Students’ Self-Assessment and Reflection

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2017-07-31

Do you have ideas on how to help my middle school students become more thoughtful, independent learners? —J., Michigan

Do you have ideas on how to help my middle school students become more thoughtful, independent learners? —J., Michigan

In my experience, self-assessment and reflective activities gave students ownership in their learning.

Self-assessment is more than students “correcting” their own papers. When students self-assess, they reflect on the results of their efforts and their progress toward meeting the learning goals or performance expectations. They examine their work for evidence of quality and decide what to do next.

But if you ask middle school students to “reflect,” you may get puzzled looks or blank stares. Students don’t necessarily have this skill. They may initially think that an assignment or project is good simply because they spent a lot of time on it, they enjoyed it, or they worked very hard on it.

Students may need to be taught strategies for self-assessment through examples and practice. Take a piece of student work (with no name on it) and guide students through the process of comparing the work to the rubric. You may have to do this several times before students feel comfortable critiquing their own work.

Share with students how they could reflect on their own learning with responses to prompts such as: I learned that… I learned how to… I need to learn more about… It’s very powerful if you share your responses to your own work. , too.

In their notebooks, students could reflect on their work with prompts such as From doing this project I learned… To make this project better, I could…or Our study team could have improved our work by…

Honest self-assessment and reflection are difficult processes, even for adults. But they are valuable tools for developing lifelong learners.

Ed News: The Next Generation Science Standards’ Next Big Challenge

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2017-07-28

This week in education news, NGSS’ next big challenge…finding curricula; Girl Scouts 23 new STEM badges; school success stops and ends with teachers; new report finds science teachers are often expected to teach beyond their subject matter training; New York school district to send science experiment to space; Trump Administration ask Tech CEOs for STEM policy advice; President Trump donates his second-quarter salary to education department; schools need to do more to equip K-12 students with computational thinking skills; Colorado adopts STEM seals for high school diplomas; and Alabama Governor Kay Ivey unveiled a new education initiative.

The Next Generation Science Standards’ Next Big Challenge: Finding Curricula

As states wrestle with putting the Next Generation Science Standards into action, one question I’m hearing more and more: What to do about curriculum? It’s also a question that’s been on the mind of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, which provided major support to the groups that developed the framework and standards that evolved into the NGSS. Click here to read the article featured in Education Week.

Together, Technology And Teachers Can Revamp Schools

In 1953 B.F. Skinner built his first “teaching machine”, which let children tackle questions at their own pace. By the mid-1960s similar gizmos were being flogged by door-to-door salesmen. Within a few years, though, enthusiasm for them had fizzled out. Since then education technology (edtech) has repeated the cycle of hype and flop, even as computers have reshaped almost every other part of life. One reason is the conservatism of teachers and their unions. But another is that the brain-stretching potential of edtech has remained unproven. Click here to read the article featured in The Economist.

Girl Scouts Adds 23 New Badges To Encourage Girls In Science, Tech

Girl Scouts can now earn badges in designing robots and coding in addition to legacy badges of first-aid and hiking. Is there anything these girls can’t do? The Girl Scouts of the USA announced Tuesday the addition of 23 new badges in the Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) fields. The move marks the largest programming rollout in almost a decade. Click here to read the article featured in USA Today.

Trump Budget Endangers STEM Learning

Any observant educator knows that after-school and summer learning opportunities are critical elements of a great education, helping students to succeed in school, work, and life. President Donald Trump’s proposed federal budget for fiscal 2018 would eliminate the single largest funding source for these programs: an annual $1.2 billion for after-school programs supported by the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program, which enrolls more than 1 million students across rural, urban, and suburban communities in all 50 states. But the damage wouldn’t stop there. Click here to read the article featured in Education Week.

District Chief: Why School Success Stops And Ends With Teachers

I believe the hardest day of any job is the very first day. On that first day, the basic, most elementary parts of the workplace are foreign. Where do I park? Where is the coffee? How do I log in to my new computer? The list of things to learn goes on and on. However, a new job also brings tremendous opportunity. Click here to read the article featured in eSchool News.

Study Shows Science Teachers Often Teach Beyond Their Training

A new study from researchers at Brigham Young University and the University of Georgia shows that new science teachers are often expected to teach beyond their subject matter training. College students training to be middle or high school science teachers, often choose a subject, like biology, chemistry or physics. They then take the necessary classes to specialize in that subject area so they can achieve a “highly qualified” teacher status. But, the majority of new science teachers across the country, 64 percent, are asked to teach more than their area of expertise. Click here to listen to the segment on KUER-FM.

Prepping Students For Future Computer Science Jobs

The economy is rapidly feeling the impact of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, which allows computers to make decisions, recognize speech and perform other traditionally “human” tasks. Nearly half of all jobs in the U.S. in the next 10 to 20 years will be related to AI, according to a 2016 Obama administration report, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and the Economy.” But the quality of computer science education varies widely across the country. Click here to read the article featured in District Administration.

Rochester City School District To Send Science Experiment To Space

Rochester, New York, students have some bragging rights when it comes to space exploration. East High School students in the Rochester City School District recently earned the opportunity to send their microgravity experiment to the International Space Station. The experiment—which tests the role of microgravity in the production of chlorophyll—is one of 21 student projects that will launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida this month. Click here to read the article featured in District Administration.

Trump Administration Tapping Tech CEOs For STEM Policy Approach

White House officials including Ivanka Trump have begun an outreach campaign to major technology, business and education leaders including Laurene Powell Jobs and Apple’s Tim Cook for advice on shaping funding approaches to science, technology, engineering and math education in U.S. public schools. Click here to read the article featured on Bloomberg.com

The Next Big Thing in Education Reform May Be Practice, Not Policy

The era of hyperactive education policymaking is about to come to an end. That might be hard to believe, given this summer’s high-decibel policy disputes, both in Washington and in the states. The implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA); debates about a potential large-scale federal school-choice initiative; and deep disagreements about civil rights enforcement continue to captivate—and roil—all of us involved in education policy, in D.C. and around the nation. Click here to read the article featured in Education Next.

Trump Donates $100,000 — His Second-Quarter Salary — To Education Department For Science Camp

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced at the White House on Wednesday that President Trump was donating $100,000, his salary for the second quarter of the year, to the Education Department to help fund a science camp. Click here to read the article featured in The Washington Post.

Congressional Panel Asks: What K-12 Skills Are Needed For STEM Workforce?

Schools need to do more to equip K-12 students with computational thinking skills to prepare them to fill the growing number of middle- and high-skilled jobs that require computing or programming skills, witnesses told members of a congressional committee this week. The STEM workforce is rapidly changing, said James Brown, the executive director of the STEM Education Coalition, a STEM education advocacy group. Click here to read the article featured in Education Week.

From Skyhook To STEM: Kareem Abdul Jabbar Brings The Science

Kareem Abdul Jabbar is taking his shot helping narrow the opportunity and equity gaps with his Skyhook Foundation and Camp Skyhook. The Los Angeles nonprofit helps public school students in the city access a free, fun, week-long STEM education camp experience in the Angeles National Forest. Click here to listen to the segment featured on NPR.

State Adopt STEM Seals For High School Diplomas

Colorado educators Elaine Menardi and Jess Buller would seem an unlikely pair to be writing legislation. But neither felt that their students, then middle schoolers, were on track for meeting state benchmarks for workforce readiness in technology and computing. So, while participating in a fellowship together, the two cooked up a solution: a STEM diploma endorsement awarded to high school students with a track record of strong achievement in those subjects. Click here to read the article featured in Education Week.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey Unveils First Big Issue Important To Her: Education

Gov. Kay Ivey unveiled a new education initiative on Wednesday, focusing on three stages of education: early childhood, computer science in middle and high school, and post-high school workforce preparedness. Calling this her first formal initiative as Governor of Alabama, Ivey said “Strong Start, Strong Finish” calls for various existing education groups to work together in a collaborative way from pre-kindergarten through workforce development. Click here to read the article featured on Al.com.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Legislative Update

Secretary DeVos and Ivanka Trump Team Up for STEM Ed

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2017-07-27

On Tuesday, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and Adviser to the President Ivanka Trump teamed up for a STEM-related reading event at the National Museum of American History and later worked on some STEM-focused projects with the students. Read more here.

The following day, President Trump donated his second quarter salary to the Department of Education to help fund a STEM-focused camp for students. The donation, totaling $100,000, was accepted by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos at the daily White House Press briefing, more here.

STEM Education Focus of Congressional Hearing

On Wednesday July 26, STEM Education Coalition Executive Director James Brown testified before the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology Subcommittee on Research and Technology at their hearing on “STEM and Computer Science Education: Preparing the 21st Century Workforce.”

The hearing focused on the importance of STEM and computer science education to meeting a wide range of critical current and future workforce needs. In his written testimony, Brown covered three key issues: how states are incorporating STEM as they work to implement the Every Students Succeeds Act; the changing nature of STEM careers; and the emergence of informal STEM education. View the hearing and read the testimony here, and learn more about the STEM Education Coalition here. (NSTA chairs the STEM Education Coalition.)

James Brown, Executive Director, STEM Education Coalition; Pat Yongpradit, Chief Academic Officer, Code.org; Representative Barbara Comstock (R-VA), Chair of the Research and Technology Subcommittee; A. Paul Alivisatos, Executive Vice Chancellor & Provost, Vice Chancellor for Research, and Professor of Chemistry and Materials Science & Engineering, University of California, Berkeley; and Dee Mooney, Executive Director, Micron Technology Foundation at the July 26 hearing on STEM Education.

Making the Most of ESSA: Opportunities to Advance STEM Education

ESSA to support STEM education. The report, which can be found here, is similar to the Achieve report released a few weeks ago on STEM in ESSA, which found (among other things) that 10 out of 16 states are including science assessment as part of an academic achievement or proficiency indicator.

New Title IV Coalition Website Now Available

Check out the new Title IV-A Coalition website, a great resource for teachers and other education stakeholders. The website has a ton of resources and information on the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) flexible block grant program under Title IV Part A, which provides states and districts with funding for activities in three broad areas:

- Providing students with a well-rounded education (e.g., college and career counseling, STEM, music and arts, civics, IB/AP);

- Supporting safe and healthy students (e.g., comprehensive school mental health, drug and violence prevention, training on trauma-informed practices, health and physical education); and

- Supporting the effective use of technology (e.g., professional development, blended learning, and purchase of devices).

More Title IV resources are also at the NSTA website here.

Stay tuned, and watch for more updates in future issues of NSTA Express.

Jodi Peterson is the Assistant Executive Director of Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. Reach her via e-mail at jpeterson@nsta.org or via Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

On Tuesday, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and Adviser to the President Ivanka Trump teamed up for a STEM-related reading event at the National Museum of American History and later worked on some STEM-focused projects with the students. Read more here.

Total Solar Eclipse on Monday, August 21, 2017!

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2017-07-26

If you haven’t heard about what is known as the Great American Eclipse by now, it is not too late. This August 21, 2017 natural phenomena promises to be well worth “attending” or stepping outdoors for at least a few minutes approaching the moment when most of the Sun is covered by the Moon in your location. A partial solar eclipse can be seen by everyone in North America and parts of South America, Africa, and Europe so even if you are not within the path of totality you can still experience and view this solar eclipse. If you have children in your care at the time, they will always remember the day the teacher did not follow the Daily Routine but took them outside to experience a darkening of the sunlight in daytime. They will remember the break from the ordinary and your excitement if nothing else.

If you haven’t heard about what is known as the Great American Eclipse by now, it is not too late. This August 21, 2017 natural phenomena promises to be well worth “attending” or stepping outdoors for at least a few minutes approaching the moment when most of the Sun is covered by the Moon in your location. A partial solar eclipse can be seen by everyone in North America and parts of South America, Africa, and Europe so even if you are not within the path of totality you can still experience and view this solar eclipse. If you have children in your care at the time, they will always remember the day the teacher did not follow the Daily Routine but took them outside to experience a darkening of the sunlight in daytime. They will remember the break from the ordinary and your excitement if nothing else.

A note about safety:

Indirect viewing may be the best way for young children to view images of the Sun during the eclipse. See the simple instructions for pinhole viewing from the American Astronomical Society. When talking about the Sun, I always tell children that we don’t look right at it because it will damage our eyes. Some children may be tempted to test their ability to look at the Sun to show how they can withstand pain. I tell children that even if it doesn’t hurt right now, the light will damage some of the insides of our eyes, making it harder to see, especially when we are older, so DON’T DO IT. Some suggest having people face the ground to put on the glasses before looking up at the Sun, to have time to make sure the glasses are on securely. The NASA website says this about safe viewing with special glasses:

Eclipse viewing glasses and handheld solar viewers should meet all the following criteria:

• Have certification information with a designated ISO 12312-2 international standard

• Have the manufacturer’s name and address printed somewhere on the product

• Not be used if they are older than three years, or have scratched or wrinkled lenses

• Not use homemade filters or be substituted for with ordinary sunglasses — not even very dark ones — because they are not safe for looking directly at the Sun

Our partner the American Astronomical Society has verified that these five manufacturers are making eclipse glasses and handheld solar viewers that meet the ISO 12312-2 international standard for such products: American Paper Optics, Baader Planetarium (AstroSolar Silver/Gold film only), Rainbow Symphony, Thousand Oaks Optical, and TSE 17.

Here are government agency and organizations’ links to information that will guide you in viewing safely and understanding the science at developmentally appropriate levels.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 2017 Solar Eclipse website answers the questions, Who? What? Where? When? and How? and provides information on safety, science information about the players (Sun, Moon, Earth), and resources including downloadable maps, fact sheets and posters.

Search the National Science Teachers Association’s store for “eclipse” to find new (and older) resources about eclipses, including a free article, “Total Eclipse” by Dennis Schatz and Andrew Fraknoi in the March 2017 issue of Science Teacher. Their book, When The Sun Goes Dark, features a family re-creating eclipses in their living room and exploring safe ways to view a solar eclipse. A free viewing guide is available as part of these authors’ book on solar science for middle school, Solar Science: Exploring Sunspots, Seasons, Eclipses, and More.

American Astronomical Society has a useful glossary of eclipse related vocabulary among many other resources and information.

Astronomical Society of the Pacific also has information and resources.

Astronomical Society of the Pacific also has information and resources.

GreatAmericanEclipse.com, published by Michael Zeiler and Polly White, is a fun site for eclipse maps and science facts.

I’m planning on making a special day of it with my family since I won’t be in school. Thanks to all the scientific community for making it possible for everyone to learn how to view the 2017 solar eclipse!

If you haven’t heard about what is known as the Great American Eclipse by now, it is not too late. This August 21, 2017 natural phenomena promises to be well worth “attending” or stepping outdoors for at least a few minutes approaching the moment when most of the Sun is covered by the Moon in your location.

If you haven’t heard about what is known as the Great American Eclipse by now, it is not too late. This August 21, 2017 natural phenomena promises to be well worth “attending” or stepping outdoors for at least a few minutes approaching the moment when most of the Sun is covered by the Moon in your location.

How NGSS and CCSS for ELA/Literacy Address Argument

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-07-25

In the summer of 2015, I observed an elementary science teacher from an NGSS-adopted state who made a presentation to her cohort of close to 100 K–12 science teacher leaders and administrators from schools, districts, and the state. After presenting her instruction on a physical science unit with 2nd-grade students, she gave her students the following assignment: “Write your opinion on . . . (the science topic).”

As a science educator, I was struck by the presenter’s use of “opinion” in science instruction. In an effort to unpack my misgivings, I decided to take a quick look at what the new science standards had to say about “opinion” in relation to argument. First, I consulted the Framework (NRC 2012), which states, “[y]oung students can begin by constructing an argument” and “begin to distinguish evidence from opinion” (p. 73). For example, the performance expectation K-ESS2-2 in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) states: Construct an argument supported by evidence for how plants and animals (including humans) can change the environment to meet their needs.

I then turned my attention to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for ELA/literacy. To my surprise, I discovered that “evidence” is introduced for the first time and used only once in grade 3, while “claim” is introduced for the first time and used only once in grade 5. In addition, “reasons” is used throughout K–5 and “reasoning” is introduced for the first time in grade 6. Finally, in grades 6–12, “argument” is used along with evidence, claim, and reasons or reasoning. The CCSS Appendix A (NGA Center and CCSSO 2010), which provides the research base for the CCSS, states, “Although young children are not able to produce fully developed logical arguments . . . In grades K–5, the term ‘opinion’ is used to refer to this developing form of argument” (p. 23).

A key instructional shift in the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS involves making connections across subject areas, which more accurately represent the reality of teachers and students who are trying to make meaning of multiple subject areas that have traditionally been treated in silos. One disciplinary practice that is emphasized consistently across the CCSS for ELA/literacy and mathematics and the NGSS is argument. But to what extent do subject area educators have a common understanding of argument?

In preparing a recent research article for publication (Lee 2017), I attempted to address this question more systematically. As both the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS claim to be research-based, reviewers of the journal encouraged me to look into relevant literature in ELA/literacy and science education with the aim of identifying conceptual sources of convergences and discrepancies between these two sets of standards. Eventually, my analysis of the two bodies of research literature and the two sets of standards in ELA/literacy and science education focused on (1) what counts as argument (i.e., disciplinary norms) and (2) when children are capable of engaging in argument (i.e., developmental progressions). Key findings are summarized as follows:

- Although the CCSS for ELA/literacy include many purposes of arguments, including persuasive arguments, they emphasize logical arguments in relation to college and career readiness.

- The description of argument in science that appears in the CCSS for ELA/literacy is comparable to how the Framework (NRC 2012) and the NGSS describe argument.

- The two sets of standards and relevant bodies of literature in ELA/literacy and science education acknowledge that what counts as argument or evidence differs across disciplines, but none offer explicit guidance on what these differences entail.

- The two sets of standards and relevant bodies of literature in ELA/literacy and science education present differing perspectives on K-5 students’ ability to engage in argument, as described above.

I support the CCSS for ELA/literacy and the NGSS in their efforts to make connections across subject areas and to highlight synergy and shared responsibilities among subject area educators. While capitalizing on convergences, it is equally important to reconcile discrepancies between different sets of standards and between different bodies of research literature. As new content standards are being implemented, the education community should attend to discrepancies between and across subject areas and commit to addressing such discrepancies. As a point of departure, a convening of stakeholders to discuss and resolve the discrepancies involving argument is one possible step to take, which could lead to further research and policy initiatives.

With the adoption of the CCSS and the NGSS across states, the responsibility of implementing these new standards falls primarily on classroom teachers. They are faced with limited information about what counts as argument across ELA/literacy and science education. Furthermore, they must contend with discrepant information about when children are able to engage in argument. As the NGSS are aligned closely with the grade-by-grade standards in the CCSS, such discrepancies have practical implications for classroom instruction and assessment. I was relieved and delighted when two leaders involved in writing the CCSS for ELA/literacy deferred to “research in science indicating young children could form arguments” and suggested that “as states are revising standards, they should take into consideration new research that’s out there” (Zubrzycki, 2017). In a similar manner, teachers and school districts should expect K-5 students to engage in argument from evidence consistently across subject areas, including ELA/literacy.

References

Lee, O. 2017. Common Core State Standards for ELA/literacy and Next Generation Science Standards: Convergences and discrepancies using argument as an example. Educational Researcher, 46(2), 90-102.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). 2010. Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Appendix A: Research supporting key elements of the standards, glossary of key terms. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_A.pdf

National Research Council (NRC). 2012. A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Zubrzycki, J. 2017. In elementary school science, what’s at stake when we call an ‘argument’ an ‘opinion’? Education Week, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2017/04/science_standards_common_core.html

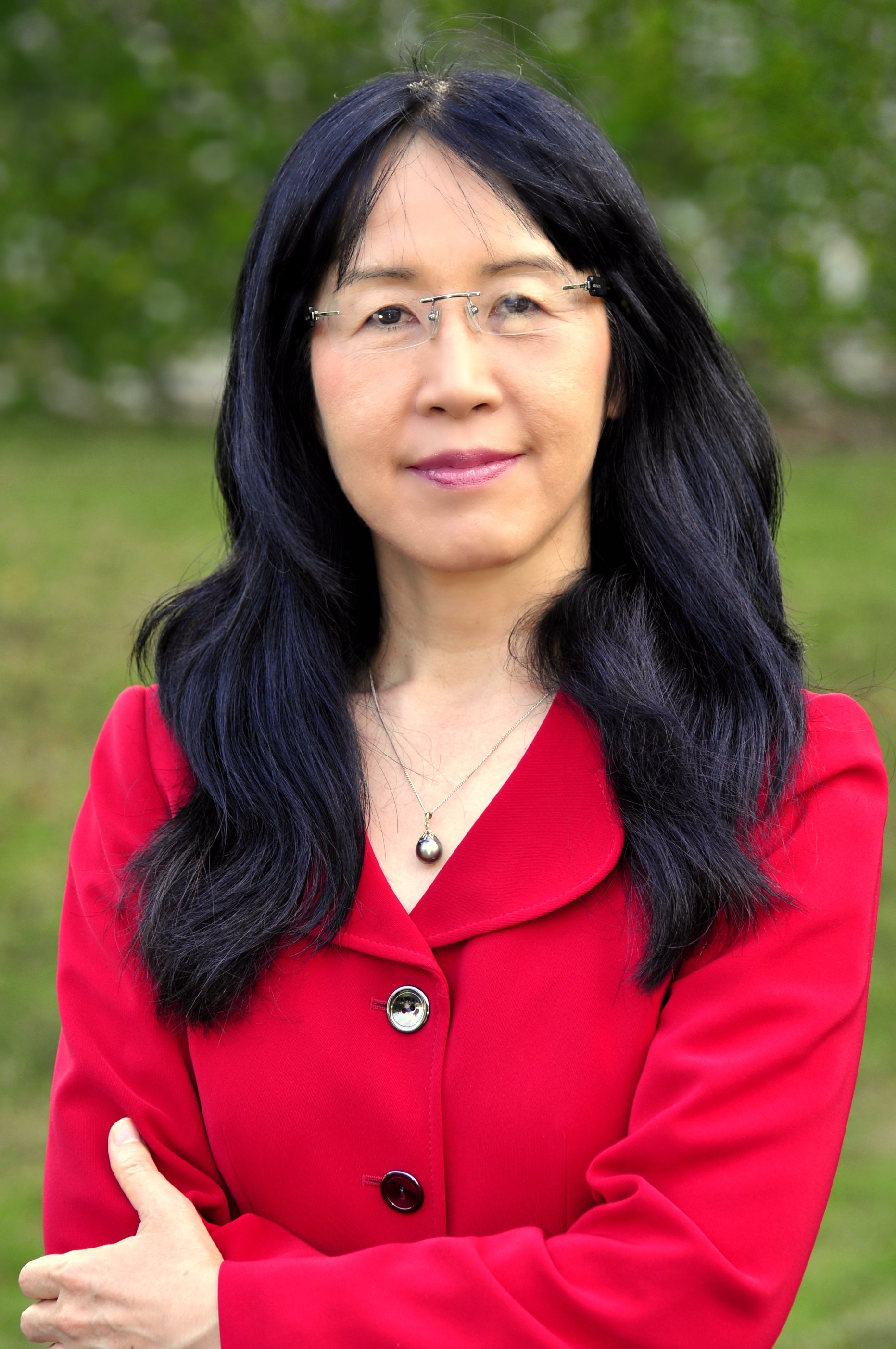

Okhee Lee

Okhee Lee is a professor in the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University. She was a member of the NGSS writing team and served as leader for the NGSS Diversity and Equity Team. She is currently developing NGSS-aligned instructional materials for students, especially English learners, in fifth grade.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

In the summer of 2015, I observed an elementary science teacher from an NGSS-adopted state who made a presentation to her cohort of close to 100 K–12 science teacher leaders and administrators from schools, districts, and the state. After presenting her instruction on a physical science unit with 2nd-grade students, she gave her students the following assignment: “Write your opinion on . . . (the science topic).”

Using Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning (CER) Strategy to Improve Student Learning

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-07-25

This past school year, I used claim, evidence, reasoning (CER) statements to show three-dimensional learning in my classroom. Several tools are available for doing this, but the one my students like is the CER Graphic Organizer and Transition Words List developed by Sandra Yellenberg.

My students like how this graphic organizer helped them organize their thoughts before writing their CER paragraphs. The first few times, we went through the process together to co-develop CER paragraphs. Sometimes we would develop a whole paragraph or a sentence to help explain a phenomenon. Co-developing the statements helped students feel more comfortable using the tool later on.

As students continued to use the tool, their statements gained complexity. Anytime students were asked to explain what they found out, they always used this tool and accompanying transition word bank. In several biology activities, we used the organizer to defend claims based on genetic analysis. In chemistry, we used the organizer to explain what the best way for organizing elements on the periodic table was. In physical science, we used a modified version of the organizer to develop correlations among kinetic and potential energy, speed, and friction using PhET’s Skate Park basics simulation. I also used the organizer in environmental science after having students do the activity Earth’s Dynamically Changing Climate, to explain how the eight pieces of evidence they examine help justify the claim that Earth’s climate is changing.

In the example below, students developed a claim to the question Who’s the Father?, an Inquiry-based Curriculum Enhancement activity by Indiana University. The paragraph the student team developed from their filled-in C-E-R Graphic Organizer follows:

In the case of who’s the father of Katie and David, we believe Mr. Ingram is the father. In the first place, Katie has four alleles matching with Mr. Ingram. She has only three alleles in common with Mr. Polacek. Coupled with David who has five alleles in common with Mr. Ingram and two alleles in common with Mr. Polacek. Also, Katie has three alleles in common with Mrs. Ingram. David has four alleles in common with Mrs. Ingram. Mr. and Mrs. Ingram are the parents of Katie and David because they have the most matching alleles.

In another biology example, students examined more complicated genetic analysis to determine who should get the inheritance. They had to develop a claim about who was the most likely candidate to be the daughter of Harold P. Smithson in another Inquiry-based Curriculum Enhancement activity by Indiana University. Students analyzed several different samples of loci with varying probabilities of matching for blood, as well as a hair sample. The paragraph a student team developed from their filled-in C-E-R Graphic Organizer appears below:

Candidate two is most likely the daughter (of) Harold P. Smithson. First we looked at the blood samples. Candidate two and four both have five matching alleles with Smithson. Candidate(s) one, three, and five only have two. Locus B has a low probability (of matching). For example, Locus B has a probability of 1/22,500. Even with this low probability (candidate) two matches twice. Also candidate two has at least one allele matching at every locus. Also we looked at a hair sample. Two has the most matching alleles with the hair sample, which was nine alleles. Candidate two has a total of 14 matching alleles with the blood and hair samples. In the final analysis candidate two is most likely the daughter.

Not only are students writing in science, focusing on the NGSS science and engineering practice of engaging in argument from evidence, but they are also using CCSS ELA writing standards, such as “Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” I found that after using the C-E-R Graphic Organizer to help students develop their paragraphs, their explanations were better developed and focused on using evidence to back up their claim.

Students needed more guidance in using transition words. They often repeated the same words to start their sentences and were unsure about which grouping of words to use with their evidence. I worked with students, through modeling, discussion, and individual check-ins, to help them determine which group of transition words to choose. In the future, giving students an abbreviated transition word list based on what type of question we are trying to answer should help alleviate some of the confusion with this piece. Students noted that the tool helped them develop paragraphs to prove a claim in other classes.

Since I work at a school-within-a-school, I was able to share the graphic organizer with the English teacher so we could use the same tool to help students develop arguments using evidence in English and science courses.

Nicole Vick

Nicole Vick is a high school science teacher in Galesburg, Illinois, and an NGSS@NSTA Curator. She has taught all content areas of science and holds degrees in biology and environmental science education. Vick is a Regional Director and serves as the Professional Development Leader for High School Earth and Space Science for the Illinois Science Teachers Association and as District XII Director for the National Science Teachers Association. She enjoys transitioning her classes to three-dimensional instruction and providing professional development to teachers throughout Illinois.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

This past school year, I used claim, evidence, reasoning (CER) statements to show three-dimensional learning in my classroom. Several tools are available for doing this, but the one my students like is the CER Graphic Organizer and Transition Words List developed by Sandra Yellenberg.

You Teach What? I’m So Sorry! Building a Better Body and Building Better Argumentation

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-07-25

I am always amazed at the looks on people’s faces when I tell them I teach middle school. They seem to pity me for having a position I chose and love! They inform me that middle school “tween-agers” are argumentative, stubborn, and at times, adamant about whatever they set their minds to. But I smile because I have the best job in the world!

The secret about my argumentative middle schoolers is that middle school is a prime time to teach students what argumentation really is and how it is used every day in decision-making processes. Middle schoolers make claims all the time, and if we can harness their passion to make statements, then we have implemented a very powerful tool indeed. When and how did I implement argumentation as an NGSS Science and Engineering Practice (SEP) in my classroom? I started slowly and used the progression of the SEPs to construct “articles of argumentation” to help guide our learning processes.

Article 1: Engage With Evidence, Embrace the Phenomena

The first unit I aligned with NGSS was formerly known as my Human Body unit. I struggled with how to teach body systems as an interconnected system without first having students examine each system individually. I did what many a teacher in my position would do: I googled MS-LS1-3 and started vetting the pages I found. I became inspired by a lesson from betterlesson.com, Human Body 2.0, from Mariana Garcia Serrato. I used her project as my template and centered my storyline around this guiding question: What if we could build a better body?

Gathering Evidence

To form a better body, or body system, students need to examine a perceived weakness in our current model/body. As students brainstormed all the ways our bodies could become better, they quickly realized they needed to investigate the current human body system to engineer a better one. To enhance their understandings, students were given several dissection opportunities, lecture videos, mini-labs that could be checked out, textbook pages and web resources. They had two weeks to construct written models (blogs using their G Suite for Education Glogster accounts) summarizing their understandings. Students then commented on one another’s blogs, asking questions about where they saw limitations. In their comments, students were tasked with evaluating understandings independent of their personal biases and practiced making qualitative/quantitative observations. This gave them an initial opportunity to practice strengthening statements by making them empirical.

Article 2: Stating Supported Claims

When students evaluated one another’s comments, they expressed interest in a specific body system, so I had them choose the body system they thought most needed improvements. Students were placed into body system groups of their choice (they ranked their interest in each body system and were assigned to groups based on ranking and availability), then they revised initial models and constructed a physical model for their “Human Body 2.0.” Students spent an additional week preparing prototypes to be shared with the class. On presentation day, students had to evaluate their models and argue effectiveness and feasibility. (See System Evaluation Sheet.)

Article 3: Pairing the SEP and the CCC

One CCC (Crosscutting Concept) for this particular DCI (Disciplinary Core Idea) is systems and system models. Because the NGSS are interconnected, students are sense making through the combination of content, practices, and overarching crosscutting concepts. Encouraging students to make and revise their models as part of argumentation ensures that they not only understand the benefits of their system, but also its limitations. Argumentation is strengthened through modeling, as it uses a natural feedback loop and allows students to see that argumentation is not a “fight,” but a network of understanding based on evidence. It illustrates that the argumentation process is not linear, and keeps conversations, investigations, and—most importantly to me—wonder ongoing.

Ways I hope to improve this unit in the future

- Implement an anchoring phenomenon before the guiding question;

- Continue to become more familiar with NGSS Screener Tools and rubrics; and

- Increase connectedness. I find students create a better model and argument when they know others will evaluate their model. (If you are interested in having our students evaluate your student’s blogs or vise versa, tweet me at @frizzlerichard.)

So when I am asked on the street, at the pool, or anywhere about my argumentative middle schoolers, I smile. My students know how to argue correctly, and as their science teacher, I couldn’t be more proud!

Meg Richard

Meg Richard is a seventh-grade science teacher at California Trail Middle School in Olathe, Kansas. She has been teaching science since 2010 and is a graduate of Central Methodist University and the University of Central Missouri. In addition to her teaching duties, Meg is excited to be a member of Teaching Channel’s Tch Next Gen Science Squad and to work with the Kansas Department of Education as a Science Trainer. She’s passionate about providing authentic, hands-on science experiences for her students, and she often can’t believe how lucky she is to get to do the best job in the world: Teach! Connect with Richard on Twitter: @frizzlerichard.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

I am always amazed at the looks on people’s faces when I tell them I teach middle school. They seem to pity me for having a position I chose and love! They inform me that middle school “tween-agers” are argumentative, stubborn, and at times, adamant about whatever they set their minds to. But I smile because I have the best job in the world!

NGSS Curriculum Integration—Off on a Tangent!

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2017-07-25

The creation of a school garden inspired this fourth-grade unit. All students in the school were responsible for planning the garden, as well as for planting, weeding, and harvesting our crops of tomatoes, pumpkins, and carrots. The harvest was shared with the school cafeteria staff, who prepared salad and dessert bar selections for the students, and our fire department staff, who watered our garden in the summer, providing a community connection. All food scraps were composted, and many seeds were harvested, dried, and saved for use in future gardens.

Judy Hebert and 4th-grade students

The curriculum focus for each grade included the study of specific plant parts. Fourth graders explored how the structure and function of plant leaves would be important for optimum plant growth, a Disciplinary Core Idea focus at this grade level. During their research, students often encountered the term food factories. It was interesting to observe students wondering (on their own!) why that connection existed, then, without prompting, asking questions while they considered potential answers, reflecting NGSS practice.

My students live in an area with large factories that had been staffed by immigrants from their own families. I encouraged students to interview those family members and other relatives to better understand how the factories worked, including the products they made, supplies used in production, and waste that was disposed. Students shared their stories with the class, then wrote journal entries about the parallels between food production of leaves and the manufacturing sites they had observed.

Students were intrigued by the idea that children worked in factories at very young ages, so I introduced the book Kids at Work, which detailed the jobs held by young children, including coal mining, farming, and textile factory work. Child labor laws protecting children from working in dangerous jobs were discussed, and some class groups chose to research the lives that children led before these laws were passed.

During the discussion and journaling activities, I asked the students where most of the factories in their area were located. Students eagerly responded that the factories were all near the river, providing a great example of observing the crosscutting concept of patterns. Next, I asked them to explain, with evidence, why they thought the factories were located near the river. After much discussion, students decided to research reasons for this placement, as they determined that their ideas needed to be supported by more evidence.

Students again interviewed family members, and reviewed (with teacher modeling) the history of the city pertaining to industry. I also included a review of simple machines, focusing on their engineering design, and asked students to again parallel differences between simple machines and the machines used in the manufacturing process in these factories. Students then illustrated how changes made to these machines resulted in enormous gains in production.

As students became more familiar with the manufacturing process, they encountered the term assembly line. As they had done previously with the term food factories, students became interested in creating their own assembly line. They detailed their suggestions for one and shared their ideas with the class. Their practice of planning and carrying out an investigation became a natural progression from their own research.

I asked them to consider these questions: What is the product goal of your assembly line? What materials will be used, and how is waste eliminated? I reviewed the comparisons between raw materials in leaves (CO2, water), light from the Sun, and green material in chloroplasts, and the materials that might be used in the assembly line. This offered another great opportunity to work with patterns and how they influence cause/effect. Students had traveled on such a tangential journey in their research that they needed a refresher on the concept of food production in leaves, since the goal of plant research at all grade levels was the garden’s success . The crosscutting concept of systems and their components was evident during the students’ investigations.

Next, students decided to invest some money (from the PTO fund) to develop craft packets to make Christmas ornaments. They discussed the constraints, most notably the cost! In the gym, all 60 fourth graders were divided into groups, and they passed the packet contents down their assembly lines, with each child responsible for one part of the craft creation. Students at the end of the line wore plastic gloves, examined each piece, and determined whether it needed to be returned for revision. Their quality control was impressive and provided evidence for determining criteria for success!

Students created more than 200 ornaments, which were sold at the annual holiday musical event. Student groups then calculated profits, determined the cost of repaying the PTO investment, then shared their mathematical findings with the class. They presented creative ideas on ways their profits could be spent, with debate and visuals used as enticements. To demonstrate final factory/leaf food production integration, I had students read the book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and journal their ideas for a story called “Charlie and the Leaf Factory.” Their stories provided the connection between literacy and the crosscutting concept of understanding the behavior of systems.

This leaf-function journey allowed students to engage in three-dimensional learning every day. Students observed patterns in nature, constructed explanations of the relationships they observed, then engaged in all aspects of curriculum integration. Social studies, math, and literacy were seamlessly included in their studies. They were so involved and engaged that they shared their findings with students in other grades. Third graders then asked if they could “have fun” (their words!) learning the same material next year. Success!

Judy Hebert

Judy Hebert is a retired K–5 science teacher from Chicopee, Mass. She is currently an NGSS@NSTA Curator focusing on Earth science grade 4. Hebert’s work with students has always had an emphasis on outdoor education. Water monitoring, hiking in state parks, and school gardening have been her major interest.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 Fall Conferences

National Conference

The creation of a school garden inspired this fourth-grade unit. All students in the school were responsible for planning the garden, as well as for planting, weeding, and harvesting our crops of tomatoes, pumpkins, and carrots. The harvest was shared with the school cafeteria staff, who prepared salad and dessert bar selections for the students, and our fire department staff, who watered our garden in the summer, providing a community connection. All food scraps were composted, and many seeds were harvested, dried, and saved for use in future gardens.

STEM Sims: Explosion Shield

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2017-07-24

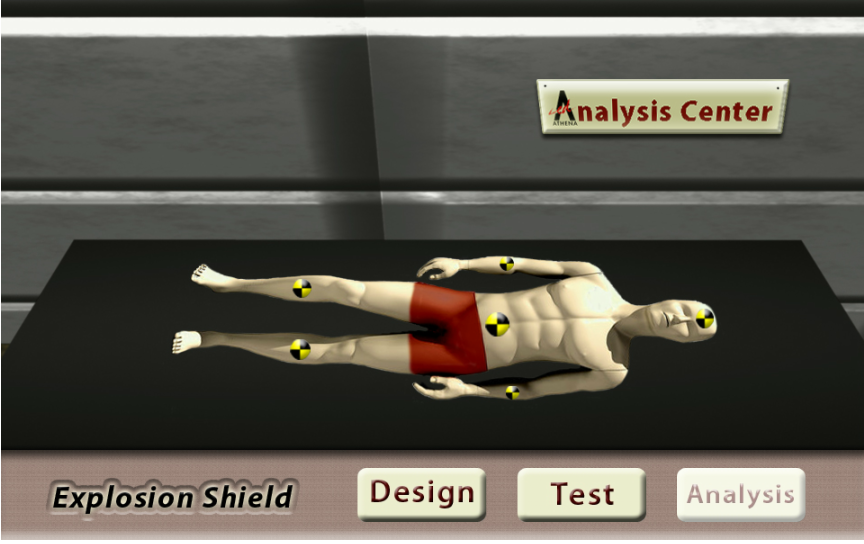

Stem Sims: Explosion Shield

Introduction

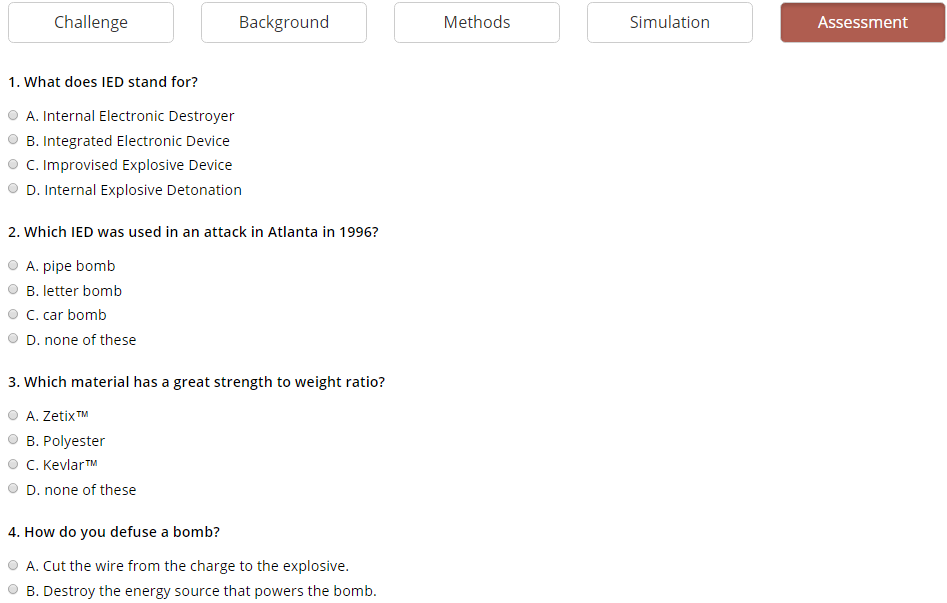

STEM Sims provides over 100 simulations of laboratory experiments and engineering design products for applications in the STEM classroom. Explosion Shield, one of the many valuable simulations offered by STEM Sims, allows students to explore how an explosion can affect different types and shapes of materials. Moreover, students can discover which material combination can offer the best protection. This simulation asks participants to test explosives on different materials, which is a very safe and motivating mechanism to cover this interesting topic. STEM Sims: Explosion Shield is aligned with state standards and the following national (NGSS) standards:

• MS-PS3.C. – Relationship Between Energy and Forces

• MS-ETS1.C – Optimizing the Design Solution

The simulation makes available for students a brochure (see link below) with a pre-assessment quiz and introductory information about the history of explosives and shields. We found that the historical overview gave a nice foundation of content and helped students to learn of advances in technology have changed over time. Moreover, this simulation is a great fit for teachers who want cover learning objectives related to energy and force in a fun and interesting manner that is very safe. Moreover, the deductive reasoning skills that are incorporated will challenge the brightest students to make accurate observations and formulate high-level problem-solving solutions.

Brochure:

https://stemsims.com/simulations/explosion-shield/brochure/brochure.pdf?version=2017-01-10

Sample Assessment

To maximize learning and help teachers in lesson planning, STEM Sims provides two lesson plans for this simulation (see link below):

Lesson 1:

https://stemsims.com/simulations/explosion-shield/lessons/lesson-1.pdf?version=2017-01-10

Lesson 2:

https://stemsims.com/simulations/explosion-shield/lessons/lesson-2.pdf?version=2017-01-10

Conclusion

Explosion Shield is a nice tool for teaching students about how the dangers of energy and force manifested in explosions can be both safe and very interesting. Undoubtedly, the topics covered in this simulation would be too unsafe for actual experimentation. Therefore, by using this simulation, students will be able to explore an area that would otherwise be ignored and at best- speculated. Consider signing-up for a free trial and evaluate this simulation for your future lesson planning and course instruction.

For a free trial, visit:

https://stemsims.com/account/sign-up

Recommended System Qualifications:

• Operating system: Windows XP or Mac OS X 10.7

• Browser: Chrome 40, Firefox 35, Internet Explorer 11, or Safari 7

• Java 7, Flash Player 13

Single classroom subscription: $169 for a 365-day subscription and includes access for 30 students and 100 simulations.

Product Site:

https://stemsims.com/

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Anthony Balos is a graduate student and a research assistant in the secondary education program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania

Stem Sims: Explosion Shield

Learning from experience

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2017-07-23

My first year of teaching biology was challenging, but I made it! Do you have any suggestions for what I should do to improve for next year? —C, Virginia

My first year of teaching biology was challenging, but I made it! Do you have any suggestions for what I should do to improve for next year? —C, Virginia

Congratulations for completing your first year! A good way to prepare for next year is to reflect on this one, learning from your experiences.

How did you know a lesson was successful? What did you do when things didn’t go as planned? Were your classroom management routines and procedures effective? How did you deal with disruptive students? How well were you able to access and use the technologies available in your school? Are there any strategies you would like to consider, in terms of instruction, classroom management, or communications?

Were you surprised by any misconceptions or lack of experience among your students? Should you change the amount of time or emphasis invested in some topics? Did you have an effective combination of content, processes and interdisciplinary connections? Do you have any gaps in your own knowledge base?

Were your lesson plans detailed enough to adapt or modify? How well did assignments and projects align to unit goals and lesson objectives? Did your lab activities go beyond cookbook demonstrations to help students develop their own areas of inquiry? Did you provide opportunities for students to reflect on their own learning (e.g., through a science notebook, comparing their work to the rubrics)?

Did your students seem to enjoy learning science? Did you enjoy teaching and learning with them?

Your reflections can be the basis for next year’s goals. It’s tempting to say, “I’ll think about this when school starts. But if you think, reflect, organize, and plan now, you’ll have more time in the fall for getting your second year off to a good start.