Table of Contents

If this issue had been published several years ago, the options for students to share their results would have been more limited. They could do “oral reports” to the class, a traditional science fair project, or the teacher could display their written work on the wall. These methods are still very good, and through technology students also have the means to share and get feedback on their work from around the world (Skype, blogs, webpages, social media, videos). But whether the sharing is high-tech or low-tech, the editor makes an excellent point …

your [the teacher’s]

challenge is to find outlets that offer appropriate sharing opportunities. Don’t assume students know how to do this. They must be taught how to organize their information and ideas in a variety of presentation formats. The articles in this issue present many ways for students to share, and I’ve noted the SciLinks topics that would support the content or that have suggestions for additional activities.

Two articles have ideas for tweaking the traditional science fairs to focus on communication.

Have a Kids Inquiry Conference describes an effort to provide students with an opportunity for students to share using a format that replicates a scientific conference, including discussion groups and poster sessions. The authors provide a sample schedule and suggestions for guiding students through the process.

A Standards-Based Science Fair puts the emphasis on the extent to which student project meet established standards or benchmarks rather than students competing against each other. The rubric (included with the article) guides students through the process of doing research. The author describes a scenario similar to the first article, in which the projects are displayed in the classrooms for visits by parents and other students. The projects are scored on how they meet the inquiry standards.

The guest editorial author, Linda Shore from the Exploratorium, describes

What a copper-plated nail taught me about sharing results. She notes how the experience could have been transformed from a demonstration to inquiry, with a little assistance from the teacher. On the other hand, the students whose explanations are showcased in

Explaining Electrical Circuits show a much deeper understanding of the concepts and vocabulary. The article describes how the teacher guided the students through the writing process (the rubric is included). [SciLinks:

Electricity,

Electric Current]

Who doesn’t like to talk about the weather? The first-grade

Weather Watchers use their senses and instruments to learn about the topic. I visited a school where the young meteorologists use data from their weather station to prepare a report each day that is read on the PA system and that the principal uses to decide on outdoor/indoor recess.

Delving into Disasters guides students through an investigation of weather data to find patterns and trends associated with rainfall and snowfall and with the paths of hurricanes. [SciLinks:

Weather,

What Is a Weather Map,

Weather Instruments,

Weather Forecasting,

Hurricanes,

Precipitation]

You can get some interesting discussions about what makes something “alive.”

Is It Living? includes an assessment probe to examine students’ preconceptions or misconceptions. In the activities described in

Living or Nonliving? students explore and discuss a concept that even older students struggle with. [SciLinks:

Living Things,

Characteristics of Living Things,

Life Cycles]

Sharing Digital Data takes a seed germination inquiry project to a new level by introducing fifth-grade students to online collaboration (secondary teachers take note). It’s fascinating to see how a traditional activity can be enhanced as students learn new skills (I hope the lead photograph was digitally manipulated and not a real situation). [SciLinks:

Seed Germination,

Plant Growth]

After reading

How does a lever work? you might be interested in helping your students learn more.

Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning shows how to use an investigation to help students communicate their conclusions in the form of a claim, evidence, and reasoning (not just with levers but with any topic). The article has an example of a document that guides student thinking, along with actual student work and how the rubric was used to assess it. [SciLinks:

Levers]

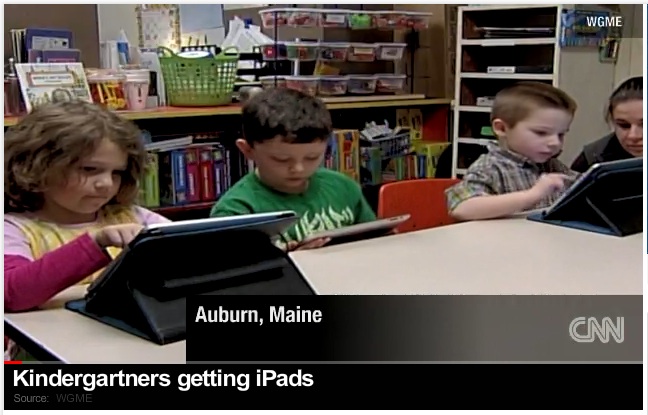

Kindergarten students are not too young to share their results! Young children love to play with play dough, and in

Sharing Research Results you can see what happens when they make their own. Note how the teacher guides them through using different ingredients and analyzing the results in a kid-friendly way.

All About Me/All About Gary young scientists use photography and journalism to explore their surroundings. I attended a photography seminar recently, and the questions that the teacher used with these young students were the same as we were asked in the seminar (Why did we take the picture? What does it say? What makes it interesting?).

And check out more

Connections for this issue (April 2011). Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, there are ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, and other resources.

Ammonia is one of the chemicals that feeds the world. No, you shouldn’t drink it from a bottle, and mixing it into your flan would be a bad idea, but about 83% of ammonia produced industrially is used as fertilizers, either as salts or as solutions, and it is estimated that fertilizer generated from ammonia sustains one-third of the Earth’s population, and that half of the protein the world eats grows from nitrogen produced from ammonia, while the remainder was produced by nitrogen fixing bacteria.

Ammonia is one of the chemicals that feeds the world. No, you shouldn’t drink it from a bottle, and mixing it into your flan would be a bad idea, but about 83% of ammonia produced industrially is used as fertilizers, either as salts or as solutions, and it is estimated that fertilizer generated from ammonia sustains one-third of the Earth’s population, and that half of the protein the world eats grows from nitrogen produced from ammonia, while the remainder was produced by nitrogen fixing bacteria.

I’m interested in finding some science assessments to supplement the state tests at the high school level. I’m especially looking for ones that will help me understand students’ thinking.

I’m interested in finding some science assessments to supplement the state tests at the high school level. I’m especially looking for ones that will help me understand students’ thinking.

Salads, sandwiches, and, of course, hamburgers feature condiments for flavor and texture. Tuna and chicken cling to onions and celery with the aid of mayonnaise. A teaspoon or so of mustard might add some bite to the salad. And if you’re feeling inventive, you could add a drop or two of hot sauce mixed with ketchup. How are these condiments made, and how do they manage to sit in the refrigerator door for so many months without breaking down into their constituent parts? Chemistry, my dear Ms. Child… chemistry.

Salads, sandwiches, and, of course, hamburgers feature condiments for flavor and texture. Tuna and chicken cling to onions and celery with the aid of mayonnaise. A teaspoon or so of mustard might add some bite to the salad. And if you’re feeling inventive, you could add a drop or two of hot sauce mixed with ketchup. How are these condiments made, and how do they manage to sit in the refrigerator door for so many months without breaking down into their constituent parts? Chemistry, my dear Ms. Child… chemistry.