Emerging Connections

STEM Pathways

Building a STEM Learning Ecosystem

Connected Science Learning March 2016 (Volume 1, Issue 1)

By Abby Moore, Beth Murphy, Melanie Peters, and Steven Walvig

STEM Pathways is a collaboration between five Minnesota informal STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education organizations—The Bakken Museum, Bell Museum of Natural History, Minnesota Zoo, STARBASE Minnesota, and The Works Museum—working with Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) and advised by the Minnesota Department of Education. STEM Pathways (logo shown in Figure 1) aims to provide a deliberate and connected series of meaningful in-school and out-of-school STEM learning experiences to strengthen outcomes for students, build the foundation for a local ecosystem of STEM education stakeholders, and create an innovative model that demonstrates how informal STEM education (ISE) organizations can work together.

Figure 1

STEM Pathways logo

In 2012, STARBASE Minnesota, a Twin Cities informal STEM education provider, completed a long-term follow-up study, conducted by Wilder Research, of its program participants. The findings from this study pointed to the need to find ways to sustain and build on short-term program impacts over time, especially for low-income populations with limited access to ISE opportunities (Mohr and Mueller 2012). The study included an inventory of local STEM programs that identified other ISE field trips and outreach programs serving MPS students that could be part of a connected series of STEM programs. The Bakken Museum, Bell Museum of Natural History, Minnesota Zoo, STARBASE Minnesota, and The Works Museum were identified as strategic partners. All agreed to participate in a three-year pilot collaboration to develop a comprehensive and connected pathway of STEM experiences, offered in partnership with MPS. The enthusiasm of the five partner ISE organizations that formed STEM Pathways was matched by that of MPS STEM specialists, who were interested in strengthening the district’s relationship with community partners to more effectively support and accelerate the district’s STEM learning goals.

The need for a system of connected—rather than isolated—STEM learning experiences was echoed by Santi Bromley, an elementary MPS teacher for over 20 years. Bromley knows firsthand the power of ISE experiences in strengthening STEM learning and bringing STEM to life for her students: “I took advantage of every learning opportunity I could for my students, including going to the Bell Museum, STARBASE Minnesota, and the Minnesota Zoo, and I saw the huge impact that authentic STEM learning had on my students. The opportunity for my students to be scientists and engineers in real-world situations and use resources and technology was something that I couldn’t easily replicate in the classroom. However,” she noted, “these experiences, as fantastic as they were in building enthusiasm for STEM and enhancing STEM learning, were just bursts of STEM for relatively short periods of time, and the enthusiasm was hard to sustain over the months between experiences. As great as these experiences were for my students, the lack of connection between them was the missing piece.”

Program Overview

The STEM Pathways collaboration officially began during the 2013–2014 school year. The first year of the pilot study was devoted to planning, followed by two years of implementation in schools (2014–2015 and 2015–2016). Key activities during these three years included:

- establishing a steering committee (see sidebar) to provide strategic direction;

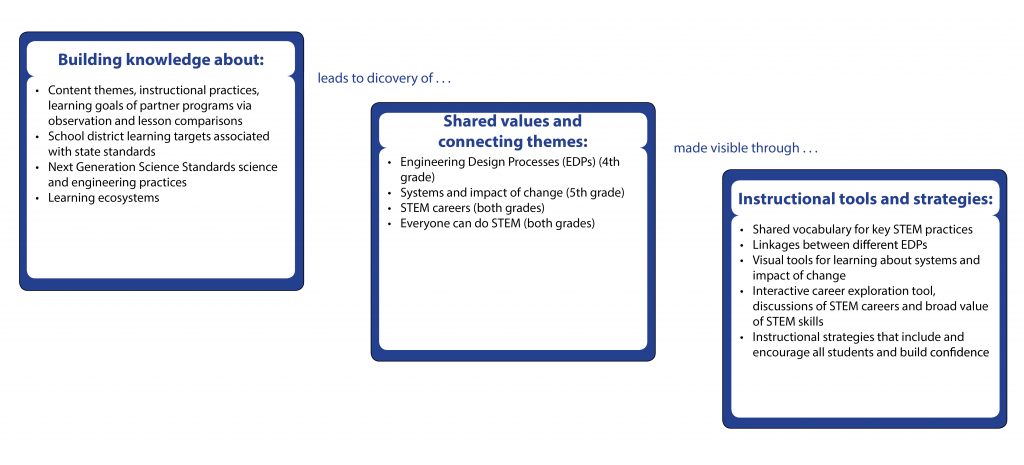

- discovering and developing shared values, knowledge, key messages, instructional tools, and approaches (see Figure 2);

- implementing programs with all fourth- and fifth-grade classrooms in six MPS schools; and

- conducting research and evaluation to inform ongoing improvements to programs and the collaboration model, measure impact, and inform future directions.

A key activity of the implementation phase was understanding the impact of STEM Pathways on MPS students, schools, teachers, and the district, as well as ISE organizations’ programs and staff. As the three-year pilot draws to a close, the next phase for STEM Pathways will include using research and evaluation findings to make evidence-based improvements to the program, collaboration model, and strategic plan to expand and sustain the collaboration.

Figure 2

The STEM Pathways collaboration process includes knowledge building to discover shared values and connecting themes that are made visible in the form of key messages and instructional tools (click to enlarge)

Audience

Currently, STEM Pathways works with MPS to serve all fourth- and fifth-grade classrooms at six MPS schools (about 900 students, 64% of whom are low-income students and 78% of whom are students of color). In the near future, STEM Pathways intends to expand to more schools, grade levels, and/or ISE partners. “STEM Pathways couldn’t have come at a better time,” said Joe Alfano, a former MPS district elementary STEM coordinator, who was looking for ways to strengthen connections with community organizations and better align their programs with district goals. The leadership and advocacy of the district-level STEM department has been a critical feature of the STEM Pathways collaboration in terms of, for example, communicating and advocating with teachers and principals, enabling research and evaluation, and finding synergies between informal and formal STEM education to amplify learning value.

Program Development

The founding ISE partners were selected because they each had a history of serving fourth- or fifth-grade classrooms in MPS, with each organization already providing programming that to some degree connected its unique mission to MPS’s science and engineering curriculum and Minnesota’s state academic standards. What did not exist, however, was a substantive system to:

- promote and sustain collaboration among ISE organizations,

- ensure efficient and consistent two-way communication with the MPS school district,

- facilitate high-level alignment with district curriculum and priorities,

- connect ISE STEM learning experiences to one another over time, or

- provide students with a cohesive set of in- and out-of-school STEM learning experiences.

Deliberate knowledge-building was therefore an important planning-year activity for the STEM Pathways partners. This process, illustrated in Figure 2, included opportunities for MPS representatives, ISE instructors, and leadership staff from all partners to:

- learn about the participating ISE organizations and programs,

- explore important topics in formal and informal STEM education,

- discover authentic overarching themes and concepts connecting the STEM Pathways partner programs, and

- develop tools, strategies, and messaging that would help students and teachers experience STEM Pathways programs as a set of interconnected experiences that support, amplify, and bring greater meaning to their classroom learning.

One of the first challenges we faced was finding authentic overarching themes and concepts to connect the partner programs, which were developed by the individual ISEs for MPS before the STEM Pathways partnership began. Abby Moore, the Minnesota Zoo’s school programs supervisor, acknowledged that getting started was challenging, especially because each ISE partner started with a stand-alone, pre-existing program. “On the surface, it was hard to imagine how to link three seemingly unrelated programs—one about Minnesota ecosystems, another on designing a mission to Mars, and a third about population decline in honeybees,” Moore said. In collaboration with the MPS K–8 STEM Curriculum Specialist, we started drilling down into the concepts covered in each program and how they supported Minnesota’s state academic standards and the district’s learning targets. By developing a deeper understanding of MPS’s science and engineering curriculum and each other’s programs, MPS representatives and ISE instructors designed program sequences for each grade (see Figures 3 and 4), including connecting themes and instructional tools to complement and enhance what teachers were doing in the classroom.

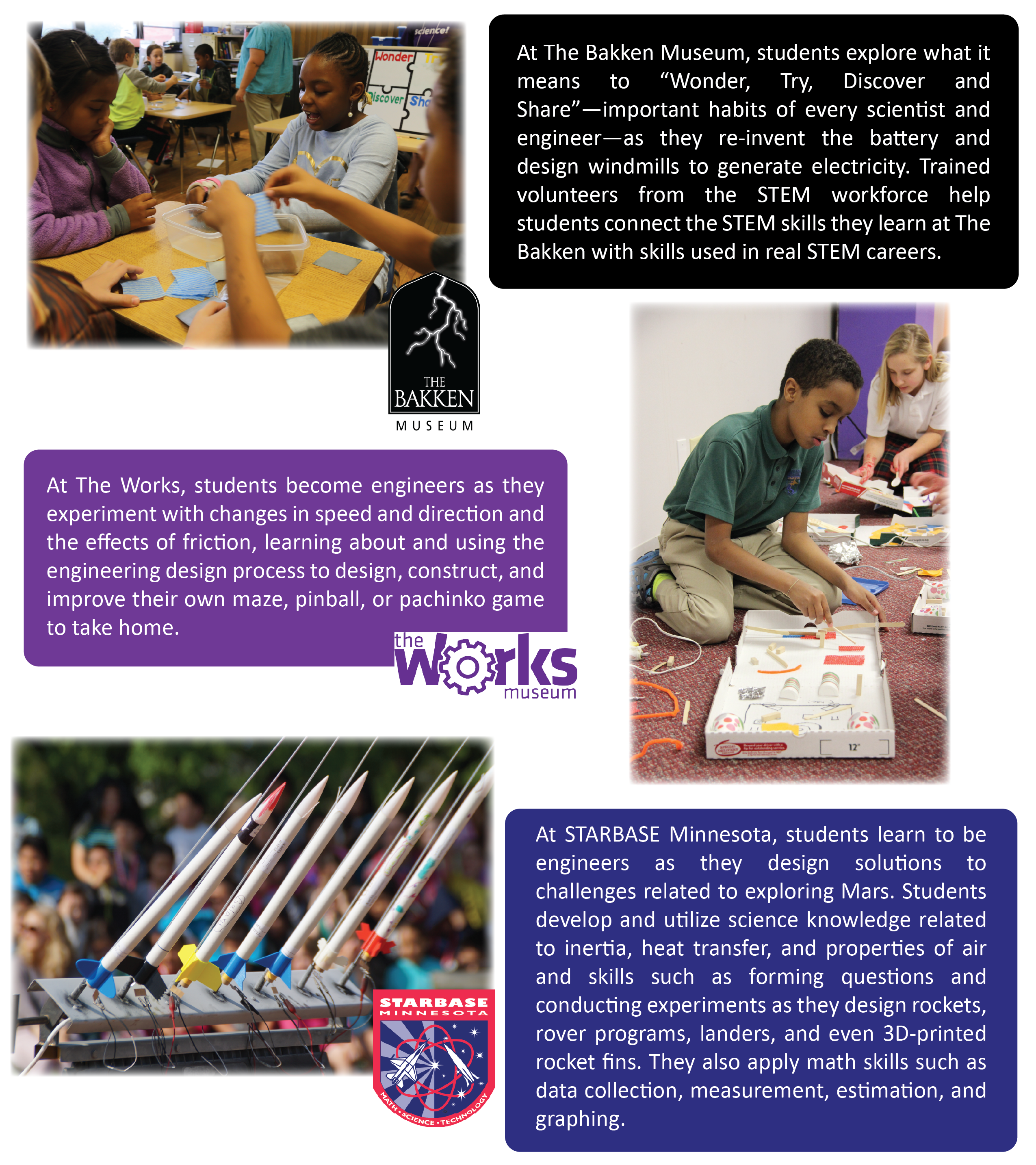

In the fourth-grade program sequence (see Figure 3), MPS representatives and ISE instructors reinforced the science and engineering practices described in A Framework for K–12 Science Education (NRC 2012) by providing students with opportunities to experience these practices across programs and in different contexts, while exploring real-world issues. For example, MPS fourth graders study electricity and magnetism in their classroom via the Full Option Science System: Energy and Electromagnetism module. The Bakken’s program takes place early in the school year, and it is designed to introduce science and engineering practices, electricity, and magnetism to students to prepare them for the material they will soon study. The fourth-grade sequence also provides students with examples of STEM careers that use science and engineering practices.

Figure 3

Fourth-grade program sequence

The fifth-grade program sequence (see Figure 4) builds on the fourth-grade sequence by continuing to reinforce science and engineering practices and STEM careers, while introducing a new connecting theme: systems and systems change. “As a fifth-grade team, we tried to imagine how our distinct programs could meaningfully share a ‘big idea’ that we could all highlight and a significant common theme emerged: systems and systems change in natural and designed environments,” explained Moore. It is serendipitous—and significant—that this common theme is also a crosscutting concept in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS Lead States 2013). For example, at the Minnesota Zoo, students explore how changes such as clear-cutting, cutting down a large stand of trees, can impact a food web. At STARBASE Minnesota, students experiment with how changing components of a design can impact a product, such as a rocket or Mars colony. At the Bell Museum, students investigate the important connections between honeybees and food, and how natural and human-influenced changes to the environment and climate impact honeybee populations.

Figure 4

Fifth-grade program sequence

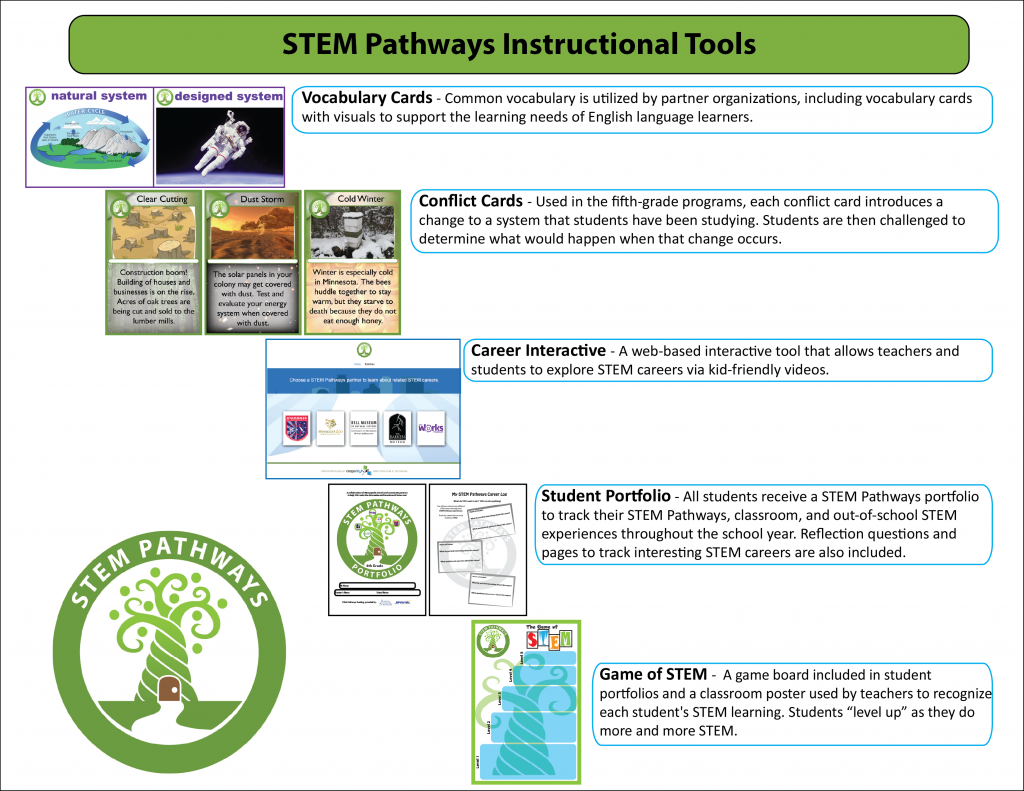

Instructional Tools

The STEM Pathways collaboration uses a variety of branded instructional tools to illustrate and reinforce connections between programs, build student confidence, and help students and teachers explore STEM careers (see Figure 5). Vocabulary cards are embedded in learning experiences across programs at each grade level to reinforce important concepts, skills, and ideas (e.g., helping fifth graders develop a conceptual understanding of systems) (see Resources for examples). “Conflict cards,” which are also for fifth graders, reinforce and illustrate system changes, prompting a deeper understanding of the complexities and dynamic nature of systems (see Resources for examples).

Additionally, STEM Pathways provides teachers and students with an online STEM Pathways Career Interactive to expand their understanding of STEM careers. Each program is associated with a collection of DragonflyTV videos of STEM professionals explaining what they do (click here for an example). Teachers are also given student portfolios for the fourth-grade and fifth-grade sequences (see Resources); each contains STEM-based activities, reflection exercises, and a “Game of STEM” to track students’ STEM learning experiences throughout the year and encourage them to continue and deepen their STEM learning. As one ISE instructor said, “These tools are a product of our collaborative process and have become critical to helping us communicate the connection between our programs and the overarching themes and concepts we want to connect for students and teachers.”

Figure 5

STEM Pathways instructional tools are designed to make connections between programs, reinforce important shared concepts, build student confidence, and explore STEM careers (click to enlarge)

Evaluation Findings

The formal evaluation for STEM Pathways is being conducted by Wilder Research and, during the second program year (2014–2015), including surveys of students, interviews with school and district leaders, and interviews with both leadership and lead instructors from partner organizations. In the third year (2015–2016), evaluation activities will also include student and teacher focus groups and a teacher survey.

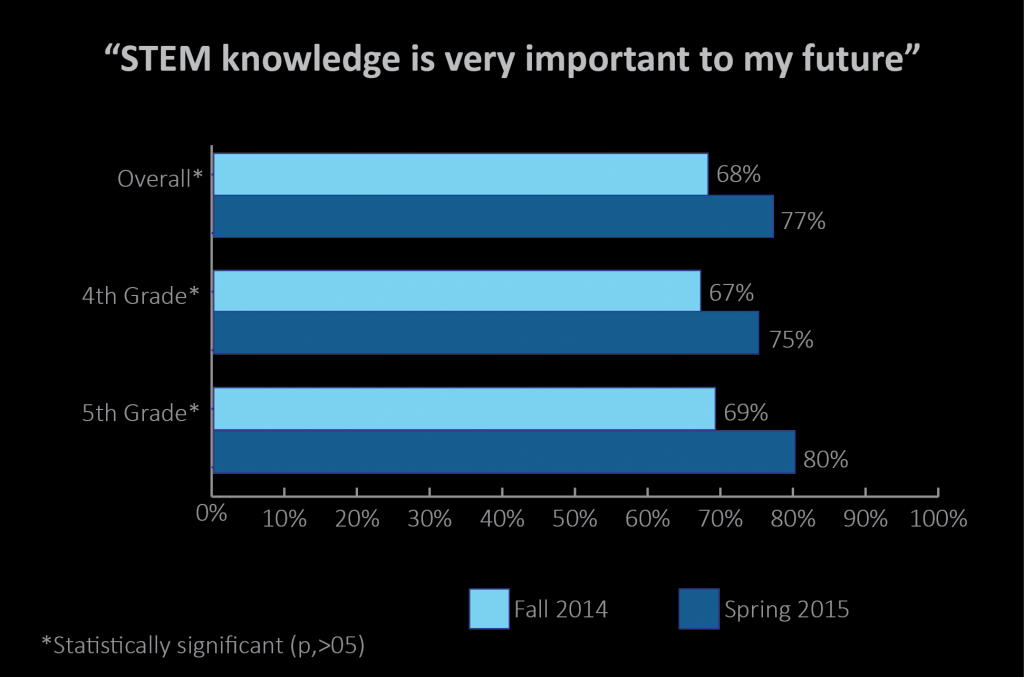

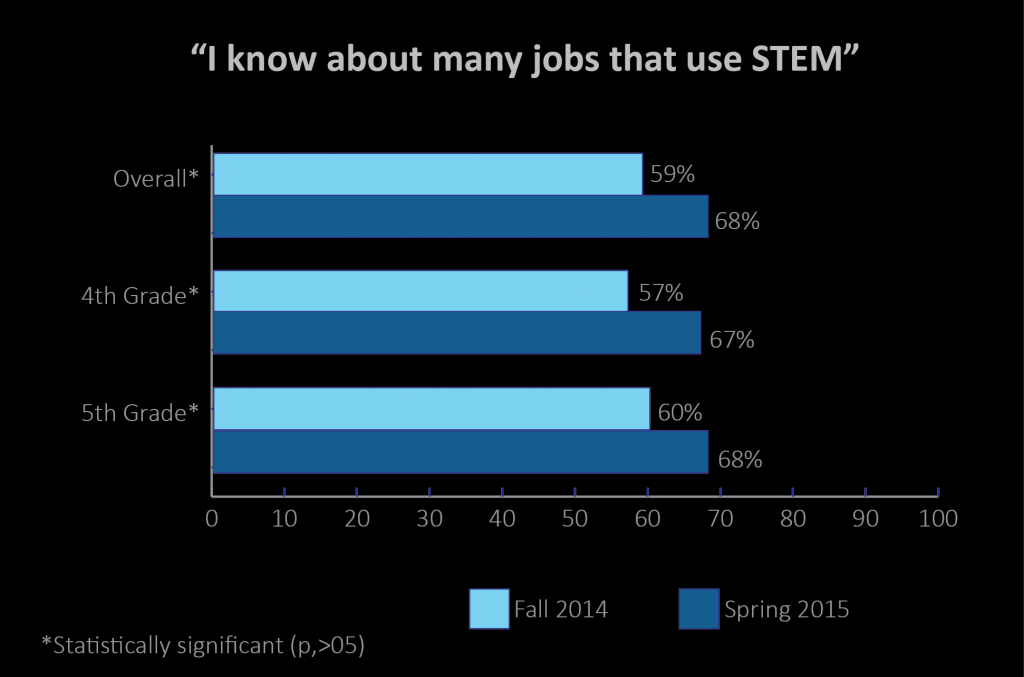

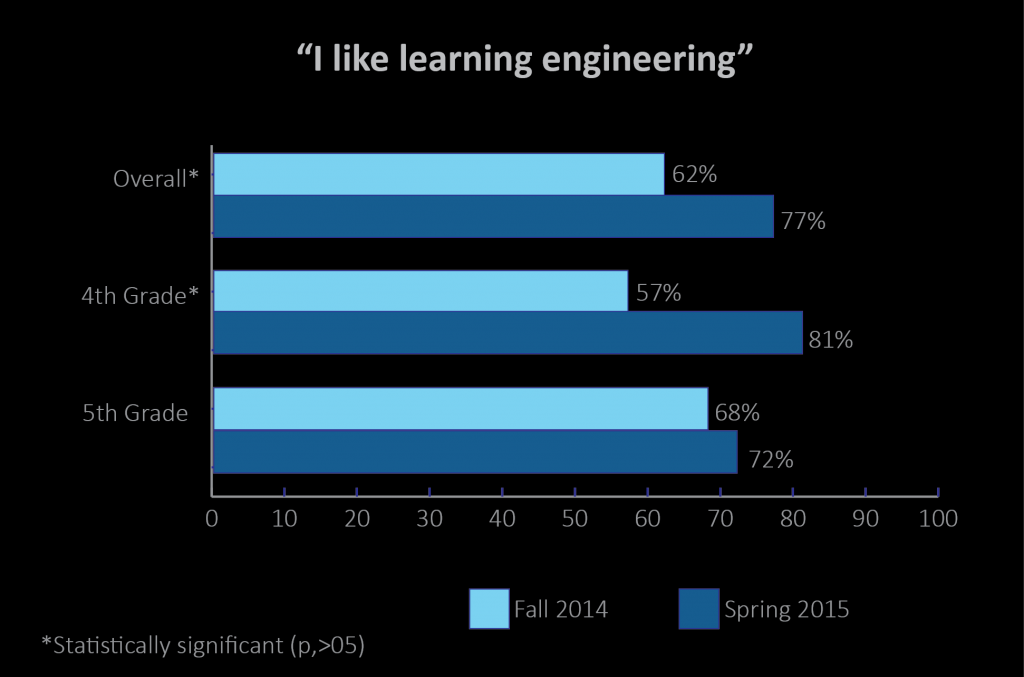

Pre- and post-surveys of participating fourth- and fifth-grade students strive to measure changes in students’ self-reported awareness, interest, and learning in STEM; confidence in their STEM abilities; and interest in STEM-related careers. The Bakken Museum’s experience measuring students’ dispositions toward science—which The Bakken calls “science assets”—in combination with the experience of other partners and research from the field contributed to the development of these evaluation tools. Matched pairs of pre- (fall 2014) and post-surveys (spring 2015) were completed by approximately 700 STEM Pathways students (85% of participating students). Evaluation findings showed a significant, positive change in students’ pre- to post-responses to the following statements: STEM knowledge is very important to my future, I know about many jobs that use STEM, and I like learning engineering (Figure 6a–c).

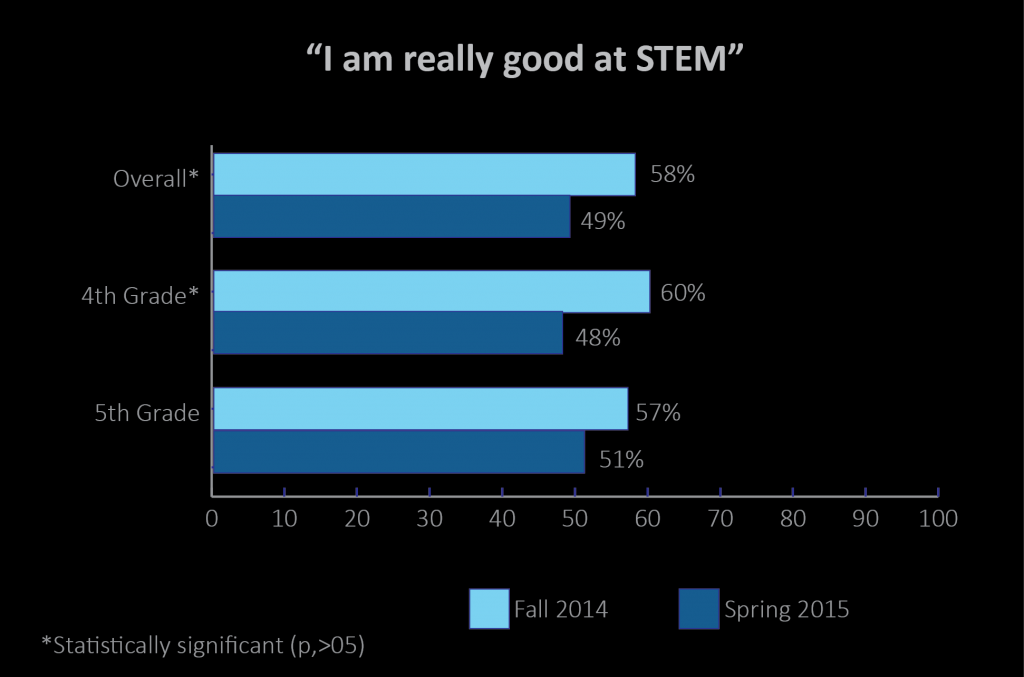

Of course, evaluation findings also raise questions and highlight opportunities for greater impact and further growth. For example, although students reported greater awareness of STEM careers and knowledge that STEM education is important, they demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in their STEM confidence, indicated by their response to the statement: I am really good at STEM (Figure 6d). Despite this decrease, student response to the statement, I would be good at a job that uses STEM, did not change significantly from fall to spring (slightly over 50% agreed at both time points). At this point, what this means and what factors related or unrelated to STEM Pathways contributed to this decrease are purely speculation. We plan to conduct responsive interviews with small groups of students in early 2016 to learn more about what students think it means to be good at STEM and how they define success, among other issues.

Figure 6

Students demonstrated statistically significant positive change regarding their (a) perceived importance of STEM knowledge to their futures, (b) awareness of STEM careers, and (c) enjoyment of learning about engineering. However, student survey findings point to a possible decrease in confidence in STEM abilities (d).

a.

b.

c.

d.

Findings also indicated that the proportion of fourth and fifth graders frequently engaging in STEM-related activities outside of school did not change significantly from fall 2014 to spring 2015. Slightly fewer than half of students in both the fall and spring agreed that they knew about many STEM-related activities outside of school. The only demographic group to have an increase in agreement with this item from fall to spring was Caucasian students. However, over 60% of all students in both fall and spring agreed that they would like to do more STEM-related activities.

All participating MPS teachers were invited to attend an informal focus group in 2015. Participating teachers indicated that one of the most impactful elements of the STEM Pathways program is how it connects school-based and community-based learning experiences. All of these experiences build upon each other and work toward teaching science and engineering standards, in addition to helping students make personal connections with STEM and build awareness of STEM careers. This is echoed by MPS leaders, one of whom stated, “I think any time you have community partners that are working together for the benefit of your students, the staff, and just making the Minneapolis Public Schools a richer place to be and grow, there’s endless benefits. I mean these relationships are what build a community. We can be MPS, but it’s really the rich community around us that makes us special.”

MPS principals and district leaders consistently valued STEM Pathways and identified its benefits as increased student engagement, support for teachers, and alignment of informal education experiences with state standards (see the STEM Pathways Teacher Guide in Resources for examples of alignment to standards). According to one principal, “It is an experience that provides our students with real-time STEM experience. Our students will walk away with an idea of all the possibilities of what a future in the STEM world is about—how it is applicable in everyday living—and possible career tracks and a love for STEM. For teachers, it is about observing how STEM can be embedded every day in teaching and learning.”

Challenges were also identified by both principals and district leaders. Principals noted lack of funding for buses and site visits as the primary struggle for participating schools. MPS district leaders also noted that district-wide expansion would be important for long-term sustainability of STEM Pathways in MPS. If STEM Pathways were to remain at the same scale as it is during this pilot phase, STEM Pathways would not align with the district’s goal of serving all students because it only provides the experience for a fraction of the district’s fourth and fifth graders. Out of these challenges came several suggestions for improvement including securing funding for buses, involving teachers in a kick-off professional development meeting at the beginning of the year, and giving teachers more opportunities to give feedback on their experiences.

Reflections and Lessons Learned

A significant outcome of the three-year pilot phase of STEM Pathways is the consistent belief on the part of partners in the value, power, and potential of authentic collaboration across informal and formal STEM-education organizations to make a difference for students. The nature of STEM Pathways’ collaborative effort is new and different and represents a paradigm shift for how ISE organizations work with each other and with formal education. Partners believe this model of connecting STEM experiences for and with schools will make a positive difference for students in terms of their access, enthusiasm, and academic achievement in STEM, as well as their awareness of and interest in STEM careers. Preliminary evaluation findings and anecdotal evidence point to this potential; Wilder Research’s final study will identify conditions and practices for effective collaboration, as well as barriers. Further, STEM Pathways focuses on the important role that ISE learning experiences can play in stimulating students’ engagement, motivation, and confidence in STEM—all of which are important precursors for learning.

The STEM Pathways collaborative model allows for a stronger and more effective relationship among organizations and participating schools and districts. District leaders are more invested advocates, allowing for better alignment with district priorities and support for classroom teachers. The STEM Pathways collaboration has laid the groundwork and established strong relationships that we believe will lead to a large-scale, interconnected system of mutually reinforcing informal and formal STEM learning experiences in our community, as well as a model that could inform other communities striving for similar goals.

An unanticipated discovery is the impact that participation in STEM Pathways has on the professional growth of ISE instructors, the programs they develop and deliver, and the ways in which they view the work they do in a broader community context. “I can’t help but appreciate the unintended professional growth that came out of this experience,” reflected Bekki Rezabek, The Bakken Museum’s K–12 program manager. “Each of the participating organizations previously operated in isolation and, yes, sometimes in direct competition. By coming together, we learned about the similarities, the differences, and the unique features of our programs. There were so many moments of ‘I like how you do that. I want to do that too.’ I came away feeling less like a competitor and more like a team member with a newly expanded support system.”

Classroom teachers have not had the opportunity to consistently participate in these collaborative professional development opportunities, although STEM Pathways partners and MPS see this as an important next step. Therefore, we are offering broader scheduling options and seeking funding for teacher stipends in the next phase of the program. We plan to start in early 2016 with an opportunity for ISE educators and classroom teachers to learn together. This workshop will focus on recently conducted research on students’ dispositions toward STEM, the relationship of these attitudes to learning and motivation, and instructional strategies to strengthen them.

The STEM Pathways partners anticipate that the program model will advance knowledge in several areas important to the STEM education field, including effective strategies (e.g., connecting and sequencing formal and informal STEM education experiences, cross-sector collaboration) for achieving desired student outcomes shared by a community. The project also has the potential to improve STEM instructional capacity through professional development of ISE providers and school teachers, expand and improve access and services to underrepresented students, and promote information sharing between formal education and ISE providers.

By the time this article is published, STEM Pathways partners will be deep into a strategic-planning process to define the future directions and goals of the collaboration. At the same time, to inform this process, research and evaluation of the three-year pilot will provide an understanding of the collaboration’s impact on student outcomes and conditions that support successful implementation and those that create barriers. These processes will define the next phase of STEM Pathways and strategies for sustainability and growth. Check out the Supplementary Resources tab at the beginning of the article for helpful websites, fourth- and fifth-grade portfolios, and teacher guide.

Acknowledgments

This project is made possible by the passion, support, and cooperation of the partnering ISE organizations, the Minnesota Department of Education, the MPS district, and participating schools. Financial contributions from the Boston Scientific Foundation, Department of Defense STARBASE, and STARBASE Minnesota provide funding for research, evaluation, and project coordination. Special thanks to the other contributors to this article: Santi Bromley, Bekki Rezabek, Shoghig Berberian, Elizabeth Stretch, and Kit Wilhite.

Abby Moore (abby.moore@state.mn.us) is School and Teacher Programs Supervisor at the Minnesota Zoo. Beth Murphy (bethmurphyconsulting@gmail.com) an independent STEM education consultant with expertise in forging collaborations between organizations and schools, providing professional learning experiences for educators, and program evaluation that supports practitioners to do their best work. Melanie Peters (mpeters@starbasemn.org) is Program Manager at STARBASE Minnesota. Steven Walvig (walvig@thebakken.org) is Director of Education at The Bakken Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Is Lesson Plan STEM Informal Education