Brief

Accessible Making and Tinkering

Ensuring the Inclusion of People With Disabilities

Connected Science Learning July-September 2018 (Volume 1, Issue 7)

By Charlotte Martin

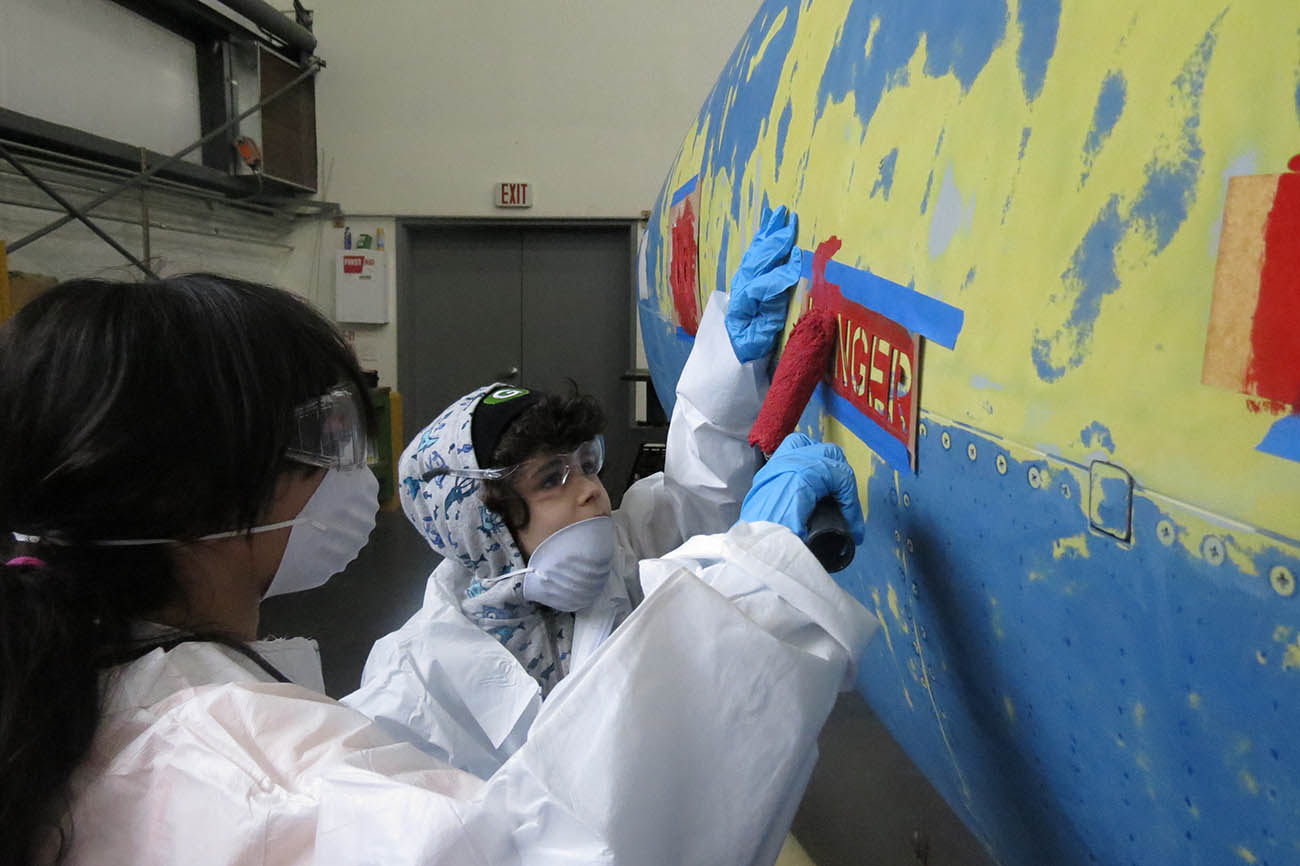

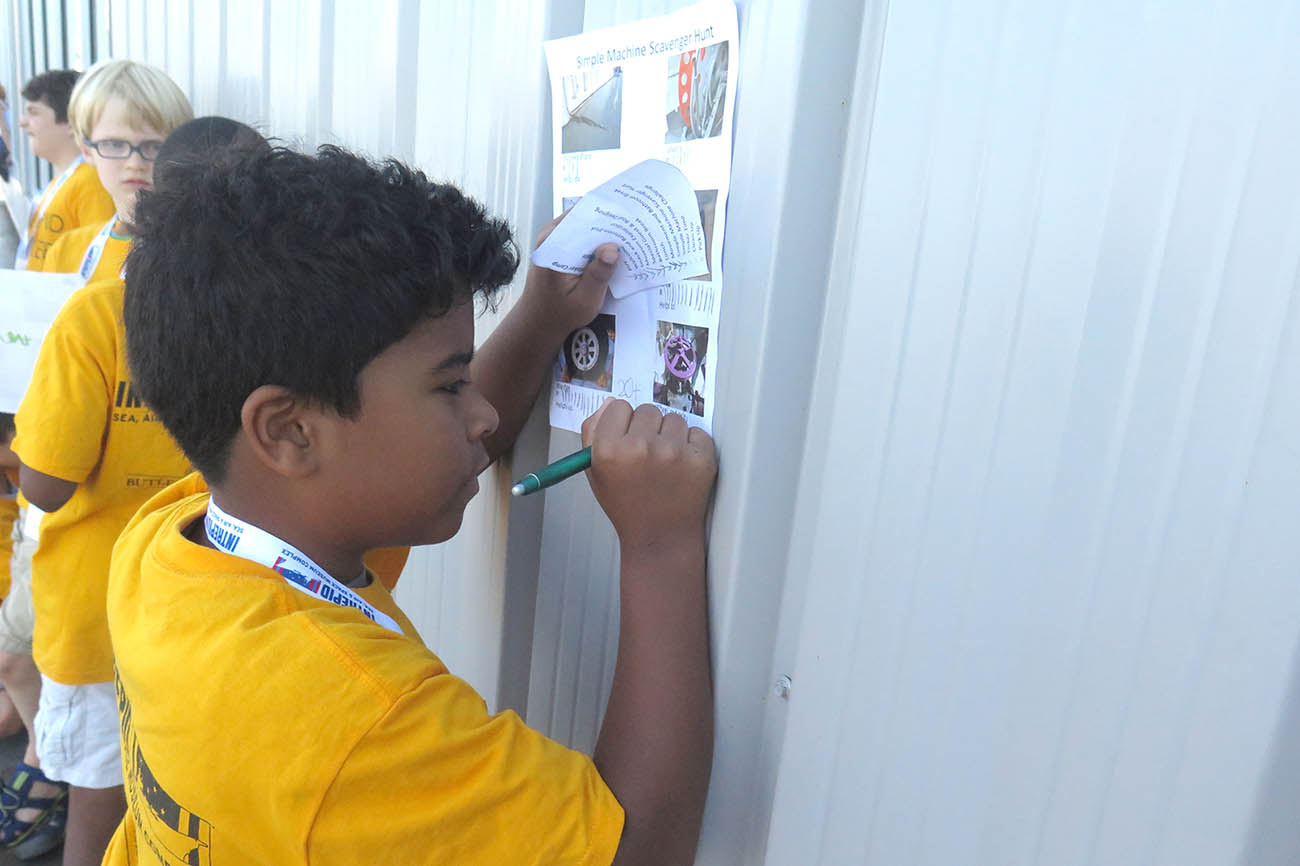

Maker spaces and programs offer tremendous opportunities for all learners to explore new materials, expand their practical skills, think creatively, and exercise social-emotional skills such as problem-solving and collaboration. With this in mind, in spring 2016, the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City launched All Access Maker Camp, a weeklong camp for children ages 8 to 14 with developmental disabilities. We saw an opportunity to connect children’s strengths and passions for space, aircraft, LEGOs, history, drawing, and computers with a supportive space for authentic exploration, experimentation, socializing, and personal growth.

The Intrepid Museum’s program is specifically for children with disabilities. However, all maker programs and spaces should be accessible to and inclusive of people with disabilities. No one should be excluded from expanding their skills, deepening their interests, or sharing their expertise because of physical, communication, or emotional barriers. And because of their multisensory and exploratory nature, maker spaces and programs start in a great position for inclusivity.

When planning for accessibility and inclusion, it is important to think about the barriers that exist in your space, whom they may exclude, and how you can break down these barriers without compromising your program goals. Often this means building multiple entry points and avenues of experience. These options benefit not just those with specific disabilities, but all participants.

Every maker space and program is different, but in general, here are some barriers and strategies we learned from our experiences that are important to consider:

- Communication: Use multiple modes of communication to ensure that all makers can get the information they need and share their ideas and questions. Break down instructions into individual steps for those who have difficulty with working memory or language processing. Some people need more time to process information, so be patient and give everyone a chance to interpret and respond.

- Attitude: Low expectations or a dismissive attitude can be detrimental to any learner. Rather than focusing on deficits, maintain an open mind and hone in on strengths as a starting point. Encourage makers to move beyond their comfort zone by providing a supportive and safe environment.

- Safety: People with disabilities and their families may have especially strong concerns about safety. These concerns may stem from a physical disability, struggles with impulse control, difficulty understanding complex or multistep instructions, or past negative experiences. As always, ensure that areas meet at least the minimum requirements set by the Americans with Disabilities Act so that anyone can effectively navigate spaces free of hazards. All instructions and safety information should be clearly expressed in multiple ways. Make sure all personnel know and enforce safety protocol.

- Tools and materials: Ensure you have a variety of materials and tools available so that makers with motor delays, limited mobility, low muscle tone, or difficulty with spatial reasoning have options. Use authentic tools, but consider adjusting the sizes of tools or adding supports that make them easier to maneuver effectively and safely. Be patient with makers challenging themselves to use a material with which they struggle. Some people are also sensitive to specific textures, so consider a variety of material types (e.g., for a sewing station, include a variety of fabric options).

- Collaboration: Maker spaces and programs are a great opportunity for people with common interests to meet and socialize. For someone with a very deep and specific passion who has a hard time engaging with others, these connections can be especially important. Include opportunities for both informal and formal collaboration. Individuals with autism may have difficulty recognizing and interpreting social cues, but shared interests and goals can be strong motivations to work through conflict.

- Planning and expectations: Letting participants know what to expect can help reduce anxiety and adjustment time for those with autism (but also for anyone), as changes in routine and encounters with new people can be difficult. Create and share a simple photo-illustrated social narrative in advance to give makers the chance to prepare for new experiences (see Supplemental Resources for the social narrative used by the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum). Make sure that rules and norms are clear and consistent and that staff are comfortable explaining the reasoning behind them.

- Environment: An immersive maker experience can be a barrier for those with sensory processing disorders, such as extreme sensitivity to loud noises, or those who are easily distracted. Providing inexpensive noise-reduction headphones or earplugs can ease discomfort and increase concentration. Workspaces should be well-lit, but research the type of lighting preferred by individuals with light sensitivity. Whenever possible, try to minimize odors. Let makers know where the quieter areas are and where they can go to take a break.

The success of these strategies relies on the people who develop and staff the spaces and programs. Training is essential and will benefit all participants. Consider connecting with local disability service providers, consultants, self-advocates, and accessibility consortia, and be open and responsive to feedback.

Charlotte Martin (cmartin@Intrepidmuseum.org) is manager of access initiatives at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York, New York.