An offer you can't refuse

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2010-03-12

The conference blog has reported on some interesting topics/conference events and sights to see in Philadelphia, but you’re disappointed that you won’t be able to attend this year—the economy, schedule conflicts, time constraints, etc. So here’s an offer you can’t refuse. I’m a “free agent” at the conference. Other than a few must-see general sessions, my schedule is open. So let me know via a comment if there is a hot topic in your school, with a brief context as to why it’s “hot.” I’ll be your avatar and attend some sessions on the topic. I’ll report back via the MsMentor blog after the conference.

The conference blog has reported on some interesting topics/conference events and sights to see in Philadelphia, but you’re disappointed that you won’t be able to attend this year—the economy, schedule conflicts, time constraints, etc. So here’s an offer you can’t refuse. I’m a “free agent” at the conference. Other than a few must-see general sessions, my schedule is open. So let me know via a comment if there is a hot topic in your school, with a brief context as to why it’s “hot.” I’ll be your avatar and attend some sessions on the topic. I’ll report back via the MsMentor blog after the conference.

I’ll even eat a Philly soft pretzel on your behalf!

The conference blog has reported on some interesting topics/conference events and sights to see in Philadelphia, but you’re disappointed that you won’t be able to attend this year—the economy, schedule conflicts, time constraints, etc. So here’s an offer you can’t refuse. I’m a “free agent” at the conference. Other than a few must-see general sessions, my schedule is open.

The conference blog has reported on some interesting topics/conference events and sights to see in Philadelphia, but you’re disappointed that you won’t be able to attend this year—the economy, schedule conflicts, time constraints, etc. So here’s an offer you can’t refuse. I’m a “free agent” at the conference. Other than a few must-see general sessions, my schedule is open.

Boost your meeting attendance

By Howard Wahlberg

Posted on 2010-03-12

Thanks to everyone who posted a comment and e-mailed me directly. Boosting meeting attendance seems to be on everyone’s mind. While there is usually no one “quick fix,” here are some ideas to think about:

- Restructure the meeting to appeal to a wider audience. Of course, you want programming to appeal to your most active attendees, but think about other attendees’ needs and other audiences.

- Use a marketing mix. Promote the conference via e-mail, your website (if you have one), in your newsletter, with dues billings and prospective member packets, at local educational institute campuses, etc. Be sure to market your conference through “related” or “like-minded” groups.

- Take a look at your conference through your attendees eyes. Can you answer “what’s in it for me?” Is there enough content to make it worth attending? Are your marketing materials accurately conveying the value of the meeting?

- Provide a significant discount for early enrollment—NSTA has a significant registration spike for our early bird registration rate.

- Have a big name/recognizable presenter—this has been an attendance trigger for NSTA.

- Offer a guarantee. If the attendee isn’t fully satisfied, refund their money.

These are some ideas to get our conversation started. Do you have a great idea you can share? What has worked for your group and most importantly, what has not worked? Post a comment below or e-mail me at aodonnell@nsta.org and share with your fellow leaders. Remember, the success of this blog is dependent on your participation!

Thanks to everyone who posted a comment and e-mailed me directly. Boosting meeting attendance seems to be on everyone’s mind. While there is usually no one “quick fix,” here are some ideas to think about:

NSTA Press free book chapters

By Claire Reinburg

Posted on 2010-03-12

![]() Did you know that nearly every NSTA Press book has a free sample chapter you can download from the Science Store? To make it easier for science teachers to locate these resources, we’ve created a new page listing the freebie chapters that include lessons and activities: visit www.nsta.org/publications/press/chapters.aspx to learn more. We’ll add to the list as new books come off press.

Did you know that nearly every NSTA Press book has a free sample chapter you can download from the Science Store? To make it easier for science teachers to locate these resources, we’ve created a new page listing the freebie chapters that include lessons and activities: visit www.nsta.org/publications/press/chapters.aspx to learn more. We’ll add to the list as new books come off press.

![]() Did you know that nearly every NSTA Press book has a free sample chapter you can download from the Science Store? To make it easier for science teachers to locate these resources, we’ve created a new page listing the freebie chapters that include lessons and activities: visit www.nsta.org/publications/press/chapters.a

Did you know that nearly every NSTA Press book has a free sample chapter you can download from the Science Store? To make it easier for science teachers to locate these resources, we’ve created a new page listing the freebie chapters that include lessons and activities: visit www.nsta.org/publications/press/chapters.a

Recording in a journal—video clips model using a science journal

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2010-03-12

Not having any “kids” at home these days, I have to make a special effort to learn about the programs my preschool students are watching on television. I like to know the opening songs so I can impress the children!

After spending some time on the Sid the Science Kid site I found these activities (with video clips demonstrating them) that are good basic suggestions of how to “do” science with young children.

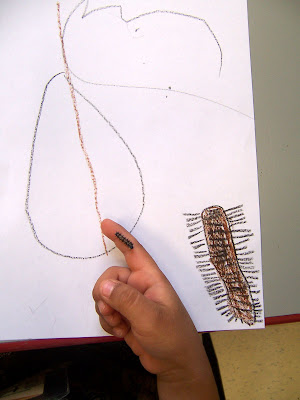

The narrator is a little perky for this adult—I think children are suspicious anytime people try too hard to get them interested—but I suppose the marketing people know what kids like. The videos portray small groups of 5-6 children. In some clips the children seem to be in first grade, and younger in others, judging from their handwriting. What is wonderful is how, for every activity, the children draw and write observations in their journals (spiral bound notebooks or drawing pads). Although the activities seem to be teacher structured, the children have very individual records in their journals. A nice feature is the variety of teacher voices, and teachers and children in the videos and the interesting activities. (I do question allowing the children to eat the fruit that they collectively dug out of a block of ice melting in a plastic tub. I would suggest freezing fruit that will be eaten into individual ice cubes, or freeze small toys or coins into a larger block for group exploration, not eating.)

A few resources about science notebooking:

Using Science Notebooks in Elementary Classrooms by Michael P. Klentschy (NSTA Press, 2008). “This book makes the case for using science notebooks strategically—promoting hands-on observing, recording, and reflecting—and demonstrates how best to do so…Connecting language arts to science through expository writing, the book presents proven techniques such as scaffolds, sentence starters, discussion starters, and other writing prompts to encourage students to build on current knowledge.”

Five Good Reasons to Use Science Notebooks by Joan Gilbert and Marleen Kotelman, an article in the November 2005 NSTA journal, Science and Children with a full discussion of how to use science notebooks.

November 2009 issue of the NAEYC journal, Young Children, explores science in the early years. See Science in the Air by Sherrie Bosse, Gera Jacobs, and Tara Lynn Anderson, for ideas on documenting science explorations and observations.

Science notebooking begins in early childhood wit h drawings. Your students might enjoy watching some others do science in the Sid the Science Kid clips. Perhaps they would even like to make their own video!

Your students might enjoy watching some others do science in the Sid the Science Kid clips. Perhaps they would even like to make their own video!

Peggy

Not having any “kids” at home these days, I have to make a special effort to learn about the programs my preschool students are watching on television. I like to know the opening songs so I can impress the children!

After spending some time on the Sid the Science Kid site I found these activities (with video clips demonstrating them) that are good basic suggestions of how to “do” science with young children.

Latest from NSTA's online outposts

By Howard Wahlberg

Posted on 2010-03-10

Recent Activity on NSTA’s various online outposts

On our listservs, there are great conversations about moldy cats (yes, that’s right, moldy cats) on our Biology list, engineering and Newton’s laws on our General Science list, class size on our Physics list, and whether or not poop is a living thing or not on our Elementary list.

In NSTA’s online professional learning communities, make sure to check out all the new presentation resources for our Philadelphia Conference.

On our “core site” (www.nsta.org): everyone’s gearing up for our National Conference on Science Education this March 17–21 in Philadelphia. Write your own declaration of independence and join your fellow educators this March in Philadelphia!

On Facebook, lots of folks have been discussing plans for the National Conference.

On LinkedIn, you can now find a jobs subgroup, that re-posts all of the listings on the NSTA Career Center.

And of course, on our Twitter stream, science educators are tweeting and re-tweeting about our upcoming national conference in Philadelphia!

Recent Activity on NSTA’s various online outposts

On our listservs, there are great conversations about moldy cats (yes, that’s right, moldy cats) on our Biology list, engineering and Newton’s laws on our General Science list, class size on our Physics list, and whether or not poop is a living thing or not on our Elementary list.

Exemplary science program monograph series

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2010-03-09

The seventh ESP monograph, now in final stages of editing, should be available for the three NSTA fall area conferences. This series from NSTA Press has focused on meeting the reforms central to the National Science Education Standards. Titles available are

The seventh ESP monograph, now in final stages of editing, should be available for the three NSTA fall area conferences. This series from NSTA Press has focused on meeting the reforms central to the National Science Education Standards. Titles available are

- Science for Grades PreK–4;

- Science for Grades 5–8;

- Science for Grades 9 –12;

- Professional Development of Science Teachers;

- Science in Informal Education Settings;

- Inquiry: The Key to Exemplary Science; and

- Science in a Social and Societal Contexts.

NSTA members are invited to use these monographs and to volunteer to help as members of the National Review Team for the future ESPs.

In addition, plans for ESP 8 are in the works. It is to focus on NSES Goal 4, which seeks to identify exemplary situations that illustrate preparation of students for science- and technology-related careers. Your nomination of potential authors (teachers) in your state would be of great help! In addition, you are invited to assist some of your outstanding teachers in preparing an outline, and it would be great if you were not only encouraging, but also if you would consider being a co-author.

Please direct questions, suggestions, or ready-to-be contributors to Bob Yager, who coordinates the national efforts. E-mail robert-yager@uiowa.edu; call (cell) 319-541-2857 or (office) 319-335-1189; or write to Room 769 VAN, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242.

Looking for a challenge

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2010-03-08

I’ve been teaching middle school science for 15 years, and I love my job. But I’m wondering what other opportunities there might be for sharing and expanding my experiences and knowledge. I don’t think I want to be an administrator, but I’m open to suggestions for a new challenge.

—Brita, Virginia Beach, VA

I’d be interested in seeing any formal research on the topic, but I’ve observed many teachers with 10 to 15 years of experience develop the same feelings. They have a good repertoire of teaching strategies, and they are comfortable with their content knowledge. Although they are very confident in their classroom role, they feel a need to explore additional ways to contribute to the teaching and learning processes.

I’d be interested in seeing any formal research on the topic, but I’ve observed many teachers with 10 to 15 years of experience develop the same feelings. They have a good repertoire of teaching strategies, and they are comfortable with their content knowledge. Although they are very confident in their classroom role, they feel a need to explore additional ways to contribute to the teaching and learning processes.

Moving beyond the comfort zone of the classroom requires risk-taking and a willingness to take on additional challenges. The term “teacher leadership” covers a variety of roles teachers can play in their schools. You might investigate opportunities to serve as a science advocate on school committees and task forces, a department chair, instructional coach, mentor, advisory board member, grantwriter, team leader, or project director.

You could become more active in NSTA or your state affiliate by volunteering for committees or running for a leadership office. Consider sharing your experience, expertise, and enthusiasm by writing articles for NSTA journals or NSTA Reports, or presenting at NSTA’s regional or national conferences. Connect with others through the NSTA email lists and the NSTA Communities. You’ll meet interesting people who share your passion for science and will invigorate your intellect.

Expand your knowledge in different content areas. Take a look at NSTA’s Science Objects, which are free, online modules on a variety of topics. (Being certified in chemistry, I did not have many opportunities to study the earth sciences in college, so I really enjoy these modules). Also consider enrolling in courses at museums or other informal agencies, either on-line or on-site. Experiment with new technologies, including social networking, podcasting, video sharing, wikis, Moodles, and blogs.

Join or start a book discussion group, focusing on science-related themes, using NSTA Recommends for ideas. Offer to do workshops for teachers in your district or others. A district I worked in used teacher leaders to do most of the summer academy sessions. You also could check with a regional service agency or informal science organization to see if they need workshop presenters or advisors. Teaching at the college level can be a great experience, too.

Sabbatical leaves are not as common as they used to be, but your school or district may still grant them for graduate work, travel related to your teaching assignment, or internships at university labs or museums. It may be time to upgrade your credentials through additional graduate study or by working on National Board Certification.

Another exciting opportunity is being a Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA). Schools or districts release experienced teachers from some or all of their classroom duties and assign them to assist with strategic planning, professional development, coaching, induction, curriculum design, or special projects. These positions, often funded through a grant, usually last only a semester or two. The cost to the district is the salary of a full-time substitute. I worked with a TOSA whose role was to mentor elementary teachers in science. She modeled inquiry-based strategies in classes, acquired materials for lab activities, and provided professional development. Since she was an active teacher, she had a positive rapport with the teachers in a non-threatening, non-judgmental way. Her salary was paid by a professional development grant.

Don’t overlook the option of earning administrative credentials. Your insights and experience would make you a valuable resource for the science faculty. Working with a principal or curriculum director who understands the unique demands of science instruction would be a dream come true for many science teachers. Even if you never become a principal or central office administrator, the coursework, reflective processes, and internship can provide close encounters with another component of the education system. Having administrative credentials can open the door for other opportunities, too.

You’ll never know when an opportunity for presenting, teaching, publishing, or advisory work will present itself. Have an up-to-date resume/vita including your educational background, your credentials or certificates, a description of your teaching responsibilities, a list of workshops or presentations you’ve conducted, your professional recognitions and awards, any publications, and extra-curricular and community service. Also get business cards and have a professional-looking photograph taken.

As a potential teacher leader or administrator, don’t underestimate the value of your contributions. I’m sure you have the skills and knowledge, as well as a passion for science, to become a valuable resource not only to your students but also to the profession. It will be a rejuvenating experience.

Photo source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/frankieroberto/3617081841/

I’ve been teaching middle school science for 15 years, and I love my job. But I’m wondering what other opportunities there might be for sharing and expanding my experiences and knowledge. I don’t think I want to be an administrator, but I’m open to suggestions for a new challenge.

—Brita, Virginia Beach, VA

Seasonal scavenger hunt

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2010-03-05

Early spring flowers on a red bud tree.

Red bud tree leaves in fall.

Give your students practice making observations by doing a seasonal scavenger hunt that will require closer looks at the familiar landscape to see what has changed. (Thanks to the University of British Columbia Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research for the idea.)

Does the tree (with branches low enough to see) have tightly furled flower or leaf buds, leaves the size of a squirrel’s ear, or leaves that are fully grown and changing color? Checklists can use both words and pictures to list items.

Use a new checklist for each season and include some of the following items to look for if they apply to your school yard:

Plants

- Leaf size on deciduous plants (choose any or a particular plant)

- Flower buds forming, blooming, forming seeds(choose any or a particular plant)

- Flower bulb leaves growing above ground, dying back

Animals

- Baby animals in the fields

- Tracks in mud, sand, or snow

Birds

- In groups or alone

- What are they eating?

- Birds building nests

Insects and other small animals

- Bees or other pollinators on flowers

- Small animals (roly-polies, caterpillars) visible in the garden

Weather

- Temperature

- Precipitation

- Windy or calm

- Snow on the ground

- Ice on water bodies

- People dressed in boots, coats, sandals, shorts, carrying umbrellas.

"Honesty" plant in bloom in spring.

"Honesty" plant seed pods in fall.

The scavenger hunt observations can be posted each month to make it easier to see how the observations have changed over the year. Some months no student will see a bee and other months every student will see some.

What other items should be added to an outdoor scavenger hunt list for your schoolyard?

Peggy

Early spring flowers on a red bud tree.

New blog on the block

By Howard Wahlberg

Posted on 2010-03-05

Welcome to the Chapter and Associated Groups (CAG) Blog! Let me start by introducing myself. I’m Anne O’Donnell, CAE. I have been in association management for almost 20 years serving a wide variety of associations and professions. I am pleased to be here at NSTA and hopefully will be able to meet many of you in Philly at the Annual Conference.

The Chapters and Associated Groups blog is dedicated to helping the past, current and future leadership of NSTA’s CAGs. Highlighting helpful resources, providing leadership tips and association management solutions, this blog is designed to help keep our CAGs strong!

Your participation is critical to the success of this blog! I encourage you to submit ideas, post, and guest blog! As always, if you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please let me know—I’m just an e-mail away: aodonnell@nsta.org.

See you in Philly!

Welcome to the Chapter and Associated Groups (CAG) Blog! Let me start by introducing myself. I’m Anne O’Donnell, CAE. I have been in association management for almost 20 years serving a wide variety of associations and professions. I am pleased to be here at NSTA and hopefully will be able to meet many of you in Philly at the Annual Conference.

Science Education Leadership

By Claire Reinburg

Posted on 2010-03-05

Leaders from diverse constituencies in science education bring their insights and advice together in an important new book from NSTA Press. Science Education Leadership: Best Practices for the New Century discusses how leaders at the local and national levels, from science teachers to district supervisors to university faculty, can forge new paths in the years ahead toward the goal of science literacy for all. In the Preface, editor Jack Rhoton credits chapter authors for detailing for leaders at all levels “how to contribute to the success of science education and how to develop a culture that allows and encourages science education leaders to continually improve science programs.” We’ve posted Rodger Bybee’s excellent chapter in which he summarizes five 21st century workforce skills that science education can focus on to better prepare students for jobs and professional fields in the global economy. Visit the Science Store to learn more about Science Education Leadership, and scroll down below the book description to download the chapter “A New Challenge for Science Education Leaders: Developing 21st Century Workforce Skills.”

Leaders from diverse constituencies in science education bring their insights and advice together in an important new book from NSTA Press. Science Education Leadership: Best Practices for the New Century discusses how leaders at the local and national levels, from science teachers to district supervisors to university faculty, can forge new paths in the years ahead toward the goal of science literacy for all. In the Preface, editor Jack Rhoton credits chapter authors for detailing for leaders at all levels “how to contribute to the success of science education and how to develop a culture that allows and encourages science education leaders to continually improve science programs.” We’ve posted Rodger Bybee’s excellent chapter in which he summarizes five 21st century workforce skills that science education can focus on to better prepare students for jobs and professional fields in the global economy. Visit the Science Store to learn more about Science Education Leadership, and scroll down below the book description to download the chapter “A New Challenge for Science Education Leaders: Developing 21st Century Workforce Skills.”