Feature

The BEST Partnership Program

Supporting Students With ASD by Connecting Schools, Museums, and Occupational Therapy Practitioners

Connected Science Learning April-June 2019 (Volume 1, Issue 10)

By Katie Slivensky, Ellen Cohn, Alexander Lussenhop, and Christina Moscat

People with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) become more widely recognized as part of our population every year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, about 1 in 59 children in the United States is on the autism spectrum (CDC 2018). In 2011 and 2012 more than 455,000 U.S. students received special education under the disability category of autism (DOE 2013). Although support for these students is increasing in schools nationwide, students with ASD are still currently underserved in community settings outside of the classroom, participating less frequently in social activities and experiencing limited variety in nonschool related activities (Little et al. 2014).

Informal learning centers such as museums have made creative strides to become more inclusive, but people with ASD still experience barriers in such settings (Lussenhop et al. 2016). One common barrier is that youth with ASD are often prevented from participating in field trips alongside their fellow schoolmates during regular venue operating hours, due to perceived difficulty with accommodating these children’s needs in community settings. Students with ASD deserve the opportunity to visit and learn from informal science educational institutions and to be included in their local community, not separated from it (Hall 2010).

As part of its mission to encourage young people of all backgrounds to explore and develop their interests in science and technology, in 2013 the Museum of Science, Boston (MOS), established the Buddies Exploring Science Together (BEST) Program, in collaboration with the occupational therapy program faculty and graduate students at Boston University’s Sargent College (BU OT), as well as Boston Public Schools (BPS). The BEST Program supports students with ASD so that they can engage in field trips to the MOS during regular operating hours over the course of multiple months. The program aims to increase student interest in science and provide opportunities for students with ASD to socially participate in a community setting. This novel approach has resulted in science learning opportunities and positive social outcomes for these students, as demonstrated by program evaluations conducted by BU OT graduate students and MOS research and evaluation staff. Additionally, this is a highly replicable partnership program for other communities to modify and implement.

How the BEST program works

The BEST Program is structured to meet the needs of students with ASD and support these students in achieving the following four goals:

- Engage in science learning opportunities, which connect to everyday life

- Be with and/or socially communicate with others in a naturally occurring community setting

- Be interested in and excited about science

- Feel included in a community setting

The BEST Program takes place at the MOS from January through April of each school year. The program consists of six field trips to the museum and multiple visits to the classroom, including two initial observational visits from BU OT, a previsit by MOS educators and BU OT a week before the first field trip, a midvisit by MOS educators, and finally, a postprogram visit by BU OT to reflect on the experience. The midvisit is to provide continuity during the BU spring break in March.

The BPS classrooms involved are ASD Strand classrooms, which means all of the students in the classroom are students with ASD. In 2019 two BPS schools participated in the BEST Program: Orchard Gardens K–8 School, which brought 10 students from one middle school classroom (grades 5–8), and Jackson/Mann K–8 School, which brought 16 students from two middle school classrooms (grades 5–8). Students from Orchard Gardens visited on Wednesdays and students from Jackson/Mann visited on Thursdays for the duration of the program. A teacher and three to five paraprofessionals/one-on-one assistants visited along with students from each class. In addition, two BU OT students worked with each class, totaling six BU OT students, with two participating on Wednesdays and four on Thursdays. Finally, three MOS educators rounded out the team for each program day. The ratio of adults to students was approximately 1:1.5.

The participating BPS schools’ special education faculties choose topics to support their science curriculum needs and—in collaboration with the BU OT students—MOS educators then create specific weekly themed program modules based on these science topics. For example, BPS students who learn about the solar system in their classroom can then apply and further their knowledge by participating in a planetarium show at the MOS. Each year prior to the start of the program, BEST Program adult participants—MOS educators, BU OT professors and students, and BPS special education faculty—meet to identify science topics and plan learning activities for the year, based on the requests of the BPS teachers. The BPS teachers and special education faculty members place a great deal of value on the program, as described by one special education teacher who participated in 2015:

“I’ve been teaching for nine years and this is the single most important thing that has happened in my career in teaching as far as having integration of community outing, learning about curriculum, and socializing skills.”

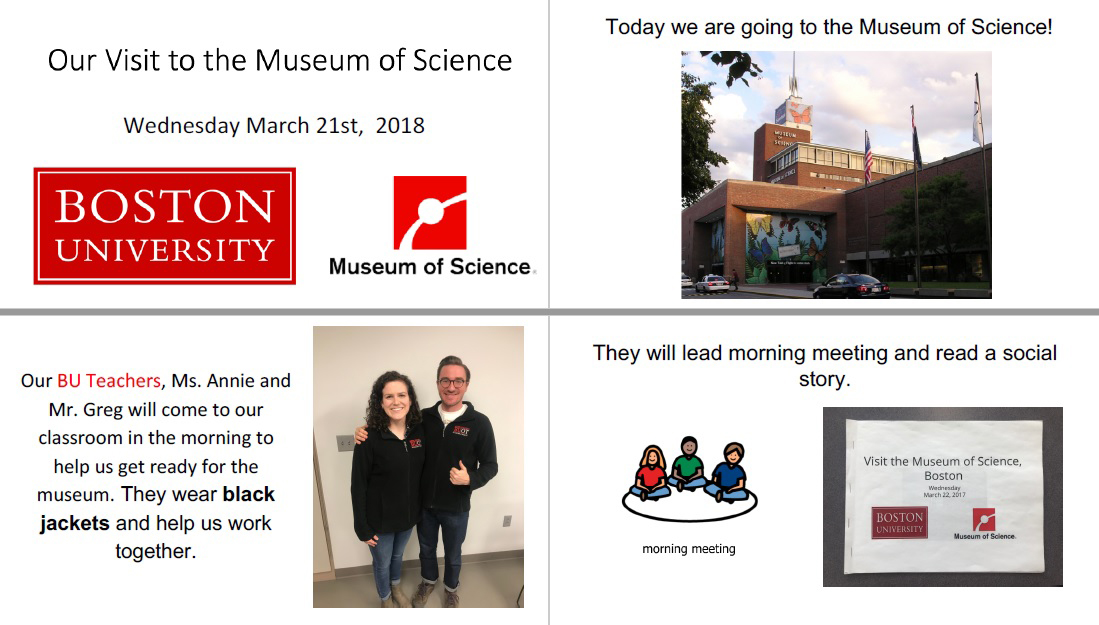

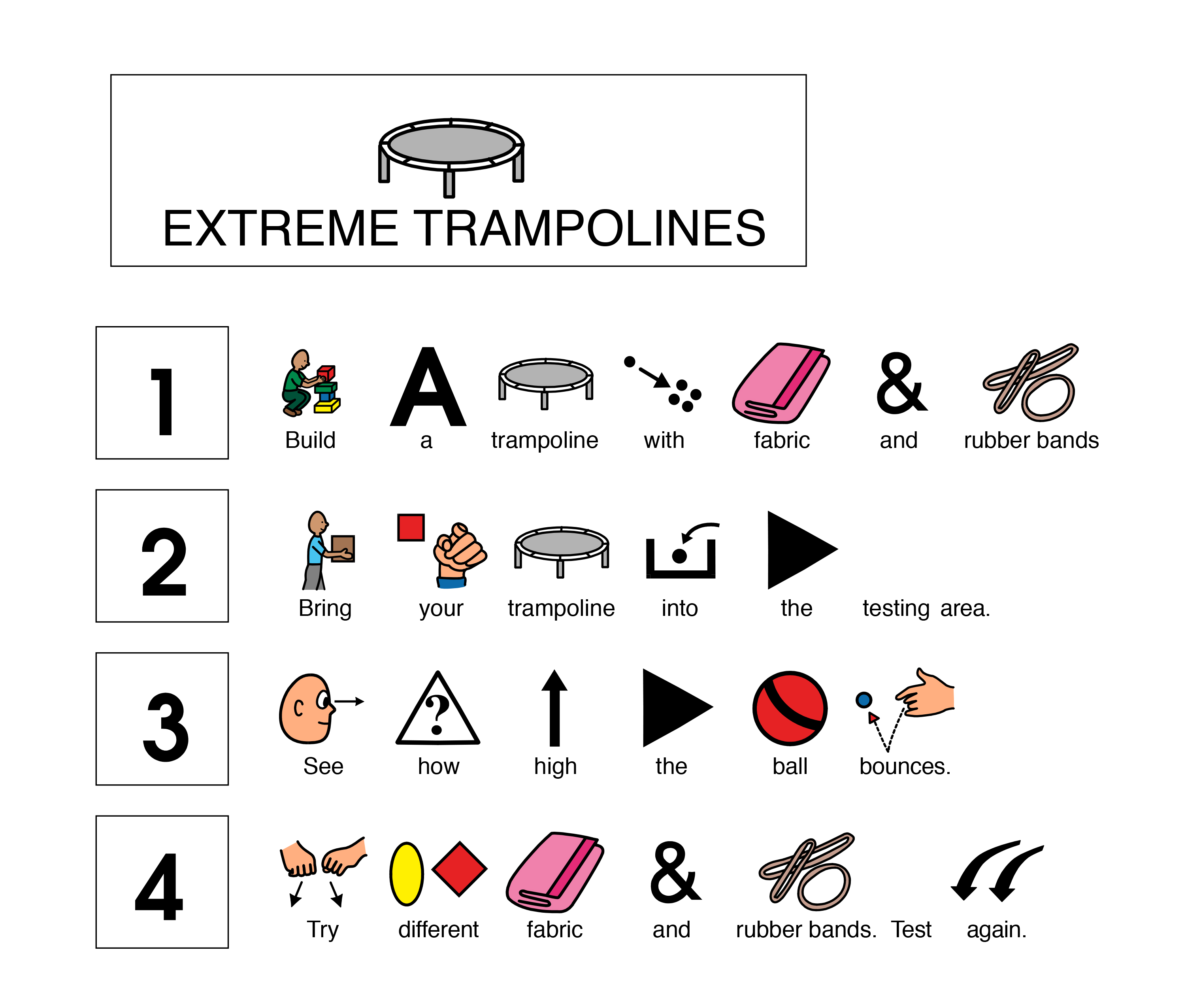

Each week of the BEST Program, the BU OT students engage the students with ASD in an individualized goal-setting process and read customized social stories at their schools prior to getting on the bus to travel to the museum. Social stories are designed to prepare students for an upcoming experience by reviewing what to expect or anticipate and identifying strategies for managing behavior during novel social situations (Kokina and Kern 2010). An example of the first four pages of a social story can be found below.

When the BPS students arrive at the MOS, the BU OT students and MOS educators colead a welcome session and the BU OT students follow up with a warm-up activity—typically, a brief social activity related to the science theme of the day. A warm-up activity for an animal-themed day, for example, could include the BPS BEST Program students each naming their favorite animal, either vocally or via a communication tool such as a tablet, and then demonstrating an action that represents that animal. For each animal named, the whole group would then copy the action the student demonstrates while a BU OT student reiterates, “(Student name)’s favorite animal is a dolphin!”

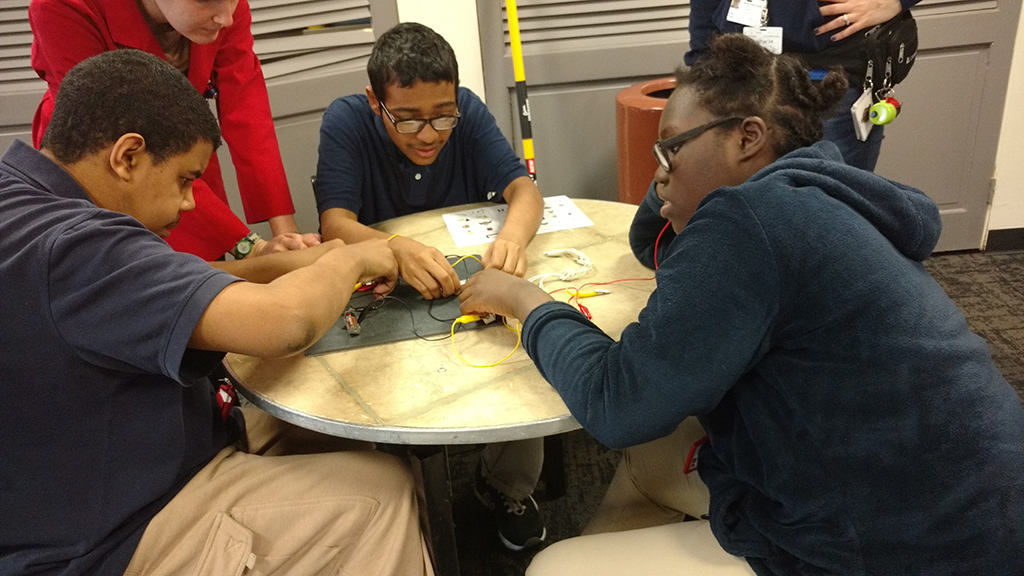

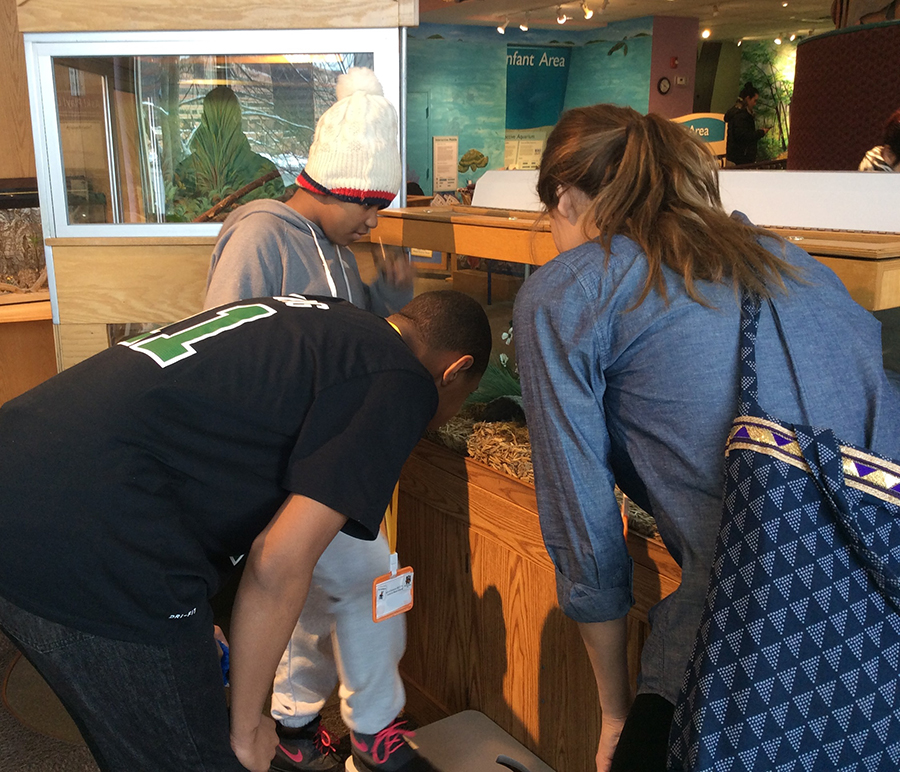

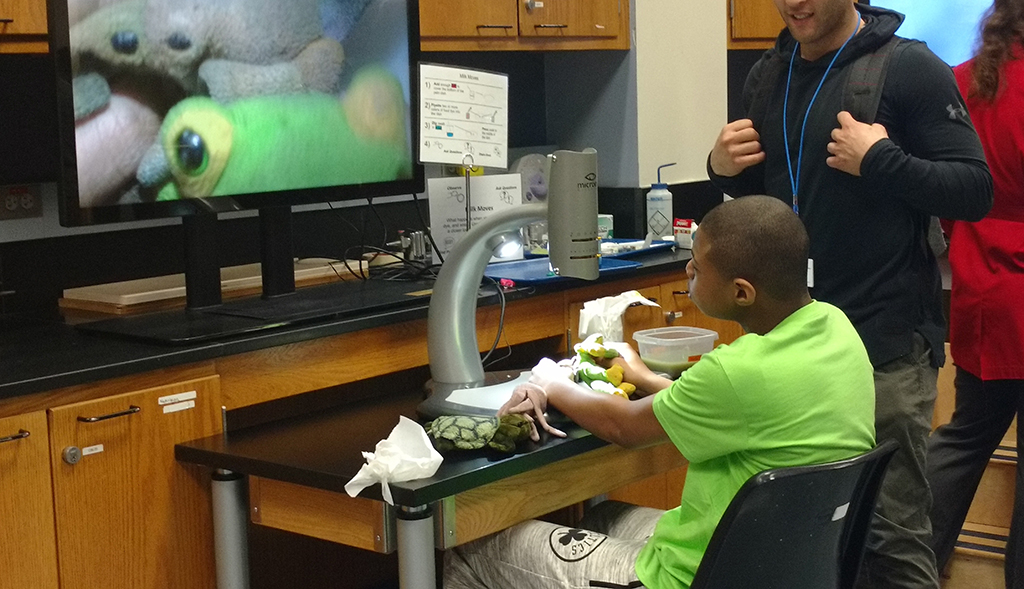

Every MOS visit includes museum presentations, hands-on and socially interactive activities, or exhibit exploration—all collaboratively designed to promote social interaction and science learning. Experiences have included planting seeds and observing their growth, flower dissection and pollination, participation in an interactive Super-Cold Science presentation, a visit to a planetarium show, weekly weather observations with meteorological tools, participation in a Theater of Electricity presentation, and a visit to the MOS Live Animal Care Center.

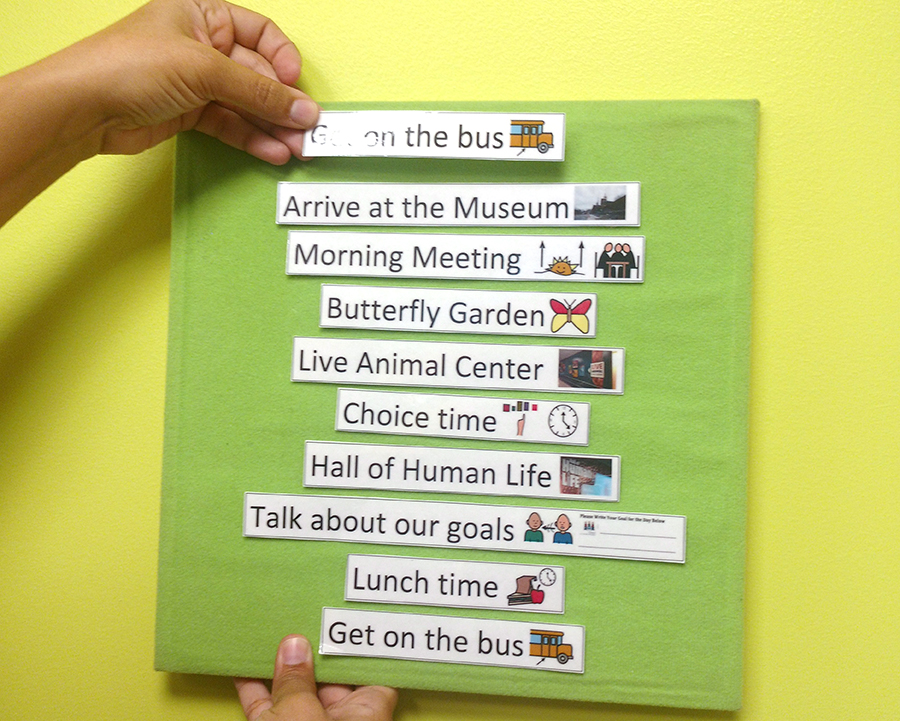

The program also uses tools to support student learning and communication, such as electronic tablets for visual aids; customized, sequenced instructions for experiments; word banks with images for observations, created with the image-software BoardMaker; and visual schedules of the field trip activities that students can follow along with and modify as the visit progresses.

This program has historically been funded via a variety of grants and currently receives most of its funding from a generous grant from the Liberty Mutual Foundation. Everything is fully funded for the visiting students, including admission, bus travel, lunch, and any add-on venues, such as tickets for the Charles Hayden Planetarium or the Butterfly Garden. This grant also supports program material purchases and some MOS staff time.

The BEST Program’s philosophy

The overarching philosophy of the BEST Program is to create an inclusive environment within the typical daily atmosphere of the MOS. Supporting students with ASD as they socially interact in a naturally occurring community setting has been shown to be desired by school personnel and students’ families, and is therefore a major goal of the BEST Program (Lussenhop et al. 2016). Rather than host students with ASD during a separate time or at a separate location from other MOS visitors, the BEST Program scaffolds students’ visits to support their participation in museum activities along with the general museum field trip population. This approach to inclusion is an alternative to the often-used model of offering early access or after-hours experiences.

According to the Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education’s Access Inquiry Group, the inclusion of people with disabilities means that their surroundings enable them to physically interact with the space, cognitively engage with the materials, and socially interact with one another (Reich et al. 2010). Science centers and museums provide ideal environments to foster social engagement for a wide range of audiences because of the interactive nature of their exhibits and the field’s push toward universal design (Reich et al. 2010). In addition, there is emerging evidence that individuals impacted by ASD are more likely than others to have an aptitude for analyzing or constructing rule-based systems to explain the world around them. These abilities are particularly relevant for STEM-related (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields (Wei et al. 2013). Thus, a science center/museum provides a highly interesting and motivating context for students with ASD to socialize and succeed in a community setting, while reinforcing their interests and aptitude for understanding science.

At the MOS, BEST Program students explore the exhibit halls, participate in hands-on activities, and attend live presentations alongside the general museum visitor population (see video below). As outlined in the previous section of this article, the BEST Program includes specifically designed elements to support students in exploring scientific phenomena and interacting socially within the context of a typical field trip at the museum. It is these elements that translate the program’s philosophy into measurable success. This distinctive and innovative methodology places the program in a prime position to change and advance museum practices nationwide to be more inclusive.

The collaboration

To achieve this goal of inclusion in a museum setting, the BEST Program relies on the MOS’s community partnerships with BPS K–12 education professionals and the BU OT graduate program. The connections between social and science learning for students with ASD are expertly brought together by this full team of professionals.

Occupational therapy practitioners focus on supporting “engagement in meaningful occupations.” They analyze the demands of an activity, a person’s abilities, and the context or environment in which the occupation or activity takes place, and then intervene to support participation. The term “occupation” in the profession’s name refers to all the activities that occupy people’s time, enable them to construct an identity, participate as fully as possible in society, and provide meaning to their lives (Cohn, Schell and Crepeau 2010). As such, occupational therapy practitioners have a unique perspective and valuable skills particularly well-suited to collaborating with museum and K–12 professionals to create experiences that promote inclusion and belonging for students.

The BU OT graduate students observe students with ASD in their classroom settings to understand the BPS students’ learning styles and interests, and analyze possible MOS experiences and exhibits to include in the BEST Program. The BU OT graduate students then make recommendations to the MOS educators regarding strategies for structuring the field trip learning experiences to facilitate social interaction and science learning. BPS teachers provide valuable insights as to how MOS educators and BU OT graduate students can best engage the students with ASD, both individually and together as a class. BPS teachers also provide integral structural components and curriculum connections to science learning. MOS educators provide expertise on the museum itself, such as how best to use its spaces and what kinds of presentations and activities are available; they also lead science activities and coordinate program logistics and funding. Collaboration between all partners—the science center, the school system, and the occupational therapy program—is essential for the BEST Program to run successfully.

Program evaluation

Each year, evaluation of the BEST Program has shown that the program promotes social participation and engagement in science learning activities for students. Program evaluation was conducted collaboratively by BU OT graduate students and MOS research and evaluation staff, and has used several different data collection methods, including:

- weekly naturalistic and systematic observations of behaviors of BPS students (in 2015 this was 14 students; in 2018 this was 20 students);

- weekly self-reflections of students with ASD regarding their social and science goals, sense of belonging at the MOS, and interest in MOS activities;

- group debrief sessions among professionals; and

- pre- and post-teacher surveys about students’ behaviors in museum and classroom settings, which were created by adapting standardized surveys from the literature.

The naturalistic observations were a part of the evaluation of the 2015 and 2018 BEST Program. In these observations, students’ engagement in program activities were rated on a scale that ranged from “disengaged” to “neutral” to “engaged,” according to defined criteria. To define behaviors that would indicate engagement in the science museum environment, evaluators drew on data from the 2014 BEST Program evaluation, as well as other research conducted collaboratively by MOS staff and BU OT faculty about how family groups with a child with ASD engage in the museum (Lussenhop et al. 2016). Evaluators took care to note and honor the multiplicity of options for engagement, as forms of engagement are variable and each student has a unique communicative style. Examples of ways in which MOS evaluators could observe whether students were engaged included:

- students completing the steps of the activity;

- observing experiments, animals, or actions of others;

- responding to educator questions; or

- focusing on and using an exhibit component.

Evaluators also noted when students had positive reactions to the activities or made some kind of connection between museum activities and familiar situations, objects, or experiences.

This systematic method for observing student engagement demonstrated that during the 2015 BEST Program, all 14 observed students engaged in science learning activities, almost all (13 of 14) students had positive reactions to these activities, and half made connections between science and their everyday lives. Two students participated in the program but were not observed, as their parents or guardians opted not to consent to their participation in the evaluation. In the 2018 program these findings persisted: All 20 observed students engaged in science learning activities, almost all (17 of 20) displayed positive reactions to the activities, and eight out of 20 students were observed making connections to their everyday lives. In 2018 six students participated in the program but were not observed, as their parents or guardians opted not to consent to their participation in the evaluation.

Examples of positive engagement can illustrate the program’s success for a range of students. For example, in 2015 one student in the program used an electronic tablet to communicate and rarely contributed to group discussions. However, during the sixth and final MOS visit, during a Super-Cold Science presentation, the MOS educator leading the program asked students to make a prediction about a balloon she was using in the show. The student excitedly raised her hand and used her tablet to make a prediction that the balloon would be wet. The student’s teacher shared in the 2015 staff debriefing session that the week after the last MOS visit, the student used her tablet to say, “Bus. Bus. Dinosaur. Butterfly.” She then pointed to her coat because she was ready to go to the museum again. Her teacher said, “For her to even want to say something—that never happened at the beginning of the year.”

Students were also observed making connections between the science learning activities and everyday life in 2015 and 2018. In 2018 at an exhibit about dinosaurs, one student was looking at a model of dinosaur teeth. “These teeth might come loose,” he told one of the teachers. “They’re like my teeth.” He opened his mouth and pointed to his own teeth. During the animal-themed week of the program, another student was touching animal furs at a table while her class was taking turns walking through the Live Animal Care Center. She stroked a skunk fur and said, “That’s a skunk; you have to take a bath in tomato juice,” making a connection to the experience of being sprayed by a skunk.

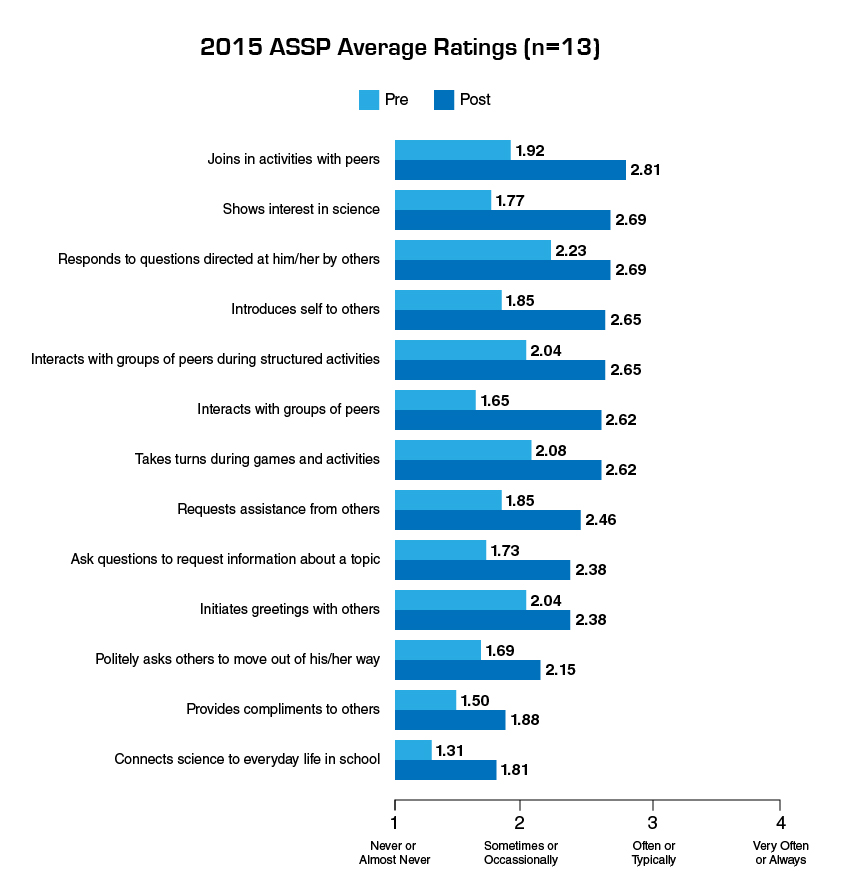

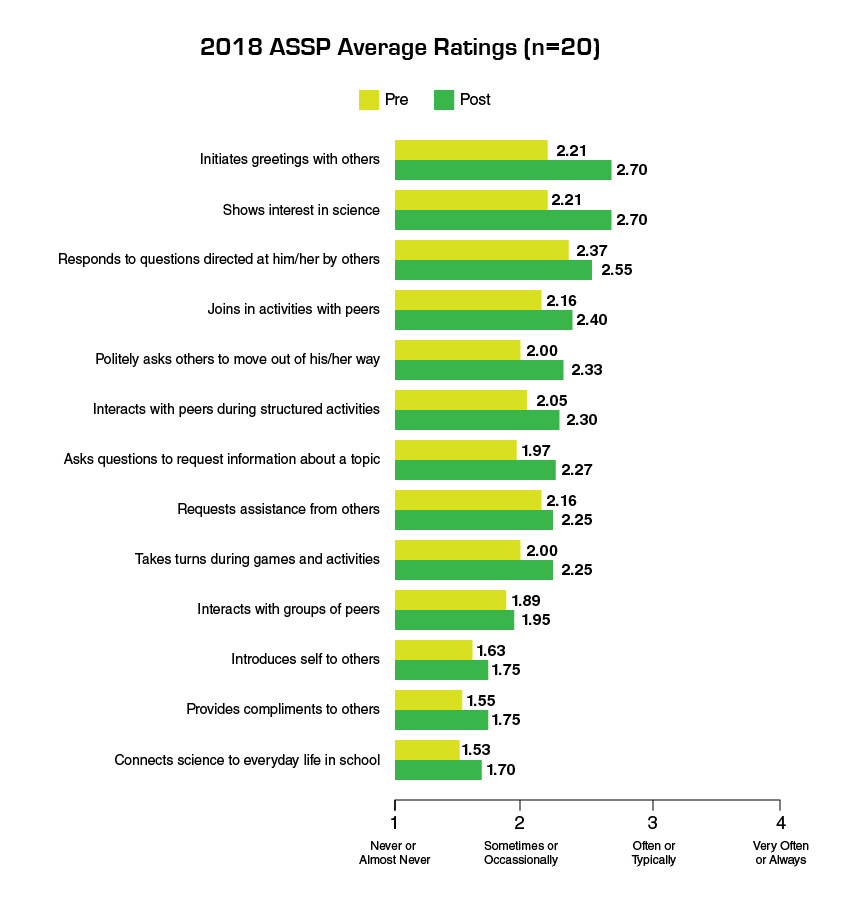

In 2015 and 2018 BPS teachers were asked to provide an assessment of their students’ observed behaviors before and after the BEST Program. The assessment included behaviors such as how much interest a student shows in science, how the student connects science to everyday life, and social participation (such as joining in an activity with peers or taking turns). Teachers assessed students’ social behavior by completing a pre-post survey that was adapted from the Autism Social Skills Profile (ASSP), a standardized measure of social functioning for children with ASD (Bellini and Hopf 2007). The ASSP behavioral item list was adapted to include the social behaviors most likely to occur during the BEST Program. In addition, two behaviors related to science engagement (i.e., shows interest in science, connects science to everyday life in school) were added to the measure. Students’ behaviors are scored on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 indicating “never” or “almost never” exhibits the skill or behavior, and 4 indicating “very often” or “always” exhibits the skill or behavior. In 2015 the ratings on all the social behaviors measured by the adapted ASSP averaged higher after participation in the BEST Program than before the program (see Figures 1 and 2).

These findings held true in 2018 for all the same behaviors that were measured in 2015—average ratings for all social behaviors measured by the adapted ASSP were higher after the program. In particular, in 2018 average teacher ratings showed the biggest change for students showing interest in science and initiating greetings with others. Average teacher ratings also increased for students connecting science to everyday life in school. Teachers also reported that their students were engaging in social and science-related behaviors more often after participating in the BEST Program.

Students themselves also reflected on their museum experiences toward the end of each field trip. During every MOS visit, following all the museum activities, the BU OT graduate students engaged the BPS students in a brief activity to support them in reflecting on the goals they had set for the visit and their sense of belonging at the MOS that day. This reflection was scaffolded with visual images of the students’ goals. The students either pointed to the image that portrayed their performance or used the visual cue to discuss their performance and perspective of belonging at the MOS. In 2015 students’ ratings for statements such as “I like science” and “I think about science when I’m not in school” both averaged at least 3 on a 4-point scale, where a 1 represented “disagree a lot” and 4 represented “agree a lot.” In 2018 the reflection changed to yes or no rather than a 4-point scale. Students answered “yes” or “no” to four statements:

- “I felt like I got along with others at the museum.”

- “I felt like I was part of the group.”

- “I liked the way I interacted with the group.”

- “I liked what we did at the museum.”

Across the six weeks, the number of “no” answers from students steadily decreased, from five “no” answers in week 1 to just one “no” on one of the four statements in week 6. Students’ positive feelings about museum activities and their social interactions appeared to increase as the program progressed.

Essential elements

The BEST Program is particularly unique in that it benefits not only the visiting students, but all members of the BEST Program partnership. While the students with ASD are able to visit a museum, the OT graduate students are learning the value of engaging youth with ASD in community-based contexts and how to support them in doing so. Museum staff have the opportunity to gain experience in working with and developing programs for students with ASD, while K–12 professionals gain confidence in bringing their students on successful field trips.

The BEST Program can help inform best practices in informal science education, as well as be an example for similar partnerships in other communities. As every community has differing needs, community partnerships may implement such a program in modified ways. However, the essential elements of the BEST Program are as follows:

- The program consists of at least four consecutive trips to the museum/science center to increase comfort levels, provide consistency and predictability, and encourage a sense of community belonging for the student participants.

- The program is implemented by a museum/science center in partnership with a college or university OT program and K–12 education professionals to collaboratively design student experiences focusing on both science and social goals.

- Students visit during regular museum/science center operating hours, integrated alongside typical visitors and participating—with support—in the general museum community whenever possible.

- Students engage in goal-setting and view customized social stories prior to each museum/science center visit, which help students anticipate and prepare for their visit.

- Given the resources and interactive features of museum/science center exhibits, activities are carefully designed to facilitate science learning and social interaction.

- Students engage in reflection on their performance and goal achievement following each visit to the museum/science center.

The BEST Program shows that with care and collaboration, students with ASD can be supported inclusively in informal learning settings and benefit from such inclusion. Additionally, it demonstrates how a thoughtful partnership between multiple institutions can creatively address the needs of underserved students in their shared community. The BEST Program is a demonstrably successful approach for communities looking to support students with ASD in science engagement and social participation.

Katie Slivensky (kslivensky@mos.org) is the school and youth programs coordinator at the Museum of Science, Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts. Ellen Cohn (ecohn@bu.edu) is a clinical professor and the entry-level OTD program director in the Dept of Occupational Therapy in the Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Boston University in Boston, Massachusetts. Alexander Lussenhop (alussenhop@mos.org) is a research associate at the Museum of Science, Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts. Christina Moscat (cmoscat@mos.org) is the program manager of school and youth programs at the Museum of Science, Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts.

citation: Slivensky, K., E. Cohn, A. Lussenhop, and C. Moscat. 2019. The BEST partnership program: Supporting students with ASD by Connecting schools, museums, and occupational therapy practitioners. Connected Science Learning 1 (10). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-april-june-2019/best-partnership-program

Disabilities Informal Education