Engineering Encounters

Argumentation to Inform an Engineering Design Decision

An engineering argument in a second-grade classroom

Science and Children—July/August 2022 (Volume 59, Issue 6)

By Tejaswini Dalvi and Jihan Mehidee

For elementary students, engagement in engineering provides multiple learning opportunities through hands-on experiences, learning from failures, and engagement in critical thinking (Hill-Cunningham, Mott, and Hunt 2018). Participation in an engineering design process (EDP) provides students with decision-making opportunities to inform their design solution, thereby strengthening students’ reasoning skills. This article describes an activity, as conducted in a grade 2 classroom, that prepares and engages students in argumentation using evidence, which is not often addressed in early elementary grades. In the described activity, comprising a portion of the EDP, students participate in one specific aspect of the design process: conducting extensive research to select and argue for a material from the given set, for a specific purpose. The activity attempts to attend to the performance expectation (PE): K-2-ETS1-3 and the Performance Expectations 2-PS1-1 and 2, with an emphasis on the practice of argumentation from evidence.

Approach to Engineering

Researching materials to inform design decisions is an important part of the design process. This activity relates to the importance of studying materials to make a justified decision and supports students’ ability to fulfill the task through reasoning and evidence-backed justification. To gather evidence, students participate in material testing activities and reading informational text, which helps them select an appropriate material. The goal is to engage students in planning and conducting an investigation to collect data, analyze informational text, and further, use the data from the two sources as evidence to argue for the best material per its properties for making a rain jacket.

The activity was completed in two 35-minute sessions and was part of a longer science-engineering unit. The task introduction and the investigations were done on day 1, and the text reading and analysis, final argument, and wrap-up were done on day 2. Teachers may choose to do this as a stand-alone activity that is spread across shorter multiple sessions or as a single longer session. If students are not experienced in decision-making discussions, teachers may focus on doing one part per session over a period of multiple days.

Introducing the Task

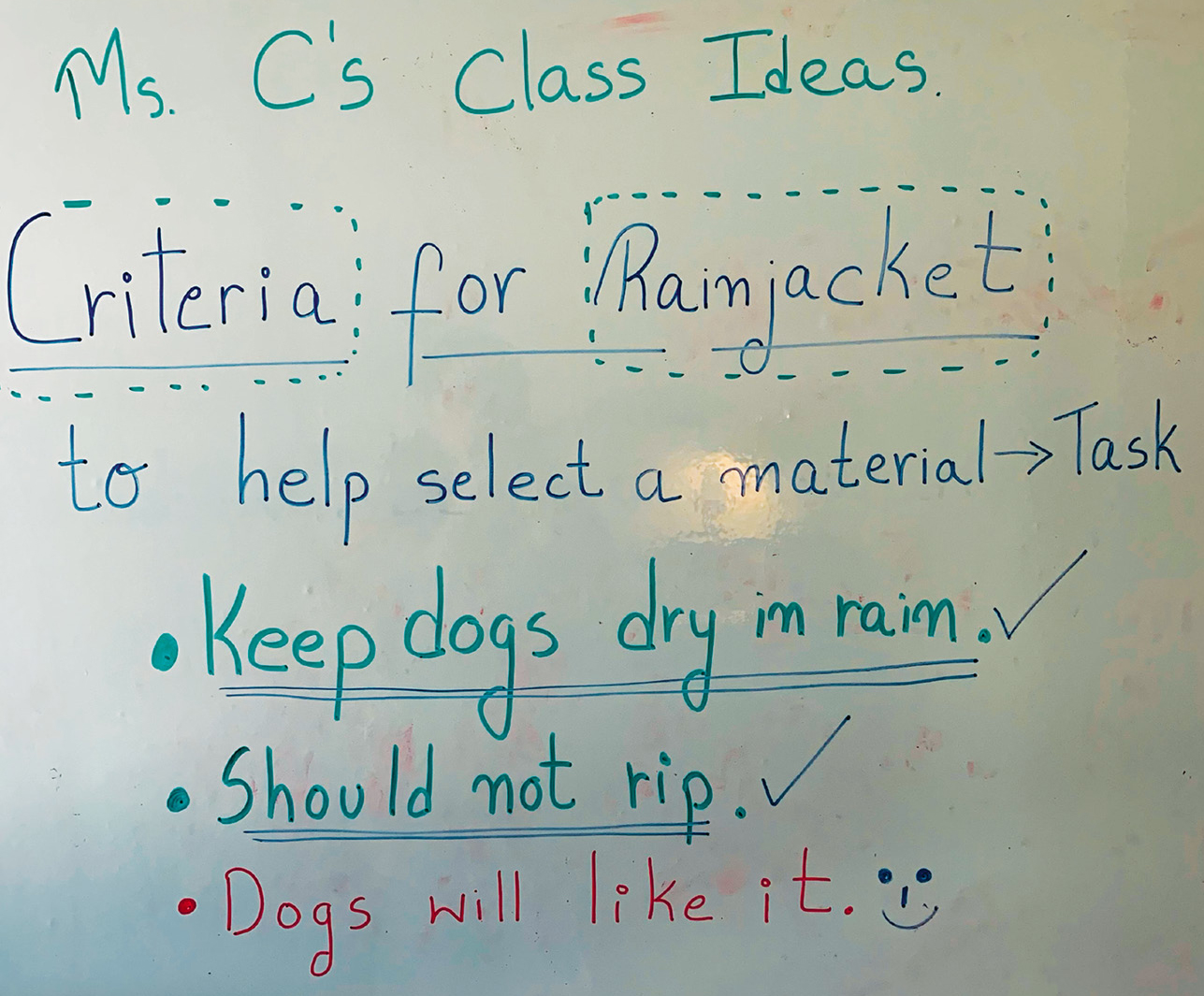

Using the empathy lens of designing to help others (Hynes and Swenson 2013), the teacher introduced this activity by sharing a problem that she needed help with. The teacher shared that she needed to design a rain jacket for her dogs. To do so, she needs to pick one of the following materials: felt fabric, plastic bags, or aluminum foil. The teacher shared that these materials were selected because they were easily available and used for sewing purposes and displayed 12 × 12 sheets of the materials. The teacher then asked, “How do we decide on the most suited material for making rain jackets?” Some students wanted to use all the options, while others made quick choices without reason. The teacher first clarified that only one material could be used. Next, for students who made a quick choice, she asked, “Why do you choose your material?” She wanted her class to think about the specific nature of the problem and then make a choice. The opening facilitation was structured to help students identify the need to understand the problem fully before suggesting ideas. Students responded, “I like foil because it’s shiny” and “rain jackets look like plastic.” Some students were starting to reason while others stated personal preference. The teacher took this opportunity to steer her class away from personal preferences and instead think about how to make a choice. Together, the class listed two requirements or criteria for the rain jacket material: material should be able to keep the dogs dry and not rip easily (Figure 1).

Material criteria.

Investigate Material Behavior

Based on the decided requirements, the teacher asked, “To keep the dogs dry, what material will help?” Students suggested, “My rain jacket is like plastic,” “Maybe foil,” and so on. The teacher next asked, “Is there something we could do to check which choices will work?” The intent was to lead students to plan and investigate if a certain material would work or not. The teacher added that to investigate which choices will work, the class would use a toy dog instead of a real one. A small plush toy dog was provided for this purpose. Students suggested wrapping a toy dog with the materials and then placing it in rain to check. Some suggested testing under a shower or using a hose. To test the materials, the class decided that a toy dog should be wrapped with a piece of each material, and then tested with water. Instead of giving students a plan, the teacher involved them in the planning process. The intent was to help students understand the need to check which material is waterproof, a property of the rain jacket that will help the class select a material.

Next, students engaged in conducting investigations to test which materials exhibit the required properties. The teacher discussed the test conditions and test criteria to talk about fair testing. For investigations, equal size pieces of each material were used. The teacher shared that “by using the same amount of each material to wrap the toy dog, we are being fair in our tests.”

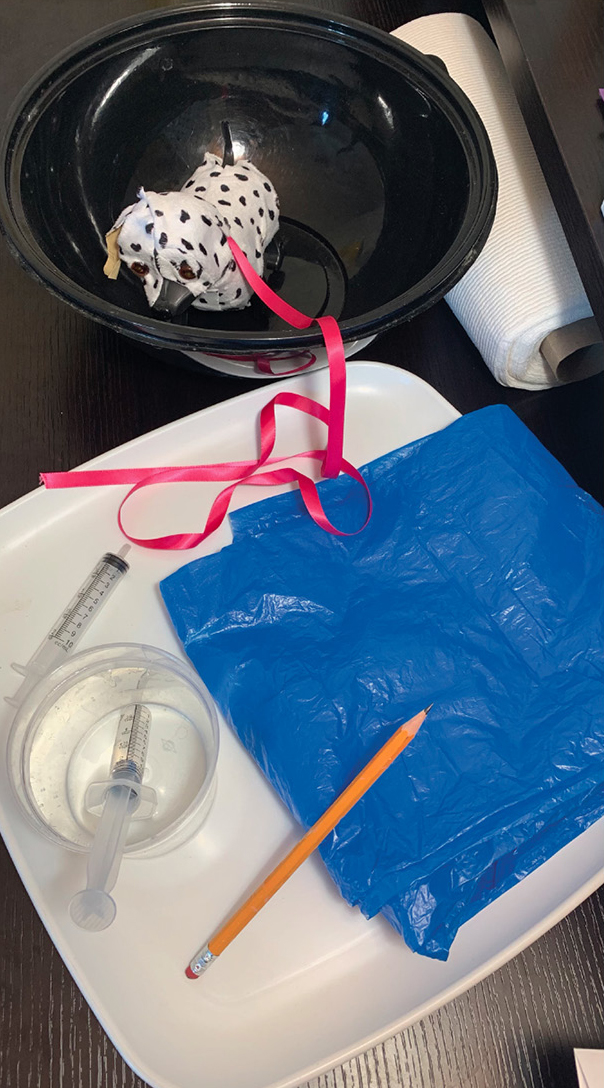

The teacher orchestrated this task, with all groups testing one material at a time and documenting results in a table. The class worked in groups of three students. Students wrapped the toy dog with one material at a time, placed it in a big bowl, used two full syringes to pour water over the toy, and then waited for a minute before checking the toy dog . Caution around wet, slippery surfaces was discussed as an important part of safety during investigations.

After testing (Figures 2 and 3), each group was asked to look at the results, suggest a suitable material, and explain why they picked it. A group choose plastic because “After the plastic was taken off, we saw the dog was wet nowhere.” The teacher highlighted how investigations provide information that helps make a choice.

Testing setup.

Testing the raincoat.

Analyze Texts to Learn about Materials

On day 2, the class read an article on use of rain jackets and their materials. The article was put together by the elementary ELA teacher based on the class’s reading level. The one-page article included two paragraphs in big font and pictures. It described the use of rain jackets and materials they are usually made of and why. First, the teacher read the article out loud, and later the students, in their small groups re-read the article. As the teacher read, the students were guided to underline important information about the different materials. During the small-group task, students were asked to highlight parts where they found helpful information about rain jacket material. Individual students were given a different color pencil, so that even as they worked in a group, each student could preserve and see the value of their individual contribution. Teachers may want to use similar strategies to promote student participation and engagement when working in small groups.

As the class discussed the information about rain jacket materials and their properties, students pointed to the word waterproof, a property they studied during their investigations. The reading proved to be another source of evidence. The reading and analyzing aspect of this activity supports building practice of argumentation where evidence plays a crucial role.

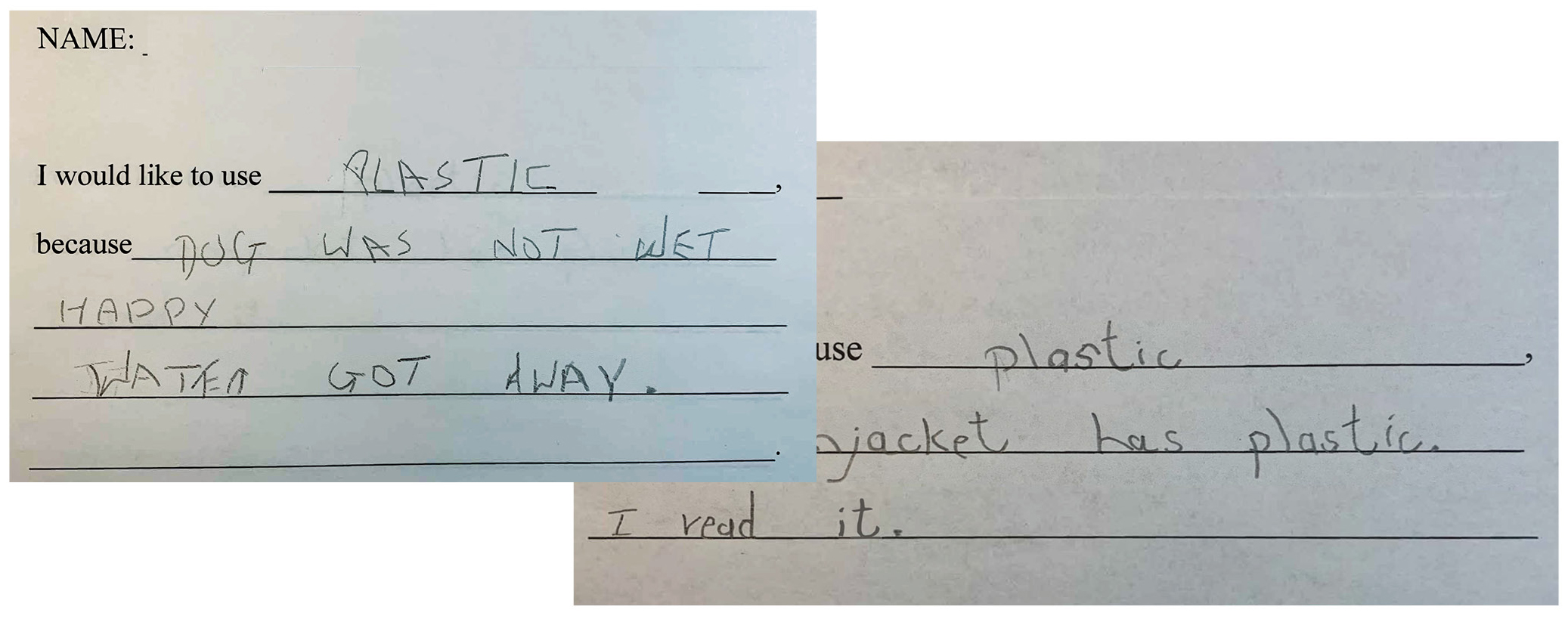

Preparing for the Argument

Preparing students to make an evidence-based choice was the most crucial part of the facilitation. First the students were asked to individually make a choice. The teacher provided each student with ‘My Material Choice Card’ with a pre-written prompt, “I would like to use _______, because ____________” (Figure 4). A different color note was used for each material choice. The teacher asked a few students to read their notes out loud. When reasoning was missing, the teacher asked, “How do you know that ___ (their choice) would be good to make rain jackets?” She reminded students of the material criteria and prompted them to revise their writing. Further she asked, “Were you thinking about the test or what you read, when you selected the material?” The intent was to help students connect their reasoning to their evidence from test observations and texts. For grade 2 students, it was important to see the value of initial testing, the reading tasks and how each provided for evidence. The teacher further discussed how engineers study materials for what they can do and where they can and cannot work. This information helps them decide which design, idea, or object to choose. We cannot always make choices based on personal preference; however, engineers think about how successful their choices are in satisfying a given task.

Sample student work.

The Final Argument

After each student made a choice, new groups were formed. Students selecting the same material were placed in one group. This class had two groups: foil and plastic sheets, which then argued for their material choice. Each student shared how their choice of material solved the problem. The teacher insisted on presenting reasons with evidence for their choice. Students used evidence from their investigations that the materials, kept the dog dry. When a student was unable to present evidence, the teacher made a suggestion like, “So your test with foil kept the dog dry? So you want the foil?” It was agreed that both materials can keep the dog dry.

At this point, the teacher reminded the class of the other criteria on their list: The material should not rip easily while wearing. The group that selected foil said they observed the foil developed small cuts, “It ripped when we took it off, we can’t use it again.” A few students agreed to the foil getting crumpled after use. The teacher asked them to evaluate their choices against both the requirements. The foil group changed to plastic. They suggested using strong plastic that did not rip. Their thinking reflects attention to the test criteria, while looking if the materials will serve the purpose (DCI: K-2ETS1-2). The class finally decided to use thick plastics for making doggie rain jackets.

Finally, with the class gathered on the rug, the teacher asked, “Do you all think we made a good choice of material?” While most students said “yes,” a few disagreed. A few students said they were unhappy because the material selected was not their first choice. The teacher first acknowledged the students’ feelings, and then suggested, “Let’s once again think about the problem and all the steps we took to solve it.” Using guided discussion format and the charts made, the class revisited the problem, criteria, and the process of how they selected the material. The teacher helped the class to review the various processes they were engaged in and recognize how those helped them decide a material, ultimately helping the dog. She highlighted how they worked as engineers by conducting research to select a material to help solve the problem, rather than simply using personal preferences. Wrap-up discussions like these help students make sense of their actions and see how the practices they were engaged in were helpful in solving a problem.

The article reports on the classroom activity as it happened. And thereby we acknowledge that there might have been certain missed opportunities in attending and responding to student ideas. Teachers may choose to provide individual students feedback on their materials cards, plan time for students to revise their writing, or include a structured feedback session.

Assessment and Teacher Facilitation

The activity proposes use of formative assessments to study students’ development of ideas. For assessment purposes, the material choice card and the investigation handouts were studied to understand how students present their reasoning. Using a completed material choice card (Figure 4), the teacher studied if individual students made a choice, gave a reason for their choice, and cited evidence for their reason. The teacher found that most students made a choice and gave a reason. However, the reason was not always linked to appropriate evidence. Students needed support in making connections between how the texts and the experiments provide them with information that helped them make a choice. The investigation handout helped study what observations students make and if they use those observations to reason their argument. As students worked in groups, or during discussions, the teacher posed questions to probe student ideas and thinking.

The facilitation played an important role in guiding students through testing, reasoning through choices, and building argument. Questions, as shared throughout, were used to guide students through discussions to reason their choices, as well as probe student ideas, uncover misconceptions, and help build arguments using evidence.

Conclusion

The activity illustrates early elementary students’ successful engagement in evidence-based reasoning. The hope is to encourage teachers to leverage appropriate facilitation scaffolds as questions and talk moves, to make argumentation accessible to elementary students. The activity highlights ways to engage students in not just testing but also the process of planning and setting up tests, and in further thinking about how and why the tests are aligned with the demands of the task. Along with engagement in practices, learning about the practices and how those relate to work of engineers allows students to see value in what they do, and makes engineering learning relatable and meaningful. ●

Supplemental Resources

Download activity resources at https://bit.ly/3Nvtyl3

Tejaswini Dalvi (tejaswini.dalvi@umb.edu) is an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston (UMB). Jihan Mehideen is an elementary teacher at Boston public schools in Brighton, Massachusetts.

Engineering Teaching Strategies Elementary