Feature

Collaboration + Good Coffee = Connected Science Learning Success

State Agencies Partner to Unite Formal and Informal Educators in North Carolina

Connected Science Learning May-July 2017 (Volume 1, Issue 3)

By Debra T. Hall, Benita B. Tipton, Lisa Tolley, and Marty Wiggins

A collaboration between two North Carolina state agencies allows in-school and out-of-school educators to share knowledge, engage students in in-school and out-of-school opportunities, and develop learning communities to advance science education in the state.

The K–12 Science Section of the Division of K–12 Curriculum and Instruction in the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) has a long history of working with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs. Both NCDPI and the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs knew the state’s formal and informal science education communities were dedicated to increasing knowledge, awareness, and participation in science for all students, but there were often breakdowns in communication between teachers and informal educators, as well as confusion over state and local school standards and policies. And to many informal educators, both NCDPI and the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs represented somewhat of a mysterious, faceless bureaucracy.

So, in 2011, NCDPI and the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs embarked on a simple, yet effective, model to build integral connections between formal and informal educators to support student learning. Each December, the two agencies host a daylong NCDPI/informal meeting that allows educators from environmental education centers and science museums, as well as other informal science education providers, to meet directly with NCDPI science curriculum specialists and, recently, a panel of classroom teachers.

Meeting to Collaborate

The annual meeting provides an opportunity for informal educators to get updates on state standards. It also shows these educators how to access support documents and resources to help them align their educational programs and field trips with the state’s Essential Standards for Science. Meeting attendance has steadily increased over the years, with more than 100 attending the most recent session in December 2016. The meeting is publicized through the state’s environmental education listserv, which has more than 3,000 subscribers, and through a listserv of more than 200 North Carolina environmental education centers that provide informal science programs. It is also publicized through the Office of Environmental Education’s social media outlets. Registration is free and open to anyone with an interest in building partnerships between formal and informal educators. For those who cannot attend, meeting minutes, presentations, and other informational resources are distributed by the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs to the state’s large informal science and environmental education networks.

Although the NCDPI December meetings began in 2011, the enthusiasm for the gatherings among informal educators has certainly not waned. The impetus to develop 21st-century learners who are scientifically and environmentally literate has continually increased interest and attendance. “We actually had to raise the capacity for our 2016 meeting,” notes Lisa Tolley, environmental education program manager for the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs. “Luckily, the room was able to hold everyone with a bit of creative table rearranging! Many attendees rarely miss a meeting and are disappointed if they have a conflict on the meeting day—that’s why we provide good follow-up information to all of our informal contacts, whether they attend or not.” Also contributing to the increased interest in the meetings was the passage of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which was serendipitously signed into law on the same day as the 2015 annual meeting. This legislation includes language that supports environmental education and environmental literacy programs. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act also supports hands-on learning and “field-based or service learning” to enhance understanding of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, which will provide additional opportunities for environmental science education programs.

The NCDPI K–12 Science Section uses the meetings as an opportunity to share information about educational terms and language, provide information about NCDPI news and events, and distribute information from teacher surveys regarding the needs of North Carolina’s classroom educators. Maria McDaniel, a former science teacher and current education and program director at A Time for Science Nature and Science Learning Center, recalls, “The first time I attended the informal educators meeting, I looked across the room and thought, ‘What a valuable room full of people!’ The meetings have been very informative for the informal educators by helping them match their offerings to the state curriculum. Teachers should feel large arms of support wrapped around them as a result of this collaboration.”

Testimonials of Success

Stories from classrooms and environmental education centers from across North Carolina reveal that the state’s teachers have indeed felt those “arms of support” from informal educators, and the NCDPI/informal meetings strive to improve these formal/informal interactions and educational support networks. Andrea Auclair, a fourth-grade teacher from Creedmoor Elementary School in Granville County, has taken a number of workshops with informal institutions that participate in the NCDPI/informal meetings, including the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. She gives this example of how museum educators helped her do her job even better: “I will be honest, when I was first moved to fourth grade and read in our social studies textbook about pocosins, I thought that it was really obscure and unnecessary to teach. I grew up in North Carolina, but had never been taught about its special ecosystems, and therefore knew nothing about the longleaf pine forests and how special they are. So the first year, my team did not [teach it]. Then I went to a workshop on the longleaf pine ecosystem sponsored by the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and was out wading in a pocosin. The workshop made me realize what we have right here is as special and fascinating as a rain forest. Wow! It totally changed my teaching of science and social studies.”

Rebecca Weaver, an instructional coach at Durant Road Elementary in Wake County, couldn’t agree more about the instructional support offered by the state’s informal education community: “Students love field trips, but especially field trips where they roam through the forests, catch salamanders in ponds, and analyze tracks along the muddy banks of a river. After seeing the excitement and also how easily focused students were while in outdoor learning settings, I realized that environmental education was possible on our own school campus and helped revitalize an outdoor learning space at our school, which we use frequently for instruction, reading, and reflection.” Weaver’s school has formed a close partnership with Blue Jay Point County Park, whose educators are regular NCDPI/informal meeting participants. The school’s kindergarteners and fifth graders visit the park yearly to conduct investigations that support their science curriculum. “The educators at the park are amazing and their love for what they do shines through,” continues Weaver. “The students pick up on that and we often associate other school activities back to the experiences at Blue Jay County Park throughout the year.” D’Nise Hefner, education program director at Blue Jay County Park, notes that the NCDPI/informal meetings help her and her staff better serve teachers such as Weaver: “The benefit of the NCDPI/informal meeting to me is greater understanding in my never-ending quest to learn ‘the language of teachers’—what teachers need, what they want, and how they get their field trip information. I then cross-check that with what we need, what we are able to provide, and how we are able to provide field trip information.”

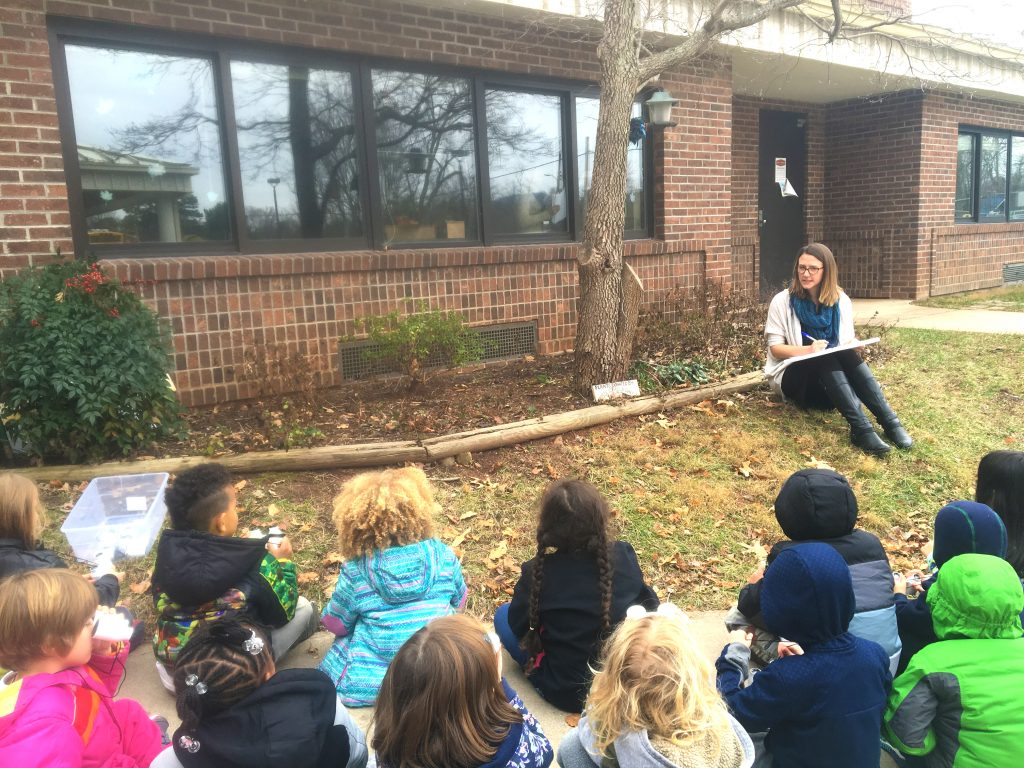

Lindsey Lengyel, a Stormwater SMART environmental programs coordinator with Piedmont Triad Regional Council, collaborates with teachers across five counties on programs that range from in-class activities to multiday environmental field excursions to large-scale stream cleanups via canoe. Lengyel is now implementing changes in her programs for the 2017–2018 academic year based on information she gained from the NCDPI/informal meeting teacher panel, which also inspired her to seek feedback from other teachers she serves. These changes include using real scientific equipment with the classroom students Lengyel interacts with, as teachers noted that in many cases, equipment such as microscopes and water testing supplies are not available to them. Lengyel also notes other changes she plans as a result of information gathered from the meetings, including the creation of educational programming that teachers can use immediately before and after her Stormwater SMART programs to create more cohesive programming. Additionally, she plans to do more in-class or on-campus “field trips,” rather than try to coordinate off-campus field trips—another lesson she learned from NCDPI and teacher presentations at the meetings. “We feel that this will drastically increase our collaboration with formal educators now that we better understand their needs.” These on-campus field trips offer students outdoor opportunities aligned to the North Carolina Essential Standards for Science, providing an alternative when school travel opportunities are limited.

Partnerships even form during the NCDPI/informal meetings. Jonathan Navarro, senior environmental specialist with the North Carolina Division of Air Quality, says their NC Air Awareness Program connected with Sarah P. Duke Gardens, J.C. Raulston Arboretum, the Center for Human–Earth Restoration, and the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission during the NCDPI/informal meeting. “As a result of these meetings, NC Air Awareness completed air quality programs for K–12 students with these new partners. Additionally, as a result of these initial connections, we participate in environmental education summer camp programs with several partners. During these summer camps, we are able to teach kids about air pollution and how they can take steps to be good stewards of the environment,” says Navarro.

Another example of cooperation that brings together classroom teachers and informal educators together that had its origins in the NCDPI/informal meetings is the participation of informal educators at the state’s Regional Education Service Alliance (RESA) professional development meetings. RESAs are held in all eight regions across the state for K–12 science teachers and supervisors. Prior to the NCDPI/informal meetings, out-of-school educators were not represented at the RESA meetings. As a result of discussions during and after the annual NCDPI/informal meetings, informal educators are now invited to attend RESA sessions and connect with participants. The RESA sessions have contributed to capacity building at the local level, as these professional development sessions now set aside time during the meetings so classroom teachers and science supervisors can network with informal educators in their geographic area to discuss curriculum offerings, field trip opportunities, and instructional resources. Miriam Youngquist-Thurow, the environmental education director for the Agape Center for Environmental Education in Fuquay-Varina, has attended several RESA sessions for the regions her center serves. She feels that the opportunity to speak with the teachers in attendance has been the most beneficial result of the sessions. She says, “After sharing what we have to offer, several school teachers have taken part in field trip opportunities [with] their students. Without the RESA opportunities to share what we have to offer, these connections would not have occurred.” The Agape Center serves primarily K–8 students and reaches approximately 5,000 students a year through day and overnight field trips. Youngquist-Thurow adds, “We valued the opportunity to get the word out about what we offer and how we can help teachers reach the goals set forth by NCDPI for essential standards for science and social studies.”

Renee Strnad, an environmental educator and Project Learning Tree state coordinator with North Carolina State University’s Department of Forestry, is another informal educator who has taken advantage of the RESAs and the annual December NCDPI/informal session. This year, Strnad is piloting a blended workshop model using Project Learning Tree with more than 30 elementary science specialists in Wake County. Teachers will complete three hours of asynchronous online training before attending two face-to-face sessions. North Carolina Project Learning Tree provides low-cost or no-cost professional development to preservice teachers across the state. They also provide in-service professional development workshops for schools and school districts throughout North Carolina. Strnad says, “These professional development events allow teachers to gain valuable science content knowledge and receive nationally acclaimed curriculum materials that help promote using the environment as a learning context, place-based and project-based learning opportunities, and critical thinking and literacy skills.” Strnad says that the NCDPI meetings have helped her understand the demands on teachers’ time and the importance of crafting a workshop that fits teachers’ schedule and objectives. “The meetings have also helped me speak the language of teachers so that we all come to a professional development experience with the same expectations.”

Partnering to Enhance Student Experiences

“In North Carolina, we are always looking to support student learning in a variety of ways, and in the process have developed a unique partnership that encourages collaboration between schools, school districts, NCDPI, and the informal education community to support science learning and environmental literacy,” says Debra Hall, elementary science consultant for the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. The Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs’ Lisa Tolley adds that North Carolina “has one of the strongest informal environmental education communities in the country, and our partnership with NCDPI is another way we can further the already diverse and effective environmental science programming available to students, which benefits both the formal and informal education community.”

Indeed, many of the regular meeting attendees have developed amazing collaborative efforts over the last six years, which have benefitted them as informal educators by building regional capacity for their individual organizational and agency educational goals. The meetings have likewise benefited formal classroom teachers by providing authentic science learning opportunities that are correlated to state standards.

The North Carolina Arboretum in Asheville partners with schools across western North Carolina through a citizen science mini-grant program called Project EXPLORE (Experiences Promoting Learning Outdoors for Research and Education). The Arboretum youth educators regularly attend the NCDPI/informal meeting. Trudie Henninger, citizen science coordinator with the arboretum, says the information provided by representatives of NCDPI helped their staff develop the Project EXPLORE program. “The most recent meeting, with the inclusion of a teacher discussion, affirmed our belief that on-site field trips are a necessary means of reaching students through environmental education, eliminating travel time and costs. Project EXPLORE uses a place-based approach to engage students where they’re already learning,” says Henninger. Through the program, the arboretum’s environmental educators model outdoor education techniques for teachers as students are guided through an introduction for three citizen science projects. Henninger says that because they can offer the program freely to teachers and students, they are able to reach students who are not typically served by on-site field trips. Over the past four years, the arboretum has partnered with 96 teachers in 52 schools and served 5,094 students in 21 counties. Mary Hannah Cline, a teacher at Green Hope Elementary School in Wake County, is one of the Project EXPLORE participants. Her class is doing a tree phenology citizen science project and has a dedicated class tree that they visit each week to note seasonal changes and other observations, which students record in their science journals and on the Nature’s Notebook’s data platform. Nature’s Notebook is a national, online program where amateur and professional naturalists regularly record observations of plants and animals to generate long-term data sets used for scientific discovery and decision-making. Cline says, “A facilitator from the arboretum will visit our class two to three times this year. [It] is always incredibly exciting for the students to have a ‘real scientist’ come to our class! I think this project has expanded my students’ understanding of what science is and what a scientist looks like. It is also a valuable experience for them to understand that they have an impact on the scientific community, even as kindergartners, by ‘telling the scientists’ our findings about the tree’s changes.”

Henninger says teachers report an increased interest in science from their students, often noting interest from students who are usually unmotivated by traditional classroom activities. She says, “We partner with remarkable teachers [who] are excited to learn new ways to meet the required standards, enriched by outdoor experiences. In an increasingly indoor culture, it is not uncommon that they will be one of the only persons that these students will regularly go outside with—all in the name of science!”

Along our state’s coastline, the North Carolina Coastal Reserve offers a program called Seeds to Shoreline, which pairs the agency with area schools. Lori Davis, education coordinator with the Coastal Reserve, credits the NCDPI/informal meetings with keeping her up to date on the latest changes and nuances of the state curriculum standards, which are essential to the success of Seeds to Shoreline and the Reserve’s other school programs. Seeds to Shoreline is designed to have teachers and students grow Spartina alterniflora, or saltmarsh cordgrass, seeds in their classrooms, and gives students hands-on, outdoor science experiences that are correlated to state science objectives. The adult saltmarsh cordgrass plants are planted on North Carolina Coastal Reserve properties, enhancing coastal ecosystems and allowing students to take part in real coastal conservation efforts. “This is a wonderful partnership with local schools because it allows the teachers to have a multi-month project focusing on the importance of this plant to North Carolina’s estuaries, the plant growing process, and being an environmental steward,” says Davis. The Coastal Reserve also facilitates school field trips to the Rachel Carson Reserve for two-hour nature hikes focused on estuaries. The field trips are developed for and tailored to each group’s grade level and to the state science standards. Davis says that the NCDPI/informal meetings and the interactions she has there keep her informed of new ways to plan field trips and write curriculum materials so they meet state standards. “I always come away with something new. Since our activities are aligned with the state standards, it helps to meet with NCDPI and my informal colleagues to discuss what standards we should be focusing on and chat with them about new activities we have in mind.” The Coastal Reserve also provides professional development experiences for teachers. Coastal Explorations is a six-hour workshop focused on estuaries and coastal ecology. Teachers on the Estuary is a multiday workshop that goes into depth on coastal ecology and allows teachers to spend more time with researchers conducting stewardship and research projects at one of the reserve sites.

Photo credit: E. Woodward/N.C. Coastal Reserve

Photo credit: David Sybert, K–12 education specialist, UNC Coastal Studies Institute

Partnership Benefits for Classroom Teachers

These collaborations also include informal educators providing professional development for preservice teachers. Tanya Poole, southern mountain education specialist and state Project WILD coordinator with the Wildlife Resources Commission, provides training to preservice teachers in addition to her professional development for inservice teachers. She says, “All elementary education majors at Appalachian State University are required to be trained in Project WILD, and a larger portion of them are training through multiple workshops. It ends up being around 200–250 preservice teachers a year who will go into their classrooms with at least one, if not multiple, environmental education curricula to support their teaching.” Poole feels that the meetings with NCDPI have been beneficial for connecting with the formal community. “Through these meetings, I have learned new language to help me connect with teachers and principals. I am also updated on new trends and programs that are important to NCDPI, principals, and classroom teachers. This allows me to adjust my programming as needed to meet their needs. It also helps me train other informal educators on how to connect better with classroom teachers,” says Poole. She feels that the relationships she has built with staff from NCDPI have helped her in developing programs or materials for formal and informal educators. She adds, “As a result [of this relationship], we put energy into a product we know classroom teachers need and will likely use, as opposed to guessing what teachers need, putting the work into a project, and then realizing it just doesn’t fit with what teachers really need.”

And the good coffee mentioned in the title of this article? North Carolina is a geographically elongated state—more than 500 miles east to west—so many of the attendees have to get up quite early to travel to the meeting. “They always make sure we have plenty of good coffee, tea, and baked goods at the start of the meeting, and it seems to get us off to a good start,” notes Cindy Lincoln, coordinator of the Naturalist Center at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Two nonprofits that represent informal educators in the state, the Environmental Educators of North Carolina (EENC) and the North Carolina Association of Environmental Education Centers (NCAEEC), have partnered to sponsor the coffee breaks at the annual meeting. Even more important than the coffee, both EENC and NCAEEC are essential partners in ensuring the state has quality informal educators by providing ongoing professional development opportunities. They also encourage their respective memberships to partner with both NCDPI and their local teachers and school districts.

EENC and NCAEEC also work closely with the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs. As the state’s clearinghouse for environmental education, the Office makes sure that teachers have access to the wide array of professional development trainings offered by informal educators and facilities throughout the state. “All the coastal ecology that I know, I learned by going out into the coastal environment with informal educators and getting dirty,” says Phillip Cox, a science teacher at Northwood High School in Chatham County. “This allows me to bring a rich experience into the classroom when I can’t take the students to the coast. The students also appreciated the richness that I bring to the class instruction. They don’t have to learn about something from a book or online when they can actually see the creature or sand from the coast. They can do an activity or lab to simulate what they might do at the coast.” Cox has led activities involving looking at sand under a microscope and studying the stream on the school’s campus. “Professional development with informal educators allows classroom teachers the opportunity to learn about the topic and feel comfortable modeling this for the students and integrating it into the curriculum. For example, not too many teachers would go out and collect leaf litter with the students to set up a Berlese funnel and collect leaf litter organisms for a lab on populations and soil quality on their own. However, if [classroom teachers] go out and learn about this with an informal educator, they will feel comfortable enough to do it in their classroom, which also amazes the students.”

For six years, coffee, colleagues, and a spirit of collaboration have united formal and informal science educators in North Carolina to share a purpose and vision for science education in the state. NCDPI, the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs, EENC, and NCAEEC plan to make this beneficial collaboration continue to grow and develop as outstanding formal and informal educators work toward improving science education for K–12 students. If you are interested in developing a similar meeting in your state, staff from NCDPI and the Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs will be glad to share with you. Contact the N.C. Department of Public Instruction Science Section or the N.C. Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs.

Debra T. Hall (Debra.Hall@dpi.nc.gov) is an elementary science consultant at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction in Raleigh, North Carolina. Benita B. Tipton (Benita.tipton@dpi.nc.gov) is a secondary science consultant at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction in Raleigh, North Carolina. Lisa Tolley (lisa.tolley@ncdenr.gov) is an environmental education program manager at the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality in Raleigh, North Carolina. Marty Wiggins (marty.wiggins@ncdenr.gov) is an environmental education program consultant at the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality in Raleigh, North Carolina.