Pairing Literacy and Science to Effectively Teach Argumentation

By Judine Keplar and Carrie Launius

Posted on 2019-09-17

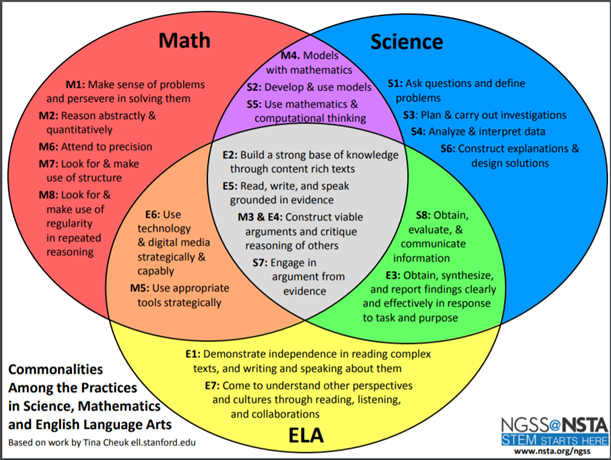

Most elementary teachers, have many opportunities to learn best practices in English Language Arts (ELA), but few in science. Three years ago David Crowther, NSTA past president (2016–17), said in his conference keynote, “Of the eight practices of science and engineering, four of them are language intensive and thus require students to use multiple domains of language, including nonverbal modalities, and a range of language registers,” This challenged our thinking about how the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in English Language Arts (ELA) taught argumentation to elementary students. Argumentation is not mentioned anywhere until middle school, yet the Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs) require students to not only think about argumentation, but also to begin to practice it as young as kindergarten.

Lee (2017)[1] notes another key difference in contrast to the CCSS, in which the term argument is withheld until grade 6: The NGSS expect children from as early as kindergarten to construct an argument with evidence. Thus, “the practice of arguing from evidence is expected consistently throughout K–12.” (p. 97) Since the NGSS indicate that argumentation can be taught and used in the elementary grades and that asking our young scientists to engage in argumentation isn’t an impossible task, the question becomes How?

After examining the NGSS progressions for the SEPs, it is quite evident that argumentation needs to be introduced at the start. For most elementary teachers, ELA is what they know, so we decided to use a book to help students identify argumentation, and see if they would be able to make claims about the evidence that is presented in the book. We knew that integrating ELA and science was going to be a challenge.

One book that helps to illustrate argumentation and collection of evidence is the classic Starry Messenger by Peter Sis (ISBN 978-0374470272). Written for grades 1–6, this book tells the story of Galileo Galilei and how he used the findings of Copernicus to reiterate that the universe as he knew it was heliocentric. Copernicus realized he did not have enough evidence to proclaim his findings, but he took copious notes so that someone else could use them to not only make the claim that the Earth revolves around the Sun, but also have the evidence to prove the claim’s validity.

The book presents three opportunities for students to identify types of arguments. Although we know from history that religion played a major part in the belief that the Earth was the center of the universe, the book only briefly touches on the point, saying, “It’s tradition.” This gives us the first opportunity to discuss arguments. At this point, we ask our students questions to help them begin to identify differences among arguments. For younger students, ask, “Just because it is a tradition, does that make it a fact or true?” Ask them to further explain what they believe. For students in grades 3–5, questions should be more open-ended.

The second opportunity to discuss argumentation comes at the point in the book when Copernicus has gathered many findings, but says he cannot publish them. Ask students, “Why do they think Copernicus is not able to make a claim and argue about his findings? What might he be missing?” Students in grades K–5 will be able to discuss what they think. During the discussion, students will be presenting their own arguments. Ask them to give examples from the book supporting their thinking.

Galileo had evidence to support that the Sun was the center of the solar system, but he was persecuted for his findings. Students have the opportunity to not only argue whether he was treated fairly, but more importantly, why his discoveries were accurate and what evidence he had to support his findings.

Asking high-level questions like What are the differences among the various arguments presented in the book? Provide evidence to support your claim; and If you were born at the time of Galileo, which side would you take and what evidence would you provide? allow students to engage in SEP at the elementary level.

K–2 grade band

- Identify arguments that are supported by evidence.

- Distinguish between opinions and evidence in one’s own explanations.

3–5 grade band

- Distinguish among facts, reasoned judgment based on research findings, and speculation in an explanation.

By using trade books to engage students in the SEP of argumentation of evidence, they will have a plethora of opportunities to use argumentation well before they are asked to do it in an ELA classroom. Christine Royce, NSTA retiring president (2019–2020), offered the thought that “Explicitly modeling for students and providing them opportunities to learn about and compare/contrast the use of evidence is one such opportunity to utilize a cross- discipline practice. The increased connections between experiences in which the students participate assists them in transferring their learning. Finding the overlap between argumentation in the science classroom and literacy studies will provide students opportunities to develop, consider, and respond to ideas in writing, verbally and scientifically.”

We are reminded of this every day as we examine the graphic below.

Reference

[1] Common Core State Standards for ELA/Literacy and Next Generation Science Standards: Convergences and Discrepancies Using Argument as an Example, Okhee Lee https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/0013189X17699172

Judine Keplar is English Language Arts Curriculum Specialist for St. Louis Public Schools in St. Louis, Misssouri, and also serves as the current president of the Board of Education in Belleville Public School District 118 in Belleville, Illinois. She is a passionate promoter of cross-curricular literacy at all grade levels and enjoys her work writing curriculum and providing professional development around all things literacy-related. She resides in Swansea, Illinois, with her husband and two children.

Judine Keplar is English Language Arts Curriculum Specialist for St. Louis Public Schools in St. Louis, Misssouri, and also serves as the current president of the Board of Education in Belleville Public School District 118 in Belleville, Illinois. She is a passionate promoter of cross-curricular literacy at all grade levels and enjoys her work writing curriculum and providing professional development around all things literacy-related. She resides in Swansea, Illinois, with her husband and two children.

Carrie Launius is Science Curriculum Specialist for St. Louis Public Schools in St. Louis, Missouri. She previously was the NSTA District XI Director and president of Science Teachers of Missouri (STOM). She believes using trade books to support science learning is essential for students. She was instrumental in developing and implementing the Best STEM Book Award for NSTA-Children’s Book Council. Her passion is supporting teachers and helping them grow professionally. She resides in St. Louis near her two grown children and with her son and four dogs.

Carrie Launius is Science Curriculum Specialist for St. Louis Public Schools in St. Louis, Missouri. She previously was the NSTA District XI Director and president of Science Teachers of Missouri (STOM). She believes using trade books to support science learning is essential for students. She was instrumental in developing and implementing the Best STEM Book Award for NSTA-Children’s Book Council. Her passion is supporting teachers and helping them grow professionally. She resides in St. Louis near her two grown children and with her son and four dogs.

Note: This article is featured in the September 2019 issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

Interdisciplinary Literacy Science and Engineering Practices Elementary