Diversity and Equity

Head Start on Engineering

Teachers, Informal STEM Educators, and Learning Researchers Collaborating to Engage Low-Income Families With Engineering

Connected Science Learning October-December 2017 (Volume 1, Issue 4)

By Scott Pattison, Gina Svarovsky, Ivel Gontan, Pam Greenough Corrie, Marcie Benne, Shannon Weiss, Verónika Nuñez, and Smirla Ramos-Montañez

The Head Start on Engineering project engages parents and children in a multicomponent family engineering program that includes professional development for teachers, workshops for parents, take-home family activity kits, home visits, classroom extensions, and a culminating field trip to a science center.

Throughout their lives, children from low socioeconomic backgrounds and traditionally underserved and under-resourced communities face significant barriers to engaging with engineering and science (Gershenson 2013; Orr, Ramirez, and Ohland 2011). Supporting learning and interest development in early childhood, and engaging families, preschools, and community stakeholders in this process, is a powerful way to address these issues and a critical economic investment to ensure children become productive members of their communities (Garcia et al. 2016). Although not often a focus of early childhood education, engineering and problem-solving skills are increasingly recognized as essential for children and adults to thrive in today’s society and are a growing part of the K–12 curriculum (NGSS Lead States 2013). Introducing families to the topic of engineering and sparking young children’s interest in planning, building, testing, and problem solving helps prepare them for school and life.

In this article, we introduce the Head Start on Engineering (HSE) project, which was designed to address these challenges through a multicomponent, family engineering engagement program integrated with the Head Start model. Head Start is a federal program within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that promotes school readiness for young children (birth to age five) from low-income families through child care centers and home visiting programs in communities across the country. HSE fosters connections across preschool and family learning contexts to catalyze long-term, enduring family interests related to science and engineering—or what are often called long-term interest pathways.

Program Description

HSE is a multicomponent program integrated into the wrap-around services of Head Start. It is designed to prepare low-income families with young children (ages 3 to 5) for a world where science and engineering are now ubiquitous. The project is a research-practice partnership involving the Institute for Learning Innovation (ILI), Mt. Hood Community College (MHCC) Head Start, the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), and the Center for STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) Education at the University of Notre Dame. Each partner provides unique expertise in family learning, community engagement, early childhood education, or engineering. HSE is founded on prior research, built on strong community involvement, and designed to catalyze system-level changes in how low-income families are supported, including how community partners work together to collectively support early childhood STEM learning.

The program provides comprehensive services for parents, children, and their teachers, including professional development (PD) for preschool educators, hands-on engineering activities for families, parent workshops, preschool classroom curricula, and rigorous assessment and program improvement. In the short term, HSE is designed to:

- develop families’ interest in engineering,

- increase parents’ and children’s engineering and design thinking skills, and

- support other early childhood development outcomes, such as numeracy and early reading skills.

Over the long term, we aspire to help children and their parents develop enduring interests in and seek out future learning experiences related to engineering to shape children’s performance in school, engagement in extracurricular activities and hobbies, perceptions of themselves, and aspirations for future careers.

We believe the story of how HSE developed, and continues to develop, is as important as the program itself. The HSE partners, with ongoing community guidance through formative assessment and Head Start parent and staff input, have worked to develop and pilot this program since 2013, using principles of community-based participatory research (e.g., Hacker 2013; Israel 2013) and asset-based perspectives on learning and education (e.g., Gutierrez and Rogoff 2003; Lemke 2001). In 2013 staff at ILI worked with senior leaders at MHCC Head Start to conduct a pilot research study on families’ perspectives on science, and how parents with young children build science-related interest pathways through experiences at Head Start, at home, outdoors, and in science centers (Pattison 2014; Pattison and Dierking, forthcoming).

Based on these initial findings, we launched the two-year, National Science Foundation (NSF)–funded Head Start on Engineering pilot project to develop and test the program and continue to explore how early childhood science and engineering interest develops for families inside and outside of school. Throughout the pilot, we gathered input from families to understand their perspectives on engineering, their priorities for their children’s learning, and their goals for participating in the project. Critical collaboration and input-gathering activities have included front-end surveys with Head Start teachers and families, partner “learning dinners” to share expertise across organizations, and parent and teacher reflections integrated into program activities. This long-standing partnership has allowed team members to build trust and understanding with each other and the community and ensure that the HSE program serves the needs of low-income families. As a research–practice partnership, the complementary expertise and capacity of each organization—including learning research (ILI), family engagement (MHCC Head Start), informal STEM education (OMSI), and engineering (Notre Dame)—were essential for moving the project forward and creating a more impactful program than any one organization could have supported alone.

Research Foundation

Based on our pilot studies, we have developed a program model that continues to guide implementation. The HSE program builds on a substantial body of early childhood STEM learning research (e.g., NASEM 2016; NRC 2000) and draws from a variety of theoretical perspectives, such as asset-based education approaches that build on existing strengths and knowledge within communities, ecological perspectives that account for the multiple contexts and experiences influencing learning and development (e.g., Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2007), and emerging research on engineering engagement in preschool (e.g., Dorie et al. 2014). At a basic level, however, the program is founded on two research-based principles:

- To truly understand and support STEM learning and interest development in early childhood, it is essential to consider the whole family as a holistic learning system (Pattison et al. 2016).

- To foster long-term, resilient STEM learning and interest pathways for young children and their parents, integrated program models are needed that touch on multiple aspects of families’ lives, inside and outside of school (Bronfenbrenner 1979; NRC 2009).

Departing significantly from past conceptualizations that focus primarily on the child, our approach frames interest development as a distributed, family-level phenomenon that is characterized by shifts in beliefs, behaviors, and resources for both children and parents. Although researchers and educators often think about parents and children separately, as in cases where they focus on child outcomes and consider parents to be an important “contextual” factor, research actually suggests that early childhood development is highly transactional—with parents and children continuously influencing each other—thus making it difficult or impossible to determine the directionality of influences among family members (e.g., Hume, Lonigan, and McQueen 2015; Sameroff 2009). This reciprocal relationship between children and adults, especially primary caregivers, has long been understood as a central component of development (IOM and NRC 2012; NRC 2000).

For example, an HSE activity might spark a child’s curiosity about building towers, which increases parents’ awareness of the child’s developing interests and motivates them to seek new experiences and resources related to building. Conversely, an HSE parent workshop might reinvigorate a parent’s joy of designing and building, which she can communicate to her child through her excitement and engagement with an HSE home-based activity. That enthusiasm might lead the child to ask for similar experiences in the future. For us, the directionality of these relationships is less important than understanding the ongoing changes across family members. Above all, the goal is to support the family system, including parent beliefs and attitudes, child interests and behaviors, parent–child interactions, and family experiences and resources, as parents and children engage in a mutually reinforcing process of learning and interest development.

Not only should programs support the family system, but they must also consider the ways families learn across many contexts, inside and outside of school. As decades of research have shown, learning happens within the broad ecology of families’ lives, including daily childhood interactions with parents and other significant adults; the context of children’s home, preschool or child care, and other learning environments; and the broader influences of the culture and society. Researchers now understand that to significantly impact learning and development, multiple aspects of these ecologies should be addressed, as when a program links experiences inside and outside of school or supports children and families in making connections across learning moments throughout their lives (NRC 2009). This may be especially true for interest development, because early sparked interests must be supported over time to develop into more robust, individual interests that motivate ongoing engagement and learning (Alexander, Johnson, and Leibham 2015; Hidi and Renninger 2006).

Based on this research, HSE takes a holistic approach to family learning, not only engaging children, but also supporting parents and early childhood educators. The project combines multiple experiences across a variety of contexts, including the home, the preschool classroom, parent education events, and the science center, to support positive growth in all aspects of family learning—with a particular focus on supporting parent–child interactions outside of school. Although early childhood STEM programs often focus on the classroom, decades of research show that at this early age, parents are the primary influence on children’s learning and development (NASEM 2016; NRC 2000) and a critical leverage point for influencing children’s long-term interests and career aspirations (e.g., Dorie et al. 2014; Matusovich, Streveler, and Miller 2010).

Program Model

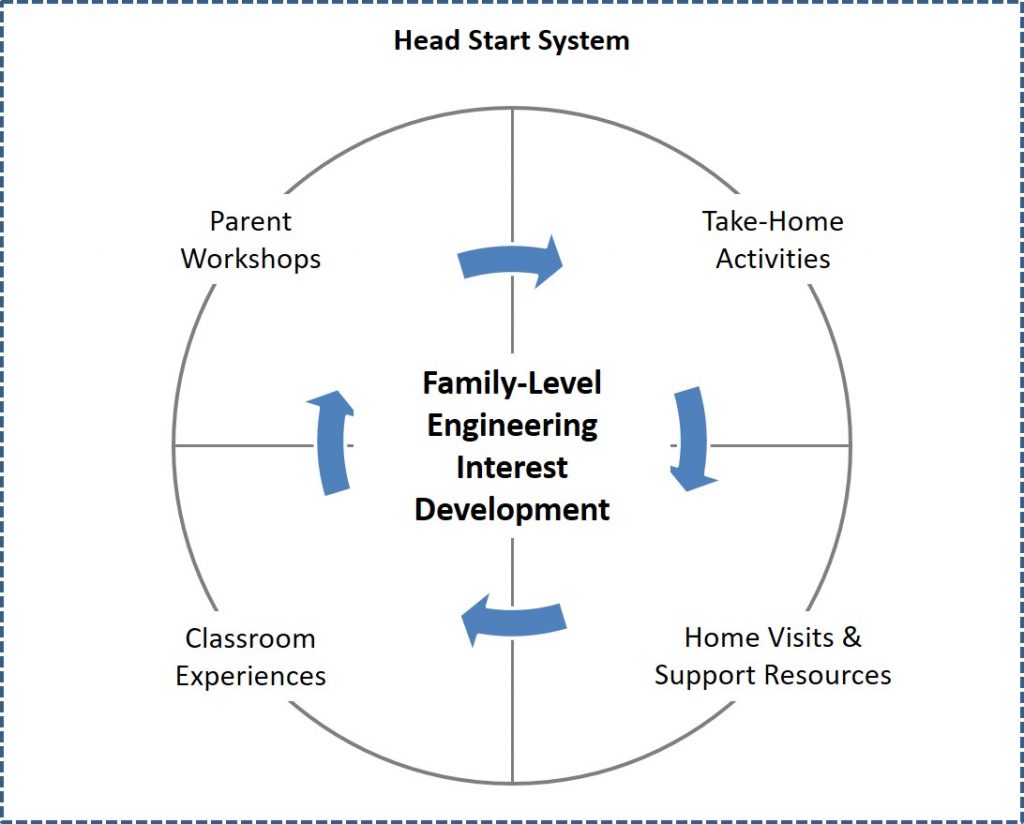

What does a program look like when it conceptualizes early childhood interest development as a family-level phenomenon and integrates multiple experiences across contexts for parents and children? The current HSE program includes several key components designed to support Head Start and science center staff, parents, and children developing long-term interest pathways related to engineering (see Figure 1).

The backbone of these components is a set of four bilingual (Spanish and English) family take-home engineering kits. Each centers on a hands-on engineering design challenge and includes:

- a bilingual storybook carefully selected to launch the activity and create a context for the engineering process;

- simple materials that parents can easily reuse, replace, and supplement; and

- a parent facilitation guide with instructions, facilitation tips, and extension ideas.

For example, the first activity kit provided to families, called the Fox and the Hen, challenges parents and children to work together to build a tower of foam blocks that is over one foot high. To set the context, the family reads a story about a group of hens looking for ways to protect their nests from a fox. After reading the book, families work on building a tower to protect the nest from the fox and test their design by seeing whether it is taller than a one-foot high cardboard image of a fox, which is included in the kit.

From there, families can extend the activity in a number of ways, using the story context to motivate ongoing design, testing, and revision. For example, children often enjoy thinking about how to ensure the tower is protected from foxes that can dig, or giving hens an escape route. The other kits use a similar structure involving a story and engineering challenge, such as building a set of tubes to help a mouse (i.e., Ping-Pong ball) escape from a cat and get back to her family and creating a nest that will let a bird and her eggs perch safely in different locations (e.g., the top of a cup or bowl). Guided by prior work at the University of Notre Dame on family engineering engagement (e.g., Cardella, Svarovsky, and Dorie 2013), each kit was carefully designed to provide at least two clear, compelling design challenges, based on the story and characters in the books, that help families move beyond exploration of materials and begin to incorporate aspects of the engineering design process, such as problem scoping, planning, and iteration.

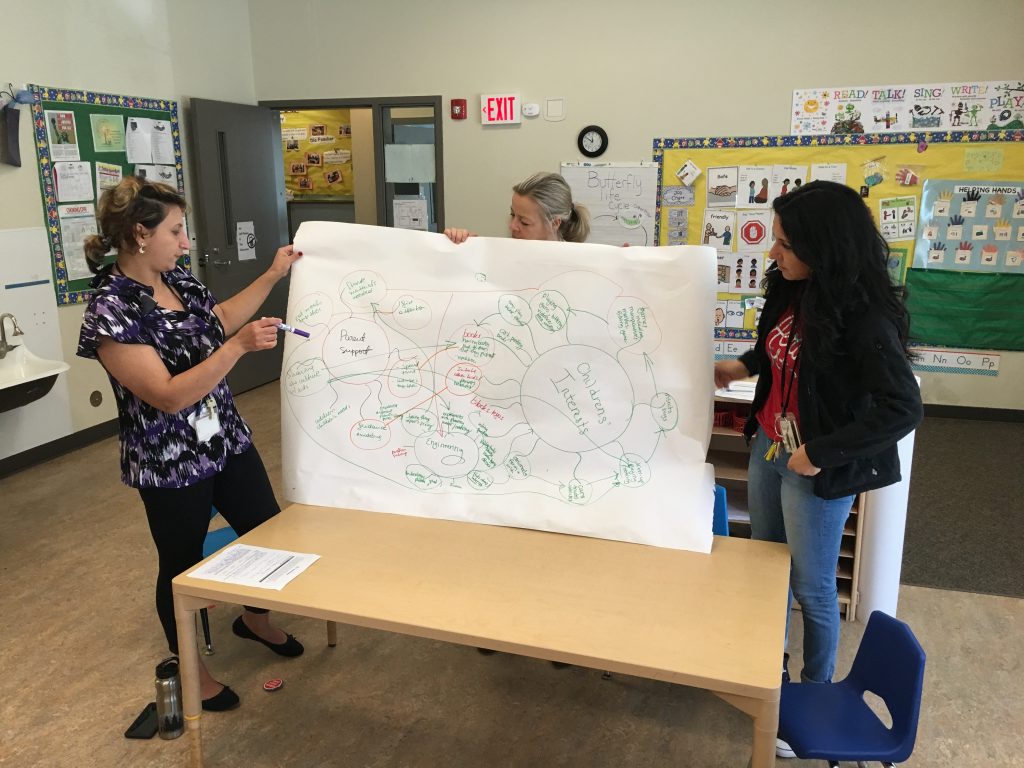

These activities are the anchors for the array of HSE program components integrated within the Head Start model. In the pilot conducted during the 2016–2017 school year with one MHCC Head Start location (approximately 40 families), the program began with a series of three PD workshops for partners and Head Start teachers to introduce them to engineering and give participants hands-on experiences with the kits. Drawing on the PD techniques and activities used to develop preK–12 educators’ engineering capacity in other programs (e.g., Cunningham and Lachapelle 2010), the sessions included hands-on design challenges, reflections about the design process and its relevance to everyday contexts, and an introduction to the HSE activity kits. The sessions also built on preliminary discussions with a subgroup of Head Start teachers and staff during the first year of the project, during which the team developed a shared understanding of the engineering design process and explored how it could be applied to family learning in early childhood.

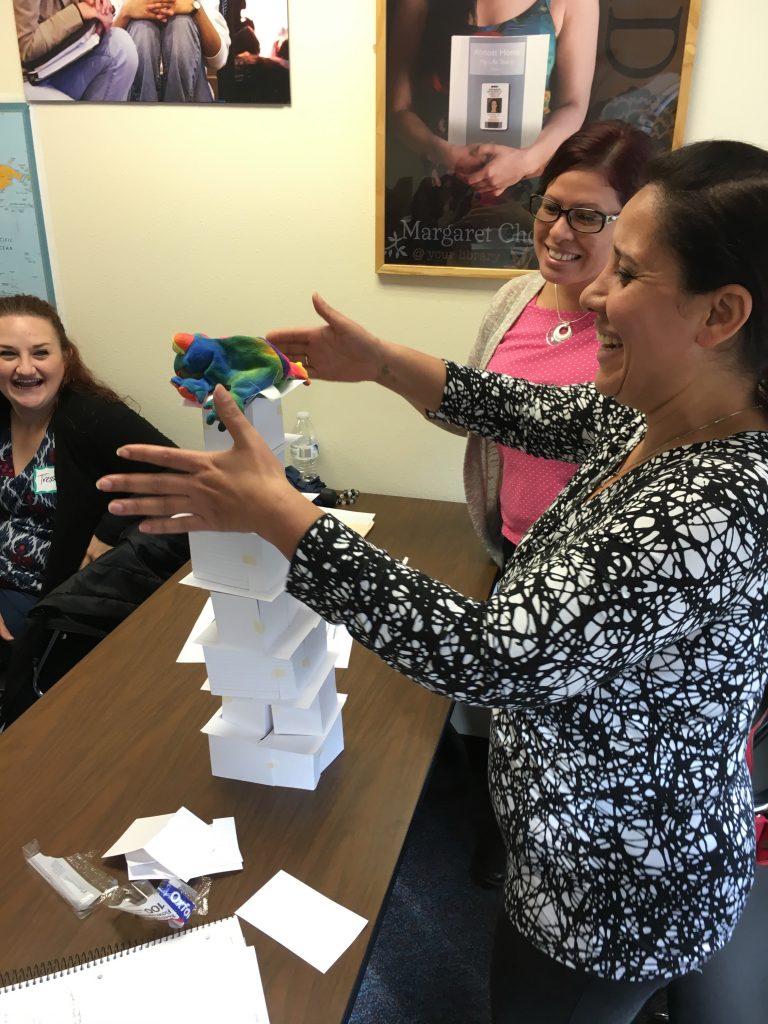

Next, the family experiences component of the program launched with a family engineering night at the Head Start location, held during one of the monthly Head Start parent meetings, when families at each Head Start location are invited to come for dinner, updates, and social learning opportunities. The engineering night included dinner, an introduction to engineering, time to explore and discuss the Fox and Hen activity, and practice looking at other children’s books and thinking about engineering design challenges for each story. A group of these families (nine during the pilot phase) was then recruited to participate in three separately scheduled evening parent workshops. During these workshops, program staff shared more about engineering with parents, introduced and let parents explore each activity kit, discussed strategies for engaging their children in the activities, and facilitated conversations among parents about their experiences with the kits at home. The team also introduced parents to a version of the engineering design cycle (ask, imagine, plan, create, improve) and continually revisited this cycle to help parents and staff become more familiar and comfortable with the design process. After each workshop, parents took home their own copies of the activity kits introduced during that meeting.

In between the parent workshops, Head Start staff and OMSI and ILI researchers made regular home visits to the families, aligned with the Head Start program home visiting model, to collect input from families in a space that was convenient and comfortable for them and to better understand how the program was impacting learning at home. They gathered feedback from parents on the activities and program, videotaped parents and children engaging with the activities together, and explored how the activities were sparking family interests related to engineering. Head Start teachers who participated in the project also brought several aspects of the kit activities into their classrooms, individually adapting the materials to their own teaching and curriculum goals. Teacher implementation ranged from reading one of the books to their students, to engaging them in the kit activities, to using the kits as a foundation for further exploration of materials and design challenges. The year ended with a field trip to OMSI, during which all of the families and staff members from the MHCC Head Start pilot location were invited to explore the museum, engage with engineering exhibits, and become comfortable with OMSI as a space for family learning. During the field trip, families and Head Start staff had dinner in the science center and then explored the exhibit halls, including the recently installed Designing Our World exhibition focused on engineering.

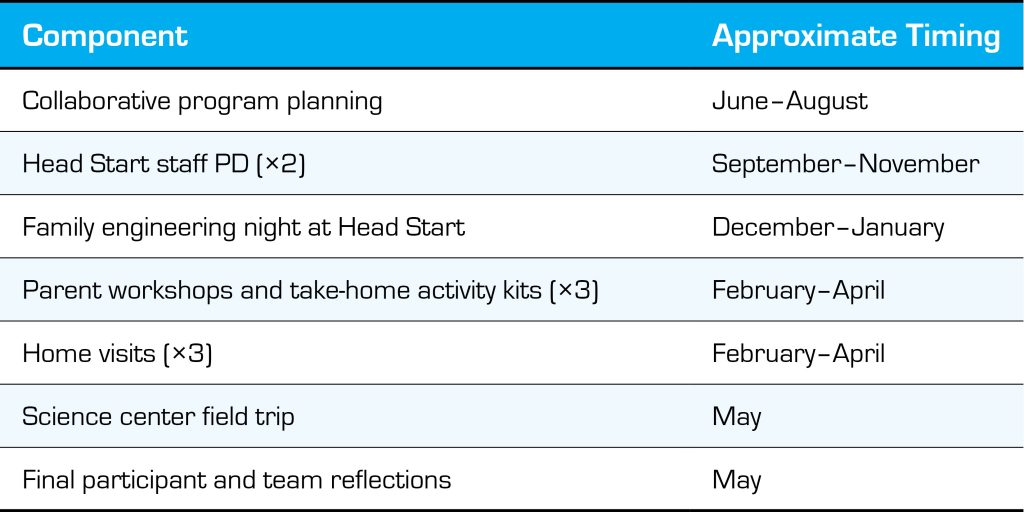

Figure 2 shows an overview of the primary program components. Across all events and activities, the materials were provided in Spanish and English, with attention to the literacy needs of Head Start families. The parent workshops were also presented in both languages by bilingual OMSI staff members.

Preliminary Research and Evaluation Findings

Two years of NSF funding have allowed us to test the program model and to begin to understand its impact. The pilot project included both evaluation and research components to inform ongoing program improvements, understand the impact on families, and build knowledge of engineering interest development in early childhood using a family-level perspective. Below, we describe preliminary findings from each aspect of the project and insights about how families engaged with and responded to the integrated HSE program model.

Evaluation during the pilot phase included pre-program surveys with parents across the MHCC Head Start program (beyond the specific implementation site), post-program surveys with program participants, and in-depth interviews conducted by Head Start family workers with each participating parent. Participating families expressed a strong interest in continuing with the program and making sure it was available for families next year. In post-program surveys, 100% of participants said that they were very likely to recommend this program to other families, and all of them indicated they were very likely or likely to continue engaging in learning activities related to the program with their children, including using the activity kits and reading the books at home, talking about engineering with their children, and seeking out new experiences and resources related to engineering for their family. In comparison with responses from the broader group of Head Start parents, pilot program participants were more likely to value engineering as very important for their children and to indicate that they were very comfortable engaging their children in engineering activities.

During the final interviews with participants, parents were asked to describe their experience overall with HSE and to suggest possible program improvements. The responses from the families indicated that program impacts went well beyond engineering. For example, one of the most positive aspects of the experience was the discovery of new ways to structure play with their children, such as using the engineering design process, engaging in open-ended exploration, or connecting books with hands-on activities. The families also indicated the value of repurposing household materials in creative ways, and parents reported being eager to create new engineering design challenges to engage their children. Almost all parents reported a broader understanding of engineering and some suggested that the program had increased their communication as a family and given them a new perspective on the ways their children learn.

Parents also shared their ideas for program improvement. Several parents emphasized the importance they saw in making the program inclusive of the whole family and supporting interactions between parents and children. For example, parents said that although they valued the adult-only approach to the parent workshops, they would have liked time to practice the engineering activities with their children when program staff members were available to help. Similarly, parents were also interested in more ideas to help facilitate the activity kits and find ways to extend children’s ongoing interests. One participant said that with her educational background and reading level, it would have been helpful to present the materials in multiple formats (e.g., videos and more hands-on practice) to complement the workshops and written instructions, and to use the follow-up home visits to not only collect feedback but also answer outstanding questions about the program and take-home activity kits.

Example Research Case Studies

Beyond letting us develop and pilot a new program, the last two years of the project were used to document how HSE children and their families foster interest pathways related to engineering. Throughout program implementation, researchers from OMSI and ILI gathered in-depth data from 15 participating families, including:

- home visits and interviews with parents and children before and after each parent workshop,

- videotaping of parent–child interactions with the take-home activity kits,

- teacher journals of classroom activities and children’s developing interests, and

- end-of-year reflective discussions with parents.

The following case studies illustrate how the HSE program impacted two family groups. (Note: All participant names in this article are pseudonyms.) In both cases, the families engaged in engineering design thinking at home, including problem scoping, designing solutions to engineering challenges, and using the storybooks as the basis for imaginative play. The examples emphasize how the process of interest development for young children and their parents is truly a family-level phenomenon, with parents, children, and other family members all influencing each other as they participated in the program and then broadened their engagement to other aspects of their lives. The examples also highlight the complex nature of early childhood STEM interest development, which rarely focuses exclusively on a single content domain but instead touches on a variety of topics, activities, and family preferences (Azevedo 2011). Although these case studies are representative of other participants in the pilot program, it remains to be seen how well the experiences of the small group of families generalize to the broader Head Start community.

Luisa and Carolina

Luisa and her four-year-old daughter Carolina are Latina and speak Spanish at home. At the time of the program, Luisa was pregnant with her fourth child, a baby brother for Carolina. Carolina also has two older sisters (seven and eleven). Luisa was employed as a housekeeper, and Carolina’s father worked multiple jobs to support the family. Luisa was very involved in the program and attended all of the HSE parent workshops. During the interviews, she indicated that she frequently played with the activity kits, both with Carolina and the whole family. According to monthly journals, Carolina’s teacher also regularly used the activity kits in the classroom, reinforcing what the family was doing at home.

Luisa seemed particularly interested in exploring how Carolina could use her imagination during the activities. For example, they might imagine a house for the hen in the Fox and Hen activity, then build rooms in the house, then decide they need a door for the hen to escape. Luisa said that she appreciated how this type of play created space for her child’s growth and development, and she noticed the effects on Carolina being able to think critically about a scenario. Similarly, Luisa noted that when playing with her daughter, she began to appreciate the importance of providing space for Carolina to make mistakes and come up with different solutions. According to Luisa, the program was helping her see what was developmentally appropriate for her child.

Luisa also expressed interest in playing a more active role in her child’s development, especially using design challenges such as those in the HSE kits, which could be cheaply created. The parent workshops and HSE activities inspired her to invent other challenges for the family to help motivate learning. She also noted that the activity structure was having an effect on how her children played together. For example, the older siblings were more inclined to let Carolina figure something out for herself instead of telling her the answer. Luisa herself realized through her involvement with HSE that exploration is part of learning and tried to engage in more open-ended play with Carolina.

Molly and Charlie

Molly and her grandson Charlie both speak English at home and, at the time of program, lived with Molly’s two adult sons, who were 19 and 21. Molly said that even before becoming involved in the program, she was interested in arts and crafts and often engaged Charlie in those types of activities. The family attended all of the HSE parent workshops and participated in three home visits. From the beginning, Molly was excited about the program and supported Charlie in doing the engineering activities several times a week. According to her, Charlie loved the activities, and they would often go to the library to look for other books that would inspire new engineering challenges. They even talked about building a special shelf to store the HSE kits at home. Molly said that Charlie always wanted to read the stories when they did the activities and that she was discovering new ways of relating to her grandson through the program.

According to interviews, Molly and Charlie particularly appreciated the structured playtime afforded by the take-home kits. During the home visits, Charlie seemed to know exactly in what order they were going to go through the steps of each activity. In these video recording sessions, Molly often played a strong role in guiding the flow and direction of the experiences, asking Charlie questions and supporting him when their designs were not successful. Molly stated that the activities helped her realize how hard it can be for a boy Charlie’s age to manipulate blocks and other materials. She credited the program with helping her become more attuned to Charlie’s limitations and how she could support him. Similarly, she described how her patience as a caregiver had increased through the program.

Even more than Luisa and Carolina, for Molly and Charlie there was a strong connection between what was going on in the Head Start classroom and what was happening at home. In her monthly journals, Charlie’s Head Start teacher reported regularly using the activities, which she said were enjoyable for the children. During the home visits, Molly indicated that Charlie regularly played with the kits at school and would come home with new ideas about how to use the materials. According to her, he even liked to show other children and his friends how to use the kits. For Molly and Charlie, as well as other families, this new role of teaching the activities to others may have represented an important step in interest development as the families built their confidence with the activities and the engineering design process.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

As with any educational program, Head Start on Engineering faced a number of challenges and uncovered a number of intriguing research findings. Below, we outline several lessons learned that are informing the next phase of the project and may benefit other educators and researchers in the field who are working on similar efforts.

Lesson #1: Designing Activities to Engage All Family Members

Interviews with parents and initial analysis of videotaped parent–child interactions highlighted how the project activities often engaged the whole family, including spouses and partners, siblings, family friends, and extended relatives. The authentic and pragmatic use of these materials in different family configurations led several participants to report that a key success of the program was not only providing engaging activities that all family members could participate in at home, but also how having ready access to these activities could catalyze periods of focused family time and attention. Given the busy schedules that Head Start families must often accommodate, purposeful and enjoyable family time around these activities was reported by multiple families to be a benefit of the program. In the future, we hope to more intentionally design elements of the activities to support this whole-family engagement. Similarly, other programs seeking to engage families may incorporate strategies for supporting multigenerational, whole-family learning, such as suggestions to parents for ways that they can facilitate the activities for both their preschool children and older siblings.

Lesson #2: Leveraging the Enthusiasm of Head Start Teachers

Although we knew from the start that the Head Start teachers were critical to the success of the program, findings from the pilot study and reflections from the project team emphasized the central role that the teachers played in ensuring buy-in from families, generating excitement, and making connections between the home and the classroom. In the future, we hope to strengthen the role that these teachers play by providing more explicit opportunities for teachers to co-lead parent and staff workshops. We also hope to provide more time for teachers to talk with their colleagues about ways to adapt the kits to the classroom and support connections with family learning at home, as requested by staff during the end-of-year reflections. Other early childhood programs engaging teachers may consider ways in which these professionals have opportunities to use elements or ideas from the project as a catalyst for their own work in the classroom.

Lesson #3: Extending Program Impacts

Through evaluation surveys and interviews, participating families expressed a strong interest in continuing with the program and making sure it was available for families the following year. We learned that families were eager for more ideas about how to support their children’s ongoing engineering interest development and go beyond the HSE activities to new experiences or topics, engineering-related or not. In addition, families suggested incorporating more videos into the experience to help parents, especially those with low literacy levels, understand how to use the kits and see examples of other parents motivating and facilitating their children’s engagement. Other projects with a similar emphasis on family learning may benefit from developing more specific resources to support families in continuing their interests beyond the program.

Lesson #4: Creating Imaginative Engineering Contexts

Each of the engineering activities used in the program is based on a playful storybook intended to help introduce the engineering design challenges. During the pilot we experimented with a variety of books connected to the activities. One intriguing finding from the research study was that the books with a clear, compelling story, with characters that the family could relate to, seemed particularly good at motivating engineering engagement at home and helping parents make connections between the book and the engineering design process. In future iterations of the project, we may look for new books to replace some of the ones used in the previous versions of the activity kits. Based on parent feedback, we will also use bilingual books or add stickers with the Spanish text on each page, which were more popular formats with families compared to separate English and Spanish versions. Overall, we believe this connection between children’s books and STEM engagement will be a central element for the program moving forward, and potentially a critical approach to early childhood STEM learning for the field to consider more broadly (e.g., Hojnoski, Columba, and Polignano 2014).

Conclusion

Although there is a growing number of early childhood STEM education programs, we believe HSE is unique in its focus on the family interest system and its approach to creating a set of closely linked, integrated experiences for families across settings, including teacher PD, parent workshops, home-based experiences, classroom activities, and science center visits. The program also focuses on supporting low-income families by integrating with the wrap-around services of Head Start to address the unique challenges these families face.

Preliminary findings suggest that HSE is a strong program model, with implications for early childhood STEM education efforts across the country. Participating families were enthusiastic about the experience and reported a variety of positive outcomes, including increased interest in and value for engineering, ongoing and self-motivated engagement with engineering activities and resources at home, growing awareness and learning related to parents’ roles facilitating learning for their children, and more. The in-depth, qualitative case studies demonstrate that the integrated set of program experiences across contexts can build ongoing interest development and learning pathways that move beyond the specific program materials and resources, such as parents and children seeking out other books to inspire new engineering activities at home, or families incorporating other adults and siblings into their engineering learning experiences. These findings shed light on the potential of early childhood engineering interest development and suggest ways that researchers and educators can partner to foster these types of experiences within other communities and across different STEM content domains. The findings also highlight outstanding questions for future investigation, including a need to better understand how storybooks support family STEM engagement, as well as identify the mechanisms and resources that motivate families to go beyond the program materials and begin broadening their engineering interests.

Moving forward, we will continue to build on lessons learned, test findings and assumptions from the pilot project, collaboratively implement and improve the HSE program with families and Head Start staff members, and use the program to advance the field’s understanding of how STEM-related interests develop at this early age. The next several years will also be a chance for the team to deepen the extent to which the community drives the project. For example, we are currently organizing a parent advisory group, modeled after the MHCC Head Start Parent Council that oversees all of the organization’s major program decisions. The group will include volunteer parents from each HSE implementation site and will meet regularly with the team to guide programming for long-term sustainability. Ongoing program implementation and testing will also allow us to understand whether the experiences of the pilot families are representative of the broader Head Start population.

This work will set the stage for broader implementation of the program across the region, rigorous outcome assessment for families beginning when they enter Head Start and extending through kindergarten, and ongoing studies of family interest development during these years. Ultimately, our goal is to develop a sustainable, community-based partnership of educators, researchers, and families that engages in ongoing cycles of program testing and improvement that lead to deep, long-lasting impacts in the community, as well as important insights for the field about early childhood STEM education.

Through our experience with the HSE program, we believe that to truly support families from low-income backgrounds, educators must consider the broader context of these families’ lives and the many forces that shape how they are able to support their children’s learning and development. All of the parents we work with are strongly committed to their families and the future of their children. Because they live in poverty, however, they often face challenges that are hard for us as STEM educators to imagine, including hunger, housing insecurity, and multiple jobs. By partnering with Head Start, we are helping ensure that parents have the support and resources they need to engage with engineering and facilitate their children’s learning. We encourage other educators in the field to consider what partnerships and collaborations could provide this holistic support for local families. It is only through this systemic approach, we believe, that we as STEM educators can truly begin to address the persistent barriers to lifelong STEM learning for all.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by NSF grant DRL-1515628.

Scott Pattison (scott.pattison@freechoicelearning.org) is director of research at the Institute for Learning Innovation in Portland, Oregon. Gina Svarovsky (gsvarovsky@nd.edu) is assistant professor of practice at the University of Notre Dame Center for STEM Education in South Bend, Indiana. Ivel Gontan (ivel.gontan@gmail.com) is community program senior manager at the Fleet Science Center in San Diego, California. Pam Greenough Corrie (pam.corrie@mhcc.edu) is director of the Mt. Hood Community College Head Start Program near Gresham, Oregon. Marcie Benne (mbenne@omsi.edu) is director of engagement research and advancement at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, Oregon. Shannon Weissis (sweiss@omsi.edu) research and evaluation strategist at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, Oregon. Verónika Nuñez (vnunez@omsi.edu) is senior community engagement and learning engagement specialist at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, Oregon. Smirla Ramos-Montañez (sramos-montanez@omsi.edu) is research and evaluation associate at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, Oregon.

Engineering STEM Informal Education