Middle School | Daily Do

How Can Cows on the Move Help Rebuild Entire Ecosystems?

Climate Change Crosscutting Concepts Earth & Space Science Environmental Science Is Lesson Plan NGSS Phenomena Science and Engineering Practices Three-Dimensional Learning Middle School Grades 6-8

Sensemaking Checklist

Introduction

In today's lesson, How can cows on the move help rebuild entire ecosystems?, students engage in science and engineering practices to make sense of science ideas about how soil compaction can negatively affect ecosystem services. Next, they analyze data to identify patterns that can help support (or refute) the claim that managed grazing on cover crops - a practice of regenerative agriculture - does not cause soil to become compacted.

This lesson is based on ideas presented in the movie Kiss the Ground. The educational version, Kiss the Ground: For Schools (password: school) is freely available to teachers, educators, schools, and community organizers thanks to a generous grant from the Bia Echo Foundation and Triptyk.

View the How can cows on the move help rebuild entire ecosystems? NGSS table to see the elements of the three dimensions targeted in this lesson.

Materials

- Kiss the Ground: For Schools (password: school)

Clip A 38:03-39:05

Clip B 23:43-25:35

Clip C 33:50-34:46

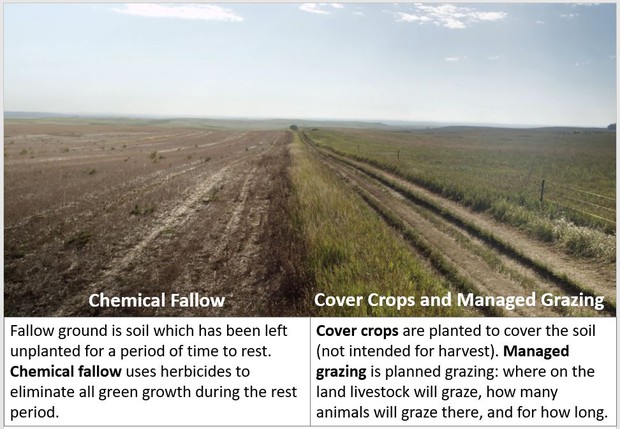

- Chemical Fallow vs Cover Crops and Managed Grazing annotated screenshot

- Accessible area of heavily compacted soil (high foot- and/or bike-traffic area)

- Accessible area of lightly compacted soil (natural, lawn, or landscaped area)

- Soil compaction levels and managed grazing data set

- Soil Compaction Student Handout

- Soil Compaction in Grazed Cover Crop Fields (teacher background)

- Rulers, meter sticks, or measuring tapes (depending on size of soil areas)

- Wire flags (one for teacher demonstration and/or one per student group), optional

- Using a penetrometer to detect soil compaction video clip (1:48–4:15), optional

Experience the Phenomenon

Tell students you were introduced to a phenomenon in the movie Kiss the Ground: For Schools that surprised you, and you're excited to share it with them.

Before you play video clip A, inform students that they are about to hear from Gabe Brown, a regenerative rancher from Bismarck, North Dakota. (You might want to point out Bismarck, North Dakota, on a map.) Share with students that regenerative ranchers use farming/ranching practices informed by scientific principles that (1) repair damaged soils; (2) improve soil-plant interactions; and (3) do no harm to the greater environment. Consider recording this description of regenerative farming/ranching and posting it in the classroom or virtual space.

Consider sharing with students that Gabe Brown uses specialized language that they may not be familiar with; that's okay. Ask students to use context cues to try to capture the big ideas Gabe Brown is communicating to the audience. Play video clip A (38:03–39:05). Ask students to individually "stop and jot" (stop, think, and write about) the big ideas Gabe Brown shared in the video clip.

Next, share the annotated screenshot of Gabe Brown's field and his neighbor's field. Tell students, "Gabe Brown said his neighbor's land had been chemical fallowed, while his own field had managed grazing on cover crops. Both of these practices are intended to rest the soil and reduce erosion. Based on your observation, why might the practice of managed grazing on cover crops be considered regenerative?" Give students time to independently think and record their ideas, then ask them to share their thinking with a partner. As you move around the room, refer students to the posted general criteria for regenerative farming/ranching to help frame their discussion.

Bring students back together and ask them to share their ideas with the class. Student ideas about regenerative farming will likely reveal some prior knowledge (or partial understanding) of interdependent relationships in ecosystems. Students might share the following:

- Chemical fallowing uses herbicides that could harm the environment (wash away, pollute air and water, make animals sick, etc.), while managed grazing on cover crops does not use herbicides.

- When the cover crops/plants die (leaves fall off), they are broken down by decomposers. The plants use the broken-down materials (nutrients) to grow.

- Gabe Brown's fields had more plants, insects, and animals (greater biodiversity) than his neighbor's field.

Tell students, "Now that you've experienced the phenomenon of managed grazing on cover crops helping to rebuild entire ecosystems, I want to share two more video clips that begin to explain how this phenomenon occurs."

Make sure students are aware that many ideas will be shared in the video clips, but they should focus their attention on obtaining and recording information about how managed grazing on cover crops replenishes soil, improves soil-plant interactions, and rebuilds ecosystems. Play video clips B and C.

Assign students to small groups and ask them to share the information they obtained about managed grazing from the video clips. Bring students back together and ask the groups to share their information with the class. Create a record of information shared that should include the following:

- Cover crops include many different types of plants (19!), which "feed" the soil biology. (You may need to tell students that Gabe Brown is referring to the microbes in the soil.)

- Animal hooves push plants into the soil (where decomposers can break down plant matter).

- Animal dung fertilizes the soil (not specifically mentioned, but students may make this inference based on their experience or prior knowledge).

- Animals spend a short amount of time in one place: They don't eat everything, and the plants have time to recover after being knocked down/trampled.

Ask students to review the big ideas they identified and recorded after watching the first video clip, and give them an opportunity to add to or revise their thinking. Consider showing video clip A again to provide students an opportunity to make connections among the pieces of information obtained from the video clips.

Gabe Brown, Regenerative Rancher

Doniga Markegard, Regenerative Rancher

Observe Local Areas of Heavily and Lightly Compacted Soil

Say to students, "Raise your hand if you knew anything about regenerative ranching/farming or managed grazing on cover crops before today." Most likely, very few students will raise their hands (even if they are from an agricultural community). Point out that these ideas are new to many farmers/ranchers, too.

Tell students that while regenerative ranchers like Gabe Brown and Doniga Markegard have shared (and continue to share) their results of managed grazing on cover crops widely, many ranchers and farmers continue to use the same practices they have used in the past. Ask students, "Why might ranchers and farmers continue to use the same practices they have used in the past when managed grazing on cover crops has had positive effects on the land?" Give students time to share ideas with a partner before inviting them to share with the class. Ask students to share an idea their partner shared with the class. Students may share the following:

- What the ranchers and farmers are doing is already working. (Why change?)

- It may cost money to change the way they are ranching and farming.

- Ranchers and farmers may not believe managed grazing on cover crops will work on their land.

Make sure to point out to students that current ranching and farming practices are also based on scientific principles, and agree that ranchers and farmers may continue to use these practices because they are working. Then ask students why ranchers and farmers may not believe managed grazing on cover crops will work on their land. Students will likely say the ranchers and farmers don't have enough data or they need/want more data.

Tell students a group of regenerative farmers in Iowa, called the Practical Farmers of Iowa, shared that farmers they spoke with cited soil compaction as one of their top two concerns about using the practice of managed grazing on cover crops on their own land (see Soil Compaction in Grazed Cover Crop Fields Research Report). Ask students, "What is soil compaction? How might soil get compacted on land where managed grazing on cover crops is practiced?" Students will likely say livestock are heavy and could compact the soil. Other students may disagree; they may recall from the movie that livestock don't stay in the same place for very long. This is acceptable; it is not necessary for students to agree.

Say to students, "I've noticed some areas around our school where the soil is compacted. How might investigating these areas help us understand these farmers' concerns?" Students might say that compacted soil might be bad for the land/soil-plant interactions/ecosystems/etc. Ask students, "What data might we collect? What could we use to make measurements?" Give students independent thinking time to record their ideas, then move them into small groups to exchange ideas with their group members.

Bring students back together and ask the groups to share their thinking. Students may suggest collecting the following data (suggested teacher prompts in italics):

- Amount of plants/count them (Count the number of plants or the different types of plants? Or both? What is another way we might measure the area covered by plants?)

- Amount of insects/count them (Count the number of insects or the different types of insects? Or both?)

- How big the area is/ruler (What could we use if the area is much larger than a ruler?)

- How long the compacted spot lasts/take a picture every day or use a ruler every day (How might we tell if/how much the amount of compaction is changing? How might we measure "compactedness"?)

Bring up measuring the amount of compaction (compaction level) if students do not. Ask how students might quantify the compaction level. If students are struggling, ask, "Do you think it is easy or hard to dig into heavily compacted soil?" Students will say it's hard; this may give students ideas about measuring how easily (qualitative) or far (quantitative) a shovel, trowel, stick, pencil, etc. can be pushed into the ground. Wire flags work well for this purpose.

Ask students, "How could we determine whether the observations we make are caused by soil compaction?" Most students will suggest comparing data between areas of highly compacted soils and areas of lightly compacted soil. Some students will say that the type of soil needs to be the same in the highly-compacted and lightly-compacted areas to compare them.

Provide time for students to collect data from one (or more) highly- and lightly-compacted areas. Follow your school's safety guidelines for working outdoors.

Additional Guidance. If possible, plan to collect data on both dry and wet days. Observations about infiltration and runoff rates (relative) and erosion (via surface water runoff and wind) can contribute to productive discussions about the loss of ecosystem services with increasing compaction levels.

You might ask students to report their data in a shared classroom or virtual space. Ask student groups to identify patterns they observe in the class data. Bring students back together, then ask the groups to share the patterns they identified. Patterns that emerge should include these:

- The more compacted the soil, the higher the runoff rate.

- The more compacted the soil, the lower the infiltration rate.

- The more compacted the soil, the less plants and insects found there (number and type).

- The more compacted the soil, the higher the rate of erosion (moved by runoff on rainy days and wind when the soil is dry)

Ask students, "How would highly compacted soils affect farmland and the people who farm them?" Give students independent thinking time before asking them to share their ideas with a partner. Students may share both physical changes (loss of soil, decrease in number of plants, decrease in biodiversity, etc.) and economic changes (loss of income due to decreased production).

Analyze Soil Compaction Levels and Managed Grazing Records for Two Working Farms

Tell students that a group of scientists, farmers, and ranchers in Iowa designed and conducted an investigation to determine if managed grazing on cover crops had an effect on soil compaction levels (see Soil Compaction in Grazed Cover Crop Fields Research Report).

Briefly describe the investigation design for students:

- The investigation was conducted on two farms located in Iowa.

- The same cover crops—a mix of six plant species—were planted on both farms (test area).

- The control area on each farm had no cover crops and no grazing.

- Livestock were penned in one area of the larger test area for a period of 7 to 28 days (varied from season to season and year to year) before being moved.

- Soil compaction levels were measured in both the test areas and control areas at soil depths of 3, 6, 9, and 24 inches using a penetrometer. (Consider showing students a short clip [1:48–4:15] of the Using a penetrometer to detect soil compaction video.)

- The investigation was conducted between 2015 and 2018.

Share the soil compaction levels data (Figures 1 and 2) and managed grazing record (Table 1) with students. Place students in groups of four, then divide the group into pairs. Assign one pair of students the Carney-Kimberley Compaction levels data (Figure 1) and the other pair the Dooley Compaction levels data (Figure 2). Ask students, working in pairs, to identify patterns they observe in their data sets. As you move around the room, ask students the following:

- How does the soil compaction level change with depth in the test area for the year 2015? In the control area for the year 2015?

- Do you observe a pattern between the test area data and control area data for the year 2015?

- Do you observe a pattern in test area data between 2015 and 2018? In the control area data between 2015 and 2018?

- Do you observe a pattern between soil compaction levels in (year) and number of grazing days? Combined weight of animals? (These data are found in Table 1.)

Next, ask student pairs to share the patterns they identified in their small group. Are there any patterns they can identify between their two data sets (Figure 1 and Figure 2)?

Bring the students back together. Ask groups to take turns sharing one pattern they identified until all observed patterns have been shared. Record the patterns in a public space as the groups share. Patterns should include the following:

- Soil compaction levels were similar between the test area and control area in 2015 on both farms.

- The difference between the compaction levels in the test area and control area gradually increased between 2015 and 2018 on both farms.

- The compaction levels were greater (at all depths) in the control area than the test area on both farms (except for 2016 on the Carney-Kimberley farm).

Make a Recommendation to Iowa Farmers

Facilitate a building understanding discussion with students. You might use some or all of the prompts below to guide student discussion:

- What are some of your claims?

- What's your evidence?

- Does any group have evidence to support Group A’s claim?

- What data do we have that challenges Group B’s claim?

- What can we conclude?

Students should conclude that managed grazing on cover crops may cause a decrease in soil compaction levels at all depths. (They may instead say that not using managed grazing on cover crops may cause the the soil compaction level at all depths to increase.)

Ask students, "How would you revise this investigation to produce data that would make you more confident in making the claim that managed grazing on cover crops may cause a decrease in soil compaction levels? Why would you make these choices?"

Finally, ask each student to write a recommendation for Iowa farmers about changing current (non-regenerative) farming practices to managed grazing on cover crops. Tell students to consider their observations from the Kiss the Ground: For Schools (password: school) video clips, the data collected by the class in the highly- and lightly-compacted soil areas near the school, and data from the managed grazing on cover crops investigation conducted by the Practical Farmers of Iowa group as the basis for evidence to support their recommendation. Encourage students to use words, pictures, and/or symbols to communicate their ideas.

Putting the Big Pieces Together

If time allows, play the entire Kiss the Ground: For Schools movie (password: school) to show students how the phenomenon of cover crops and managed grazing helping to rebuild entire ecosystems fits into the larger picture of reversing climate change.

Acknowledgments

KISS THE GROUND: FOR SCHOOLS—available now for free to all schools, students, teachers, and community educators—is a 45-minute-long educational version of the critically praised exo-documentary, KISS THE GROUND, produced and directed by Sundance award-winning documentarians Josh and Rebecca Tickell. KISS THE GROUND: FOR SCHOOLS has new scenes not in the feature film, including a series of person-on-the-street interviews with Rosario Dawson and a scene in which Tony Tenfingers, a Lakota Elder, describes the importance of the once-prevalent buffalo for Native American peoples. KISS THE GROUND: FOR SCHOOLS is also available with subtitles in 18 languages including English Closed Captions, Spanish, Mandarin, and Hindi.