Emerging Connections

Enhancing Environmental Identity: The Ocean Guardian Project

Science education is in the process of a paradigm shift. The goal is no longer recreating a procedure with precision but instead applying science learning in a real-world context. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) use scientific practices to empower a greater understanding of how science plays a role in our everyday lives. The NGSS put environmental issues at the forefront, identifying environmental issues in the standards, raising environmental awareness and recognizing the “role of humans in, with, and of the environment” (Hufnagel, Kelly, and Henderson 2018, p. 750).

The school and home environments, in addition to social context, are crucial in shaping the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) learning ecosystem. The relationships between parent and student, teacher and student, and student to student, as well as students’ roles in the community are especially impactful when considering pro-environmental behaviors. Pro-environmental behavior can be as simple as recycling, though more broadly refers to any conscious behavior to minimize the negative impact of an individual’s actions on the environment. While the middle school classroom may be viewed as the primary context where students learn about and experience science, students’ learning experiences are also heavily influenced by their parents. In addition to affecting learning and academic success, parents also impact the behaviors of their children. Arguably the best predictor for promoting pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors is the influence of role models, peers, and family that care for nature (Darner 2009). Parental involvement is crucial for instilling these attitudes and behaviors.

Because schools have a strong influence in social and environmental contexts, they can enhance parental involvement, which is crucial for middle school–age students when interest in science tends to decline.

The Ocean Guardian Project

My middle school students at Olympic Peninsula Academy (OPA) participated in a stewardship project in the 2019–2020 school year with funds from the Ocean Guardian Grant awarded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Through the project, students went on field trips to local beaches to collect and track marine debris, and monitor water quality. Parents were also encouraged to participate in these field trips. In this article, we explore how one’s environmental identity is formed; the importance of positive role modeling through parental involvement; and how knowledge, experience, and positive affect can facilitate positive environmental identities and pro-environmental behaviors using the Ocean Guardian Project at OPA as a case study.

Located in Sequim, Washington, OPA is an Alternative Learning Experience school, which is a public education opportunity where some, or all, of the instruction is administered outside of a typical classroom, and follows all public education requirements. In the 2019–2020 school year we used funds from the Ocean Guardian Grant to take several field trips to two beach sites in our Dungeness watershed: Port Williams and Dungeness Landing (Figure 1). Parents participating in these field trips were not passive chaperones; they helped catalogue data being collected (in apps and on paper) and encouraged student questioning and inquiry. Before the field trip, parents were encouraged to download Marine Debris Tracker (a waste auditing app) and pHyer (a pH measuring tool), two of the apps we used to collect data. Families were encouraged to use the apps independently of the field trips to see if they noticed any trends in the waste at sites they visited.

The project had specific program goals related to the stewardship of the Dungeness watershed. Using the NGSS standard MS-ESS3-3: Earth and Human Activity as a guide, students learned how human actions can impact the health of the Pacific Ocean ecosystem. This standard focuses on applying scientific principles to monitor and minimize human impact on the environment. We examined the varied landscape—from agricultural lands to private homesteads—and how land use affects the watershed. By engaging in a local project, students drew connections to both the place and the science being conducted, which together help shape environmental identity.

Throughout the duration of the Ocean Guardian Project students

- calculated their carbon footprint with their families using the tools provided by the International Student Carbon Footprint Challenge;

- visited the two sites repeatedly throughout the 2019–2020 school year;

- collected and categorized debris found at the sites;

- measured pH at three different locations at each site (Figure 2) and compared the data longitudinally; and

- collected water samples for the classroom to examine water chemistry, specifically pH and dissolved oxygen.

These activities provided the experience, knowledge, and repeated exposure to these locations that aid in the development of positive environmental identities.

Shaping Environmental Identity

To determine best practices for cultivating positive environmental identities and pro-environmental behavior, it is important to examine what experiences shape an individual’s sense of self-efficacy. As defined by Bandura, Freeman, and Lightsey (1999), self-efficacy is the belief that one is capable of taking the actions required to meet a specific goal. This perception is shaped by an individual’s knowledge, experience, and values, which are inextricably linked. Experiences shape the knowledge that enables an individual to construct meaning of the world, to understand it and its value. This can be seen through Ajzen’s (2011) theory of planned behavior, which has been effectively used to determine pro-environmental behavior by examining environmental attitudes and knowledge (Duerden and Witt 2010). Moreover, the STEM ecosystem is shaped by the social and environmental context, as well as these domains.

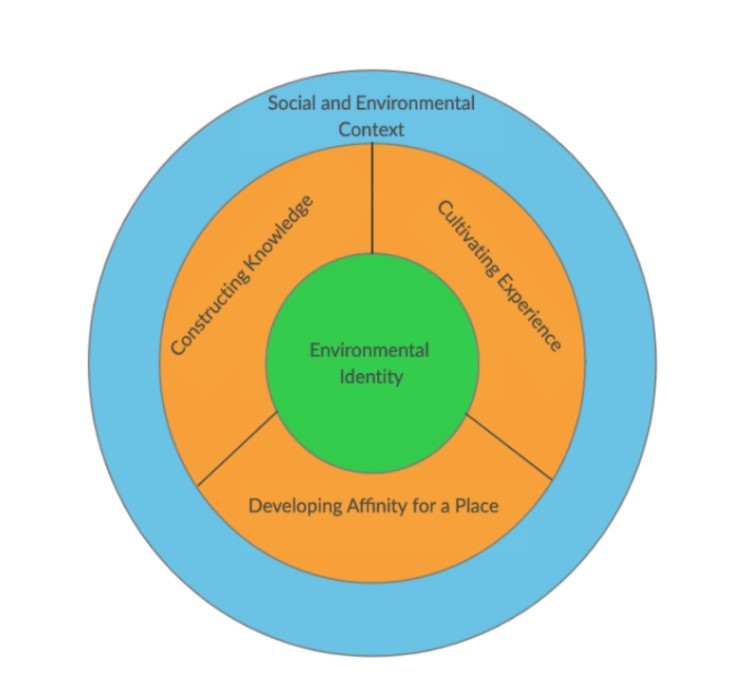

Within the social and environmental context, knowledge, experience, and affinity for place come together to shape an individual's environmental identity and, when combined, can elicit action (see Figure 3). Through repeated experiences and the opportunity to apply knowledge, one develops further connectedness to a place. This enhances one’s personal investment in this place and makes it more likely that pro-environmental behaviors will be adopted. We examine how these attitudes impact behavior and the best motivators to elicit pro-environmental behavior.

Constructing Knowledge and Attitudes

When discussing STEM education, it can be important to differentiate between the formal and informal learning environment, both of which offer valuable learning experiences. Environmental education consists of both indirect (in the classroom) and direct experience (immersed in the environment being studied). These distinctions are important because indirect experiences tend to lead to more cognitively rooted attitudes, whereas direct experiences tend to result in more affective attitudes (Duerden and Witt 2010). Previous studies have shown that while environmental knowledge can be acquired and measured through indirect experience with nature, it does not often impact environmental behavior when there is no opportunity for application (Duerden and Witt 2010). However, when learning takes place in a natural environment, the opportunity to impact attitudes toward the environment—as well as the desire to take care of it—is amplified. These kinds of experiences shape an individual's environmental identity, “which forms when people identify with nature and consider caring for it an important aspect of their self-concept” (Chawla 2009, p. 6). Knowledge is beneficial not only for understanding environmental issues, but for knowing what can be done and instilling the belief that one can take action and achieve the goals they set (Chawla 2009).

To make the Ocean Guardian Project at OPA meaningful and relevant to students and their families, we studied chemistry through the lens of ocean acidification at two locations. In our formal classroom, we studied pH and identified risk factors that might alter the pH of the two sites we were visiting. The two locations are geographically distinct, offering a unique opportunity to engage in a comparative study. While this in-classroom learning was valuable and gave students a basis for understanding the environmental issues, knowledge alone would not be enough to enhance pro-environmental behaviors, so we headed into the field.

Cultivating Experience

Direct experience is one of the most catalyzing determinants of exhibiting environmental behaviors. Darner (2009) found that there were four specific experiences that environmentalists generally shared: (1) they could cite supportive family members or role models who cared for nature, (2) they had fond childhood memories in natural spaces, (3) they had seen the destruction of a treasured natural space, and (4) they had participated in some form of formal environmental education. This indicates how both direct experiences and influential adults can make a difference. Individuals must have the opportunity to learn from an influential adult or peer, and in a natural space to develop the kind of experience that ultimately leads to positive environmental identities.

My goal was to emphasize positive role models by involving parents in the Ocean Guardian project. By engaging parents in field trips and encouraging repeated visits to our sites, I hoped to reinforce a positive relationship with the places where we are stewards. Carson (2017) recognized that children have an innate sense of wonder, but sharing that wonder with at least one adult enables them to discover the mysteries and joys of the natural world. It is through direct contact with nature where we see the biggest benefits in encouraging pro-environmental behaviors (Duerden and Witt 2010). Unsurprisingly, there is a positive correlation between the amount of time spent in natural spaces and the likelihood of pro-environmental behavior (Bogner 1998). Parents and/or influential adults can enhance these experiences by engaging with their child outside and in nature.

Developing Affinity for a Place

Having positive experiences in natural spaces is one of the best ways to enhance affinity toward a particular place, often termed “sense of place” (Kudryavstev, Stedman, and Krasny 2012). Sense of place is defined by the degree of attachment a person has for a place and the meaning that place holds for the individual. This feeling typically gets richer over time with repeated exposure. These visits should be frequent to enhance positive attitudes. Having such direct, positive experiences has been positively correlated with pro-environmental behavior changes (Duerden and Witt 2010). Shifts in attitudes may involve feelings about the environment in general, feelings toward a particular species, or about one’s role in the world. However, research has shown that even those who claim to hold pro-environmental attitudes rarely act in accordance with those purported attitudes (Darner 2009). It is easy to say you feel a certain way, but it is more challenging to act accordingly. Altering everyday practices that we have grown accustomed to can be a challenge.

To enhance environmental identity, the Ocean Guardian Project incorporated elements of the formal classroom, hands-on experience, and sense of place within both social and environmental contexts. By establishing a foundation for knowledge in the classroom, using the tools available to enhance understanding, and having repeated exposure to our project sites, it was my hope that students and their families would develop positive environmental identities and ultimately demonstrate pro-environmental behaviors. Moreover, when parents and students feel compelled to act together because they share a collective sentiment for a place, they keep each other accountable, which fosters positive environmental identities in students and their families.

Adult Influence and Behavior Change

According to Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, behavior is a function of our behavioral beliefs (the ideas behind our behavior), our normative beliefs (those relating to social norms and expectations), and our control beliefs (beliefs relating to our ability, skill, and knowledge and their impact on behavior). This theory suggests that an individual's intention to behave a certain way is especially influenced by the amount of control they perceive themselves to have over their behavior (Duerden and Witt 2010). These beliefs are heavily impacted by a parents' perception of how capable their child is at learning in a given subject area, as well as to what degree parents value that subject (Liou et al. 2019). Perceptions that science has relevance in one’s life and student’s perceptions of their parent’s support for their interest in science are positive predictors for a career in science (Falk et al. 2015).

When parents are involved in the intrinsic value of a given practice, such as encouraging their child to enjoy learning, it can enhance student intrinsic motivation up until the age of nine (Liou et al. 2019). Interestingly, this motivation wanes through the teen years; whether it is due to decreased parental involvement or the impact of social influence is undetermined. While it can be difficult for parents to influence social dynamics, if parental involvement is sustained during the middle school years, we may see enhanced environmental identity.

Self-Efficacy and The STEM Ecosystem

Research indicates that individuals who possess positive environmental identities and interests have an increased likelihood of demonstrating pro-environmental behaviors. Environmental education programs with longer durations are typically more successful in reinforcing environmental identity (Duerden and Witt 2010). In addition, formal environmental education has shown to be more successful in influencing behavior than informal environmental education (Darner 2009). A possible explanation is that formal programs are typically longer and focus on cognitive learning, which can promote affective growth. A student must have a strong sense of self-efficacy to feel empowered to make a change, which can be challenging with middle school students experiencing constant emotional and physical changes during these developmental years.

As a part of the Ocean Guardian Project, my students brainstormed a pledge for Zero Waste Week, where they target a form of waste that they want to eliminate for at least one week. This task was met with resistance from some students who said it couldn’t be done, and others who didn’t think it would make much of a difference. Ultimately, we were unable to participate in Zero Waste Week due to COVID-19. Nevertheless, if an individual’s perceived self-efficacy makes them feel that their actions will have an impact, they are more likely to do so (Bandura et al. 1999). This is why it is so important to set small, manageable goals. Previous studies with children have shown that simple, proximal subgoals are often more motivating than distant, larger-scale goals (Chawla 2009). Nevertheless, a strong indicator of whether someone will act on pro-environmental values often depends on how convenient the action is. Children can easily identify what they think can be done, but they need to be willing to do it.

Parents are integral to the execution of these practices. Parent involvement can be broken into three subtypes: (1) positivity, how they may encourage learning in a specific area; (2) co-activity, how they may participate in their child’s learning; and (3) school-focused behaviors, how they value and encourage academic diligence (Liou et al. 2019). Parents who demonstrate strong involvement in each of these areas positively correlates with students’ sense of intrinsic motivation and value toward the sciences. Not only do students who have parents who participate in their learning have an increased sense of value in these subject areas, but they also ultimately demonstrate enhanced academic achievement and competence.

Simply put, students do not act alone in their resulting behaviors—parental support can have a resounding impact. When a nurturing environment is created between school and home life, students often feel compelled to get others to engage even if they do not believe themselves to be sole agents of change. The environment, when viewed as a whole, can seem a broad and expansive challenge. When individuals know and understand which behaviors are pro-environmental and how to partake in those behaviors, they are more likely to act.

Takeaways From the Ocean Guardian Project

After our class took six field trips, three to each site, parents were given a short anonymous survey through Survey Monkey (see Appendix A in Supplemental Resources). Of the responding parents, 67% had been on at least one field trip, and 73% had returned to one or both of the locations as a family. Several parents said they valued the student-led focus of the program. One parent said, “Kids got to feel involved. They got to choose which direction to go, whether to linger or move fast.” Another parent remarked, “These kids love being involved in decisions, they work better that way.” Parents cited that they enjoyed seeing their child engage in “real and practical science,” as well as “learning about the local environment.” Over the course of the school year, parents noted an increase in “general interest in the why and how nature works.” And “more interest in the environment and the processes of the things around them.”

Not only were students learning about the environment, but one parent highlighted that these experiences showed “the kids how to contribute to their community and the impact they can have.” One parent noted, “My child wanted to return to one of the sites, and asked me to drive him and two of his friends. We made a very fun day trip, exploring the area.” Through the repeated exposure to these places, students demonstrated more excitement “about what they were learning and being outside.” Regardless of socioeconomic status, or level of education, any parent can participate in these experiences with their child. Through repeated exposure, students developed a heightened sense of affinity for these places, and it is my hope that they will become future stewards.

There were some limitations to the Ocean Guardian Project. Not all families have had an opportunity to participate in the field trip outings. Being restricted to the school day makes it difficult for many families to get involved. Despite this limitation, the beach locations were selected based on their accessibility to the community to promote students returning independently with their families. Even for students who weren’t as interested in the data collection, students were happy to be exploring and sharing time outside with their peers. This in and of itself has value, as the experiential component helps develop sense of place.

Encouraging Future Stewards

The most effective experiences to cultivate positive environmental identities take place within the social and environmental context, and are rooted in knowledge, experience, and affinity for place. We cannot care for that which we don't know. The more we learn about and are exposed to natural places, the more positive feelings are reinforced, which helps foster positive environmental identities.

Students who participated in the Ocean Guardian Project had the opportunity to learn about their local ecosystem, the ways in which humans impact the ecosystem, engage in authentic scientific practices, and consider solutions that they as students could achieve. Parents were also involved in these experiences, which helped reinforce the social and environmental context beyond the classroom. Parental involvement is crucial in bolstering not only these experiences but their child’s motivation to learn about the natural world around them. Parents have the capacity to enhance a child’s desire to learn about science, encourage their academic achievement, and promote pro-environmental behaviors. Teacher, parent, and student relationships are crucial to the framework of the STEM ecosystem, reinforcing the value and necessity for integrated science learning.

Middle school families who participated in the field trips at Olympic Peninsula Academy noted an increase in students’ directed learning, interest in science, and positive environmental behaviors after their involvement during the 2019–2020 school year. Moreover, parents reinforced positive environmental identities in their child by engaging with them in environmental activities on their own time. With a strong STEM ecosystem approach, I am optimistic that with careful, longitudinal monitoring, we can work together to sustain interest in science.

Nessa Goldman (goldman@miamioh.edu) is a middle school math and science teacher in Sequim, Washington, and a graduate student at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

citation: Goldman, N. 2020. Enhancing environmental identity: The Ocean Guardian Project. Connected Science Learning 2 (4). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-october-december-2020/enhancing-environmental

Citizen Science Environmental Science Inquiry STEM Middle School Informal Education