methods & strategies

It Takes a Village

Fostering community partnerships to create a citizen science project for elementary students

Science and Children—May/June 2023 (Volume 60, Issue 5)

By Richard Schaen, Janet Zydney, and Lauren Angelone

A key element of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) is for students to engage in authentic science and engineering practices that scientists and engineers perform in their jobs (NGSS Lead States 2013). One strategy to implement these standards within the school curriculum is for students to participate in citizen science projects. Citizen science provides an opportunity for anyone to gather data alongside scientists in authentic scientific discovery (California Academy of Sciences), which not only fosters the use of science and engineering practices (SEPs) but also scientific literacy. To successfully implement citizen science projects in the classroom, Hayes, Smith, and Midden (2020) recommend that teachers align the projects with the standards, find accessible sites to collect data, and develop partnerships with professional scientists, community members, and other key stakeholders. The problem is that sometimes partnerships can interfere with students’ inquiry if not implemented well (Zydney, Angelone, and Rumpke 2021). In this article, we share how to cultivate partnerships that will help meet your learning objectives (Hod, Sagy, and Kali 2018).

Background

Our partnership began with Richard Schaen, a first-grade teacher in the Wyoming City School District in Wyoming, Ohio, and Janet Zydney, an education professor at the University of Cincinnati who was also a parent of a former student. At the start of the school year, Janet reached out to Richard to see if the school would be interested in participating in a study about the use of technology to foster science practices through citizen science. This project seemed to dovetail well with Richard’s goal to create a school garden, so we started to work together on doing a citizen science project within a school garden.

Over the course of a couple years, we cultivated several relationships, including with the local government, the school administration, another university, and two non-profit organizations. This article explains how these partnerships were developed over time to enact the strategy of using citizen science projects to bring authentic science experiences into the classroom by creating a school garden.

Obtaining Funding

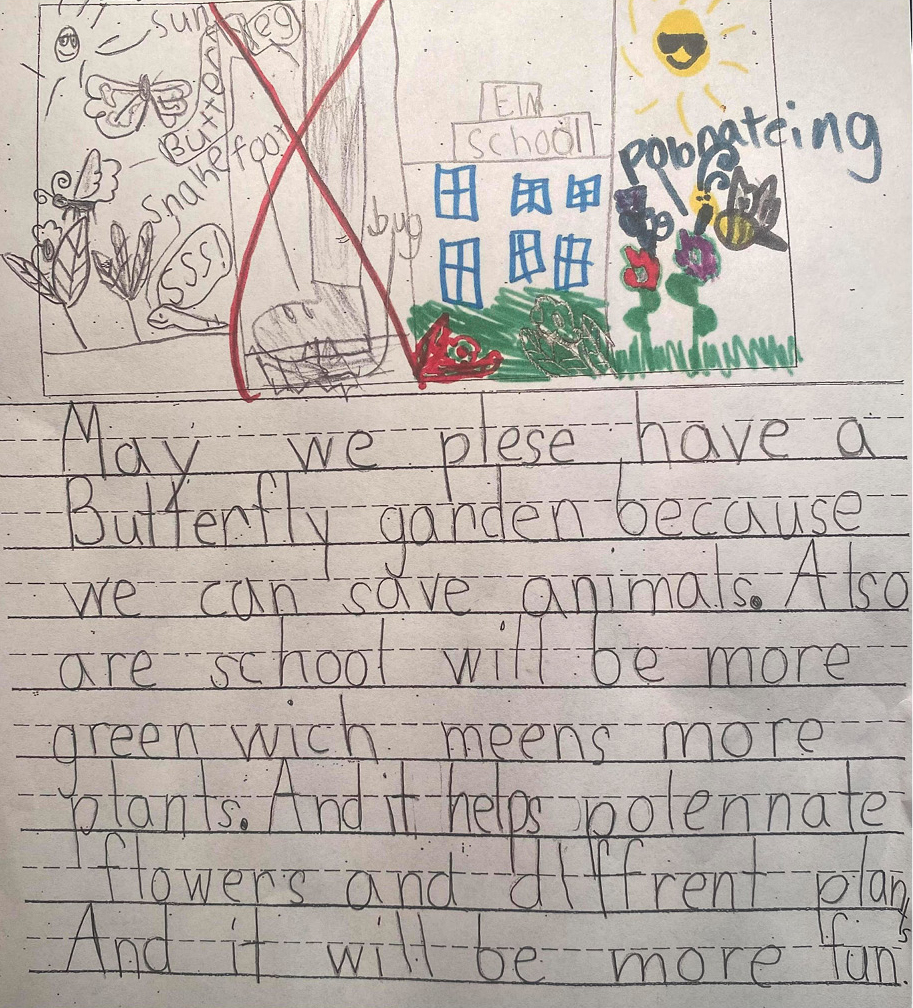

The first partnership was initiated with the local government when the city opened an environmental grant request for proposals. We needed money to be able to create the school garden, so we jumped at the opportunity. In preparing this grant application, we asked students to write letters explaining why they felt our school deserved a garden (Figure 1). This was a great chance for the students to use their persuasive writing skills in an authentic way (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.1.1). For schools looking for a list of grants to start their own gardens, is a good place to start.

Student letter.

Connecting with Organizations

As part of our grant application, we needed to create a budget with all the plants and materials that would be needed for the garden. The grant provided up to $500, so we knew we needed to keep costs to a minimum. We started to research where we could obtain wholesale plants and came across a program at The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden to increase the number of pollinator gardens planted in the region. We didn’t have any personal connections at the zoo, so we emailed the generic information account and received a reply from the organizer wanting to meet with us. In February 2020, we met with the zoo’s horticultural department, and they agreed to donate plants. They also agreed to give guidance about garden planning—a big part of their outreach program was connecting with students. When we applied for the grant, our partnership with the zoo gave the application additional credibility and greater purpose that extended our garden beyond the needs of our school.

Considering that many zoos and greenhouses have their own outreach programs, forming connections with these organizations is an obvious choice for teachers who are interested in creating similar projects at their schools.

Involving School Administration

We didn’t get the grant. It was a disappointment, but the writing lessons that students learned through the grant application process were what was most important, not to mention the life-lesson about creating new opportunities from failures. As it turned out—after an extended time during the COVID-19 pandemic while our garden plans remained on hold—the letters the students had written and our partnership with the zoo ended up being very valuable. They helped persuade our school district to provide money for the topsoil and mulch we still needed for the garden. Another factor that worked in our favor was that there was an underutilized grassy area between a walkway/ramp that provided access to the playground. The district agreed that this would be a great area to be beautified by a garden.

Connecting with Community

Our next challenge was finding resources to help build the garden. In April 2021, we sent out a message to parents and other community members and soon had an ample supply of garden volunteers. On the day we created the garden in May 2021, teachers, family members, and community members all worked together. Our superintendent even surprised us with a visit to check things out.

Students from different grade levels also contributed, doing chores like picking weeds and shoveling soil. While the garden was led as a collaboration between the school’s first-grade classes, it was understood that the garden would be available on an ongoing basis for projects for any class. When it was completed, the school’s “Inspiration Garden” had 40 different types of plants, with a total of over 100 plants in all. The zoo helped us pick plants from its greenhouses that attracted a wide variety of pollinators. These plants included butterfly bushes, cone flowers, bee balm, asters, salvia, daisies, lavender, and milkweed. Because the zoo donated the plants, our only costs were $279 for topsoil and $75 for mulch. The garden was certified by the zoo as an official pollinator garden and was a source of pride for the whole school.

Another University Joins In

As mentioned earlier, while the school’s goal was to create a garden, the university wanted to do a study on how technology can be used to enhance citizen science projects. We planned to use Project Noah (www.projectnoah.org) for the students to share their research and observations about plants and pollinators in the garden. Project Noah is a free citizen science platform that supports discussion among users and scientists. We had the technology expertise, but we needed someone with expertise in science education. So, we pulled in Lauren Angelone, a science education professor from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. We all then worked together to create lesson plans. Later we recruited the school’s other first-grade teacher to help create videos for these lessons so that remote learners could benefit from them, too.

The lessons covered all stages of gardening, from planting seeds to collecting data. Before the garden was established, the students learned about pollination and planted zinnia seeds in the classroom in compostable pots made from newspapers. The steps to make these compostable pots can be found online (see Online Resources). Any wildflower seeds would have worked. We chose zinnias because they were larger seeds and easier for the students to work with. When the seeds began to grow, the students eagerly checked the pots each morning when they first entered the classroom. Though pollination is a second-grade standard in the NGSS, we felt it was necessary to introduce the concept to support the larger question that would be the focus of the broader investigation, “Which plants are best to include in a pollinator garden?” This question allowed us to support understandings in the NGSS standard 1-LS1-1 around the structures of plants as well as crosscutting concepts of structure and function.

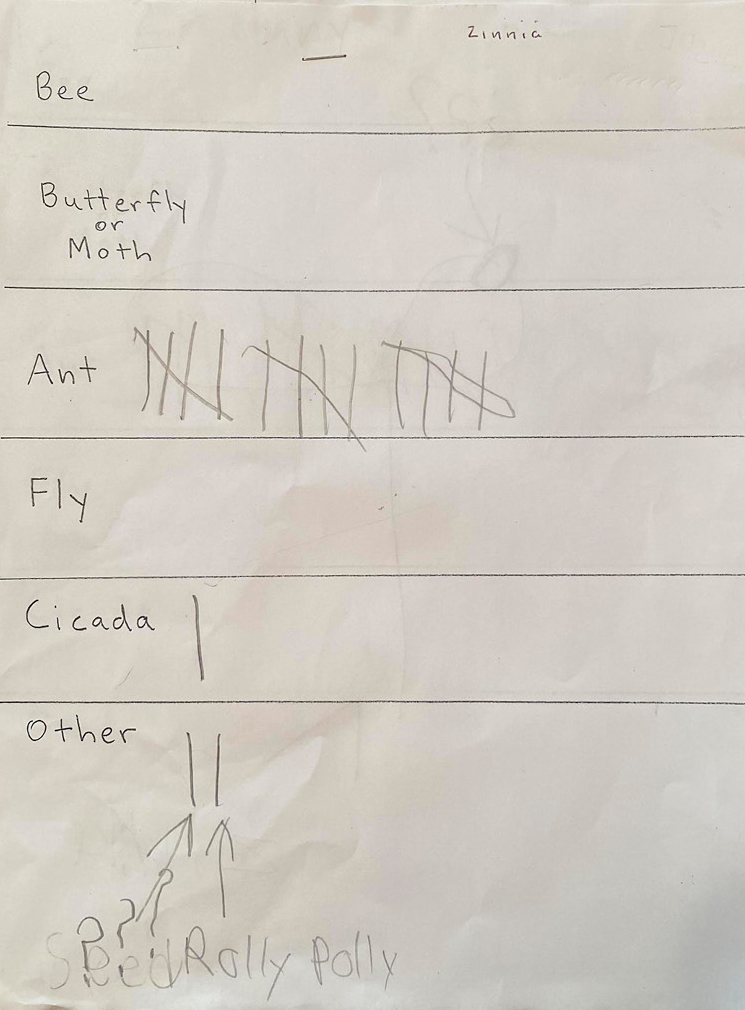

Later, in connection with lessons on garden design, the students transferred their pots into a corner of the garden that had been reserved for the zinnias. This led to an activity where the students used iPads to photograph the zinnias and the insects that visited them. The students also recorded their observations of insects that visited the zinnias. Through formative assessments on data collection, we knew that keeping organized data was an area where the students needed improvement (CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.1.MD.C.4). We created data sheets where the students used tally marks grouped in bundles of fives to keep track of how many different types of insects visited the zinnias (Figure 2). These lessons did not always go as planned. In one scene to which many teachers can relate, many of the students unexpectedly left their observation posts to chase a lizard that they discovered on the other side of the garden.

Data sheet of insect observations.

Ultimately, the goal of these activities was for the students to decide if zinnias were good plants for attracting pollinators. We used the students’ completed data sheets and conferenced with them for summative assessments to interpret their data to give reasons why zinnias were good plants or not for pollinator gardens. The data sheets supported the science practice of constructing evidence-based explanations.

We also included safety lessons throughout the project. For example, we taught rules about insects in the garden, such as about staying away from ones that might sting. We focused on how to safely handle the iPads, such as by always holding them with two hands. In addition, we stressed the importance of sun protection and staying hydrated, and we allowed the students to go to shaded areas if they needed breaks. We also reminded them of the importance of hand washing when they returned inside after being in the garden.

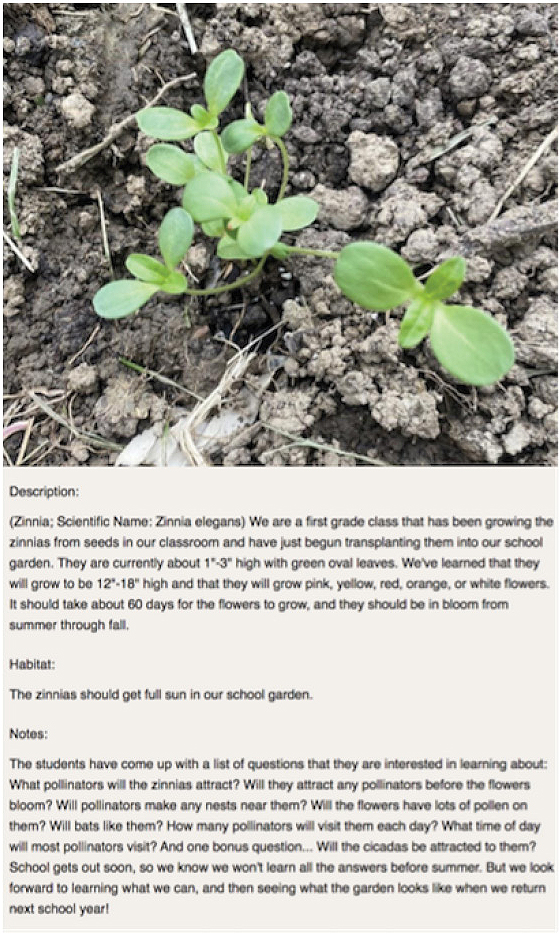

We then used a mission we had created on Project Noah titled Pollinator Detectives where participants could share about good plants for attracting pollinators (see Online Resources) and then engage in argumentation with peers and scientists. This screenshot shows information we shared (Figure 3). Other classes have since added their own observations. For teachers who are interested in using this mission with their own students, the lesson plans and instructional videos we developed can be found at http://cech.uc.edu/pollinatordetectives.

Pollinator Detectives screenshot.

Given that universities are often looking for schools to test out dynamic teaching methods, forming connections with them is a great resource for teachers to implement larger projects.

Collaborating with Pollination Experts

One of the challenges with citizen science sites like Project Noah is that teachers often do not know the scientists with whom they are collaborating. We wanted to make sure the students were interacting with scientists that were interested in their data and that would help further develop science and engineering practices. We did some research to look for local experts on pollination and located a non-profit focused on the importance of protecting pollinators, Queen City Pollinator Project (QCPP). Its naturalists agreed to monitor our postings on Project Noah and to respond with comments of their own.

Although we knew the QCPP naturalists that would be responding to our students, the comment feature of Project Noah is open to others. We used this as an opportunity to incorporate lessons on internet safety—lessons about the dangers of sharing personal information and about the importance of children’s internet usage being monitored by adults. We also used the comment feature to communicate with the school’s other first-grade class about an observation they made, which tied in with a lesson about the role of citizen scientists.

The naturalists engaged us in argument from evidence and challenged us to learn new things by raising questions. One example was when they asked us why it could be a good idea to plant parsley near the zinnias. Through research we did as a class, we learned that parsley is a food source for swallowtail caterpillars and that the zinnias are food for when they turn into butterflies. It was a nice link to the garden design aspect of our project.

Our collaboration with the QCPP naturalists provided a good capstone for the project. Each day until the project ended, the students always asked when we would check Project Noah to see if we received any new comments.

Reflection

In looking back at our two-year endeavor, the phrase “it takes a village” comes to mind. Each time we came to a small roadblock, we reached out to new community partners to help. Sometimes these were people we already knew, such as parents in the community. Other times they were local organizations that we found on the internet doing similar work to us. We were pleasantly surprised to discover how many organizations out there that are willing to help. It is often just a question of asking.

The project itself could be easily replicated in other classrooms. The only thing teachers really need to get started is a packet of seeds and some space to grow them. Teachers can then take the project as far as they want. It could be a chance for a school to start a garden. Especially after all the time we have spent on screens through the pandemic, it is a great opportunity to get outside. It is also a chance for a school to really build on its community connections.

Through cultivating partnerships, we ended up creating an authentic citizen science experience that brought excitement and a deep connection to the standards within our classroom. At the end of the school year, the students created memory books to share what they had loved about first grade. On the cover of one student’s book was a picture of him planting the zinnias in the garden (Figure 4). We look forward to our inspiration garden inspiring new memories and fostering scientific literacy for many years to come!

Student book cover.

Acknowledgment

This project would not have been possible without the incredible support from Stephen Foltz at The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden; Sylvana Ross, Carrie Driehaus, and Dr. Jenny O’Donnell from Queen City Pollinator Project; and Jen Dobson from Wyoming City Schools.

Online Resources

California Academy of Sciences Citizen science tool kit www.calacademy.org/educators/citizen-science-toolkit

Kids Gardening https://kidsgardening.org/grant-opportunities

Lesson Plans and Resources for the Pollinator Detectives Mission http://cech.uc.edu/pollinatordetectives

Newspaper Flowerpots www.nytimes.com/2021/03/06/at-home/grow-seedlings-with-newspaper.html

Pollinator Detectives Mission www.projectnoah.org/missions/2400396002

Project Noah www.projectnoah.org

Queen City Pollinator Project www.queencitypollinatorproject.org

Richard Schaen (schaenr@wyomingcityschools.org) is a first-grade teacher in the Wyoming City School District in Wyoming, Ohio. Janet Zydney (janet.zydney@uc.edu) is a professor in instructional design and technology at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio. Lauren Angelone (angelonel@xavier.edu) is an associate professor of instructional technology and science education at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Biology Citizen Science Earth & Space Science Life Science Elementary