scope on the skies

Would You Believe?

Science Scope—May/June 2023 (Volume 46, Issue 5)

By Bob Riddle

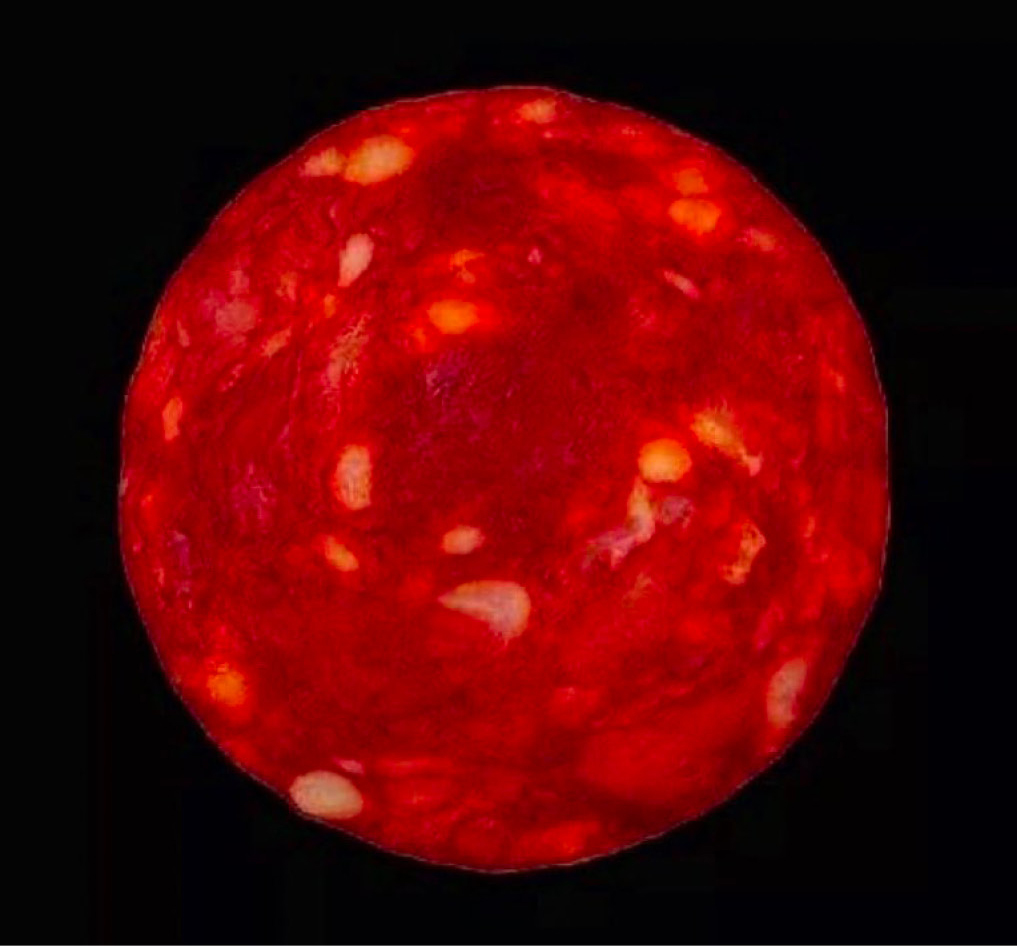

"Would you believe?” was a familiar catchphrase from the 1960’s TV show “Get Smart,” featuring Secret Agent Maxwell Smart. With that phrase in mind, take a close look at Figure 1, a picture that was posted on Twitter and subsequently reposted numerous times (see Online Resources). Would you believe that this is one of those incredible James Webb Space Telescope images, in this case of Proxima Centauri, the closest star outside of our solar system? Considering the many wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum astronomers can use when imaging celestial objects, perhaps this is a picture of that star. How would your students react to the picture?

Twitter-posted picture of Proxima Centauri Star.

In a previous column (“Castles in the Sky,” March/April 2023), the human condition of pareidolia was described as a condition that has us seeing pictures of recognizable objects in cloud shapes, baked goods, or even a sandwich (see Online Resources). So, combine that condition with an audience not that familiar with a subject like astronomy, and the potential for passing something off as real when it is not increases.

But wait! We may look at constellations at night and connect the stars with imaginary dot-to-dot lines to make a recognizable shape with a familiar name—and we may believe these constellations sort of resemble what the name implies. Yet how many of these constellation patterns actually do resemble their names? Short answer: not that many. However, thanks to the book The Stars: A New Way to See Them by H.A. Rey, we can look at constellations and see them as patterns that are a better match for their name. Although the author’s name is familiar to night sky observers, some might also recognize H.A. Rey as the author of the Curious George children’s book series.

When we see the remarkable images taken by the space-based fleet of telescopes, in whatever wavelength of the electromagnetic spectrum has been used, they often have names that may or may not have anything to do with their shape or properties. The name chosen may have had more to do with their awesomeness or to a “wow” reaction to an image. Rather than stick-figure shapes like the constellations, there are celestial objects—like nebula, galaxies, even clusters of stars—that simply remind us of some familiar visual image (see Table 1). Thanks to the images from amateur and professional astronomers and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), the Spitzer, and now the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), we can see the incredible beauty of the universe in a much different and more detailed way.

False color images

Picture taking or digital imaging has come a long way since the time when there were only two colors when taking pictures—black and white! Now most pictures start as digital images and are in color, even natural colors, whereas others have been colorized. Images from observatory and amateur instruments, and from space-based telescopes, are generally received with little or no apparent color. What we see in many of these pictures have been postprocessed to include false colors or to bring out the natural colors by adjusting graphic software settings. False colors are often used to highlight certain features and, when added to an image, are done for aesthetic and scientific reasons. For the latter, colors typically follow the wavelengths being imaged with bluish colors to indicate short wavelengths and reddish colors to indicate longer wavelengths, such as infrared wavelengths.

The image of a celestial object we see when viewing the sky through the eyepiece of an optical instrument, like a telescope, does not look exactly the way a colorful picture of that object might look. Our eyes are not sensitive enough to discern the colors that show up in astrophotography, so we adjust for this by using special filters or telescopes designed for wavelengths other than those within the visible spectrum. Space-based telescopes, such as the HST, JWST, and Spitzer, image objects within certain wavelengths, and with the latter two telescopes, the focus (astronomy pun!) is within the infrared area of the spectrum. The Hubble, primarily a visible light telescope, is capable of imaging into the infrared wavelengths. Since each telescrope sees objects differently, when images from them are combined, the resulting imagery is very striking and very revealing (see Figure 2).

The Phantom Galaxy composite image.

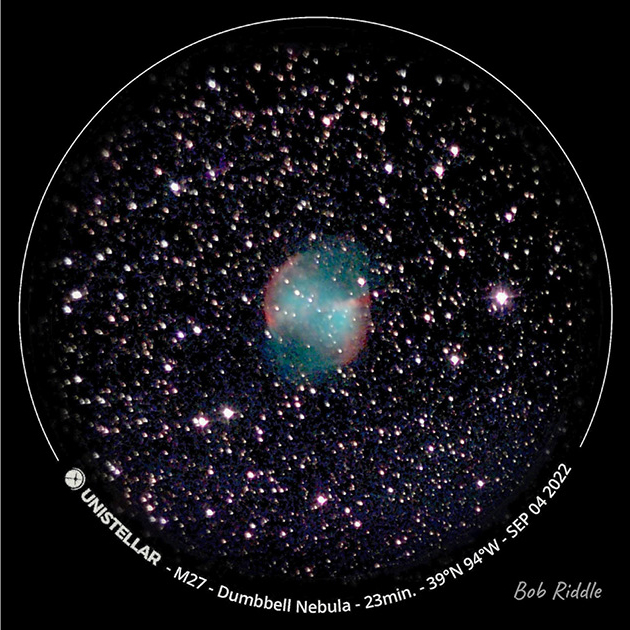

There are, however, images taken in visible light without any filtering that will show some coloring, often depending on the length of the exposure time. The natural colors that sometimes appear in a lengthy visible light exposure picture are mostly blue, red, and green. In a 23-minute time exposure image of the Dumbbell Nebula, bluish colors indicate the presence of oxygen, reddish colors indicate the presence of nitrogen and sulfur, and hydrogen is indicated by a faint greenish color (see Figure 3).

Visible Light Image of M57, the Dumbbell Nebula.

Students may explore imaging celestial objects in either black and white or color by sending their requests to a telescope operated by Observing With NASA (OWN; see link to website Online Resources). Black and white imaging is done by selecting an object with the correct imaging settings. Color images are created by requesting three separate images—first requesting an image of the object with a red, then with a green filter, and then with a blue filter. Students use an online image processing at the OWN website to post-process the three images into a color image. Tutorials and step-by-step directions are available at the OWN website to aid students in their explorations (note: images are e-mailed to the requestor).

Real or visualization?

Our students, like us, are visually oriented, so the use of imagery as a source of information for teaching science is important. Thus, it is also important that the imagery we share or that students come across is understood by them to be valid or not valid and that they know how to determine the validity of a picture. This column started with the picture of Chorizo sausage posted and reposted as the star Proxima Centauri. This is not the only time folks, especially via social media, have been taken in by fake pictures. A search using the phrase “fake astronomy picture,” for example, will return numerous links. Despite the misinformation of fake pictures, they do offer teachable moments and even assessment opportunities. Some of these pictures are great as ice-breakers—for example, students might form “scientific investigative teams” to determine the validity of an image as well as present their findings to their peers.

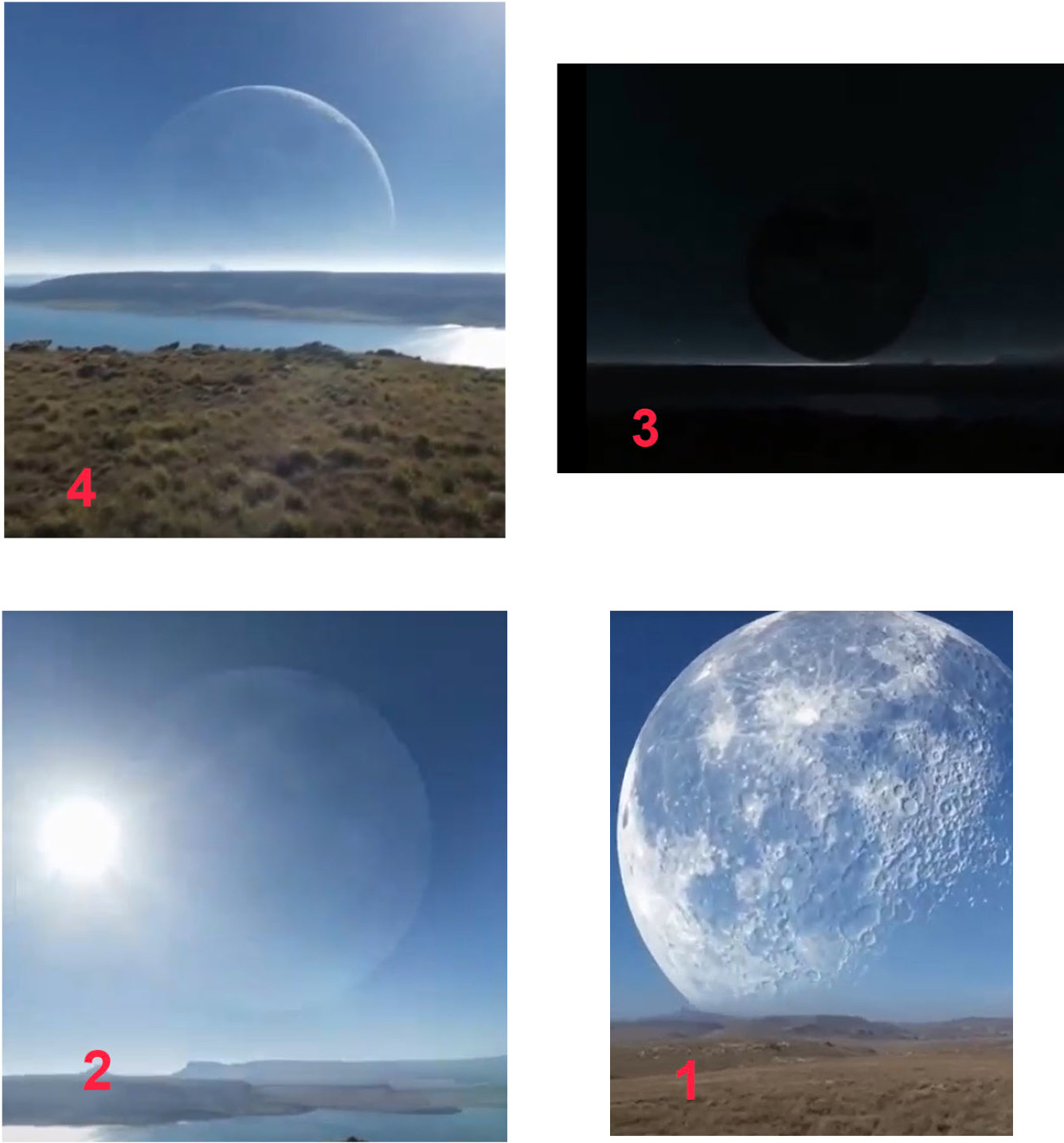

There is a short video that has made its way around the various social media platforms that shows a full and fully illuminated Moon rising above the horizon somewhere along the Arctic Circle. As the Moon rises, the video shows the full Moon moving from right to left and passing in front of the Sun. For a moment there is a total solar eclipse before the Moon reappears on the other side of the Sun and then sets as a crescent phase (see Figure 4). Students who have learned about Moon phases and eclipses—plus have common sense—will realize that this video could not be real. One very obvious reason is that if the Sun is beyond and behind the Moon, as it would be during or near new Moon phase, and there is a total solar eclipse, then how is the surface of the rising Moon facing toward us in this video illuminated? There are more “issues” with the video, but students can work to determine those.

Screen captures from Viral Moon Rising Video.

For students

- Use the Aladin website to request images of celestial objects in different wavelengths. How does an image of an object appear when viewed at different wavelengths?

- Can you find the one correct image from the APOD mosaic (see Online Resources)?

- Request your own images of celestial objects at the Observe With NASA website (see Online Resources).

ONLINE RESOURCES

Aladin Lite—aladin.u-strasbg.fr/AladinLite/

Asteroid Day—asteroidday.org/

Butterfly Nebula—https://go.nasa.gov/3nhf94k

Castles in the Sky—Science Scope, Scope on the Skies. Bob Riddle. March/April 2023.

Dark Shark Nebula—apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap150907.html

Fake pictures mosaic—apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap211109.html

Penumbral lunar eclipse—https://bit.ly/3Z9a1g1

H.A. Rey—en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H.A. Rey

Helix Nebula—https://go.nasa.gov/3JHYjTN

Hubble Space Telescope images—https://go.nasa.gov/3JCq9AO

James Webb Space Telescope and Chorizo—https://bit.ly/3JMrm8G

James Webb Space Telescope images—https://go.nasa.gov/40CQrdb

Manatee Nebula—www.nrao.edu/pr/2013/w50/

National Astronaut Day—https://bit.ly/3nlGUZn

National Space Day—nationaltoday.com/national-space-day/

NASA Visualization Studio—svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/

NASA Visualization Explorer—nasaviz.gsfc.nasa.gov/

Observing With NASA—mo-www.cfa.harvard.edu/OWN/

Owl Nebula—https://bit.ly/3lI8EXV

Phantom Galaxy—https://bit.ly/3JIblRk

Snake Nebula—apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap020409.html

Spitzer Space Telescope images—https://go.nasa.gov/3nigFTT

Star Wars Day—starwars.com/star-wars-day

Tarantula Nebula—https://go.nasa.gov/3K6W4L8

The Stars: A New Way to See Them—https://bit.ly/3K2VKMr

Towel Day—www.towelday.org/

Twitter Post JWST Star Picture—https://twitter.com/nasawebb?lang=en

Viral video of moon rising—https://bit.ly/3TDU5Bj

World Ocean Day—https://bit.ly/3K69mYf

Bob Riddle (bob-riddle@currentsky.com) is a science educator in Lee’s Summit, Missouri. Visit his astronomy website at https://currentsky.com.

Astronomy Earth & Space Science