feature

Quest for Survival

Learning about biomimicry and engineering design in first grade

Science and Children—July/August 2023 (Volume 60, Issue 6)

By Samantha Richar, Arianna Pikus, Marisol Massó, Maggie Demarse, Amelia Gotwals, Tanya Wright, and Amber Bismack

Engineering design challenges can be an exciting way for children to creatively use science to solve real-world problems. The inclusion of engineering in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS; NGSS Lead States 2013) allows children to strengthen their science learning through engineering design while exploring engineering practices such as designing solutions. As young engineers begin their work of understanding a problem and brainstorming possible solutions, they may ask questions related to how other engineers have solved similar problems in the past (Cunningham 2017). While these questions may be explored through looking at models of human-made solutions, children can also consider models from nature. Like scientists and engineers, when children model their own solutions after those from nature, they are using biomimicry. In this article, we describe a biomimicry-focused design challenge that is the culminating experience of an integrated science, engineering, and literacy unit and then share how children in Mrs. Portman’s class designed their “bio-inspired solutions” to the challenge.

Quest for Survival Unit

The first-grade “Quest for Survival” unit is part of the SOLID Start (Science, Oral Language, and LIteracy Development from the Start of School; Gotwals and Wright 2017) grade K–2 curriculum. This freely available curriculum integrates science, literacy, and (in some units) engineering to support K–2 students in scientific sensemaking. The unit begins with students examining images of different animals and plants as they consider the unit driving question, How do animals and plants use their parts to survive? The unit consists of 10 one-hour cohesive lessons, with each lesson containing five instructional components: Ask, Explore, Read, Write, and Synthesize (Gotwals and Wright 2017). As children engage in these lesson components, they work toward answering the unit driving question. These lessons also engage classrooms in science discourse to deepen science learning and promote science language development. Wright and Gotwals (2017) found children who participated in the SOLID Start curriculum were significantly more likely to use science vocabulary and engage in scientific arguments compared to children in classrooms who used another curriculum.

The first phase of the unit centers on children’s use of models to investigate how external parts of plants and animals help them survive, grow, and meet their needs. For instance, children engage with models of bird beaks, camouflage, and blubber as well as examples of plant parts/attributes to learn about structures and functions for survival. Children also make observations from videos of animals to consider how parents and offspring use behaviors to survive. For more information on the first phase of the unit, see SOLID Start Curriculum Materials in Online Resources.

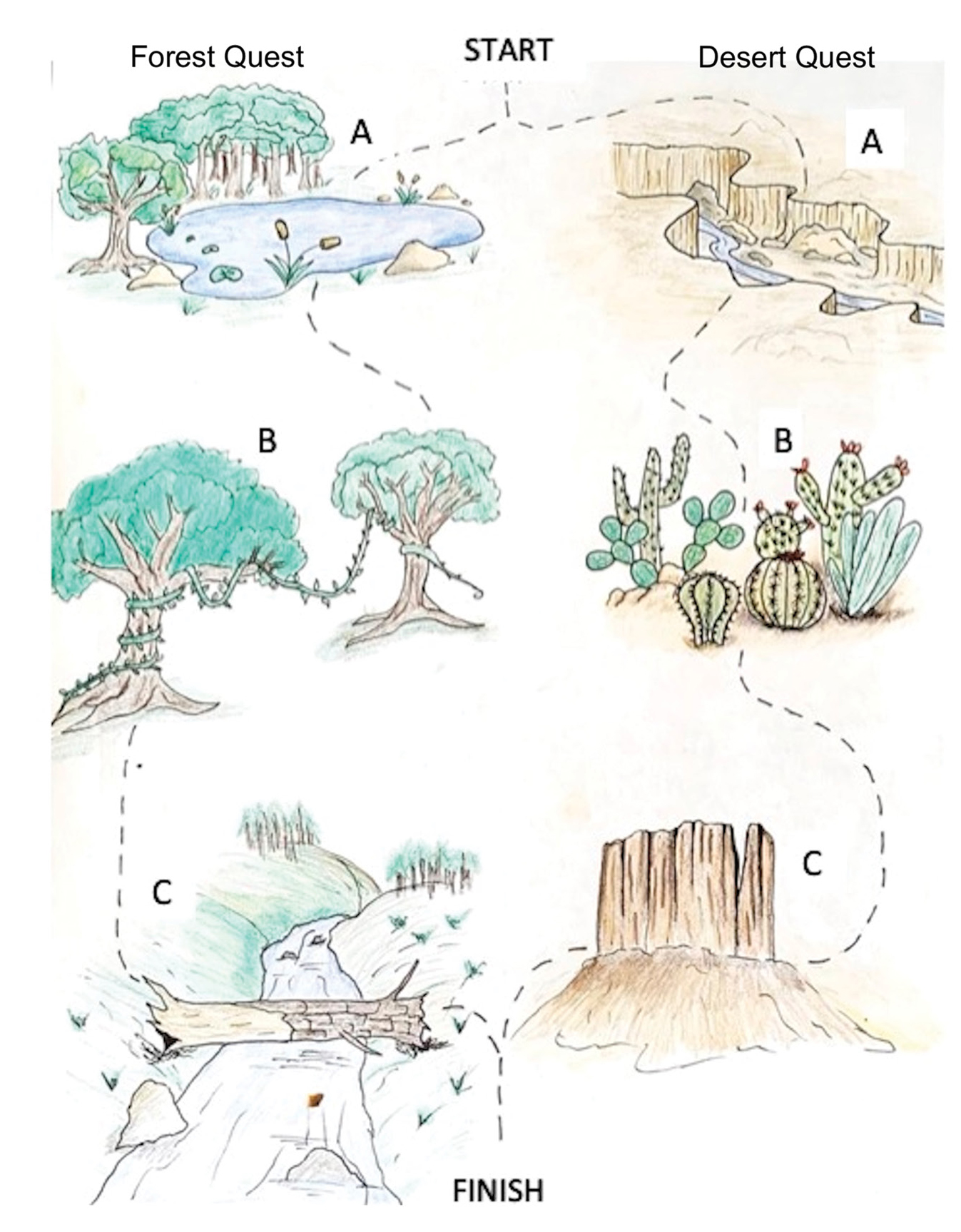

The unit then culminates in an “Adventure Quest” engineering design challenge that spans across three lessons and deepens children’s learning from the first phase of the unit. In the challenge, first graders work in teams to complete either the Forest Quest or the Desert Quest, both of which contain obstacles based on challenges a person may encounter within those habitats (see Figure 1).

Adventure Quest.

Forest Quest Challenges

- Camouflage

- Swim across a pond

- Climb and swing on vines

- Balance across a log

Desert Quest Challenges

- See in the dark at night

- Cross a canyon

- Move through prickly cacti

- Climb a rock formation

In this final phase of the unit, children research and design a solution that uses biomimicry as they use the structure of an animal or plant part to inspire them to complete their given quest.

Designing Bio-Inspired Solutions to the Desert Quest

The following sections focus on the essential activities children engaged in as they designed solutions using biomimicry to the Desert Quest challenges.

Figuring Out How Engineers Use Biomimicry

Connect to Prior Learning

In the first engineering focused lesson, Mrs. Portman brought the class to a circle on the carpet and displayed the question, How do some human-developed objects mimic plant and animal structures and functions? along with images of plants and animals with unique structures, for example a turtle. She led a turn and talk about the images and challenged children to think if they know any human-made objects that have similar structures or functions.

Mrs. Portman: What do you notice about how plants and animals use their body parts to survive? How do you think these might be helpful in human inventions?

Luca: I remember the turtle has a hard shell to protect it.

Sasha: It looks like a helmet!

Mrs. Portman: Does anyone want to add to that idea?

Martina: I also think a shell and helmet look the same and they can both protect.

Discussion during the turn and talk supported children in making connections between their prior learning and the ideas underlying biomimicry. Student talk also allowed Mrs. Portman to observe the children’s initial understanding of the lesson question.

Discuss Texts and Models

Mrs. Portman then introduced the first graders to the Adventure Quest challenges and the idea that engineers can use biomimicry when designing solutions to problems. Mrs. Portman explained the idea of biomimicry by guiding the class through a discussion of how engineers have used biomimicry to solve real-world problems. For instance, Mrs. Portman conducted an interactive read-aloud around the informational text How and Why do People Copy Animals (Kalman 2015). She prompted children to discuss examples of how design solutions from the text have been developed to solve problems by mimicking the structure of animals and plants, such as how the colors of clothes model the function of animals’ fur to hide from predators, protect themselves, or capture prey.

Children discussed more examples of biomimicry while watching videos of scientists and engineers explaining how they used plants and animals as inspiration to develop solutions to problems. For example, children learned how the Japanese bullet train is modeled on the structure of birds, including the wings of an owl, the belly of a penguin, and the nose of a Kingfisher. Discussing models of solutions that used biomimicry within various texts allowed first graders to consider how other engineers, both humans and those from nature, have solved similar problems. These models also laid a foundation from which children could begin brainstorming and designing their own solutions.

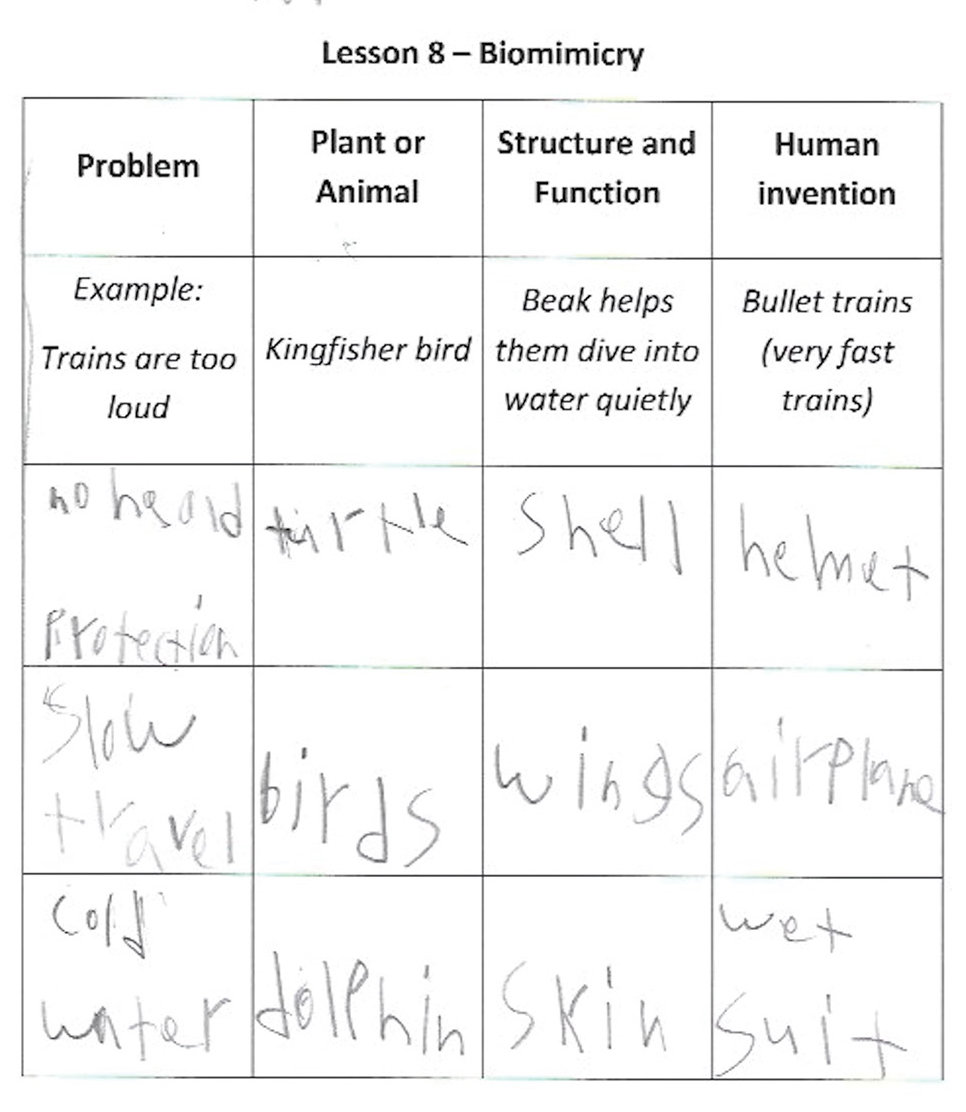

Research Ideas

To support children in obtaining information about different plant and animal structures that could inform their design solutions, Mrs. Portman arranged research materials for each quest that included age-appropriate informational texts and technological devices with preloaded child-friendly videos and websites (see Online Resources). Prior to this activity, she collected children’s preference of which Quest challenge they would like to complete to determine the groups and help decide which materials to prepare. During science time, Mrs. Portman transitioned children into small groups in different areas of the classroom and passed out research materials specific to the group’s Quest challenge. For instance, children designing solutions to cross the canyon watched a video about how birds fly using feathers and strong muscles attached to their wings. Mrs. Portman gave children a student sheet with a graphic organizer to record information they found from the various resources (see Figure 2). Mrs. Portman gave children about 30 minutes to do their research and she circulated from group to group to support first graders with their reading and writing. Teachers may however consider facilitating this part of the lesson in different ways. Another possibility is building the research component of the lesson into guided reading groups outside of traditional science time.

Biomimicry research graphic organizer.

As children researched, Mrs. Portman reminded the first graders of their school’s safe technology use guidelines, especially to stay on the websites and videos needed for science and to carry technology with two hands if it needed to be moved to another spot in the classroom. As children gathered information from various sources, she asked guiding questions to support their figuring out.

Mrs. Portman: What animal or plant are you reading about?

Kyle: Birds.

Mrs. Portman: What are some structures birds use to survive?

Kyle: They have wings that help them to fly.

Mrs. Portman: I wonder, do you think engineers have designed anything that mimics bird wings?

Kyle: Airplanes have wings, too.

Research was an important preliminary step for first graders to make connections between animal and plant structures they have learned about throughout the unit and how engineers may mimic those structures to solve problems.

Designing Solutions

Brainstorm Ideas

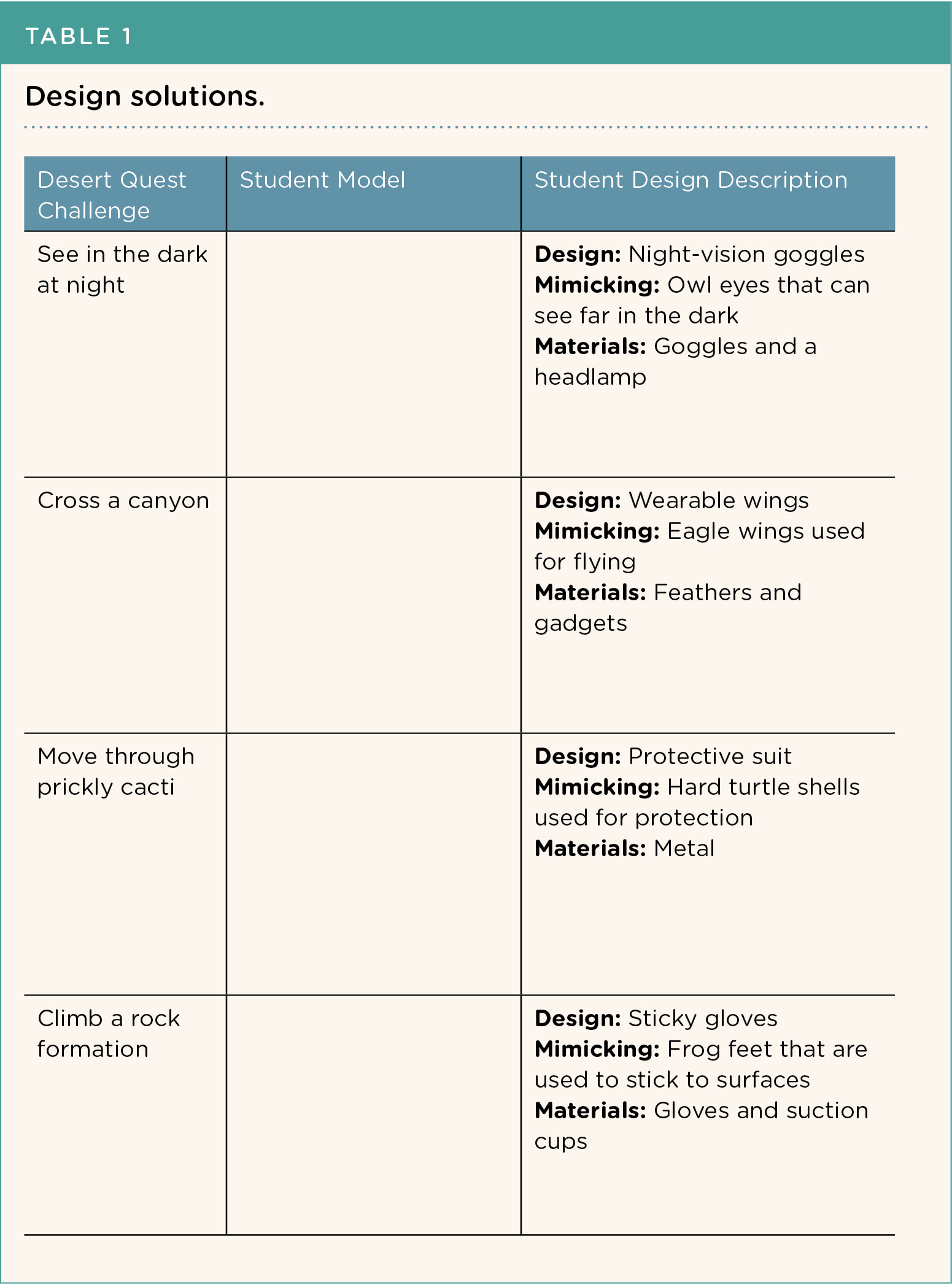

In the next lesson, first graders continued the design process and began designing their own models that use biomimicry. Children worked in teams to share their ideas about how and why the structures of plant and animal parts solve a particular problem. Mrs. Portman made the teams by grouping four or five first graders together by Quest, making sure there was at least one child designing a solution for each challenge per group. Working in teams allowed children time to discuss their ideas before and during writing them on their design plan student sheets. For instance, two first graders designing a solution to see in the dark discussed their initial ideas. They debated whether they should mimic how fireflies glow or try to design a way to see farther in the dark, similar to an owl. They decided to mimic an owl because of how far an owl can see in the dark. Then, they discussed making a pair of goggles and brainstormed what materials might best help human eyes see farther in the dark. They considered using materials like a headlamp, glasses with lights, or glow-in-the-dark eyes in their solutions. Children’s models for each Desert Quest challenge can be found in Table 1.

Design solutions.

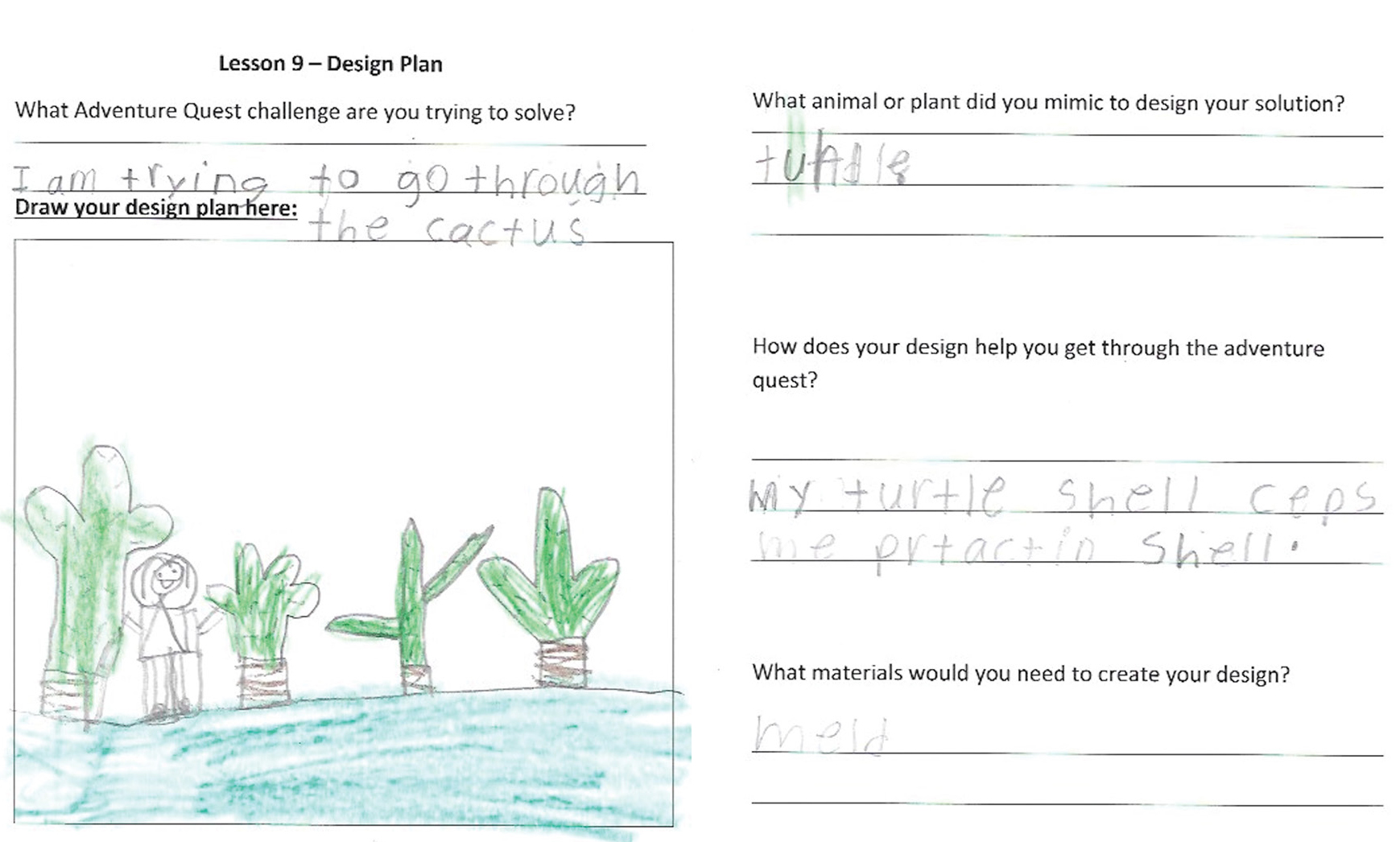

Create a Design Plan

In addition to discussing ideas, first grade engineers also wrote individual design plans where they identified the animal or plant they chose to mimic, explained how the design helps them get through the adventure quest, and listed the materials necessary to create the design. One child who was designing a solution to safely move through the prickly cacti illustrated an armored suit and wrote about how he was inspired by the shell of a turtle for protection. The engineer showed the materials by drawing a silver suit and wrote he would use metal (see Figure 3).

Student design plan.

While the students worked on their design plans, Mrs. Portman circulated from group to group to check in with the young engineers. To formatively assess their progress, she observed children’s design plans and asked questions aligned to the NGSS performance expectation 1-LS1-1 (see Table 2).

Assessment Statement #4: Students can plan and design a solution for a human problem by mimicking plant or animal external parts.

|

Discussion Prompts |

Look for/Listen for |

|

What animal or plant part are you mimicking to solve your challenge? How are you designing a solution based on this animal or plant part? How does it help you to solve the challenge? What materials might you need if you were to build this solution?

|

Students to share their ideas about how and why humans would mimic the structures of plant and animal parts to solve particular human problems (e.g., mimic turtle shells when making bicycle helmets for protection). How students use the structures of the parts and how they help the plant or animal survive, grow, or meet its needs to inform the engineering design.

|

Test and Redesign Solutions

Following the steps of the design process, first graders also shared their solutions with other groups to give and receive feedback with the purpose of revising their designs. Mrs. Portman had them use sentence stems such as, “One thing you might change is …” or “Have you thought about adding …?” This was also an important time for children to test their solutions. For instance, Ava designed a pair of gloves that mimicked the sticky feet of a frog to help her climb the tall rock formation obstacle. Her original idea was to use tape, but she was not sure if it would be strong enough. While she discussed her concern with her group, Mrs. Portman gave her tape to try out in the classroom. Ava attached it to her hands and used it to try to climb up the classroom wall, but it was not strong enough. Mrs. Portman then prompted her team members for suggestions:

Mrs. Portman: What suggestions do you have for Ava to use instead of tape?

Martina: One thing you might change is using suction cups.

In the exchange above, children provided feedback that recalled prior learning and presented new ideas. The original designer changed her design plan and decided to use the suction cups instead of tape on the glove solution she designed.

Communicate Ideas

After reviewing peer feedback and making any necessary changes to the designs, each team shared their solutions. Mrs. Portman gave teams time to plan what part of the solution each team member would share as well as time to practice. Teams then displayed their work under the document camera and explained their solutions. The team described in the sections above presented one solution to each of the four challenges in the Desert Quest. They mimicked the far-seeing eyes of an owl to see in the dark, the feathered wings of an eagle to cross the canyon, the shell of a turtle to safely move through the prickly cacti, and finally mimicked the sticky feet of a frog to climb the rock formation (see Table 1). Mrs. Portman asked clarifying questions throughout to be sure each team talked about their design, the animal or plant they mimicked, how the design would help them solve the quest, and the materials they would use. She recorded evidence of what students said and showed on their design plans on a formative assessment table (see Online Resources).

Conclusions

The Adventure Quest in the Quest for Survival unit presented children with a real-world inspired problem that required their knowledge of how plants and animals use their external structures for survival to design solutions using biomimicry. Children’s experiences also showed the excitement about science that an engineering challenge can bring to elementary classrooms. After the last team shared their solutions, Mrs. Portman’s announcement, “Team Desert has crossed the finish line!” could barely be heard over the class’s applause and cheers of “It was a success!”

Acknowledgment

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 1620580.

Resources

Kalman, B. 2015. How and why do people copy animals? St. Catherine, ON: Crabtree Publishing Company.

Online Resources

SOLID Start Curriculum Materials: https://education.msu.edu/research/projects/solid-start/curriculum

Samantha M. Richar (danzige9@msu.edu) is a research assistant at Michigan State University College of Education in East Lansing, Michigan. Arianna Pikus is an assistant professor in the Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. Marisol Massó and Maggie Demarse are doctoral students, and Amelia Wenk Gotwals and Tanya S. Wright are associate professors, all at Michigan State University. Amber S. Bismack is an assistant professor of K–12 science education at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan.

Biology Engineering Evolution Life Science Elementary Grade 1