, Matloff-Nieves, Kekelis, and Lawner 2013; Liston, Peterson, and Ragan 2008; Kobilka 2017), girl-led activities (Girl Scouts of the USA 2008), and a focus on growth mindset (Dweck 2000).

Current program overview

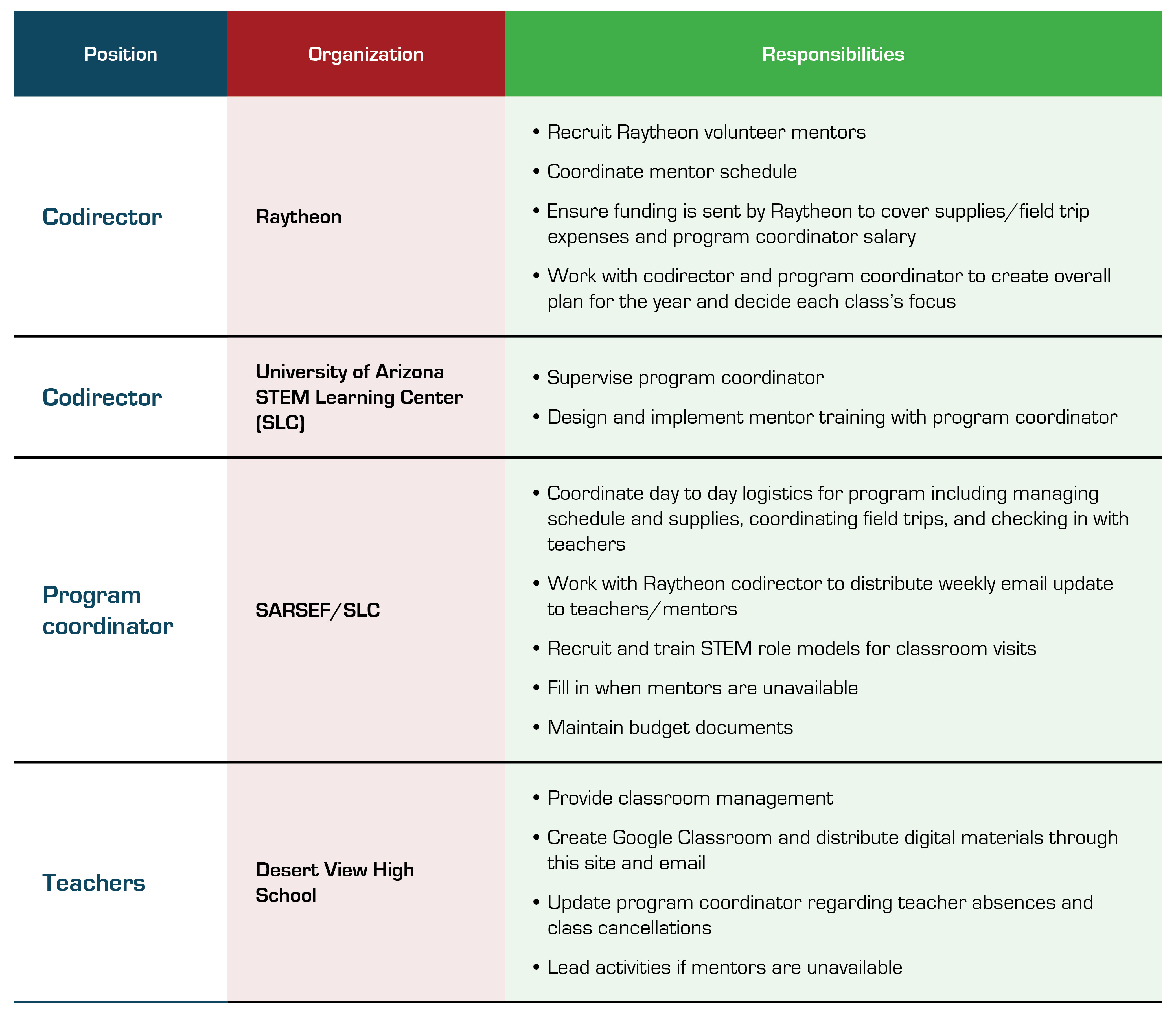

This fall, IYSF entered its seventh year, with five classes spanning from freshmen to seniors encompassing 140 participants and 24 Raytheon mentors. Classes meet during the school day and are graded on a pass/fail system based on participation. The program is a unique partnership between Desert View High School, the University of Arizona STEM Learning Center (SLC), Raytheon, and SARSEF. This collaborative effort brings together formal education, informal practices, and industry, highlighting the strengths of all partners. A list of responsibilities of the primary leadership team can be found below (Figure 1). The leadership team is cross-trained and able to fill in for others. While a teacher is present in each classroom, the activities are primarily led by one or more female mentors from Raytheon. Any given class period is a combination of hands-on STEM activities, reflective group conversations, or role model videos or visits. Each element of the program has been chosen based on best practices for maximizing impact on girls’ interest and persistence in STEM.

I look like a STEM professional

Research has shown that interaction with STEM mentors plays an important role in helping girls build the critical STEM identity that supports interest and persistence, leading them to a future STEM career (Liston, Peterson, and Ragan 2008). Girls have an easier time connecting to female mentors (Hill, Corbett, and St. Rose 2010). Female Raytheon mentors are recruited by the Raytheon codirector through company newsletters, postings, and word of mouth. They are trained before the school year begins by the SLC codirector and the program coordinator regarding best practices for working with girls (Billington et al. 2018; Kekelis and Joyce 2013; Kobilka 2017) and how to create an inclusive environment (NCWIT 2014). This type of training has been shown to play a critical role in the success of STEM professionals engaged with the general public (Tisdal 2011) and was designed using readily available resources (see references). A check-in session over lunch at Raytheon is held during the middle of the first semester to provide continued support and gather feedback from mentors regarding their experience to that point. Midyear and end-of-year online surveys are also distributed to mentors and are analyzed by the program coordinator and codirectors to determine any changes that may be needed in the future.

Mentors are asked to commit to an entire school year, with most visiting the same class weekly or every other week. Due to the frequency of the visits and the large class size, the Raytheon volunteers’ interaction with the young women is a hybrid of mentorship, with emphasis on relationships and one-on-one conversations, and a role model—someone girls can look up to and whose footsteps they can aspire to follow.

The rotating schedule of mentors means that communication is key to ensure continuity, especially for multiday projects. When the program began, the codirectors were in the classroom with mentors on a regular basis and were able to keep the projects moving. As the program expanded to its current five classroom arrangement, a structured email communication system was developed. The Raytheon codirector and program coordinator send an e-mail to all mentors, teachers, school administrators and program leaders on Thursday or Friday to explain the activities and projects scheduled for the following week. Activity instructions and video links are included. After a mentor completes their assigned class period, they “reply all” to the original email with a quick update regarding what was accomplished and what the girls are ready to work on the following day. This line of communication has been critical to the program’s success. It allows mentors to arrive prepared and to focus their energy on connecting with and supporting girls, and to be aware of any unexpected delays or cancellations.

IYSF codirector Michelle Higgins says that these female mentors play a unique role in the girls’ lives, as “the girls may listen to and accept their advice in a way that is different than listening to their teachers, parents, and counselors.” Rather than being authority figures, they are seen as guides who are not telling the girls what to do, but rather providing resources and a sympathetic ear. These mentors have the opportunity to build close relationships with the girls in their class over the course of the year. One of the inaugural mentors, Karen, volunteered two to three times per week and built lasting relationships with many of the girls in IYSF. In 2017 end-of-year surveys, girls frequently mentioned the profound impact she had on the group. One participant reported, “I connected with Karen most because she always asks how I am doing, what I think and feel about STEM. It made me feel like I matter in this program and that we have a say in this.” Another girl said, “Karen was very nice and intrigued with what we did, she told us about her life and was very helpful in explaining the possibilities and opportunities available in science-related jobs.”

Visits from other local female STEM professionals and role model videos introduce participants to an even wider range of women in STEM careers, with the goal that all girls will see someone who looks like them or shares their background. This also helps broaden girls’ perspectives on what opportunities exist for women in STEM and the paths women take during their careers. Female STEM professionals are recruited by the program coordinator and asked to watch a short online video and go over detailed instructions about the program to prepare for their visit. This type of preparation has been shown to increase the success of STEM professional interaction with students given the short length of their visit (Kekelis and Gomes 2009; Kobilka 2017). This is coordinated via emails. An excellent source of role model videos for this particular audience was the SciGirls Stories: Latinas at Work and the SciGirls Profiles, created by Twin Cities Public Television. These videos show real women from a wide variety of STEM careers. The women talk about the different paths they have taken to their careers, why they find their jobs fulfilling, and their interests outside of work. In the Latinas at Work videos, the women speak in both Spanish and English, which is especially empowering for the girls from Desert View High School, some of whom are bilingual and are not necessarily hearing a message that this can be an asset for a future career.

Collaboration for communication and community building

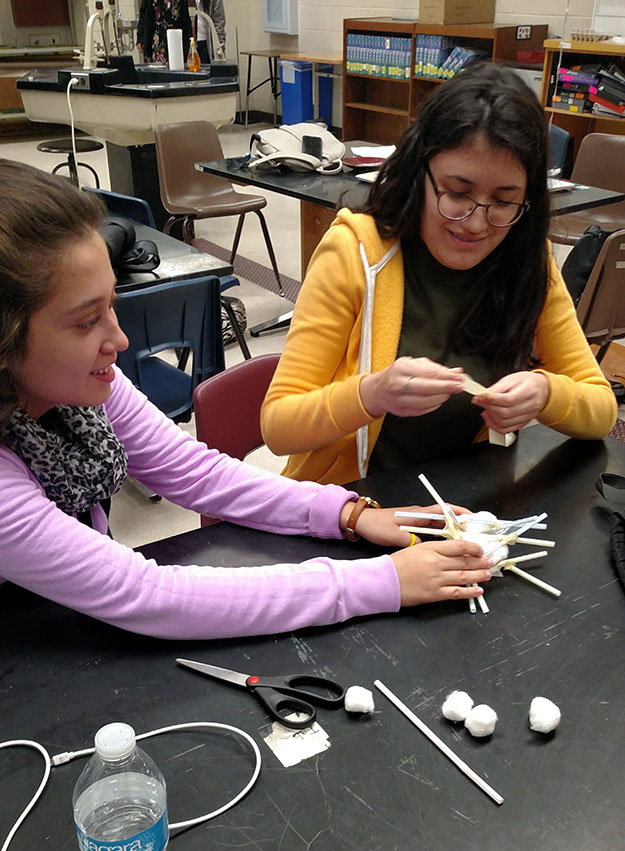

Girls participate in a variety of hands-on STEM activities over the course of the school year. The majority of these chosen activities have been designed by nationally recognized informal science education programs, including SciGirls, Design Squad, and Girl Scouts. Most girls enter the program in their freshman year and continue through senior year, so different instruction methods are used to engage girls with a range of ages and prior experience. In freshmen classes, we focus on hands-on learning experiences as many girls have limited experience with engineering projects in particular. IYSF leaders seek to find a balance between providing an appropriate amount of instruction and still allowing for and promoting creativity and critical thinking (Billington et al. 2018). Through the engineering design process, girls begin to build STEM skills such as designing, building, and prototyping, but more importantly for this program, learn communication and organization skills as they work in small groups. The group work also fosters a sense of community amongst the girls. The design/build/test portion of the activities takes approximately three days, with the following three days spent on preparing and presenting or submitting Project Recaps. Recaps include reflection on each group’s successes and opportunities for growth, giving girls space to think critically about collaborative work as well as practice communication skills. The Project Recap is also a time when mentors can share their own journey to a STEM career and their daily challenges in a collaborative work environment. These types of learning and communication opportunities rooted in informal science education pedagogy may not otherwise be available to these girls (Fenichel and Schweingruber 2010). Desert View High School Principal RoseMary Rosas says “[IYSF] has allowed our scholars to connect these content areas (science and engineering) to real-world activities that enlighten and engage our students in projects that are atypical of high school curriculum.”

One such experience was completed over the course of the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 school years by the sophomore classes. They built a wood-framed greenhouse using water bottles strung on fencing wire for the walls. The sophomore year is traditionally when IYSF girls participate in larger, longer projects—in this case, one of the longest projects ever created within the program, which took months to complete. The greenhouse brought male mentors into the program to gauge the girls’ ability to connect with a more diverse pool of mentors. As with the female mentors, training was provided prior to their arrival and emphasis was placed on letting their girls do as much as possible on their own. This included running power tools under direct supervision and wearing proper safety equipment. Male mentors also encouraged the girls to think like an engineer throughout the building process. Feedback regarding this trial run with male and female mentors was completely positive for all parties involved, and will serve as a model for future large projects that require assistance of adults with specific skillsets. The sophomore teacher expressed a great deal of appreciation for how the male mentors worked with and supported the girls throughout the building process. She felt that they provided encouragement while challenging the girls to try new things, building their confidence and teaching them carpentry skills few had prior to the class.

Self-concept and advocacy

By the time participating girls are juniors and seniors, the program’s focus turns to providing opportunities for leadership and self-advocacy as well as final preparations for college. Older students assist teachers with the process of recruiting eighth-grade girls from feeder middle schools to participate in their freshman year. These oldest girls also visit local elementary schools with STEM activities they have designed to increase interest and self-confidence in STEM in young girls and boys.

Reflective group conversations are used strategically throughout the school year. Currently, at least one class period per week begins with “Circle Time.” The girls stand in a large circle, taking turns answering a question posed by the mentor. Sometimes, circle questions are a lighthearted means of checking in (What type of weather best describes how you’re feeling today?), but others dig deeper into current events. During the 2017–2018 school year, girls discussed topics such as the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, and the “Red for Ed” movement and corresponding teacher walkouts. These group conversations provide the girls with a chance to share their opinions and advocate for things that are important to them. It also supports the effort to build a sense of community as girls find others who share similar feelings.

In one of the first activities of the school year, all girls watch a short video about the #ILookLikeAnEngineer campaign and are challenged to work in small groups to create their own #ILookLikeASTEMStudent video. The IYSF program coordinator created instructions and a rubric for evaluating the videos, placing an emphasis on videos that emphatically communicate the girls’ perspective on the state of women in STEM. Girls, teachers, and Raytheon mentors vote on the video with the most impactful message, and its creators are invited to speak at a prestigious luncheon hosted by the Tucson affiliate of the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Last spring, select girls also traveled to the Arizona State Capitol, where they spoke with lawmakers about the importance of supporting STEM education, especially opportunities for girls and other traditionally underserved groups. They have been invited to visit again this spring.

Looking to the future

As with many programs, especially ones embedded within the school day, time is the most challenging issue. Starting in the 2016–2017 school year, the IYSF class was scheduled to meet during a period called CC/PREP (College and Career Preparation) which lasts approximately 30 minutes. Announcements and the Pledge of Allegiance are also conducted during this period, shortening the time even further. Planning for what could be realistically accomplished during this short time period was a constant challenge. Working with school administrators, we have been able to partially address this issue with our two freshman classes. Girls were scheduled with the same teacher for the period prior to CC/PREP. This allowed teachers to have mentors work with the girls for 30 minutes at the beginning of the school day, uninterrupted by announcements and at a time of day that fits better with many mentors’ work schedules.

The 2018–2019 school year offered a new opportunity to deal with the limited time frame. Rather than meeting during CC/PREP, an elective Career Exploration class was scheduled for first period and reserved for girls who had participated in the IYSF program their freshman year. The class’s timeframe and longer class period of almost 90 minutes allowed for additional visits from STEM professionals from the wider community as well as field trips to companies with a strong STEM workforce. Whenever possible, STEM role models were provided with basic training. Materials provided by the University of Arizona’s College of Education were modified by the program coordinator for use in the classroom and mentors were able to spend more time focusing on the girls’ specific STEM interests. Videos of STEM role models were incorporated more regularly, and the Fab Fems database of female STEM role models from across the country was used to find women who could participate in a video call with the girls during their class period. At the end of the school year, we will be evaluating the success of this new format to see if it will be continued next year.

Research has shown that if a mentoring relationship is going to have a lasting impact, a connection must be made between the student and mentor. The format of our program can make that difficult at times for the mentors. Some classes have more than 25 girls, and not all mentors are able to visit on a weekly basis. This makes it difficult for mentors to learn the names of the girls, a foundational element of building a connection. End-of-year surveys from the 2017–2018 school year indicated that this lack of connection led to a negative experience with mentors for a portion of the girls. For this school year, a new beginning-of-the-year project was added in hopes of improving this situation. All girls, mentors, and teachers created a basic Google slide following a template. The slide format, in combination with the spoken presentation, was chosen in order to present the information in multiple ways for mentors with different learning styles. Each slide included a recognizable picture of the girl; their name, grade, and teacher; and two images that represent things that they are passionate about. These slides have been available to mentors throughout the school year to refresh their memories prior to visiting the class. It also gave the participants the opportunity to get to know one another better and begin the critical task of building cohesion amongst the group. All girls and mentors presented their slide to the class as a way of introducing themselves. End-of-semester and end-of-year surveys of both students and mentors will be analyzed to see whether the project has had its intended impact.

Lasting impact is one of the program’s goals. Many of our graduates are currently in college, and a few that maintain contact with IYSF mentors are majoring in the fields of mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, cyber security, and physiology. We are actively seeking ways to more formally stay in contact with them following graduation. One such effort, piloted this fall, includes leading girls through the process of creating effective professional LinkedIn profiles to pursue their college and career goals. Access to active profiles could assist with future connections for surveys and focus groups. We also will be reaching out to IYSF alumni at the University of Arizona and nearby Pima Community College to hold focus groups and possibly bring them in as role models for current students.

The IYSF leadership team is in the midst of an in-depth strategic analysis of the evolution of the program over the last seven years. We are looking at what modifications should be made to the logic model behind the effort and researching new best practices for engaging girls and project management. Our team is focused on maximizing our impact given the time and resources we have available. There is also a desire on Raytheon’s part to expand this program into additional schools. An updated framework and support materials are critical to enable expansion and achieve success.

Sara Kobilka (sara.skell@gmail.com) is program manager at the University of Arizona STEM Learning Center in Tucson, Arizona. Shalane Simmons (shalane.simmons@raytheon.com) is community relations manager at Raytheon Company in Tucson, Arizona. Michelle Higgins (mlhiggins@email.arizona.edu) is associate director at the University of Arizona STEM Learning Center in Tucson, Arizona.