Elementary | Daily Do

How Do We Cross Bodies of Water?

Careers Crosscutting Concepts Engineering Is Lesson Plan Literacy Science and Engineering Practices Elementary

Welcome to NSTA's Daily Do

Teachers and families across the country are facing a new reality of providing opportunities for students to do science through distance and home learning. The Daily Do is one of the ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families with this endeavor. Each weekday, NSTA will share a sensemaking task teachers and families can use to engage their students in authentic, relevant science learning. We encourage families to make time for family science learning (science is a social process!) and are dedicated to helping students and their families find balance between learning science and the day-to-day responsibilities they have to stay healthy and safe.

Interested in learning about other ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families? Visit the NSTA homepage.

What Is Sensemaking?

Sensemaking is actively trying to figure out how the world works (science) or how to design solutions to problems (engineering). Students do science and engineering through the science and engineering practices. Engaging in these practices necessitates that students be part of a learning community to be able to share ideas, evaluate competing ideas, give and receive critique, and reach consensus. Whether this community of learners is made up of classmates or family members, students and adults build and refine science and engineering knowledge together.

Today's Daily Do: Sensemaking Tasks for K-2 and 3-5 Students

Today's Daily Do presents two different—but related—science tasks centered around children's books.

- What Floats in a Moat? (K–2) Students float and sink everyday objects to figure out what makes some things float and other things sink.

- Who Sank the Boat? (3–5) Through an engineering design challenge using aluminum foil and pennies, students figure out how the shape of a boat and its ability to float are related.

Although designed for different grade levels, you may choose to do both tasks with your K–5 students (you can adjust the amount of scaffolding in both tasks). Make sure to check out information on the STEM careers at the end of this Daily Do: Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering!

Introduction to Early Childhood (K-2) Science Task

Young children ask “why” often. They are curious. They wonder. They ask questions about all things around them. Encouraging elementary-aged children to explore the world helps them develop not only an understanding of how things work, but also self-confidence. This Daily Do focuses on using a piece of children’s literature as the starting point for the focus question “How Do We Cross Bodies of Water?”, which includes discussions around floating, sinking, and displacement. Using picture books with children can also help them develop their reading skills while they are investigating science topics, and provides a common experience for both the adults and children to discuss.

Children may experience sinking and floating in various ways: playing with bathtub toys, throwing rocks in a pond, or watching boats. Asking them to consider what properties objects have that make them float and sink helps them to start to connect the ideas to the practice of “asking questions and defining problems.” Through the use of everyday objects found around the house, parents can help children “plan and carry out investigations,” as well as engage in the engineering design process as they explore answers to their questions.

This investigation uses the book What Floats in a Moat? Written by Lynne Berry, this book tells the story of two characters named Archie the Goat and Skinny the Hen. Archie and Skinny are attempting to deliver barrels of buttermilk to the queen when they encounter a moat that must be crossed to make the delivery. Rather than taking the drawbridge, “this is a time for science,” Archie explains, and the two undertake a series of trials to determine if a barrel sinks or floats. Listen to the book read aloud here.

Before Listening to the Read-Aloud

Gather a few objects from the house and yard such as a rock, a bath toy, a metal key, a spoon, and other objects, making sure that you have some that sink and some that float. Include two 12-oz. cans of the same type of soda (not diet). Print a copy of the KLEWS Chart, or display a copy.

Introduce the Question and Elicit Initial Understanding

| Figure 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Share the photo with the students and involve them in a conversation with the following questions:

- Can you tell me about why some things float and why some things sink?

-

Where have you seen things float?

-

Have you tried to make an object float?

-

What did you do? What happened?

-

Have you ever tried to cross a river or lake or pool or seen people or things crossing bodies of water?

-

What did you do to cross besides swim? What have you seen others do?

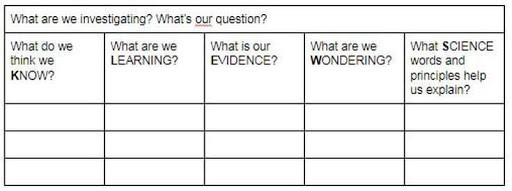

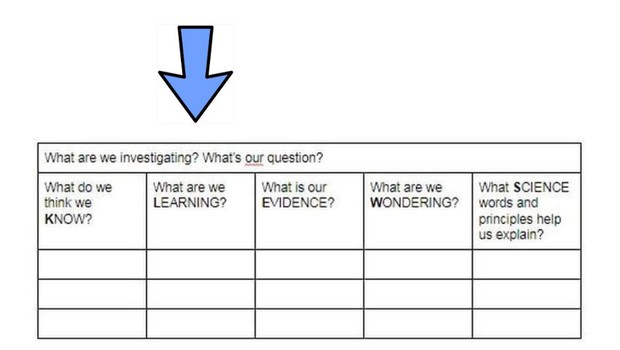

As students respond to the questions, help them fill in the information for the KLEWS chart under the first column, "What do we think we know?"

(A KLEWS chart is a table that allows students and teachers/parents to organize their thinking. The letters in KLEWS stand for Know, Learning, Evidence, Wondering, and Science [for words and principles].) For more information about this strategy, click here.

Share with students that knowing about floating and sinking helps us in many ways, such as when we need to cross a river or an ocean. Let them know they will now explore this question: What are ways to cross bodies of water?

This is the driving question to put into the KLEWS chart.

Connect the Children’s Literature

Show children the cover of the book What Floats in a Moat? and ask them to consider how this story connects to the question about crossing water barriers. Read or share the recording of the book with the child. Pause at various points to ask the children the following questions:

-

What is the problem that Archie and Skinny must overcome? (Pause at :30 seconds)

-

What does Archie want to do to cross the moat? What does Skinny want to do? (Pause at 1:13)

-

What science does Archie need to know to solve this problem? What did Archie do to use “science” to solve his problem? (Pause at 1:50)

-

What are changes that Archie makes to the barrel each time to see if it will float and help him cross the moat? (Pause at the following times: 3:34, 6:20, 7:56)

-

How does Archie change the barrel of buttermilk to solve his problem to cross the moat with the barrel? (9:23, at the end)

After discussing the above questions, help the students summarize what the characters were doing for each launch attempt (changing the amount of buttermilk in the barrel). These questions will allow the children to first identify the problem (how to cross the moat), recognize one solution to that problem (using the drawbridge), and identify that Archie will need to use an engineering design process (see the Extending the Learning Section) to solve the problem in a different way (because he didn’t want to use the drawbridge). This book also allows students to make connections to their own world and engage in sensemaking.

One way to make the book more meaningful to students is to help them connect it to their own world. This can be done using a strategy called text to world connections, in which the reader or adult models and then asks the children to connect the story text to larger experiences in the world that they may have had. In this case, it engages the children in identifying what the problem is in the story and how others have accomplished the challenge of crossing a body of water.

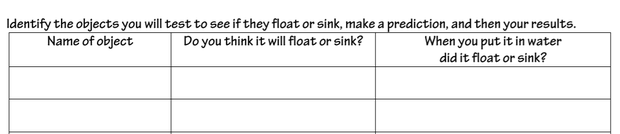

Predict

Using the different objects that you gathered, ask the students to make predictions about each and state whether it will float or sink. Wait until the very last object has been discussed to use the can of soda (not a diet soda) as an object. You will need two cans of the same type of soda to do this investigation. Have the children explain why they think something will sink or float in the moat as you create a list of possible reasons.

Explore

Tell the children that this is a time for discoveries similar to what Archie said in the story, and they will test what floats just as Archie and Skinny did. Fill either a basin or kitchen sink with water, then model how they will test each object by placing it in the basin or sink. An example of an item that can be used is a metal key.

Ask: "If I were to drop this key into the water, what do you think you will observe? Do you think it will sink or float?" Ask them to explain their prediction, which may include answers such as “I’ve dropped something like it in the water before”; “It’s heavy, it’s light”; etc. Help the children record their prediction on their observation sheet. After testing the object, model how children should record their observation on the data sheet. Allow them to continue to test the different objects.

-

Pick up the can of soda again and ask the students to describe what happened when the can was placed in the water (the can sank).

-

Now empty the can of soda and place it in the basin/sink and discuss what happens. Ask students to describe the difference between the two cans when placed in the water? How does this connect to the empty barrel in the story?

-

What do you think we need to do to make the can, like Archie’s barrel, sink and float like in the story?

-

Guide the students to the answer that they need to empty about ½ the can of soda and explain their reason.

Discuss

It is possible the children will find that some objects do not float to the top and do not sink to the bottom. Ask them to describe their observations and engage in a conversation about the definition of floating and sinking.

In What Floats in a Moat?, the empty barrel and the half empty barrel both floated. However, one did not displace as much water and did not “sink” as far as the half-empty barrel. As you move through the prompts below, ask students in what ways the soda can behaved like the barrel.

Reflecting on what you did with the soda can, discuss the following:

-

When the barrel was full, what happened when Archie tried to use it to cross the moat? (It sank.)

-

When Archie tried again, he used an empty barrel. What happened with the empty barrel? (It floated on top of the water, but was not a good boat.)

-

Why do you think the third try of using a barrel to cross the moat worked? (It neither floated on top of the water, nor sank to the bottom; the buttermilk added some weight to stabilize the boat).

After discussing what happened with the soda can when filled to different amounts, have students add what they learned in the column in the KLEWS chart and the evidence to support their learning.

Consider

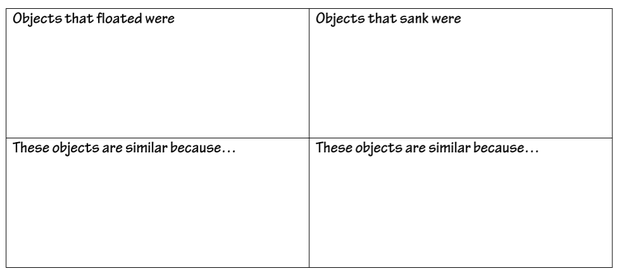

Now ask the students to separate the objects into two piles—objects that floated and ones that sank—and then make observations about the two piles and record them on their observation sheet.

Ask: What are common characteristics of the objects in each pile? Many children will make generalizations about the objects, such as wooden objects tend to float and metal objects tend to sink, which is appropriate for this age level. One statement that may be made and is partially correct is “heavier objects sink” and “light objects float.”

Looping Back

Ask them to select one item for which the outcome was different from their prediction, and ask them to complete the following prompt:

Revisit the KLEWS chart and fill in the other columns together. Encourage them to provide evidence for what they claim they are learning. Record new things they are wondering about that could be the starting point for new explorations. (Refer to the science concepts section below only as background information for you.) In the last column of the KLEWS chart, K–2 students will and should be focused on the properties of the objects that sank and float.

NGSS PS1.A: Structure and Properties of Matter (K–2)

Different kinds of matter exist, and many of them can be either solid or liquid, depending on temperature. Matter can be described and classified by its observable properties.

Science Concepts

This section is background information for the adult. The terms and concepts as written are not developmentally appropriate for introducing in grades K–2. The standard above is what is the expected level for the students at this grade range.

The main science concepts in this investigation are

-

Mass is the amount of matter in an object.

-

Solid objects will float or sink in water based on their density.

-

Objects have observable properties, such as mass and volume.

-

Volume is how much space an object takes up.

-

Density describes how much mass there is in a given volume.

How heavy or light the object feels is something that students will comment on as they discuss their groupings. The mass (kids will say weight) of an object is only one of the factors associated with sinking or floating. Return to the different parts in the book in which Skinny is trying to launch each barrel, and have them observe the illustrations in which Skinny is attempting to launch the full barrel, the empty barrel, and the half-full barrel. What do they notice about these attempts? The illustrations clearly show that Skinny has a harder time moving the full barrel because of the weight, and the empty barrel is much easier These illustrations—along with guiding questions such as “Do you think all of the barrels are heavy? What makes you think that?”—will assist in beginning this type of discussion. Most children will indicate that the barrels get lighter as the buttermilk is removed.

Helping students consider other properties of matter and how those properties affect the sinking and floating is the goal. To help students consider this, say, “But two barrels floated, one that was empty and one that was half full, so do you think there could be something else besides the weight of an object that helps things float or sink?” Most children will answer “yes,” but be unable to explain what that aspect may be, which is acceptable at this level. If necessary, refocus the discussion on the similarities of objects that floated and the similarities of objects that sank.

Introduction to the Elementary (3-5) Task

The investigation for the older students takes the idea of floating and sinking one step further and begins to consider how other variables helped Archie successfully cross the moat. Revisit Does It Float in a Moat? and ask children to look at the names of the “boat” that Archie uses when the barrel is empty, full, and half full, as well as where in the water the barrel sits.

When the barrel is full and sinks, he names the ship the SS Buttermilk. The empty barrel is called SS Empty and floated on top of the water, which is why it tipped and rolled. The half-full barrel is the SS Ballast and sinks some in the water, but floats and is stable. Ballast is defined as a heavy material such as sand or gravel or iron placed low in a ship that helps improve its stability. This is also demonstrated by observing the soda can with different amounts of soda in it.

Two ideas are presented at this next level: density and displacement of water. While calculating density is not done at the K–5 level within the Next Generation Science Standards, students are asked to continue to “make observations and measurements to identify materials based on their properties,” which can be done through participation in the series of activities and discussions. Students in grades 3–5 are also “Developing and Using Models” as they design and test their boats to determine which will float.

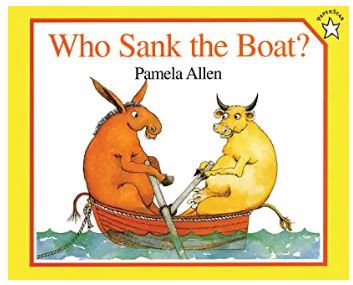

Before

Gather a basin for water, or plan on using the kitchen sink, tinfoil, and pennies or marbles. Print the student design sheet.

Elicit Student Understanding

Pose the following question: Why would a small pebble sink, but not a boat full of people? With each of the following questions, ask the students to make predictions about what would happen, and record their answers on the board.

- Would a penny sink or float? What about a half-filled plastic bottle? Explain your answer.

- Will a piece of aluminum foil that is a single sheet float or sink? What if that sheet was crushed into a very tight ball?

Remind children that Archie needed to keep his boat steady so that he could cross the moat. And then ask, “What if Archie had many friends who needed to cross the moat with him? Do you think the boat would still float in the moat?

Connect the Children’s Literature

Share with students a new book titled Who Sank the Boat? by Pamela Allen. In this book, a group of animal friends decide to go for a row in a boat. The animals jump one by one into the small boat. Before each animal jumps, readers are asked: “Do you know who sank the boat?” Cow, the heaviest, is first to go. The boat is unbalanced and low in the water, but it doesn’t sink. With each animal, the boat gets lower in the water. Little mouse, the lightest, is last to go. He jumps in, the boat sinks, and the story ends with “You do know who sank the boat.”

When presented as an introduction to hands-on explorations, this book can help teachers pre-assess students’ knowledge and determine if they have misconceptions about the topic. For example, many students believe that all heavy things sink. An object’s shape, mass (as it impacts density), and the materials it is made from, as well as the number of passengers it holds, will affect whether a boat floats or sinks.

See the Extending the Learning Section to apply the engineering Design Process to the students boat design challenge.

Discuss

Ask students to examine where the boat “sits” or is visible above the water here. If you look closely, you can make out several rows of wood that make up the boat that are above the water. Now ask them to look at the next picture and observe how much of the boat “sits” or is visible above the water.

Ask: “How are these pictures similar to the story Who Sank the Boat? Discuss with the students that when a boat pushes down on the water, it moves the water out of the way or displaces it. The shape of a boat is an important factor to consider when building a boat. The number of people or the mass the boat needs to hold is another factor.

Explore

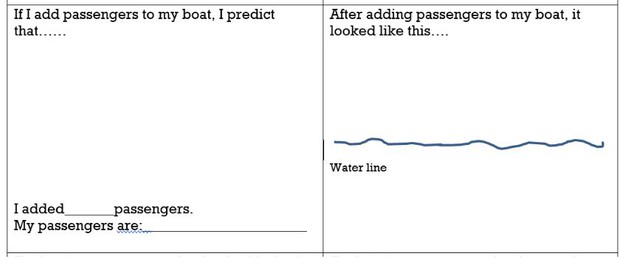

Draw the students back to their predictions for the piece of tinfoil noted above, and test the predictions and allow them to make observations of what happened. Using a sheet of tinfoil, challenge the students to create a boat that will be able to stay afloat. Using their student sheet, have them draw their boat shape and what it looks like when they test it in the water. Is it stable? Does it tip over? Does it float? Sink?

Challenge

Once they know the boat will float, ask them to test the ability of the boat to hold passengers. First place 5 pennies in the boat and observe. Then use 20 pennies in a boat, then 50 pennies in a boat. If pennies are not available, marbles or Lego blocks, or some type of small manipulative that is the same size may be used. Have them illustrate what happens for each try of the “passengers."

After gathering information and making observations, challenge the children once more. Ask them to design a boat that will hold 75 pennies (or other object). Allow the students time to create a shape, test it, and then modify the shape (see Extending the Learning to connect the Engineering Design Process). After a discussion that incorporates the concept that water can be displaced, allow them to test their designs. Discussion questions after students have moved through the design process would include these:

- Why did you choose the shape of the boat that you designed?

- How did you determine what size boat to make to hold more passengers?

- What changes did you make to your original design or additional designs and why?

Discuss

- Do you think all boats displace water at the same rate? (No, boat design is a factor. This can be observed by marking the side of the container with a marker before placing the boat in and after. The water level will rise slightly, similar to when you get into a bathtub.)

- What happened as you added pennies to the boat? (The boat would displace more water, and more of the boat would be beneath the surface of the water.)

- What other material could you use to make a boat? (Clay works well.) How would the new material change your design?

By allowing students to redesign their boat, they are provided with an opportunity to make observations, test variables, and consider properties of an object.

Looping Back

Return to the terms density and displacement. Ask students to use their boats and explain why a ball of foil or stick of clay would sink, but their boat would float. What happened to the water? How is this similar to what happened when using the tinfoil? If you did the first investigation with the soda can, how is it similar to that investigation? Ask the students to explain their reasoning through a sketch and explanation on their student data sheet.

Extending the Learning

As noted in the beginning, children are naturally curious. Curiosity allows for an opportunity to extend the learning around this topic. There are opportunities to extend the learning in a variety of ways.

-

You can learn about different types of boats.

-

You can watch boats on the water and make observations.

-

You can research together the work of boat design engineers and their role in designing technologies for water environments.

-

You can also trace the use of the Engineering Design Process in the story.

Below are two ways to extend the learning for this Daily Do.

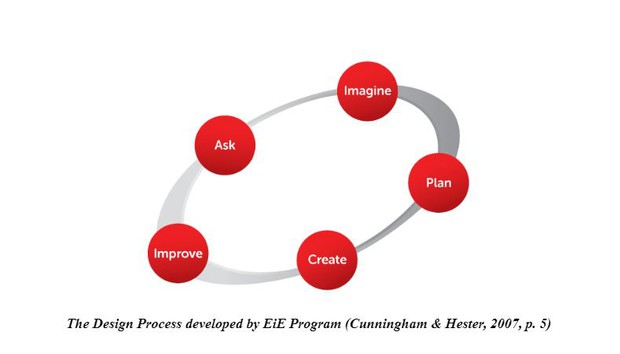

Engineering Design Process

The Engineering Design Process (EDP) comes in many forms. Engineers on the job may do the steps out of order, or skip a step, depending on the needs of a particular project. However, all the steps are important to good design. Below is a simple EDP for elementary students. There are as many variations of the model for all as there are engineers.

The Engineering Design Process engages the child in steps that help them focus on the task. These steps and examples from the story are

ASK. What is the problem? How have others approached it? What are your constraints? In the story, the problem was that Archie and Skinny needed to cross the moat.

IMAGINE. What are some solutions? Brainstorm ideas. Choose the best one. While Archie may not have chosen the easiest one that involved using the drawbridge, there were different solutions presented, including building a boat.

PLAN. Draw a diagram. Make lists of materials you will need. Archie demonstrated this by using materials, drawing, and sketching.

CREATE. Follow your plan and create something. Test it out! Archie built a boat and tested it out. It sank.

IMPROVE. What works? What doesn't? What could work better? Modify your design to make it better. Test it out! Archie continued to test the boat by changing a variable, which was the amount of buttermilk in the barrel.

Throughout the story, Archie is using an Engineering Design Process when he is applying science principles to solve his problem (the ask) of getting the barrel across the moat. Archie imagines, plans, creates, tests, and improves his model a few times.

Explore STEM Careers: What Do a Marine Design Engineer and Naval Architect Do?

Marine engineers and naval architects design, build, and maintain ships from aircraft carriers to submarines, from sailboats to tankers. Marine engineers are also known as marine design engineers or marine mechanical engineers, and are primarily responsible for the internal systems of a ship, such as propulsion, electrical, refrigeration, and steering. Naval architects are primarily responsible for ship design, including the form, structure, and stability of hulls.

STEM Career Awareness is an important part of educating and preparing our students for the future workforce. Students can explore the challenging and rewarding career of Marine Engineering by watching and discussing this video.

NSTA Collection of Resources for Today's Daily Do

NSTA has created a How do we cross bodies of water? collection of resources to support teachers and families using this Daily Do. If you're an NSTA member, you can add this collection to your library by clicking ADD TO MY LIBRARY, located near the top of the page (at right in the blue box).

Check Out Previous Daily Dos From NSTA

The NSTA Daily Do is an open educational resource (OER) and can be used by educators and families providing students distance and home science learning. Access the entire collection of NSTA Daily Dos.

Acknowledgments

This Daily Do has been modified by Christine Royce and Wendy Binder from the Teaching Through Trade Books column "Will It Sink or Will It Float?", which appeared in Science and Children in July 2014.