feature

Teaching Sciences With Impact Using the Lectorial Approach: Stimulating Active Learning

Journal of College Science Teaching—September/October 2020 (Volume 50, Issue 1)

By Jyothi Thalluri and Joy Penman

This article reports on students’ experiences of the lectorial approach that was implemented for health science students studying sciences at a South Australian university. A lectorial, based on active student-centered learning, is a newly-designed teaching method for a large-scale class employing interactive activities to enhance student engagement. Students prepare for lectorials through conceptual-based, prerecorded lectures and online materials and identify aspects that need further clarification. During the lectorial, students have opportunities to think critically, reason, and solve problems. Students were asked to complete a questionnaire on the lectorial and how it impacted them. The results indicated that the students valued the lectorial approach, as it helped them to learn and understand the course content better and maintain their interest and attention. The lectorial-style presentation provided opportunities for connection, relevance, and active learning. Students recommended it for this course and other courses, as well as for future students.

A large, comprehensive meta-analysis of undergraduate science, engineering, and mathematics courses conducted in 2014 (Freeman et al., 2014) reveals an improvement in mean examination scores with active learning sections, with students taught traditionally more likely to fail in comparison. Others have also demonstrated a preference for teaching that involves active learning rather than traditional lectures (Cavanagh, 2011; Geven & Attard, 2012; Zain et al., 2012).

While questions have long been raised regarding the continued use of traditional lecturing, new developments in higher education have necessitated significant changes in teaching methods. Attendance and participation during contact times have been declining (Dolnicar et al., 2009). There is also the need to increase learner engagement with content, peers, and staff via interaction and feedback.

In the health-related disciplines it is essential to provide learning activities that connect sciences to the health professions and place science content into clinical contexts, providing opportunities for e-learning, workplace learning, and lifelong learning. Furthermore, it is important to make learning sciences enjoyable, engaging, and exciting for university students (Zain et al., 2012; McCabe & O’Connor, 2014).

In response to these new developments, universities invest heavily in educational frameworks that support the strong interrelationships between preclass, in-class, and postclass activities. In particular, our response has been to adopt and introduce the lectorial. A lectorial is a combination of lecture and tutorial teaching modes designed to improve opportunities for student engagement in larger cohorts (De la Harpe & Prentice, 2011). It is a newly designed teaching approach employing interactive, inquiry-based, and active student-centered learning (Thalluri & Penman, 2017; Slattery et al., 2018; Thalluri & Penman, 2018). This approach shifts the learning responsibility from the teacher to the learner as it requires the learners to be prepared for class and to be actively engaged with the learning. The lectorial approach used has been modified from the educational method trialed at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) by de la Harpe and Prentice (2011).

This article reports on a quantitative study on the lectorial teaching methodology conducted in 2016 and 2017 by means of a survey in each of those years administered toward the end of a science course, Human Body 1. It examines aspects of the lectorial that students found useful for their study of the course. First, however, is an exploration of active learning and the lectorial approach. Second is a scrutiny of the role that the lectorial played in the study of the human body and a comparison between traditional lectures and lectorials. Finally, suggestions for improvement are also discussed.

Background

Active learning is an educational approach in which learners engage with the material they study, achieved through the fundamental processes of reading, writing, discussing, and reflecting (Khan et al., 2017). In comparison with other teaching methods, the learners are active participants in the learning process (Braungart et al., 2019), and the teachers are facilitators of learning, referred to as “guides on the side” (Nichols, 2016). Students are engaged inside and outside the class, and are challenged to think more actively and creatively for themselves and not to rely on the “sage on the stage” (Berner, 2004; Nichols, 2016). They are involved in interactive and collaborative activities, which encourage them to maximize their learning, continue their studies, achieve their full potential, and experience the reality of the workplace vicariously (Penman & Thalluri, 2012).

The overall quality of the teaching and learning experience is enhanced with active learning. Those golden opportunities of learning how to frame questions, confirm understandings, clarify doubts, and apply and consolidate new knowledge are essential for deep and meaningful learning (Freeman et al., 2014). In active learning, opportunities are created for the construction of knowledge through analysis and evaluation, manipulation of the environment, and authentic, goal-directed activities that motivate thinking. In short, learners take charge of their learning (Baetena et al., 2013; Roach, 2014; Carroll & Dunne, 2016).

In incorporating active learning principles into the learning process, the lectorial accomplishes the creation and acquisition of knowledge. It encompasses a variety of teaching strategies, such as problem-based learning, case-based learning, inquiry-based learning, and technology-assisted learning, to name a few (Evans et al., 2014). Learners interact with the course material through carefully designed activities, such as quizzes, group discussions, and case studies. These activities help learners develop critical-thinking and problem-solving skills, facilitate acquisition and retention of knowledge, increase motivation, and enhance communication and interpersonal skills. The learners are the focus of the learning experience (Kim et al., 2013). The concept of student-centered learning is closely related to active learning.

Student-centered learning has figured prominently in higher education in recent years (Geven & Attard, 2012). It has been associated with the principles of constructivism, incorporating prior knowledge, active learning, and sense-making (Cavanagh, 2011; Tangney, 2014). It is distinguished from traditional approaches as it encourages the learners to take on the responsibility for their learning, resonating closely with active learning (McCabe & O’Connor, 2014). A quantitative study of Malaysian students demonstrated that learning skills in student-centered learning are through students’ heightened interaction and cooperation, inside and outside of the classroom. Students were active learners, more responsive, and able to relate to their experiences (Zain et al., 2012).

The study on which this paper focuses will determine whether the lectorial can provide active and student-centered learning.

The lectorial approach

This section describes the lectorial approach used in a science course for nursing and midwifery students. The overarching aim of implementing the lectorial was to improve the education and experience of health science students in Human Body 1, a first-year science course. The specific objectives include: increase student engagement with content, peers, and staff; identify concepts students struggle with after self-study and address student-generated questions; motivate and inspire undergraduate students to study sciences through relevance; and manage the learning of a large cohort of students (Thalluri & Penman, 2017). A conceptual model, adapted from Pathak (2020), summarizes the essential steps of the lectorial approach (see Figure 1).

Lectorial model of teaching and learning.

Initiating (step 1) involves rich learning situations that start with conceptual-based, prerecorded, short, motivating lectures prepared by the lecturer (from 7 to 20 minutes in length), followed by online, self-driven preparation before the lectorial session. The assessing phase (step 2) covers self-assessment quizzes that test students’ understanding of the content and identify aspects that are clear or unclear to them. Hence, the learners come to step 3 knowing which aspects they wish to clarify (Czaplinski et al., 2016). Step 2 requires students to identify areas of full understanding and areas of difficulty. Students determine what they know, what they do not know so well, or what they do not know at all before the lectorial.

Step 3 is executing, which represents the interactions during the lectorial. Case studies based on authentic workplace experiences are presented, and students are fully immersed and actively engaged in learning situations that challenge their problem-solving and critical thinking and reasoning skills (e.g., determining a problem, exploring alternatives, solving problems, suggesting interventions, and evaluating interventions). Monitoring (step 4) pertains to the online summative (graded) assessments on each topic that also help with the exam revision. Other collaborative and interactive activities are used to expand on concepts and broaden understanding. The final teaching activity is closing (step 5), which is about reflection and application, where the student can internalize the content and link the learning to clinical contexts and how the same might impact on their practice. The lectorial is also recorded, allowing students unable to attend class to watch it at their own time and pace, and answer questions posed by the lecturer.

The approach also entails a physical environment complete with multi-media and good acoustic design (de la Harpe & Prentice, 2011). Various learning facilities and spaces were used for the lectorial. Enhanced technology to increase active learning was employed. A conducive learning environment was paramount, one ideal for small- and large-group discussions and interactions. Other spaces, such as course websites (Moodle), e-readings, and online discussion groups were also used. The success of the lectorial also depended on the technical staff working behind the scenes who monitored and maintained the university computer systems, networks, and software.

During the lectorial, various learning environments were incorporated for integrative, collaborative, and reflective purposes. Lectorial exercises included the extended multiple-choice questions about the week’s topic administered before the lectorial, and the exercises during the lectorial included activities such as mind-mapping, completing tables and diagrams, problem-solving case scenarios, small-/large-group discussion, and games. In addition to computers and laptops, smartphones were also used. Software such as Socrative was used. Socrative allows teachers to create quizzes for students to take promptly on their laptops, tablet computers, or smartphones (Kirkwood & Price, 2014). Results can be displayed on the screen, providing immediate feedback.

Methodology

Research sample

Of 1,033 nursing and midwifery Human Body 1 students enrolled at a South Australian university in 2016 and 2017, 392 (148 in 2016; 244 in 2017) replied, for a 38% response rate. The evaluation was conducted within three weeks of the conclusion of each course.

Research design

Surveys were used to evaluate the impact of the lectorial. Using a questionnaire, data about the participants’ knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about the lectorial approach to teaching were collected.

Methods of data collection

Students were requested to complete a 20-item questionnaire consisting of closed and open-ended questions (see https://www.nsta.org/college/connections.aspx). The questionnaire had Likert-type questions where students were asked to select their choices from predetermined answers, to agree or disagree on statements, and grade the frequency of occurrences as always or never, at various levels. The questions pertained mainly to students’ experiences with the lectorial. Briefly, students were categorized as school leavers (those who had just completed year 12 of school) or mature-aged students (nonschool leavers and over 21 years old) (question [Q] 1); other questions covered: listening to and watching prerecorded lectures before the lectorials (Q2); experience with prerecorded lectures essential for making the lectorial a good learning experience (Q3); putting content into context (Q4); learning and comprehending the material (Q5); connection of activities (Q6); impact on interest and motivation (Q7); preference of approach (Q8–11); boredom level (Q12 and 13); relevance of the lectorial (Q14 and 15); comparison with other methods (Q16); open-text response on how the lectorial was different from traditional lectures (Q17); and strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations (Q18–20).

Methods for data analysis

A descriptive quantitative analysis was performed. “Preidentified classification” to categorize observations was used (Shields & Smyth, 2016, p. 148). This enabled the collection of information about the characteristics and/or perceptions of the participants about the lectorial. Counting and reporting the frequency of concepts, words, and descriptions mentioned in the data were undertaken (Creswell, 2003; Vaismoradi et al., 2013; Fisher & Fethney, 2016). The frequencies of responses were summarized and reported in tables.

Ethical considerations

Approval for the study was sought and obtained from the university ethics committee.

Limitations of the study

Results were constrained by several limitations, including the lack of a control group and the modest response rate.

Results

Following is a summary of the results obtained from the 392 students who responded to the survey. Results showed that 65% of the survey respondents were mature-aged students (Q1). Ninety-four point seven percent of the students listened to and watched the prerecorded lectures before the lectorial in real-time or recorded version (Q2). Also, 98% of students agreed or strongly agreed that listening to the prerecorded lectures was essential for their learning (Q3). Ninety-eight percent of students believed that the lectorial content placed the science content into clinical context. This helped students see the relevance between science and nursing practice (Q4). Ninety-seven and 98% of students either agreed or strongly agreed that watching the prerecorded lectures prior to the lectorials gave them time to learn and comprehend (Q5) and connect (Q6) with the content. Ninety-three percent of students agreed or strongly agreed that the case studies used in the lectorial helped them become interested in the topic (Q7).

When asked about preference of teaching style, results showed that students preferred lectorials over the traditional and online styles (Q8) (see Table 1). Further results revealed that 88.3% of students wanted the use of the lectorial for all of the topics in the Human Body 1 course (Q9) and 73.7% students wanted lectorials for all courses in their program (Q10), while 93% of students recommended the lectorials for future Human Body 1 students (Q11). As previously reported (Thalluri & Penman, 2017), 53% of participants rated traditional lectures as boring and extremely boring, while only 16% judged the lectorial as boring (Q12 and Q13). Furthermore, 98.1% of respondents “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that the lectorial facilitated putting course content into context (Q14), and that it boosted 92.5% of students’ interest by illustrating clinical relevancy of the anatomy and physiology in the course (Q15).

| Table 1. Student preference of teaching method. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

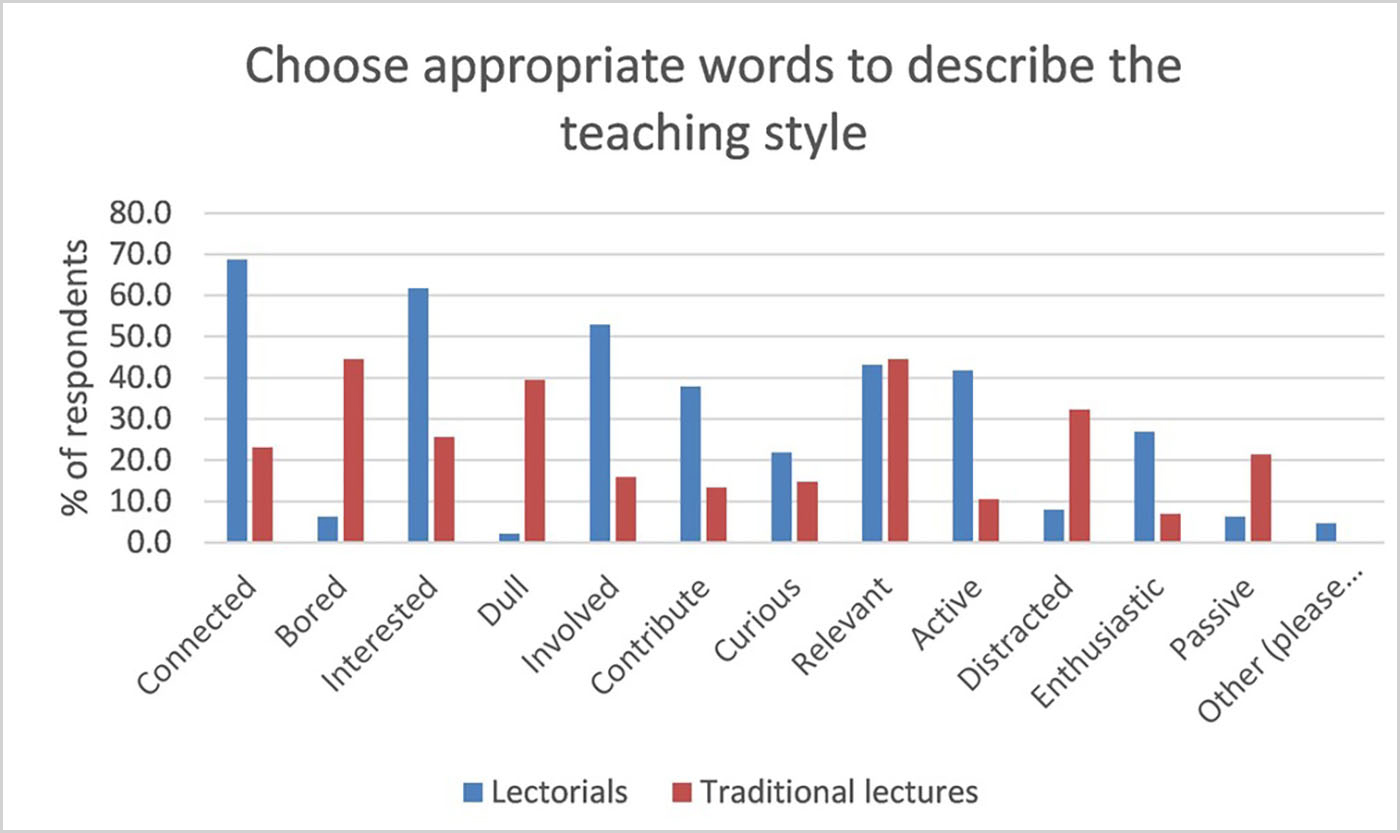

Students described the lectorial with the following terms: connected, interested, involved, relevant, and active (see Figure 2). These were the most popular terms that aptly described the lectorial from the respondents’ point of view.

Students’ descriptions of the lectorial.

Table 2 compares and contrasts traditional lectures and lectorials (Q17).

| Table 2. Comparison between traditional lecture and lectorial. | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There were many reasons why the respondents liked the lectorial approach, and some of these are tabulated in Table 3 (Q18).

| Table 3. Reasons for approval of lectorials. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

When asked to suggest how the lectorial style of delivery might be improved, Student #52 (2017) articulated his/her response well by saying: I think there is still a lack of involvement amongst young people at university. They are so self-conscious and worried about being wrong. Maybe a preparatory? talk before the lectorial to explain that participation and involvement results in learning and retention of information and that it is okay to be wrong. You learn from your mistakes. I also think problem-based learning would be beneficial. Perhaps a case study could be given in the prerecorded lectures. Symptoms are presented, and it is the student’s job to problem-solve.

Discussion

The lectorial was identified as providing many learning benefits to students who were placed in an environment that helped them comprehend and apply science concepts, motivated them to learn actively, and provided ongoing feedback and engagement. The majority of students not only approved its use, but they also preferred it over traditional lectures and recommended it to other students. Students described the lectorial as assisting them to be connected, interested, involved, and active. Moreover, they found the lectorial to be relevant to their nursing profession. All of these descriptors also point to active learning and student-centered learning (McCabe & O’Connor, 2014).

Assisting students to be connected, interested, involved, and active

There was a strong connection between the lecture and the lectorial. The lectorial strengthened the connections between the preclass, in-class, and postclass activities, linking the learning together. More than connection of structure and activities, the connection was from the “theory to a real-life scenario,” which was synonymous with bridging the theory-practice gap (West et al., 2012). This connection promoted the principle of student-centered learning emphasizing discovery of information, analysis, and problem-solving. Students made sense of the learning; the lectorial provided students focused attention, helped construct knowledge, and facilitated collaboration with others (Watkins et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013). The activities kept students interested and motivated about the content, and with interest and focus came the desire to be involved and to actively participate in the activities. This was essential because the best way to learn is by participation (Braungart et al., 2019). Additionally, there was also reduced boredom and distraction in lectorials, enhanced engagement and learning, and improved student attendance. A case in point was a student’s comment (Student # 109, 2016), stating, “Lectorials are more active, fun and we also contribute and get involved in various activities which help us understand the topics in more depth.” It helped engage students with the content, peers, and staff members, and made learning fun and enjoyable.

Relevant to the profession

Students highlighted the focus of relevance in the lectorial as the content was placed into clinical context and the nursing profession. The case studies provided opportunities to explore authentic cases that required putting the science content into clinical context. Theory was integrated with practice. Students could see its applicability, and this increased their interest, stimulated critical thinking, provided a guide to problem-solving, prepared them for practice, and increased their confidence. With understanding comes retention of information (Evans et al., 2014).

Active learning

The lectorials were found to encourage active learning. Students were not passively learning (just sitting and listening); they participated and paid attention, achieved in student-centered learning, according to Zain et al. (2012). They were actively learning. They became interested, and they discussed and learned about the topic with more depth. Students became self-directed learners, identifying the areas in which they needed more understanding or clarification. They interacted with others in the process, became more enthused to learn, and had fun in the process.

Implications

The study has implications for teaching practice and future research. The findings could inform and change future pedagogical approaches to the study of sciences, providing opportunities for students to explore, analyze, clarify, question, collaborate, evaluate, and reflect on the topics through the lectorial approach. More than recall and comprehension, students used higher levels of thinking, such as problem-solving activities, critical thinking, and discovery learning in which learners are presented with authentic contexts (Bastable & Quigley, 2019).

The above lectorial approaches helped with summative (graded) assessments. Evidence of this assertion was drawn from anecdotal reports, including student #61 (2016) who remarked that the lectorial was “more interactive. Activities help with my summative assessments.”

The average final exam mark for 2014 and 2015 (prior to introducing the lectorial style) was 4% lower than in 2016 and 2017 (after introducing the lectorial style teaching) (59% and 63%) for Human Body 1 course.

Future research will focus on considering a control group, and adding more clinical cases, continuing rigorous evaluation, including long-term impact, promotion to other staff, and dissemination of findings.

Conclusion

There is very little literature on the lectorial, a blended learning activity. This study uses a satisfaction survey postdesign to establish an understanding of the role of the lectorial in teaching and learning a science course. The findings in this study suggest that hallmarks that distinguished the lectorial were connection, interest, involvement, relevance, and active learning.

Learner experience has been a central consideration of the course development process. The respondents’ experience with the lectorial approach has been positive, maximizing multiple opportunities for encounters with course content and feedback opportunities, as well as facilitating active learning and clinical relevance. The lectorial is recommended for implementation in the health sciences course for students at the university.

Jyothi Thalluri (jyothi.thalluri@unisa.edu.au) is a senior lecturer at the University of South Australia in Adelaide, Australia. Joy Penman is a senior lecturer at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Learning Progression Teaching Strategies Postsecondary