Interdisciplinary Ideas

Integrating nonfiction chapter books into a science unit

Integrating nonfiction chapter books into a science unit

By KATIE COPPENS

Bringing other subjects into the classroom

For years, science textbooks and science-related websites were the primary sources of nonfiction reading in my classroom. However, science-themed nonfiction trade books can also serve as an engaging class resource that embed the (NGAC and CCSSO) expectations for literacy. In the process of reading these books, students will improve their reading skills and gain scientific knowledge.

According to Mazhoon-Hagheghi et al. (2018), nonfiction trade books allow teachers to introduce a variety of science concepts into their classroom, with the added benefit of including new contexts and cultures. The authors also emphasize that trade books allow science teachers to foster literacy learning while meeting the needs of individual students.

The integration of nonfiction trade books can be seen in an ecology unit that I teach to sixth graders. Throughout the last month of this three-month unit, students read a nonfiction book that connects to ecology. Students select a book, examine the text structure, and learn how to take notes with a targeted purpose. The notes are used on the end-of-unit summative assessment, for which students write a five-paragraph essay. This essay has a claim of the overarching concept of the unit, which is “All living things depend on the conditions of their environment.” The purpose of the essay was to defend the claim with science-based evidence. The content of the book serves as one of the three supporting paragraphs of evidence that defend the essay’s claim. The other supporting paragraphs are based on topics that students learned throughout the ecology unit.

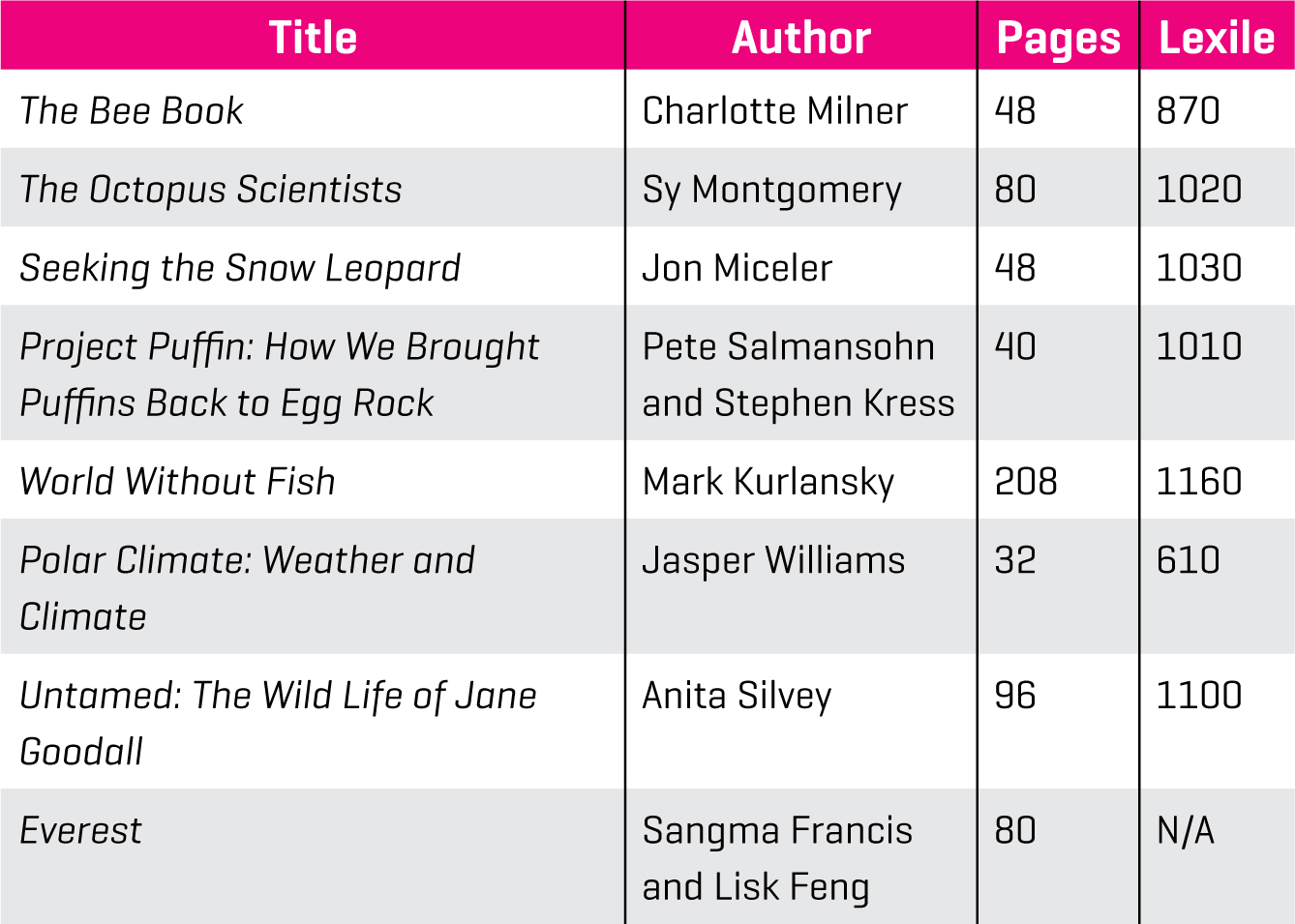

I have multiple copies of eight different books (Figure 1) for students to choose from, purchased by my school district and through a grant from our parent–teacher organization. Using NSTA’s Outstanding Science Trade Books list (see Resources) or talking to your school’s librarian can be a great way to generate a list of books. To aid with differentiation, we purchased books that had a range of text structures, lengths, and Lexile levels. Lexile levels are based on the complexity of a text’s sentence structure and vocabulary. Having options such as The Bee Book, which uses colorful drawings to show information and vocabulary, was an important option for English language learners. (A useful website to find the Lexile for books is www.lexile.com; also see Resources.)

Students have one class period to look over the eight books and make their selection. Students also have time to start reading in class that same day, so they can confirm that the book is well-suited for their abilities and interests. Students use Boushey and Moser’s (2006) I PICK acronym to make this decision. “I” stands for “I choose a book.” In this case, students start by choosing a book from the selection of books provided or going to the library to choose an ecology-based book. “P” stands for “purpose”; students confirm that they understand the purpose of reading. In this unit, the book’s content was connected to the overarching concept of the ecology unit. “I” represents “interest”; students survey the text to determine whether the topic is interesting to them. “C” stands for “comprehend”; this involves students reading the first few pages and asking themselves comprehension questions such as, “Do I understand what I just read?” This goes with the “K,” or “know,” which represents students asking themselves, “Do I know most of the words?” If a student struggles with the vocabulary, it can serve as a sign that the book is not the right fit for independent reading.

Because students read the books at school and at home, once a selection was made, each book was labeled with a number and assigned to a student. A sticky note was also taped to the front of the book with the teacher and student’s name. This helped prevent books from being misplaced or mixed up with other students who were reading the same book.

During the following class, seats were rearranged so that students reading the same book sat together. A benefit of students sitting near others reading the same book is that students would often talk with their neighbor about the content of the book. This also allowed students the opportunity to discuss the books and collaborate on skills such as how to approach note-taking. At the start of this class, students first examined their books’ text structure. Text structure is an author’s approach to organizing information. There are thought to be five common nonfiction text structures: description, cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution, and sequence (Meyer 1985). Students were familiar with how to examine nonfiction text structure independently because throughout the year, before reading any text, they had learned to preview and identify the author’s organizational method (Coppens 2019). Conferring with their neighbors who were reading the same book, students discussed the book’s text structure and how examining a book’s structure can be helpful as an approach to taking notes. Depending on the text structure, some students took notes on the chronological events of the story, whereas others structured their notes in terms of the problem and the solution or the cause and the effect. Students could choose their preferred method for note-taking; half of the class took notes in Google Docs, a quarter with sticky notes in the book, and a quarter took notes with paper and pencil. A benefit of computer-generated notes is that they could not be lost and could easily be edited. For some, the computer added an extra step of typing, so they preferred to use pencil and paper. Others liked the visual aspect of sticky notes. Students shared their note-taking methods with the class and some projected their digital notes through the classroom’s Apple TV to create a collaborative environment around this assignment.

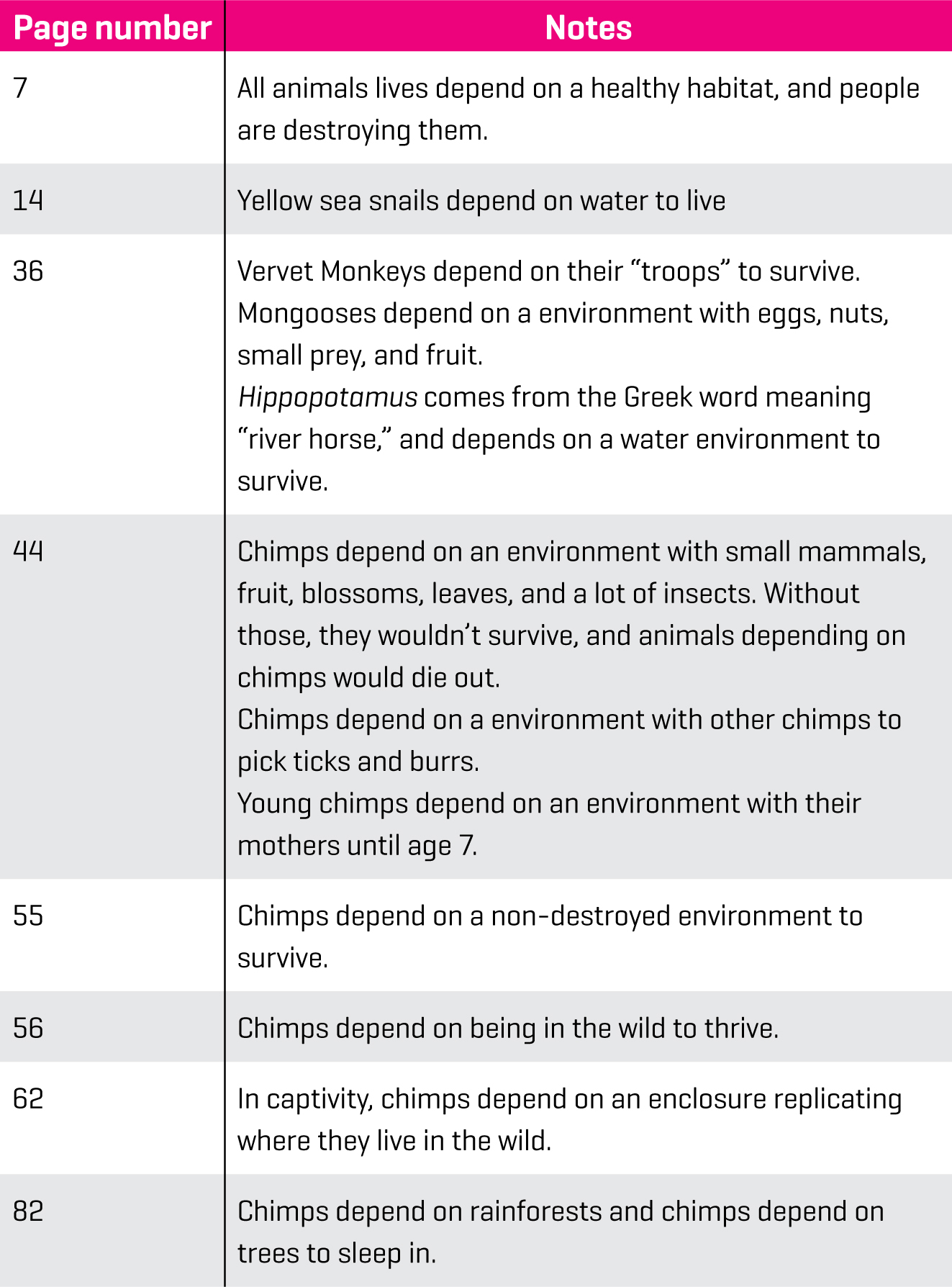

Figure 2 shows an example of how one student organized the information sequentially by using two-column notes. The two-column note-taking method is an approach that can easily be adapted to any nonfiction book. The left-hand column often has main ideas, questions, vocabulary terms, or page numbers, and the right-hand column has more detailed information. The student in Figure 2 also wrote “All living things depend on the conditions of their environment” at the top of her notes to serve as a reminder that everything should connect to this concept. After the student in Figure 2 shared her idea of having the overarching statement on the top of her note-taking sheet, another student shared with the class the idea of writing it on a bookmark to focus her reading and note-taking.

Using text structure to create a note-taking method worked well for my students, but what they needed the most support with was how to prioritize the information. A useful strategy when reading was to ask the following questions: “What’s important?” and “What’s really, really important?” We said notes should only be taken on facts and examples that could be used as evidence for the essay’s claim of “All living things depend on the conditions of their environment.” To model note-taking with this focus, I used Project Puffin: How We Brought Puffins Back to Egg Rock, which is the story of a landmark approach of transplanting young Atlantic puffins to a region of Maine where they once lived. The book tells the story of how decoys, mirrors, and birdcalls were used to lure the transplanted puffins back after their migration. This method helped establish an ongoing puffin population on the island and is now a restoration approach used worldwide (Salmansohn and Kress 2003). I explained to students that it is not necessary to take notes on things such as the physical features of puffins, but to instead focus on what conditions caused puffins to be an endangered species and what conditions helped in their return to Maine.

Over the month of reading their chosen book, students were given benchmarks of completing 25% of the book by the end of week 1, 50% of the book by the end of week 2, 75% by the end of week 3, and all of the book by the end of week 4. Before reading, students marked these benchmarks in their book with sticky notes, with flexibility in terms of ending on a chapter rather than midchapter. If students wanted to read ahead, they were encouraged to do so. The benchmarks were primarily in place to create pacing for those who may get behind.

Before completing the on-demand essay, for which students had one 50-minute class period to write, students were given one full class to prepare for the essay. As a class, we filled out a graphic organizer by brainstorming concepts that they learned over the unit. Students knew paragraph 1 would be introducing the claim that “All living things depend on the conditions of their environment” and that paragraph 2 would be using the book’s content to serve as evidence of this claim. Paragraphs 3 and 4 would be topics of choice from concepts learned in the ecology unit. Students used this organizer to prioritize what facts and information they would use in their essay.

During the next class, the organizer was the only resource students had in front of them when handwriting or typing their on-demand essay. Students were scored using our district’s ecology standard and standard for using evidence-based explanations (see Online Supplemental Materials for a rubric). Out of each of the paragraphs in the essay, the majority of my students said the paragraph on the book’s content was the easiest to write because reading the book and taking notes caused them to have strong comprehension of the topic.

With only a few combined days of class time being taken for the addition of these books to the unit, many important literacy skills were applied and numerous benefits gained. Nonfiction trade books allow students to apply their nonfiction reading and writing skills, better understand the overarching concept of our science unit, and learn more about a topic they are interested in.