Two-Year Community

Applying the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) Framework During a Community College Chemistry Project-Based Learning Activity

Journal of College Science Teaching—November/December 2020 (Volume 50, Issue 2)

By Patricia G. Patrick, William Bryan, and Shirley M. Matteson

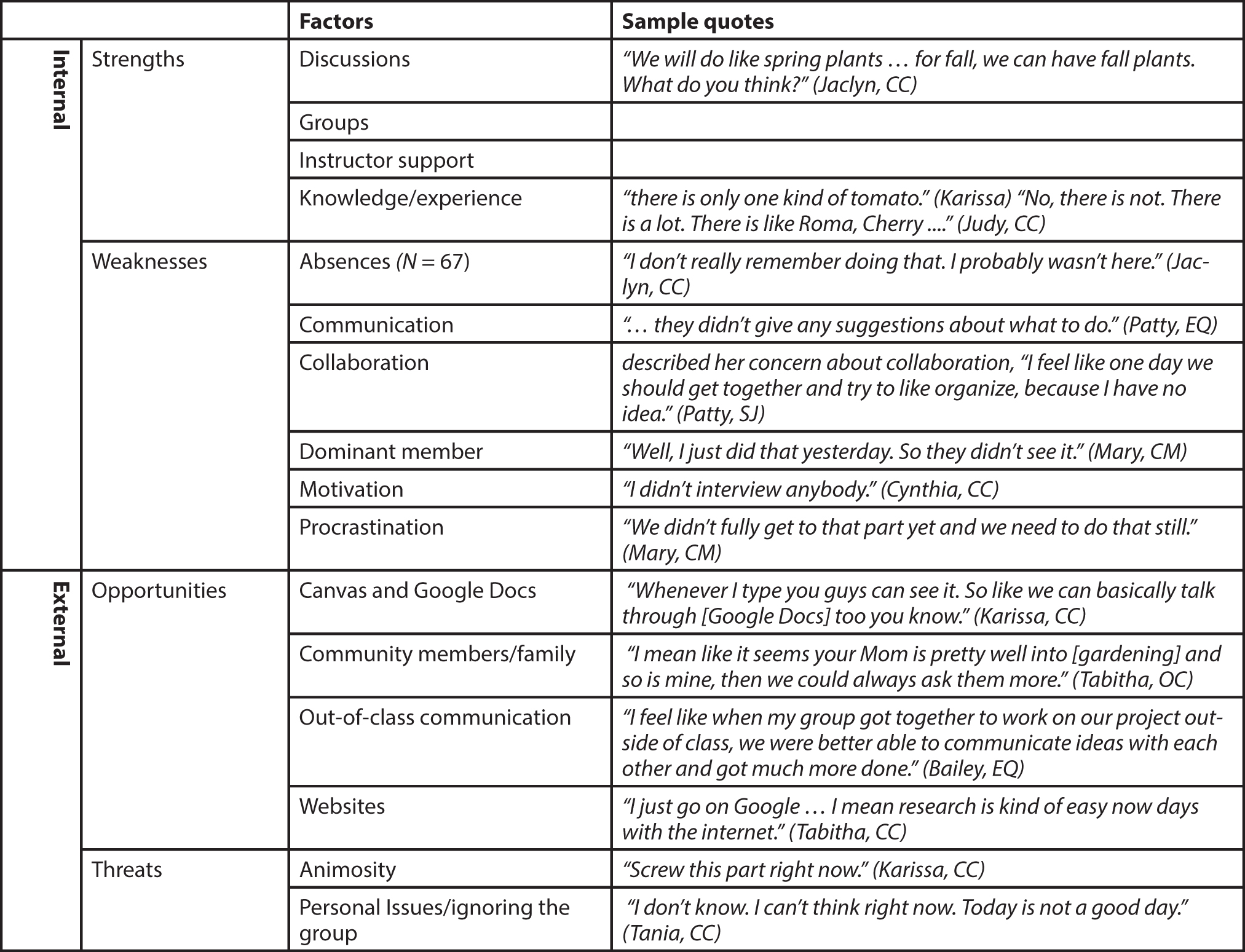

Project-based learning (PBL) instructional methods attempt to make connections between students and their ability to solve real problems. We framed our qualitative study within sociocultural theory and used the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) model to define the positive and negative factors occurring during a PBL activity. We followed 22 rural community college chemistry students during a garden-based PBL activity and collected data through discussions, observations, open-ended exam questions, semi-structured interviews, and reflective journals. Our goal was to identify the social influences on groups in real time, meaning defining group interactions as they were occurring, and organize the findings within a SWOT framework. We discovered four strengths (discussions, groups, instructor support, and knowledge/experience), six weaknesses (absences, collaboration, communication, dominant member, motivation, and procrastination), four opportunities (Canvas and Google Docs, community members/family, out-of -class communication/discussions, and websites), and two threats (animosity and personal issues/ignoring the group). The results offer insight into the complex network of social interactions within the peer group. We include strategies for finding the right balance between SWOT factors.

Project-based learning (PBL) instructional methods attempt to make connections between students and their ability to solve real problems. PBL activities engage students in the use of various scientific practices including planning and carrying out investigations, developing and using models, and justifying a position with evidence (Krajcik, 2015). Placing students in heterogeneous PBL groups encourages social interactions and increases their access to intellectual capital (e.g., Sulasih et al., 2018). Even though the premise of PBL is group interactions, the internal and external factors influencing the group are seldom studied (e.g., Skinner et al., 2015).

We were interested in how peer-learning groups in a community college chemistry course interacted. Understanding the interactions of peer-learning groups and the factors that influence the group are important as educators plan group projects. Moreover, appreciating how external and internal factors influence the peer group is critical in a student-driven instructional approach. Peer-group learning occurs when group members collaborate by working together and sharing their experiences (Kemmis et al., 2014; Pennanen et al., 2020).

Our results augment the literature on freshman Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) courses and instructional methods at two-year community colleges (students ages 18+ years) and Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) literature by expanding the model to define the interactions within PBL groups. The findings add to the PBL literature because we identify factors influencing group learning and provide suggestions for how professors may use SWOT as an evaluative tool during PBL.

Theoretical framework

Sociocultural learning theory states that people learn during social interactions (Rogoff, 2003). PBL groups and interactions are socially constructed and socially mediated. Based on the theory, members of the peer group should build knowledge through active engagement and by sharing experiences (Wenger, 2009; Miller, 2011). As the peer group interacts, there should be a connection between the PBL activity, group social interactions, and experiences. The social interactions occurring in the group are determined by internal and external factors. To define the internal and external factors occurring, while students completed a garden-based PBL activity we used the SWOT schema. Our goal for data collection was to identify the influences of the factors on groups in real time, meaning defining group interactions as they were occurring and organizing the findings within a SWOT framework.

Methodology

This qualitative study followed an interpretive case study (Yin, 2014) using SWOT. Organizations use SWOT to define their internal strengths and weaknesses and external threats and opportunities (Bartol & Martin, 1991). Prior to this study, SWOT was employed in a few PBL studies (e.g., Lima et al., 2017), but researchers did not apply it as a method to analyze the external and internal factors influencing PBL groups. We redefined the items in SWOT to fit our study based on the definitions by Romero-Gutierrez et al. (2016): Internal: Factors occurring in the classroom. Strengths: Positive comments about the PBL group and activities, instructor activities/support Weaknesses: Absences, negative comments about the PBL group, unsuccessful activities External: Factors occurring outside the classroom. Opportunities: Provided by the instructor, but used outside the classroom or mentioned by students Threats: Occurred outside the classroom or brought to the classroom

Participants

The participants for this study were 22 nonSTEM major, freshman-level community college students enrolled in two chemistry classes. The 22 students were 17 females, 5 males, 5 freshman, 16 sophomores, 1 nontraditional student (25 years of age or older), 1 Asian, 1 African American, 9 Caucasians, 11 Latinos, and 11 athletes. Students were divided into eight groups of two to four students.

The rural community college (ages 18 years or older) was located in the Midwest United States. The course instructor, who is the second author, taught at the institution for 18 years. The chemistry course included a 12-week garden-focused PBL activity. The course met seven hours a week—one hour Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and two hours on Tuesday and Thursday. The PBL included predetermined garden-related, in-class discussions and reflective journal prompts, weekly assignments, and lectures.

PBL activity

The chemistry course involved a 16-week PBL garden activity and included the following directions: As a representative of ACME chemical solutions, you are to develop a proposal for the community of Harmony. Harmony would like to be an environmentally friendly and self-sustainable community. You should design a community garden, which involves composting and reusing materials, while meeting the needs of the community. The garden should have a variety of plants to provide for the community members. There are two potential locations: the rooftops of two adjacent apartment complexes or an empty lot. You will produce a presentation and 15-page report for the community members detailing the chemistry involved in various aspects of your planned solution. The report must include a minimum of 40 types or varieties of plants, chemistry of composting and soil incorporation, chemistry of soil manipulation (e.g. pH, nitrogen, magnesium, iron, etc.), and a section on plant chemistry (e.g., nutrients, aromatics).

Data collection

Based on the SWOT model, we captured data from (1) two audio-recorded, group-instructor consultation meetings for each group (CM) and 10 class conversations (CC), (2) audio-recorded group work from one group occurring outside of class (OC), (3) a researcher observation notebook of students during class group work, which recorded seating positions, nonverbal communication, participation, attendance, contributions to group work, and PBL activity decisions (ON), (4) weekly student journals reflecting on the past week, including elements of the scientific process, materials, procedures, and results and experiences and knowledge gained (SJ), (5) semi-structured interviews of four student volunteers, after the course ended (SI), (6) open-ended exam questions, which asked about knowledge of gardens and weekly discussions and work completed (EQ). The acronyms above are included within the results section to indicate triangulation of data.

Data analysis

We completed a deductive constant comparative analysis of the data with the terms strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats as a priori themes, which meant that codes were identified and placed within one of the themes (Saldaña, 2015). We began by reading and rereading the data to determine codes for each theme. When new codes stopped emerging, rules of inclusion were developed. We used the codes to analyze the data and track the groups referring to each theme, resulting in the data that are presented in Table 1 with sample quotations (names are pseudonyms) for each code.

Results

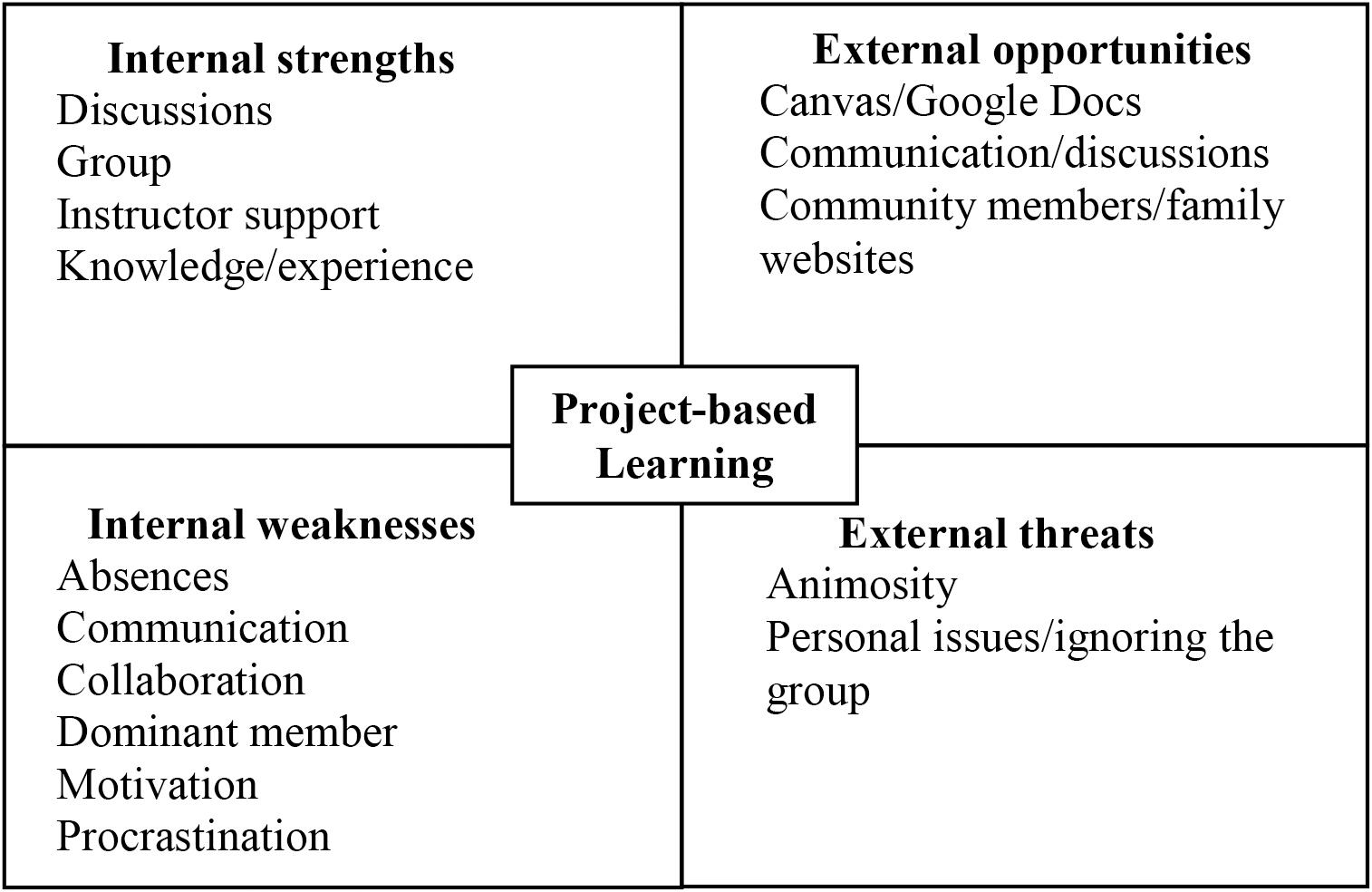

Figure 1 shows the SWOT themes and the codes for the themes. In this study, we call the codes “factors.” While data were collected from eight groups, the results were similar, meaning the SWOT themes occurred in all groups; therefore, we report the data as an overall view of the findings, not as numbers of groups for each theme. We discovered four strengths, six weaknesses, four opportunities, and two threats. Table 1 presents the themes, codes, and sample quotes (when appropriate).

SWOT for project-based learning.

Internal strengths

Discussions. As part of the PBL, the professor included in-class discussions. The discussions were meant to encourage collaboration and idea sharing. Discussions allowed groups to create and describe elements of their garden design. A student (Dallas) described the importance of composting and using a three-row cycle, which influenced the final layout of their garden (EQ).

Groups. Students participated in one of eight groups based on their involvement in athletics and completion of a mathematics course. Athletes were divided across the eight groups, meaning all groups had at least one athlete, so the project could move forward even if the athletes were absent. The groups consisted of athletes and nonathletes and were gender and racially diverse, which allowed for a breadth of prior experiences (ON).

Instructor support. During classroom instruction, the instructor discussed the chemical processes of corrosion, decomposition, lighting sources, rainfall collection, and soil chemistry. Students conducted experiments on soil additives and environmental pollution. During group discussions, the professor interacted with groups and listened (ON).

Knowledge/experience. Peer group members shared knowledge gained from research outside of class, personal gardening knowledge, and experiences they had with family members. Bailey (OC) brought up plant varieties from her research noting “The beets … pair with bush beans only.” Additionally, students mentioned personal experiences. Tania (CC) shared her employment experiences, “I work at this place … they bring [produce] to like a packing house.” The knowledge and personal experiences peers shared with the group drove group interactions. For example, when sharing knowledge, group members debated with each other if the knowledge was correct (CC). In some instances, the results from the conversations and debates were added to the final project.

Internal weaknesses

Absences. During the 10 discussion days and two consultations days (meeting with each group), the students accrued 67 absences. Additionally, absences occurred on instructional and investigation days (ON). Even though placing athletes across groups instead of in a group of athletes was intended to be a strength, athletes used absences as an excuse for not completing work. Absences were an issue for nonathletes too. Karissa stated (CC), “I am never here so I don’t know what is going on half the time.”

Absences led to students not having the information needed for group discussions.

Blanche (CM) stated, “Tania has all that.” However, Tania was absent the day of the consultation. Additionally, absences triggered negative feelings toward group members. Jacob recorded in his journal, “It becomes frustrating when there was only two people in our group who were putting in time to create our paper.” Absences were a main internal weakness and led to many of the internal weaknesses described below.

Communication. Low class attendance led to a lack of communication. For example, Cynthia (SI), who had the most absences, reflected, “Something that was huge in my group was lack of communication.” However, being absent was not the issue for other’s lack of communication. Groups had members that did not talk during group meetings. Alexia (CC) would be present for the conversations, but would not talk during the discussions. Group members ignored each other, which resulted in a lack of collaboration.

Collaboration. Lack of communication led to trouble collaborating. Students did not work collaboratively; instead, they assigned work to members of the group, which is cooperative work. Kate (SJ) described the cooperative approach in her reflective journal writing, “My team and I have all been working on our individual research. Each one of us has our own section to gather information on.” Assigning work to individual members became an issue for the groups when work was not completed.

Dominant member. The lack of collaboration and/or cooperation brought about a dominant group leader. In five of the groups, a dominant member led the meetings and completed most of the work (ON, CC, SI, EQ). Mary’s group provided the best example. Even though Mary ignored her group and did not participate with them in group discussions, she was the dominant person (ON). Mary submitted a completed garden layout, which her group did not approve (EQ). When asked to show the garden to her group, she ignored the group and said to the instructor (CC), “This is what we are going to do.” The group responded by saying, “…me [Kate] and Ariel would…put our ideas to what she had put…But she would change it.”

Motivation. Student groups exhibited a lack of motivation (ON). Even though in-class discussions were meant to encourage sharing of ideas, the groups did not discuss the topics. Students did not complete homework assignments. Students skipped discussion prompts that related to the homework. Tania declared (CC), “I haven’t read the requirements.”

Apathy during the PBL manifested as students looked for shortcuts and the easiest way to complete the project. Suzanne (OC) told her partners “I am trying to do not a lot, you know what I mean?” Tania (CC) asked the group to include, “like simple things that don’t require too much work and don’t take too long to grow.”

Procrastination. Despite seeing each other daily and a final deadline, students noted a need to begin working on the project. Cynthia (CC) stated “We need to step our game up. We have been slacking a lot.” Many of the groups waited until a couple of weeks before the due date to compile major parts of the proposal (ON). Cortez (SJ, SI) noted his group procrastinated and began working on the project two weeks before the due date.

External opportunities

Canvas and Google Docs. In Canvas (online course platform), the professor embedded two weekly discussions about plant needs and the sources for essential nutrients and a Google Doc, where students were meant to write the final paper. In Google Docs, the instructor could view student progress, see who posted and what they posted, and identify comments or questions students posed to the group. Students recognized Google Doc as a method for asynchronous communication (ON). Even though the instructor intended for Canvas and Google Docs to be an external aid, some students placed their work in a separate Google Doc the professor could not access (ON). By not allowing the professor to access the Google Doc, the Doc became an external threat for some groups.

Community members/family. The professor asked students to collect data from the community about gardens/gardening and the need for a community garden. The professor saw this as a positive external source of information and suggested students contact or visit garden centers, acquaintances that gardened, the sustainable agriculture instructor, and so on. However, Manuel (CC) was the only student to suggest, “We should go to the agriculture building, to ask them questions like, ‘what grows here?’” Additionally, students mentioned friends and family as a source of gardening knowledge (CC, OC, SJ, SI, EQ).

Out-of-class communication. Students mentioned meeting face-to-face outside of class or out-of-class communication methods (CC, SI, SJ, EQ). Students found meeting outside of class difficult, but groups who met described the meetings as useful (SI, SJ). Additionally, students described their interactions using Facebook. Patty stated (SI), “we had like a Facebook group that we messaged on a lot.”

Websites. Students mentioned plant websites (CC, OC, SJ, SI, EQ). Students specifically identified Google as the search engine used to find information. Tania (CM) thought the internet as a source of information was superior to asking people about their lived experiences, “I mean you could ask other people, but I feel like Google is honestly just the ideal and the easiest.” Groups described specific internet searches. Bailey (CM) noted she “would Google natural household or natural additives for gardens.” Even though students used a search engine, they reported collecting data from one website. Mary (CM) noted “I only looked at one. Because it had so much, I was like okay I am just going to look at this one.”

External threats

Animosity. Over the 12 weeks, students displayed anger about the project. Bailey’s (CC) comments are an example of the anger: “Ace could probably give us a freaking layout. That is what they do…I am just going to &*&*ing do that, because they have to know something.” Team members (CM, CC) were angry about the amount of work associated with the PBL and felt the assignments were “way too much work” (Karissa, CC). The anger expressed by some members led to negative experiences for group members and may have attributed to their lack of completing the PBL.

Personal issues/ignoring the group. Students’ personal lives played a negative role in their work with the group. Cynthia (CC) stated “I am so tired.” Additionally, group members ignored other members in the group (CM). Tabitha (SJ) described that her group tried to meet over the semester, but “there was always that person that wouldn’t answer.”

Student suggestions for future project-based learning

Students (n = 4), in the postcourse interview provided suggestions for future students. Students expressed the importance of communication, group collaboration, and completion of work on time. Blanche explained the work requires, “a lot of communication and commitment. Some of the time my team members didn’t have either making it difficult to work on this project.” Karissa expressed, “When having a project this big, it takes a lot of communication…to see what we need and where we stand.”

After the project, students realized the importance of group collaboration. Karissa explained, “I learned … how important group work is. You really can’t do anything to finish the project on your own …” Bailey commented, “I learned that everyone needs to be on the same page to accomplish a goal together.”

The interviewees thought time was an important consideration for future groups. Cynthia mentioned procrastinating as a regret, “I only wish I would’ve tried harder in the beginning …” Blanche reflected similar thoughts: “Don’t slack off…” Karissa described communication and completing work on time as occurring parallel. She suggested, “Communicate with your partner. Don’t wait on them to take the initiative of the project … If there is a deadline, do it. Don’t think you are going to have time to do it at the end of the semester …”

Discussion

Through the SWOT analysis, we identified an array of internal and external factors supporting (n = 8) and undermining (n = 8) the success of the garden PBL. Even though groups had some positive interactions, we found the negative social interactions were influencing the ability of the groups to be successful. SWOT allows a researcher and practitioner to view external and internal factors simultaneously and prioritize factors prone to promote failure and factors expected to aid students in being successful. To address issues, practitioners may emphasize positive factors and identify negative factors to create a feedback loop. The feedback loop is crucial to ensuring the practitioner is aware of threats and weaknesses, which may be overlooked. Understanding SWOT to determine student needs and interactions during a PBL can provide the basis for the feedback loop. Rauch (2007) states researchers should analyze the SWOT data to determine the relationships between the factors. Below, we use Rauch’s questions and approaches to defining the relationships between factors we identified using SWOT.

Relating strengths and opportunities

Internal strengths and opportunities influence each other and are factors that may support the group (Rauch, 2007). The instructor developed the groups based on student athletics. This strength meant someone would always be present for in-class discussions. In this study, discussions took place in the classroom, but seldom took place outside the classroom. During the in-class discussions, students shared their knowledge and experiences with community members, family, and websites. Instructors should leverage the knowledge/experience gained from outside resources to support in-class discussions and student presentations. Students may present to other groups what they know about the topic. Presenting to other groups might foster conversations inside and outside the classroom and an exchange of ideas. The instructor must encourage positive social interactions by asking students to share personal experiences, vignettes, and stories.

Relating strengths to weaknesses and threats

Identifying the relationship between strengths and weaknesses and threats affords the recognition of threats or the development of strengths (Rauch, 2007). Even though the instructor placed students into diverse groups, a dominant individual took over discussions and influenced the project in five of the groups. Dominant members limited the discussion that took place and hindered collaboration.

The instructor provided in-class opportunities to discuss the PBL; however, the groups did not communicate well or work collaboratively. Students did not share ideas by communicating during the class and ignored suggestions made by group members. A lack of communication led to less collaboration, which is an essential component for successful PBL (Krajcik, 2015). The group members shared information based on the assignments, but did not discuss additional information or components to enhance their garden proposal. Instead, students divided the assignment into sections and assigned them to group members.

Relating opportunities and weaknesses

Instructors should use opportunities to minimize weaknesses (Rauch, 2007). The instructor provided a Google Doc, which he intended as a tool of accountability and as a place for the group to collaborate. Additionally, assignments were available on Canvas and discussed in class. However, students did not complete homework assignments. The instructor provided support through Canvas and Google Docs, but students used social media. The instructor requested that groups meet outside of class time, but only one group recorded a meeting outside of class. The lack of meeting online and out of class led to a lack of communication, collaboration, and motivation, which influenced students’ ability to complete homework assignments. The instructor should exploit students’ desire to use social media by including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat.

Opportunities outside the classroom included student interactions with community members, family, and websites. However, students seldom included the information they gleaned from others outside the classroom in the PBL project. Instead, they relied on information from websites. The instructor could invite community members to speak and ask students to apply the information to the PBL.

Relating weaknesses to threats

By reducing internal weakness(es), instructors may avoid external threats (Rauch, 2007). Absences were the greatest contributing factor to the lack of communication, along with an overall lack of motivation to work on the project. Attendance of all group members occurred only during the first in-class discussion session. This led to groups falling behind on deadlines and not completing the project completely. When students attended class, many showed animosity toward other students and the instructor. Some students talked about personal issues as being a reason for not completing the work. Students ignored deadlines, which were essential for completing the next component of the project. During in-class discussions, students ignored others in the group. As a result, group members did not engage with the in-class resources and potential out-of-class resources (e.g., Canvas, community members, family members, gardeners, Google Docs). To minimize weaknesses and threats, instructors should develop checkpoints throughout the PBL. The instructor did meet with students to determine how they were advancing. During the meetings, instructors should provide checkpoints to define group issues and suggestions for how to collaborate and include community members in the discussion. When the instructor identifies group members who are not working well together, the instructor should determine ways to build teamwork or consider moving group members. Additionally, timelines with due dates should include objectives and diagrams showing how an assignment relates to the next assignment. Scaffolding the assignments and providing reasons may develop intrinsic motivation and mitigate procrastination in completing the project.

Implications

From a sociocultural perspective, our results indicate SWOT factors influence each other, which has implications for PBL and practitioners. The SWOT factors identified relate to the social interactions occurring within the groups. In general, peer-group dialogue and social interactions can be valuable learning opportunities (Rogoff, 2003). For example, when students shared knowledge gained from family, the internet, or gardening experiences. However, we caution that PBL groups can be a stressor for students and may result in negative social interactions. Even though students engaged through discussions and shared knowledge and experiences, their interactions did not produce a successful project.

Because the factors are different and interrelated, practitioners must address positive factors to promote successful social interactions and respond to negative social factors in a way that reflects greater participation in resolving weaknesses and threats. Negative factors can be more difficult to recognize than positive factors; therefore, a practitioner may use a SWOT during PBL to detect and moderate factors. Using Figure 1, practitioners could list the SWOT factors they observe and students mention. Once the practitioner identifies the factors, they can better identify how to reconcile the negative factors and support positive factors.

Practitioner–student level interactions are essential for identifying SWOT factors and achieving best PBL practices. Additionally, professors should take into consideration the social interactions of interracial groups, as research indicates children collaborate in different ways (TERC, 2020). These differences may carry over to the college classroom. The challenge remains to understand the complexity of PBL group work and the ways practitioners are instrumental in aiding students as they develop realistic expectations of completing a PBL.