Elementary | Formative Assessment Probe

Standing On One Foot

By Page Keeley

Assessment Physical Science Elementary Grade 5

Sensemaking Checklist

This is the new updated edition of the first book in the bestselling Uncovering Student Ideas in Science series. Like the first edition of volume 1, this book helps pinpoint what your students know (or think they know) so you can monitor their learning and adjust your teaching accordingly. Loaded with classroom-friendly features you can use immediately, the book includes 25 “probes”—brief, easily administered formative assessments designed to understand your students’ thinking about 60 core science concepts.

Purpose

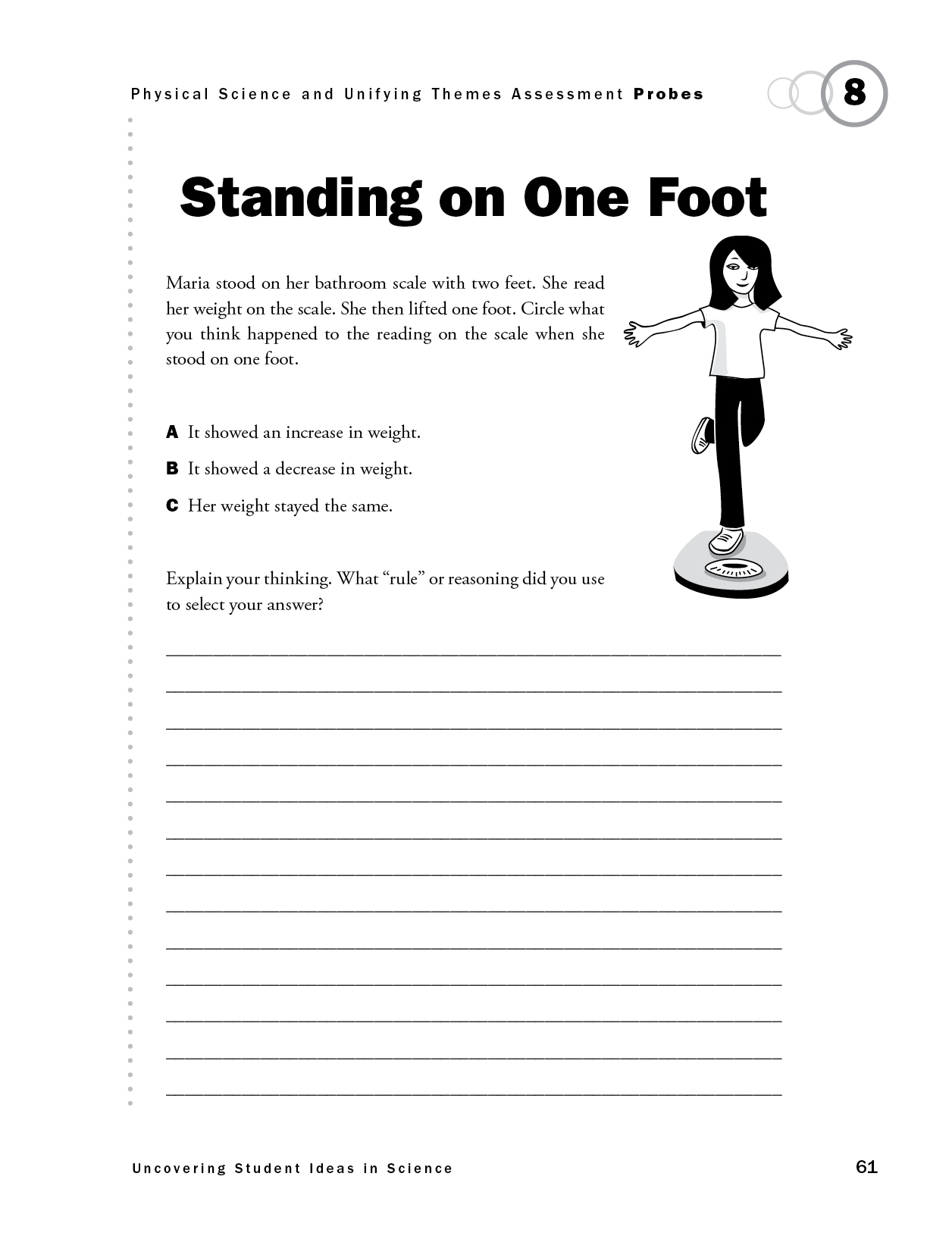

The purpose of this assessment probe is to elicit students’ ideas about weight and pressure. The probe is designed to determine whether students think their weight changes when the force exerted per unit area (pressure) on a scale changes.

Type of Probe

More A-More B

Related Concepts

force, gravity, pressure, weight

Explanation

The best answer is C: Her weight stayed the same. Weight is the force of gravity acting on an object. Regardless of whether you stand on two feet or one foot, the force of gravity acting on your body as you stand on a bathroom scale is the same. When you stand on two feet, the force is distributed over a wider area (the total area covered by the two soles of your feet). When you lift one foot, the same force is distributed over a smaller area (the area covered by the sole of one of your feet). Pressure changes as the constant weight of the body is distributed over different areas. Because pressure is described as force per unit area (P = F ÷ A), as the area covered by the body on the scale decreases by lifting one foot, the pressure increases. Although the pressure increases, the weight remains constant.

Curricular and Instructional Considerations

Elementary Students

In the elementary grades, students use simple instruments to gather data. They learn to measure weight and mass using various types of scales and pan balances. At this stage, weight is an observational property that they use to describe objects and materials. Elementary students are not expected to know that weight is caused by the force of gravity. However, they should be able to observe that the weight of an object stays the same in the same location on Earth.

Middle School Students

At the middle school level, students should begin to distinguish between weight and mass. They develop an understanding that the force of the Earth’s gravity affects the weight of an object. They often confuse pressure with weight. This is a time when their use of mathematics (area and proportionality) can be used to explain why their weight doesn’t change when different amounts of their body are in contact with the scale.

High School Students

In high school, students develop more sophisticated notions of weight, mass, and pressure. However, they may still revert to naive ideas about weight.

Administering the Probe

You can demonstrate the context for this probe by bringing in a bathroom scale, standing on it with two feet, then lifting one foot. Make sure students do not see the reading on the scale as you demonstrate.

Related Research

- The idea that the weight of an object is a force—the force of gravity on that object— does not appear to be a firmly held idea among secondary students (Driver et al. 1994).

- There is not a lot of research on students’ ability to distinguish between weight and pressure in relation to the surface area of an object in contact with a weighing instrument, such as a bathroom scale. Our field tests with elementary and middle school students showed that many students believed that the weight increases when there is less surface area touching the scale because “it presses down harder.” Some students also believed the weight would decrease because the amount of force pushing down is less when one foot is lifted. These ideas were less prevalent with high school students, although some students still believed standing on one foot would press down harder and increase the weight.

Related NSTA Resources

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). 2001. Atlas of science literacy. Vol. 1. (See “Gravity,” pp. 42–43.) Washington, DC: AAAS.

Nelson, G. 2004. What is gravity? Science & Children (Sept.): 22–23.

Robertson, W. 2002. Force and motion: Stop faking it! Finally understanding science so you can teach it. Arlington, VA: NSTA Press.

Suggestions for Instruction and Assessment

- This probe lends itself to an inquiry investigation. Have students commit to a prediction, explain their reasoning that supports their prediction and then test it. When students find their observation does not match their prediction, encourage them to discuss their ideas and seek information to support a new explanation.

- With younger children, have them weigh a variety of objects by placing them on their side, top, bottom, or in other configurations, observing how the weight stays the same. Be sure to place the object in the center of the weighing pan or device each time.

- Challenge students with other examples illustrating the difference between weight and pressure. For example, imagine that you had two different pairs of shoes that weighed the same. One was a pair of high spiked heels and the other was a pair with flat soles. When you put the high spiked heels on and stood on soft ground, the heel sunk down into the ground. When you put the flat sole on, you stayed on top of the ground. What changed, your weight or the shoes? Why did this change in the shoes affect how you stood on the soft ground?

- After developing an operational definition of pressure, have students compare the pressure exerted by one foot on the scale with two feet on the scale. Have students trace their feet on square grid paper and count up the number of square units covered by one versus two feet. Calculate the pressure by dividing their weight by the square units.