Scope on the Skies

The Red Issue

At least three space agencies are now on their respective way to the “Red Planet” Mars, following successful completion of the first two of several phases of their mission to Mars. Launched this past July and August, the NASA rover Perseverance, the Arab Emirates orbiter, and the Chinese Space Agency’s orbiter and rover are still six to eight months from orbital insertion at Mars. After the launch into Earth orbit, engines are again fired to send the spacecraft toward where Mars will be when the spacecraft arrives months from now. When interplanetary cruising speed is reached, the engines cut off and are detached from the Mars-bound spacecraft. Then for the next several months, the spacecraft is in the cruise phase of the mission, the time between launch and arrival at Mars. Arrival at Mars sets up basically one of two sequences for the spacecraft. The spacecraft could either enter orbit around Mars beginning an orbiter-based mission, or the spacecraft could prepare for landing on the surface of Mars.

So what happens during the cruise phase? Is the spacecraft shut down? Do the scientists, the engineers, and others involved with the mission take a break while the spacecraft “cruises” toward its rendezvous with Mars?

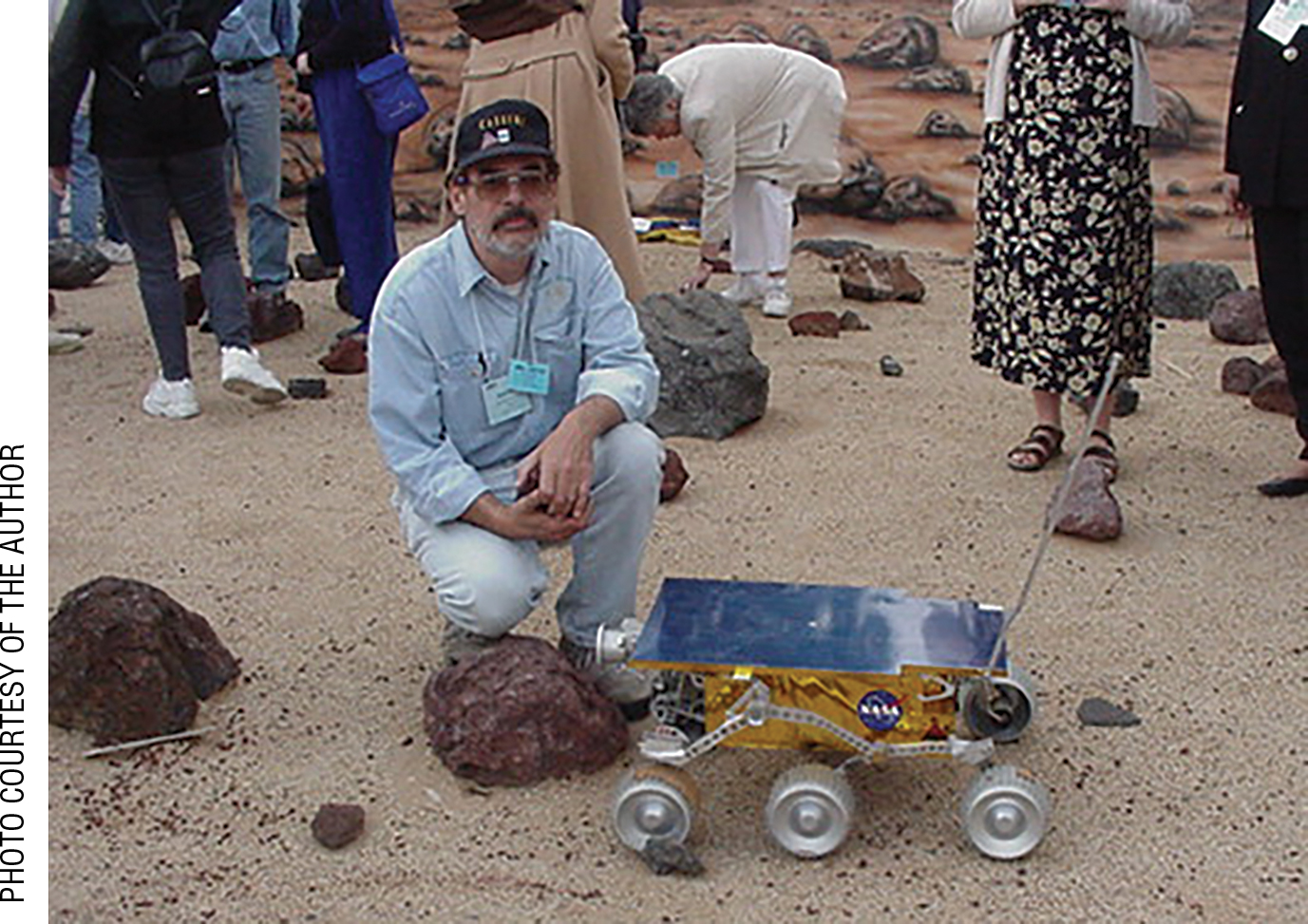

The cruise phase of a mission to Mars lasts about 7 to 9 months during which time mission-involved people work on a variety of tasks in anticipation of the arrival at Mars. For example, they practice sequences for orbital insertion or landing on the surface. Instruments are periodically checked and rechecked, and simulations mimicking spacecraft, lander, or rover operations are run. Think dress rehearsals. If a rover or lander is part of the mission, then a twin of the rover or lander is used at NASA’s In-Situ Lab, or at an outdoor environment similar to the landing site on Mars, to test and practice for the eventual on-the-surface part of the mission (see “Challenges of Getting to Mars” video under Resources; see also Figure 1).

The author in the Mars In-Situ Lab with the Sojourner rover twin

Book your passage to Mars

During the cruise phase of the mission, those involved stay occupied. What do you do to keep occupied over extended time periods? How about our students? So what could students do during the cruise phase besides following along on the mission web site? How about reading a good book?

As science teachers, we are in many ways reading teachers, with the content area being science. All of us have our favorite reading lists for our students, and many include access to E-books downloaded via the Overdrive app (see Resources), online Interactive E-books, and E-books in PDF or other text formats. So what would be some good reads for students in our science classes, and where are science-based E-books available? Obviously, many of what will be described will be space related (go figure!), but all the sites are not limited to only space topics. How to choose is up to you, but there are also many reviews of reading materials in this journal and other NSTA publications to help in making selections (see Figure 2).

Some commercial sources for middle school books about space

|

Sources |

Web address |

|

Brightly |

www.readbrightly.com/girl-centered-middle-grade-science-fiction/ |

|

Scholastic Magazine |

|

|

reThinkELA |

www.rethinkela.com/2014/11/8-science-fiction-short-stories-for-middle-school/ |

|

Astronomy-free textbook |

|

|

We Are Teachers |

openstax.org/details/astronomywww.weareteachers.com/best-short-stories-for-middle-schoolers/ |

|

Goodreads |

www.goodreads.com/list/show/77925.Best_Middle_Grade_Sci_Fi_Space_Opera |

I would suggest going “old school” and having students read Podkayne of Mars or Red Planet, both by Robert Heinlein. These books were among the many books Heinlein wrote with a young person as the main character. In these stories, his vision of conditions on Mars was based on our limited observations of Mars with Earth-based telescopes. He imagined the canals filled with ice and used as a means of travel between locations on ice skates or windpowered ice sleds. Travel between planets was like traveling on a passenger ship, a familiar and regular means of travel during the years before air travel became commonplace. In Heinlein’s world, mathematical calculations were done using an analog calculator, the slide rule (sometimes called a “slipstick”). These two stories could be interesting reading for young people because they present a very different world relative to the present day, a world that is a less technologically dependent society.

Podkayne of Mars was published in 1963 and features a 15-year-old (Earth years, or 7½ Mars years) Podkayne and her younger brother Clark (11 Earth years old, or 6 Mars years). Join the precocious pair as they leave their home on Mars for the first time on a trip to Earth by way of Venus with their uncle. Things take a turn when Clark is kidnapped on Venus and Podkayne gets involved.

The Red Planet, published in 1949, is about the colonists living and working on Mars under conditions like a “company town.” Under those circumstances, places where people worked, lived, and probably shopped were owned and governed by the Earth-based company. The principal characters in this story are Jim and Frank, two young men. Also, there are Martians in this story. Jim has a ball-shaped native Martian companion nicknamed “Willis the Bouncer” because of how it moves about. Willis is friendly and has a unique habit of repeating what is heard much like a parrot would do. Jim, Frank, and Willis live in a residence hall while attending a boarding school in a city some distance from their families. There, Jim and Frank overhear a sinister plot against the colonists by the colonial administration. During their efforts to alert the colonists, Jim and Frank meet other Martians, the “Old Ones,” adult versions of Willis, who the boys find out is a young Martian. With the help of the Martians, the people fight back against the colonial administration and gain their independence.

For students

- Back in the “old days” before the electronic calculator, mathematical calculations were often done using a slide rule. What is a slide rule and how does it work?

- What is cosmic dust or interplanetary dust and where do astronomers believe it comes from?

- If you are reading Red Planet, listen to the song “16 Tons” and read the lyrics. How is the theme of the song similar to the theme of the book, especially the colonists?

- Plot the 2020 retrograde path of Mars.

For teachers

What was science fiction like during the time when Robert Heinlein wrote Red Planet? To get an idea, look at the sci-fi fanzines my late father wrote and published in the years after World War II (see Peon in Resources).

Visible planets

| Visible Planets | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Zodiacal light

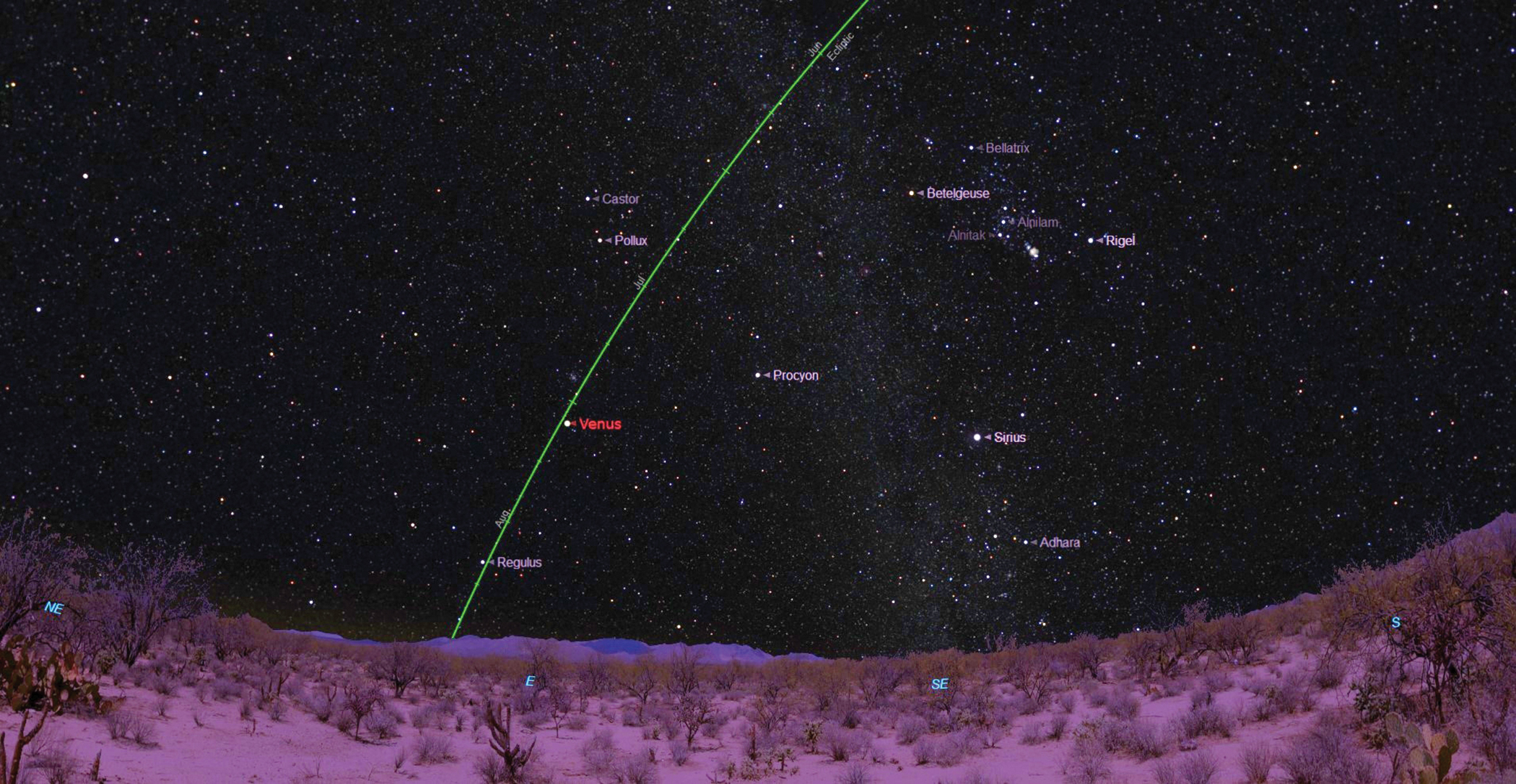

Sometimes referred to as the “false dawn,” zodiacal light looks like a triangular-shaped shaft of dim diffuse light rising from the horizon. The zodiacal light is made by the reflection and scattering of sunlight by the exceptionally fine dust particles called cosmic dust. Thought to be composed of particles created by collisions between comets, zodiacal light can best be seen around the two equinox dates. Around the March equinox, in either hemisphere, the zodiacal light is most prominent rising over the western horizon after sunset. Conversely, around the September equinox, the zodiacal light is most prominent rising over the eastern horizon before the Sun rises. These two specific times of the year for the zodiacal light occur because at around the date of the equinox, the plane of the ecliptic is at its most vertical position relative to the horizon and the zodiacal light (see Figure 3).

Morning sky showing the ecliptic

Seeing the zodiacal light requires a very dark and moonless sky. If the sky is dark enough to at least see the Milky Way rising over the eastern horizon, then you should be able to see the triangular-shaped diffuse glow of the zodiacal light. The light is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye or captured with a camera, but the zodiacal light is too diffuse with no discernibly defined edges to be seen with binoculars or telescopes. This year the prospects for seeing the zodiacal light should be good, as the Moon will not be interfering because it will be in the waxing phases and setting during the evening hours. The morning skies, however, may be somewhat brighter as the inner planet Venus will be shining over the eastern horizon before sunrise (see Figure 4).

The zodiacal light

30 Revolutions

A long time ago, but in this galaxy, the first official Scope on the Skies column appeared in the September 1990 issue of Science Scope. This followed positive feedback from two ‘test’ columns published the previous spring. That was 30 years and 249 columns ago! Along the way I have had wonderful opportunities as I collaborated with several assistant editors, a couple of field editors, and longtime friend and colleague former managing editor Ken Roberts. I have learned a lot about writing and about Earth and space as well as other sciences. I can only imagine how much learning was taking place on the editorial side. They always caught me when I would try to slip in an April Fools joke in that monthly issue!

“Where do you get your ideas?” students have asked me during career day presentations. I tell them that I look at and listen to the world around me, earbuds or headphones not included. My ideas come from reading, from being curious, and from asking questions. Asking questions oftentimes leads to what I especially enjoy, which is learning about something and then being able to share it through my writing. Have I run out of ideas? With the universe to write about—not yet.

| September | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| October | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bob Riddle (bob-riddle@currentsky.com) is a science educator in Lee’s Summit, Missouri. Visit his astronomy website at www.bobs-spaces.net.

Astronomy Earth & Space Science Middle School