Elementary | Formative Assessment Probe

Is It a Plant?

By Page Keeley

Assessment Life Science Elementary Grade 1

Sensemaking Checklist

This is the new updated edition of the first book in the bestselling Uncovering Student Ideas in Science series. Like the first edition of volume 1, this book helps pinpoint what your students know (or think they know) so you can monitor their learning and adjust your teaching accordingly. Loaded with classroom-friendly features you can use immediately, the book includes 25 “probes”—brief, easily administered formative assessments designed to understand your students’ thinking about 60 core science concepts.

Purpose

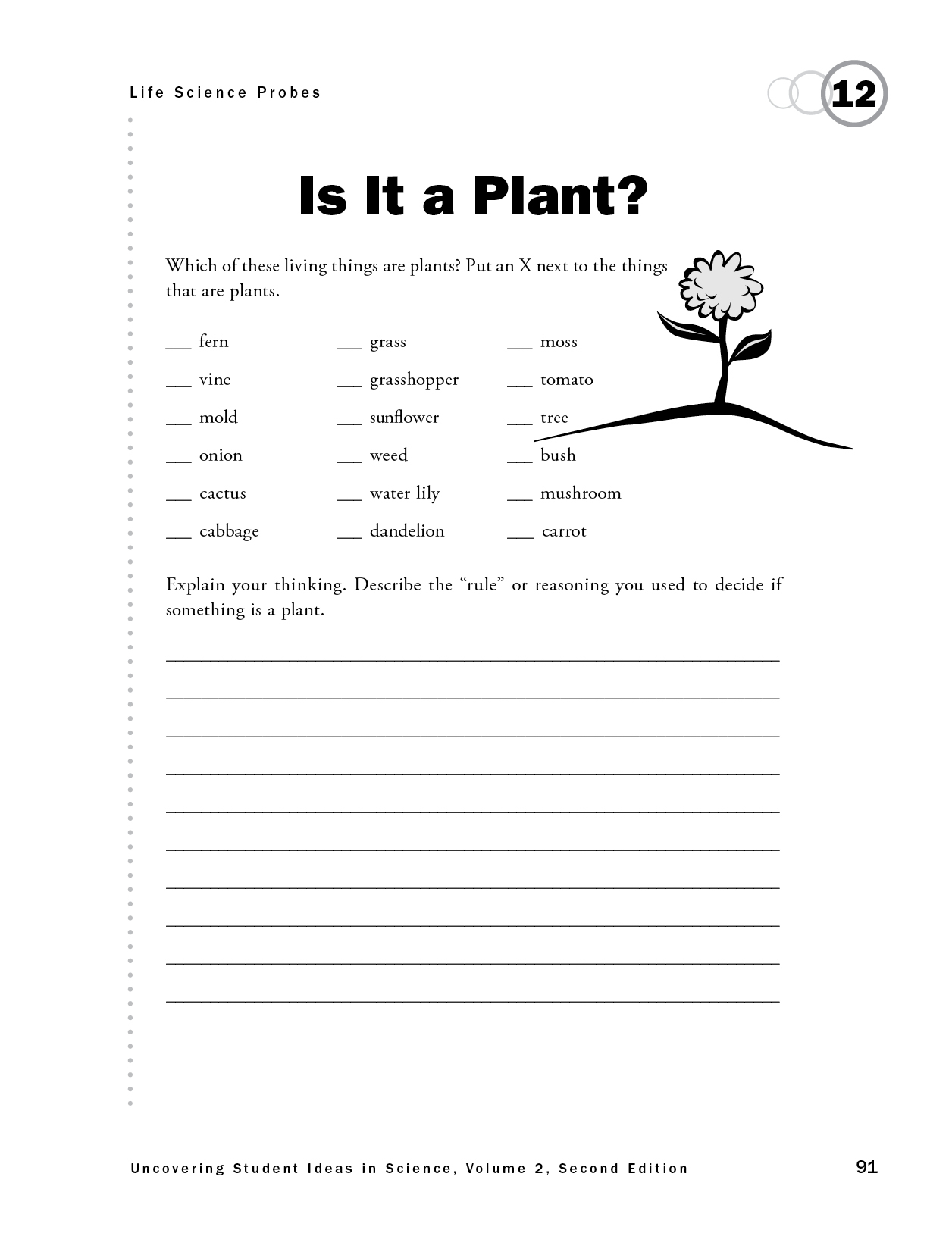

The purpose of this assessment probe is to elicit students’ ideas about the concept of a plant. The probe is designed to find out how students determine whether a living thing is considered to be a plant.

Type of Probe

Justified list

Related Concepts

Plant, fungi, biological classification

Explanation

The items on the list biologically considered to be plants are fern, grass, moss, vine, tomato, sunflower, tree, onion, weed, bush, cactus, cabbage, dandelion, water lily, and carrot. Plants are multicellular organisms that make their own food through photosynthesis. Many plant cells contain pigments capable of absorbing light. Plants have a structure called a cell wall, which is made mostly of cellulose. Plants can vary in size (from tall trees to short mosses), live on land or in water, and may be flowering or nonflowering.

Some of the items on this list are “plantlike” but are not plants. For example, mushrooms and mold are classified as fungi. Their cell walls are generally made of chitin instead of cellulose, and they do not make their own food or contain light-absorbing pigments within their cells. Just because something is green does not mean it is a plant. The grasshopper is a green animal.

Curricular and Instructional Considerations

Elementary Students

Plants are a common organism for investigation into the characteristics of and processes that support life. Typically, young students learn to distinguish plants from other organisms by their structures, unique needs (such as light), observable functions, and outward appearance (green). Characteristics used for grouping plants or distinguishing plants from other organisms are based primarily on observations of external structures and characteristics. Details about their cell structures, photosynthesis, embryological development, and modern taxonomy exceed learning expectations for classifying plants at this level.

Although students may have opportunities to observe and investigate plants and plant parts, their conception of a plant may be limited to the types of plants they have had experiences with—typically, flowering plants. Students may fail to develop a generalization of what a plant is if they are limited in experience to one type of plant. This probe is useful in determining whether students recognize that plants are a broad category for a variety of biologically diverse organisms.

Middle School Students

Current standards deemphasize biological classification schemes. However, students should be able to distinguish between major kingdoms or domains. They distinguish plants from other plantlike organisms, including fungi and green algae. They examine different types of cells with simple microscopes and can distinguish plant cells from animal cells by their observable structures. Middle school students are familiar with plant cell structures, such as cell walls and chloroplasts, but do not need to know the structural components of these organelles. Students recognize the ability of plants to make their own food through photosynthesis and the role of plants as producers in ecosystems.

High School Students

At the high school level, students use modern taxonomic criteria to distinguish among and between organisms. They can begin to use more sophisticated criteria to define plants, including embryological development, structures such as plastids, autotrophism, and molecular substances found in plant structures such as chlorophyll. However, caution must be used with the extensive terminology students typically encounter in biology. Although they may “learn” these terms and criteria, they may still revert to their earlier concept of a plant.

Administering the Probe

This probe is best used with grade 3–8 students. Be sure students understand that the living things on the list refer to the complete organism. For example, tomato refers to the complete tomato plant, not just the fruit. Make sure students are familiar with the items on the list; you may wish to remove or replace items that students have little or no familiarity with. High school teachers may add additional items such as algae, yeast, orchids, lichens, slime molds, euglena, and Venus flytraps.

Related Research

- Elementary students hold a more restricted meaning of the word plant than biologists. Trees, vegetables, and grass are often not considered to be plants. Methods of grouping organisms vary by developmental level. For example, in upper elementary school, some students may group organisms such as plants by observable features, whereas others base their groupings on concepts. By middle school, students start to group organisms hierarchically when they are asked to do so. It is not until high school that students use hierarchical taxonomies without being prompted (AAAS 2009).

- A study conducted by Barman et al. (2001) found that the characteristics elementary and middle school students strongly identified with plants were that plants have stems and leaves, are green, and grow in soil. Students frequently identified a flower, fern, and bush as being a plant. They were less sure about grass, oak tree, pine tree, and Venus flytrap.

- McNair and Stein (2001) found that when children and adults were asked to draw a plant, most drew a flowering plant.

- “Plant” is a familiar concept from everyday life, yet research suggests many school-age students struggle to define and apply the term according to the accepted scientific definitions (Driver et al. 1994).

- In a study by Leach et al. (1992), students used plant, tree, and flower as mutually exclusive groups. However, when students were given a restricted number of classification categories in a classification task, they assigned trees and flowers to the plant category. Leach and his colleagues also found that students are more apt to rely on macroscopic features rather than cellular or physiological characteristics.

- In a study by Stead (1980), some children suggested that a plant is something that is cultivated; hence, grass and dandelions were considered weeds, not plants. Some children considered cabbage and carrots to be vegetables, not plants. They viewed vegetables as a comparable set, rather than a subset, of plants.

- Ryman’s early research (1974) found that 12-year-old English students had more difficulty classifying plants into taxonomic categories than they did classifying animals. It appeared that students learned a “school science” way of classifying but retained their intuitive ideas about plant classification in everyday life. Ryman also found that students were likely to identify something as being a plant if it had plantlike structures, such as the stalk of a mushroom.

Related NSTA Resources

Barman, C., M. Stein, N. Barman, and S. McNair. 2002. Assessing students’ ideas about plants. Science and Children 40 (1): 46–51.

Franklin, K. 2001. Bring classification to life. Science Scope 25 (3): 36–41.

Keeley, P. 2017. Formative assessment probes: Uncovering young children’s concept of a plant. Science and Children 55 (2): 20–22.

Lawniczak, S., T. Gerber, and J. Beck. 1994. Plants on display. Science and Children 41 (9): 24–29.

Texley, J. 2002. Teaching the new taxonomy: Getting up to speed on recent developments in taxonomy. The Science Teacher 69 (3): 62–66.

Suggestions for Instruction and Assessment

- A similar version of this probe is available for grade K–2 students in Uncovering Student Ideas in Primary Science, Volume 1 (Keeley 2013).

- This probe addresses the concept of a plant. It is important to know whether students have a biological concept of a plant before expecting them to use disciplinary core ideas about plants.

- This probe can be used as a card sort. In small groups, students can sort cards with the names of organisms into two groups— “plants” and “not plants.” Listening carefully to students as they discuss and argue about which category the organisms on the list belongs to lends additional insight into student thinking. An alternative sorting method is to use pictures of plants with or without names, including plants in natural settings, gardens, and pots. Pictures can also be combined with real examples of plants on the list. With younger elementary students, sorting can be done as a wholeclass group activity with discussion.

- Provide opportunities for students to observe, identify, and investigate a variety of flowering and nonflowering plants, not just the typical flowering plants (e.g., bean plants) that are commonly used in classroom investigations. Students should observe varieties such as vegetable-yielding plants, flowering plants, aquatic plants, ferns, mosses, trees, vines, weeds, bushes, and grasses.

- Alert students to the common use of the word plant versus the scientific use of the word so that students will recognize trees, weeds, vines, cacti, and other plants that are referred to by names that do not include the word plant as also belonging to a larger group called plants. We don’t call a maple tree a maple plant, but it is still a plant. • Use concept mapping to have students visually describe the concept of a plant and connect it to other concepts.

- Draw comparisons between familiar subsets of animal classifications (e.g., reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds, and mammals grouped under vertebrates, which are grouped under animals) and subsets of plant classifications so that students can develop the idea of “plant” as a broad category that includes a variety of subsets with common characteristics. For example, there are vascular plants and nonvascular plants. Vascular plants can be broken down into subsets that include plants that do not produce seeds and those that produce seeds. Seed-producing plants can be further broken down into subsets of flowering seed plants and nonflowering seed plants. This will help older students understand that plants include a variety of groupings.

- Some students use the color green as a criterion for a plant. Challenge students to come up with plants that are not green and research the function of the pigments. For example, does a red-leaf tree still produce chlorophyll for photosynthesis?

- Have students turn to text, using the science practice of obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information, to explain why some of the organisms on the list, such as trees, are considered plants. For example, the young readers book A Tree Is a Plant explains that a tree is a large plant (Bulla 2001).