Idea Bank

Digesting Solubility Rules

A method for memorizing solubility rules for ionic compounds

The Science Teacher—March/April 2023 (Volume 90, Issue 4)

By Jonathan McClintock

Solubility rules for ionic compounds are notoriously difficult to master. Because chemistry textbooks often present them as discrete facts, they are difficult to memorize and the relationships that exist between them can be obscure. This is unfortunate because a working knowledge of the solubility rules for ionic compounds is necessary for many activities in chemistry, including

- predicting the outcome of a precipitation reaction,

- deciding whether a substance is an electrolyte,

- writing ionic and net ionic equations for a reaction.

In this article, I will present a visual method for memorizing the solubility rules for ionic compounds using the periodic table, along with a mnemonic device based on the meals one eats throughout the day. I hope that general chemistry students of all ages will find themselves better able to “digest” the solubility rules for ionic compounds.

Setting up the periodic table

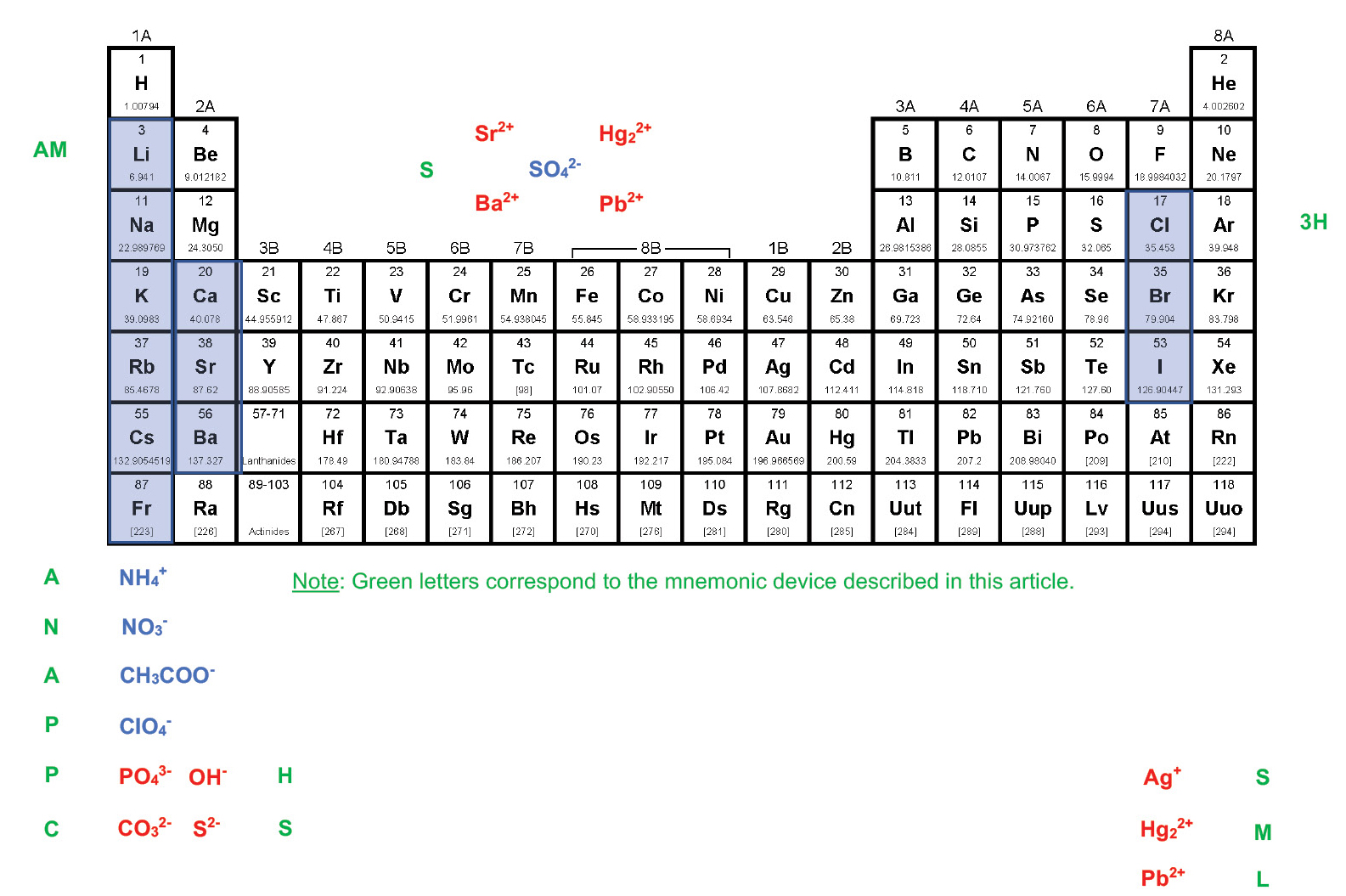

To employ the method described here, students must be able to highlight and label a periodic table as depicted in Figure 1. The following mnemonic device based on a “breakfast,” “lunch,” and “dinner” motif can help students label the periodic table appropriately:

Breakfast: AM. Almost No Appetite. Percolate Plain Coffee.

The first group of the periodic table is highlighted and labeled from the top down based on a breakfast theme. “AM” stands for the alkali metal cations, which should be highlighted in blue. “Almost” stands for the ammonium cation (NH4+), “No” stands for the nitrate ion (NO3–), and “Appetite” stands for the acetate ion (CH3COO–). Each of these ions should be written in blue. “Percolate” stands for the perchlorate ion (ClO4–), which should also be written in blue, whereas “Plain” stands for the phosphate ion (PO43–) and “Coffee” stands for the carbonate ion (CO32–), both of which should be written in red.

Lunch: Ham Sandwich on Carefully Sliced Bread

The second group of the periodic table is labeled and highlighted from the bottom up, based on a lunch theme. “Ham” stands for the hydroxide ion (OH–), and “Sandwich” stands for the sulfide ion (S2–), both of which should be written in red. “Carefully Sliced Bread” stands for the calcium, strontium, and barium cations, which should be highlighted in blue.

Snack: Snack Time

“Snack Time” stands for the sulfate ion (SO42–), which is written in blue above the transition metal elements and is surrounded by four cations written in red: strontium (Sr2+), barium (Ba2+), mercury (II) (Hg22+), and lead (II) (Pb2+).

Dinner: Three Hotdogs – Small, Medium, and Large

The next to last group of the periodic table is highlighted and labeled from the top down based on a dinner theme. “Three Hotdogs” stands for the three halide ions chloride (Cl–), bromide (Br–), and iodide (I–), which should be highlighted in blue. “Small, Medium, and Large” stands for the silver (Ag+), mercury (II) (Hg22+), and lead (II) (Pb2+) cations, which should be written in red.

Interpreting the scheme

Once the periodic table has been labeled, it is interpreted in the following way: Blue-colored ions tend to make an ionic compound soluble in water, while red-colored ions tend to make an ionic compound insoluble in water. Compounds that contain an ion not mentioned in the scheme are most likely insoluble in water if they are not coupled with a blue-colored ion.

Breakfast: AM. Almost No Appetite. Percolate Plain Coffee

The ions that have the greatest effect on the solubility of an ionic compound are listed here. If a compound has one of the blue-colored ions (Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, Fr+, NH4+, CH3COO–, or ClO4–), it will almost always be soluble in water. If a compound has one of the red-colored ions (PO43–, CO32–) it will almost always be insoluble in water unless those ions are combined with one of the cations that come before them (higher or to the left) in the scheme (Li+, Na+, K+, etc.). For example, although sodium phosphate (Na3PO4) is water soluble, calcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2) is not.

Lunch: Ham Sandwich on Carefully Sliced Bread

These ions have a less powerful effect on the solubility of an ionic compound. If a compound has one of the blue-colored ions (Ca2+, Sr2+, or Ba2+), it will most likely be soluble in water unless those ions are combined with one of the red-colored anions that come before them (higher or to the left) in the scheme (PO43– or CO32). For example, barium nitrate (Ba(NO3)2) is water soluble, while barium carbonate (BaCO3) is not.

If a compound has one of the red-colored ions (OH– or S2–), it will most likely be insoluble in water unless those ions are combined with one of the blue-colored cations that come before them (higher or to the left) in the scheme (Li+, Na+, K+, etc.). For example, calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) is water soluble, but iron (III) hydroxide (Fe(OH)3) is not.

Snack: Snack Time

The sulfate ion (SO42–) is blue-colored because it tends to make ionic compounds soluble in water. There are, however, four common exceptions: strontium sulfate (SrSO4), barium sulfate (BaSO4), mercury (II) sulfate (Hg2SO4), and lead (II) sulfate (PbSO4). Two of the cations that form insoluble sulfates (Sr2+ and Ba2+) can be pulled up from the bottom of “Carefully Sliced Bread” and the other two (Hg22+ and Pb2+) can be pulled up from the bottom of “Small, Medium, and Large”. Because of the way the periodic table has been highlighted and labeled, there is a visual symmetry that makes the exceptions to the solubilities of sulfates easily accessible.

Dinner: Three Hotdogs – Small, Medium, and Large

If a compound has one of the blue-colored halide ions (Br–, Cl–, or I–), it will most likely be soluble in water unless those ions are combined with one of the red-colored cations that come below them in the scheme (Ag+, Hg22+, or Pb2+). For example, copper (II) chloride (CuCl2) is water soluble, but silver chloride (AgCl) is not.

A final general statement allows the solubility of ionic compounds made up of ions not involved in the scheme (e.g. the oxide ion, O2–) to be predicted. If a compound does not include one of the blue-colored ions, it is most likely insoluble in water. Therefore, although sodium oxide (Na2O) is water soluble (because it includes an alkali metal), tin (IV) oxide (SnO2) is not.

Conclusion

Almost every assessment in chemistry comes with a periodic table. The periodic table provides a convenient and natural way to think about solubility rules for ionic compounds. Labeling a periodic table in the way described in this article takes seconds, yet it allows information that might normally clutter the mind of a student during an assessment to be displayed in a way that is easily referenced, increasing the likelihood of student success.

Jonathan McClintock (jonathanr244@yahoo.com) is a chemistry teacher at Father Lopez Catholic High School, Daytona Beach, FL.

Chemistry Instructional Materials Teaching Strategies High School