Hot Air Science

By Gabe Kraljevic

Posted on 2019-07-20

I want to demonstrate different states of matter and need activities for third graders for gases.

I want to demonstrate different states of matter and need activities for third graders for gases.

— D., Georgia

It’s hard to teach about something we can’t see!

Here are a few ideas:

Perfumes: Open a bottle of cologne in the room. Students can observe evaporation if you pour some on a dark counter.

Solid room air fresheners: This is a scented material in solid form and, over time, you will see the solid disappear as it sublimates.

“Ghost” in a Bottle: (Have theatrical fun with this.) Refrigerate a large, empty pop bottle before class. Bring it to class, open it and place a coin over the opening. In a few moments you will hear the coin rattling as the gas inside the bottle heats and expands.

Crushing a can: (Practice this demo for safety.) Boil a few mL of water in an aluminum can until steam comes out. Grasp the can with tongs and quickly turn it upside down into a pan of ice water. The steam condenses, emptying the can of a lot of gas. Atmospheric pressure outside is now greater than the pressure inside the can, causing it to crush.

Break a ruler using air: place a wooden ruler half way over the edge of a table. Flatten a full sheet of newspaper across the ruler. A forceful karate chop should break the ruler. The large surface area of the newspaper has substantial atmospheric mass pushing down on it, holding the ruler in place.

Hope this helps!

Image credit: Ken Boyd via Pixabay

I want to demonstrate different states of matter and need activities for third graders for gases.

I want to demonstrate different states of matter and need activities for third graders for gases.

— D., Georgia

It’s hard to teach about something we can’t see!

Here are a few ideas:

Perfumes: Open a bottle of cologne in the room. Students can observe evaporation if you pour some on a dark counter.

Helping Students Take Control of Their Learning

By Cindy Abel

Posted on 2019-07-17

I am responsible for teaching my students how to think, learn, solve problems, and make informed decisions. I firmly believe that science is everywhere and affects all aspects of our daily lives, from the food we eat to the way we communicate. For these reasons, I have always made time for science in my classroom, alongside reading and math, and the more science I taught, the more connections between science and critical-thinking skills I realized.

For many years, my classroom was filled with carefully orchestrated experiments meant to excite and engage my students and guide them toward a preset conclusion. I was a master at linking concepts in science so my students could predict and understand my predetermined outcomes. I alone decided what I wanted them to learn and investigate. My strengths, weaknesses, and questions became theirs; unintentionally, I had eliminated their voice and replaced it with my own. I didn’t realize my flaws until I learned about the instructional shifts in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

When I was asked to travel to Nashville to help pilot a newly written fourth-grade curriculum based on the NGSS, I jumped at the chance. The NGSS were new to me, and I not only hoped to learn more about them, but also to score some free science materials.

Through this piloting opportunity, I learned that my core belief in the importance of science instruction was correct. According to the National Research Council (NRC) of the National Academies, “Understanding science and engineering, now more than ever, is essential for every American citizen.” The NRC’s A Framework for K-12 Science Education also states that “some knowledge of science and engineering is required to engage with the major public policy issues of today, as well as to make informed everyday decisions….In addition, understanding science and the extraordinary insights it has produced can be meaningful and relevant on a personal level, opening new worlds to explore and offering lifelong opportunities for enriching people’s lives.” (NRC 2012)

Although my core beliefs and teaching instincts were correct, my science practices were not. I learned a whole new way of teaching that turned everything I thought I knew about teaching science on its head, and it was all so simple: Let the students take control of their own learning.

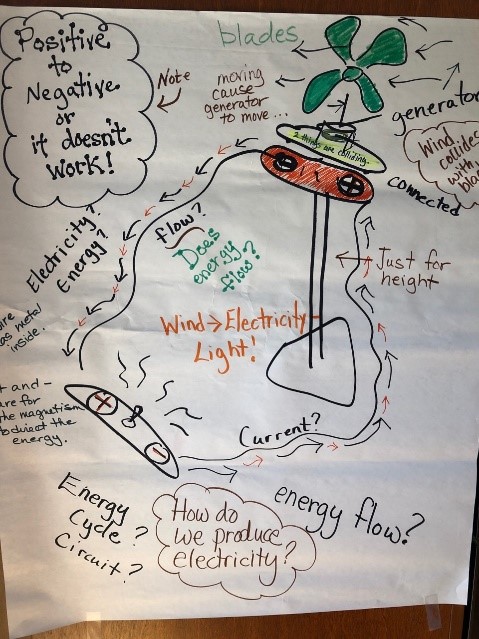

Through the pilot, I was introduced to phenomenon-based teaching as a staple of the NGSS. The use of phenomena and student questions about phenomena are important shifts in three-dimensional learning. I began using anchor models and Driving Question Boards as vital instructional tools in my classroom. These models were not the well-crafted artistic showpieces I had used in the past, the ones I hung in a well-lit area and hoped students referred to on tests. Instead these “new” anchor charts are critical working documents, created with student ideas, that students continually refer to and update throughout the unit of study; these anchor charts chronicle my students’ progression of learning.

Before we begin to create the class anchor model, I introduce my fourth-grade students to an anchor phenomenon, such as the many rock layers of the Grand Canyon or how a windmill can harness wind and change it to light. Students create initial models individually, trying to explain the phenomenon on their own. Next they discuss and edit their work with a small group of peers. Finally, the class comes to a whole-group consensus and creates a class anchor model to explain the mechanism of the phenomenon.

I facilitate this process by using a whole-group discussion format. When one student suggests an addition to the model, classmates give a “thumbs-up” or “thumbs-down” signal to indicate whether they agree or disagree with it. If someone disagrees, we open the floor for discussion until we reach an agreement. As we try to model the phenomenon, students realize they don’t yet have all the information to make sense of what is happening.

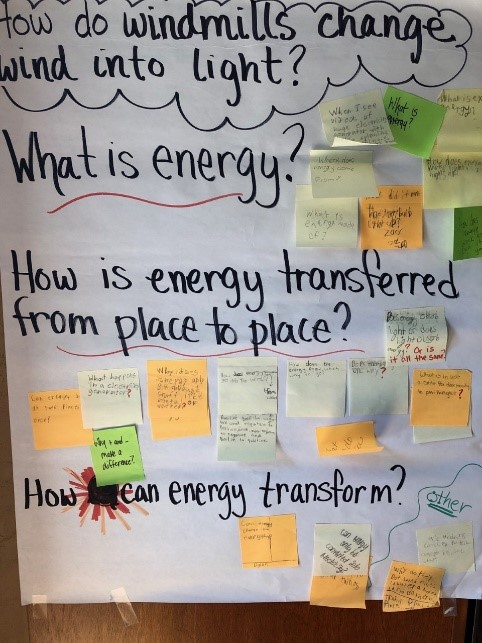

Driving Question Boards (DQBs) are in every module I teach. They are a staple of my NGSS classroom and underscore that student ideas drive the learning. A DQB is a living document that we refer to, update, and add to. On it, kids post their questions, their prior knowledge, and their observations about the anchor phenomenon. The DQB grows with the students’ learning.

Students write questions they have about the anchor phenomenon on sticky notes. We post them on a classroom chart and look for similarities among the questions, ensuring that every student participates and every voice is heard. Next we group the questions into three or four “big” questions that the entire class can investigate further. During this process, as students drive instruction through questioning, they become more engaged and improve their understanding of science as they work to make sense of the world around them.

Throughout the unit, we complete investigations to gather evidence and find answers to our questions. When students have drawn evidence-based conclusions from their investigations, we apply the new information to the anchor model and revisit the DQB to resolve earlier questions and add new questions. We repeat this process until all our questions have been answered and students can make sense of the anchor phenomenon.

My classroom has become more student-centered: Students take ownership of the science concepts they discover and responsibility for the acquisition of new knowledge and understandings. Simply put, my students take control of their own learning. When students go public with their ideas, they are placed in the drivers’ seat, which opens new worlds for them to explore. I empower them to become critical thinkers and prepare them to collaborate with others as they learn to make informed decisions in their everyday lives.

Reference

National Research Council (NRC). 2012. A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Cindy Abel teaches fourth grade at Robert C. Hill Elementary School in Romeoville, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. She has a bachelor’s degree in elementary education from the University of Illinois at Chicago and a master’s in education from National Louis University. Abel resides in Plainfield, Illinois, with her husband and two children.

Note: This article is featured in the July issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

I am responsible for teaching my students how to think, learn, solve problems, and make informed decisions. I firmly believe that science is everywhere and affects all aspects of our daily lives, from the food we eat to the way we communicate. For these reasons, I have always made time for science in my classroom, alongside reading and math, and the more science I taught, the more connections between science and critical-thinking skills I realized.

Next Gen Navigator

A Physics Teaching Approach That Supports Real-World Science by Matt Holsten

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2019-07-17

Traditional physics education can leave many students confused, bored, or without the conceptual understanding of the equations they are required to memorize. I prefer an approach that allows students to use evidence to express, clarify, and justify their ideas so they can form their own equations based on their conceptual understandings. It is much more meaningful and helps them understand how the equation really connects to the concept it models.

It is important that students discover relationships among variables on their own, before they can create a mathematical model of the concept they are studying. Students can use the data they collect in a lab or activity to justify to their teacher and peers why they placed variables in their respective places within an equation—something the 5E Instructional Model supports. The 5E Model leads to greater understanding of science concepts, and it lends itself very well to NGSS implementation. I use the 5E Model as a template for equation discovery in the physics classroom. To show how this can be done in the classroom, I’ll explain how my students engage in each step of the 5E process in an equation discovery station lab for torque—a force that causes an object to rotate.

I begin by engaging students in an activity that catches their attention. To introduce torque, I ask the tallest and shortest students to help me with a demonstration. I ask the entire class to move to the classroom door. The biggest student pushes to open the door at the hinge while the smaller student tries to close it by pushing with a pointer finger by the door handle.

When the door easily closes, I ask students to share with the person standing next to them (while I listen in) their initial ideas as to why the door closed. What was different between Student A’s and B’s push? This exchange is very informal, as it is intended to simply open their minds to the new concept. For safety purposes, I sometimes model the demonstration first, but I always give students the opportunity to try it afterward.

I then give students the chance to explore the topic on their own, with my guidance as needed, by engaging them in conceptual station lab activities. These activities help them determine the values that concepts are directly or inversely proportional to. I set up different activities at each station with a whiteboard or large piece of paper and give each group a different colored marker. My students perform a unique experiment at each station, write what they did on the whiteboard, and record an observation. They cycle from station to station, performing experiments and developing their understanding of the concept.

For a torque lab, I set up stations that include a balancing meter stick, students “fishing” for hooked masses with a meter stick with strings to hook the mass at different points, a PhET Interactive Simulation to demonstrate rotational equilibrium, and a loop of string tied around the pages of a textbook that students attempt to open. All these stations allow students to perform experiments that test the relationship between torque (T) and the variables it depends on: distance from the axis of rotation (r) and the applied force (F). As they complete each station, they write what they did to determine if T is directly or inversely related to r and/or F and what result led them to that conclusion. One of the best things about these activities is their simplicity; you don’t need expensive equipment for your students to be able to do them.

When students have finished the activities, I ask them to bring their whiteboards to the front of the room and read their experiments and results aloud to the class. Student data and thoughts drive the conversation about what the torque concept is directly and inversely proportional to.

I give students a worksheet that lets them organize their thoughts, and when they have completed it, they ask me to “check it.” It’s not important if their ideas are correct at this point, as long as they have logical justification for their thoughts. When students have finished discussing their results with their original groups, they form new groups with at least one person from each of the original groups. My students discuss their final results with their new groups using specific data from the lab, come to consensus on an equation, and justify their thoughts with evidence from the investigations they completed.

After the equation has been formulated, I work with students to extend their knowledge. They typically are proud of the equation they created for themselves, and they understand how the equation actually connects to the real-world concept. I then give them real-world scenarios, and students begin working on practice problems. Calculations and practice problems have their place in the physics classroom, but now that students truly understand the concepts, calculations and practice problems are much more meaningful.

Finally, I evaluate student understanding, and the students evaluate their understanding themselves. I evaluate my students using an open-ended assessment that matches the learning style. Sometimes I use a student-designed Problem-Based Learning lab in which they create their own procedures to model and test a real-world problem. I use the ideas students communicate through their lab report to assess their understanding of the concepts.

Learning physics this way helps students build conceptual understanding, rather than simply learning to plug numbers into an equation. They see it as a mathematical model for a real-world concept. Science classes taught in this way are true to how science is conducted in the real world.

Typically, as students progress through science courses in school, the discovery process is replaced by the “prove this is right” process. But when scientists set out to explain something they don’t understand, they don’t know the results, so why should the way our students develop their understanding of physics be any different?

Matt Holsten is a physics and physical science teacher at Hightstown High School in East Windsor, New Jersey. He graduated from The College of New Jersey in 2016 and has been named one of New Jersey’s Top 30 Teachers Under 30 by the New Jersey Education Association Holsten plans to pursue a master’s degree and eventually a PhD in physics education. He is the proud “fur father” of a two-year-old adopted Chocolate Lab who keeps him very busy.

Note: This article is featured in the July issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2019 National Conference

STEM Forum & Expo

2019 Fall Conferences

Traditional physics education can leave many students confused, bored, or without the conceptual understanding of the equations they are required to memorize. I prefer an approach that allows students to use evidence to express, clarify, and justify their ideas so they can form their own equations based on their conceptual understandings. It is much more meaningful and helps them understand how the equation really connects to the concept it models.

Modeling How Students Can Share Ideas and Make Sense of Phenomena by Aaron Mueller

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2019-07-17

One of the most important steps I take to elicit student ideas in the classroom is to establish a classroom culture that makes students feel comfortable sharing their ideas. I take the time to develop a strong, receptive culture at the beginning of the year, to support students sharing their ideas throughout the year.

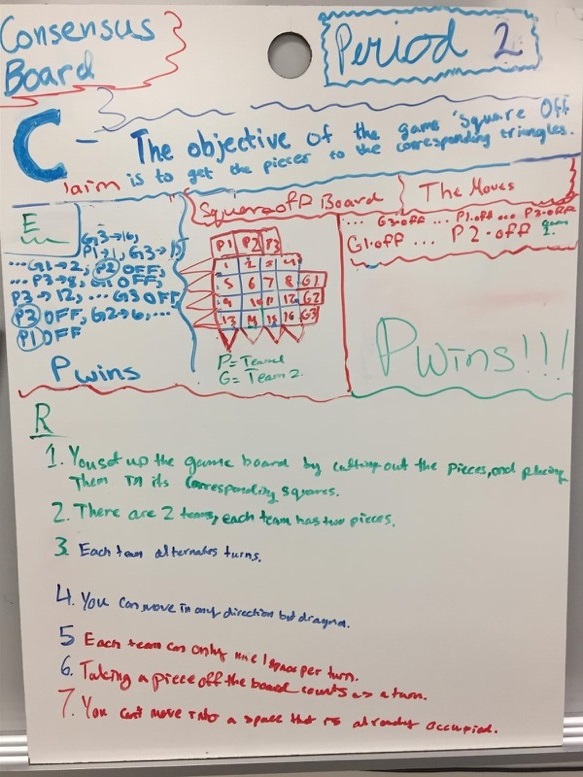

One way I establish a culture that welcomes sharing ideas, thinking, and making sense of phenomena is by capitalizing on students’ natural love of “figuring things out” using a fictitious board game that students don’t know the rules for. I use a game from the American Modeling Teachers Association that students haven’t played. Their task is to make sense of the game board, including game moves and results; figure out the rules; and understand the game’s purpose.

During this process, students tend to become less anxious in the science classroom and rely more on their background knowledge of traditional board games. Many students engage in dynamic negotiations of how they believe the game should be played and consequently lose any fear they may have of sharing ideas in class. They start perceiving themselves as confident defenders of their sense-making. This becomes a model for how students will share ideas and question others’ understanding, and prepares them to engage in sense-making in the context of a phenomenon.

This approach also gives me the opportunity to model with them how they will drive our learning in the classroom, and encourage them to share ideas and negotiate their thinking with the class. When students are comfortable sharing ideas in a low-stakes setting, they are able to transfer these strategies to a phenomenon.

My first unit of study is ecosystems. I use as an anchoring phenomenon the reintroduction of the grey wolves into Yellowstone National Park. I show a video, muting specific dialogue by the narrator that reveals how Yellowstone’s ecosystem changed due to the reintroduction of the wolf. This makes the students use their inferring skills, background knowledge, and personal experiences when visiting Yellowstone to make sense of what was missing. When my students watch the video, they immediately have questions. Now, I have them hooked!

One way I elicit and record students’ questions is by using a Driving Question Board (DQB). Student DQBs are dependent on choosing the right phenomena and framing the phenomena so that students have questions and develop the need to know.

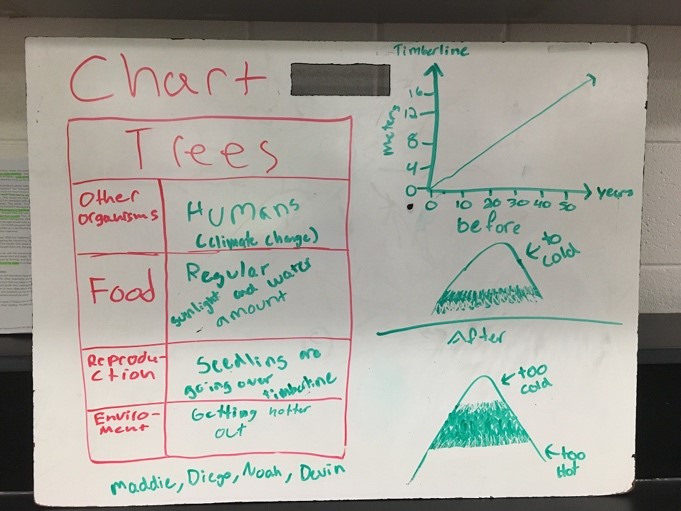

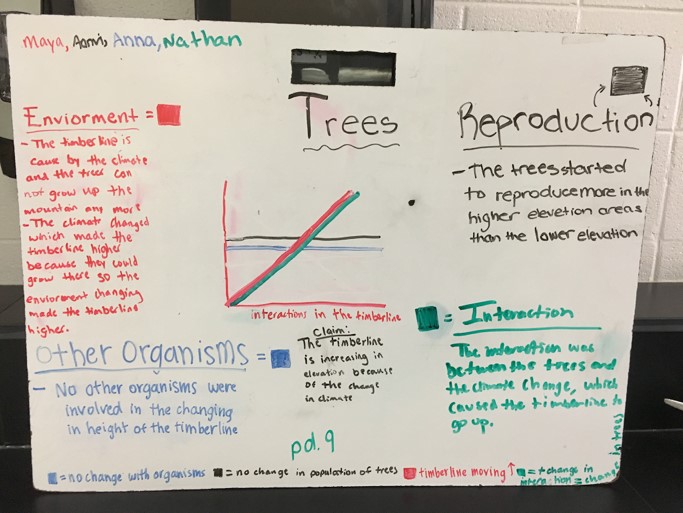

In one lesson, students are presented with three different organisms and explore their interactions with the environment, another organism, or both. Students develop arguments on their whiteboards using the Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning (CER) framework to make sense of how an organism interacts with the environment or another organism. Students compare their whiteboard CERs and negotiate with one another to determine which argument has stronger evidence.

Using the whiteboard empowers students to drive the questioning and sense-making in the classroom. The groups create a class consensus based on the negotiating that took place, and my role is to facilitate and record evidence that leads to the consensus decision while they look to their peers for support.

The process of eliciting students’ ideas, sharing their thinking, and sense-making takes time. As the year progresses, students sometimes challenge me to return to the teacher-driven learning process. If this happens, we play another fictitious game to help them develop a more positive mindset about sharing their ideas and sense-making without first having the science content. The best part is students realize and appreciate midway through the year the value of making sense of what they are experiencing instead of just being given or told what to learn. You can see the students’ willingness to take more risks in sharing their thinking as the year progresses.

How do you begin a school year, a new unit, and/or a lesson to encourage students to share their ideas or thinking? How do you feel about the students “driving” the conversations or negotiations? Each new year, unit, and lesson is different for each student. I would love to hear from you about how you have developed a classroom culture of students sharing their thinking and making sense of phenomena.

Aaron Mueller has taught science for 19 years at Scullen Middle School in Naperville, Illinois. He is a member of the Achieve, Inc., Peer Review Panel; a member of the NSTA Cadre for facilitating professional development in three-dimensional instruction and assessment; and a workshop facilitator in Middle School Science Modeling with the American Modeling Teachers Association (AMTA). In addition, Mueller was a finalist in the Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching for Illinois in 2017. He enjoys spending time with his family, coaching track and field, and enjoying the great outdoors.

Note: This article is featured in the July issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2019 National Conference

STEM Forum & Expo

2019 Fall Conferences

One of the most important steps I take to elicit student ideas in the classroom is to establish a classroom culture that makes students feel comfortable sharing their ideas. I take the time to develop a strong, receptive culture at the beginning of the year, to support students sharing their ideas throughout the year.

Brief

Shared Measures for STEM and Science Learning Through the ActApp

Connected Science Learning July-September 2019 (Volume 1, Issue 11)

By Matthew A. Cannady and Kalie Sacco

Many formal and informal science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) learning programs want to understand the impact their work has on learner outcomes. This can be difficult, especially in informal settings (e.g., afterschool programs, museum exhibits) that have limited resources to develop measures for the outcomes of interest. Additionally, several programs may be targeting the same outcomes but use different tools to measure them, leading to inconsistency in understanding impact across the STEM learning field.

Shared measures (i.e., instruments that can be used by multiple organizations to evaluate performance and track progress toward goals) and focusing on contiguous outcomes can help overcome those obstacles (Hanleybrown 2011). A project from the Lawrence Hall of Science (the Hall) at the University of California, Berkeley, called ActApp, enables researchers, evaluators, and program leaders to use highly vetted, shared measures of learners’ likelihood of success in future STEM learning experiences.

For nearly a decade, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh, the Hall, and other institutions have been studying the concept of learning activation. Learning activation is defined as “A state composed of dispositions, practices, and knowledge that enables success in proximal learning experiences” (Activation Lab 2019). This team has developed a set of instruments—including surveys, observation guides, and interview protocols—that measure dimensions of STEM learning activation (fascination, values, competency beliefs, scientific sense-making [for science learning], and innovation stance [for STEM learning]); success (choice preference, engagement and perceived success, and more); and covariates (demographics, home resources, and family support for learning). These tools have been developed via research studies involving thousands of students and have been used in dozens of research studies and program evaluations (primarily on learners ages 6–14).

In 2013, with support from the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Hall developed a toolkit that granted greater access to these tools. Dubbed the ActApp, the toolkit includes access to many of the survey and observation tools, as well as an introduction to using them. Users of the toolkit have the benefit of well crafted and highly vetted research instruments, as well as the option of receiving technical assistance and support from the Hall team as consultants or research partners. Since launching the ActApp, the toolkit has been used in partnership with the Hall by the Girl Scouts of the USA, FIRST Robotics, and the San Francisco Unified School District (among others), and independently by programs around the world—from Turkey to the Philippines, across a wide range of learning settings and environments.

The ActApp is free to use, and can be accessed via www.activationlab.org. As of summer 2019, the Hall is offering a professional learning session for evaluators, researchers, and program leaders to dig into the research behind Activation and the most effective use of the toolkit. For more information about that—including how to participate in an upcoming session–please e-mail info@activationlab.org.

Matthew A. Cannady (mcannady@berkeley.edu) is research group director at The Lawrence Hall of Science, University of California, Berkeley, in Berkeley, California. Kalie Sacco (kaliesacco@berkeley.edu) is coordinator for special initiatives, director’s office, at The Lawrence Hall of Science, University of California, Berkeley, in Berkeley, California.

Editorial

Practical Program Evaluation

I love data—especially when used to look at learning experiences and figure out what’s working, what isn’t, and what to do next. Not surprisingly, then, I’m quite excited about this issue of Connected Science Learning, which is all about Practical Program Evaluation. The choice of the word practical in this issue’s theme is intentional. Program evaluation takes time, and time is valuable. Educators have a lot of work to do before thinking about evaluation—so, if they are going to do it, it had better make a difference for their work.

Throughout my career I’ve seen how powerful program evaluation can be when it is done well. For example, a few years back I was project director for a program called STEM Pathways—a collaborative effort between five organizations providing science programming for the same six schools. Much about our program evaluation experience sticks with me: how important it was to involve program staff efficiently and effectively in evaluation design, implementation of findings, and interpretation to decision-making—and how they were empowered by being part of the process; how program evaluation led us to discover things that were surprising and that we would not have otherwise learned; and how the data-informed program improvements we made led to better participant outcomes and program staff satisfaction.

I’ve also seen program evaluation done poorly—such as when it only tells you what you already know, when the information collected isn’t particularly useful for decisions or improvements, or when it fails to empower program staff. We’ve probably all been there at one time or another. But how do we avoid making those same mistakes again?

In my experience, program evaluation that provides utility and value to program developers and implementers by default also satisfies stakeholders. Frankly, if your program evaluation isn’t used for anything more than grant reports, you might want to rethink what you’re doing. Utilization-focused evaluation, an approach developed by evaluation expert Michael Quinn Patton, is based on the principle that evaluation should be useful for its intended users to inform decisions and guide improvement. Patton reminds us to reflect on why we are collecting data and what we intend to use them for—to make sure that conducting the evaluation is worth the time of the people who will implement it, as well as of the program participants who are being evaluated.

The good news is that there is no need to start from scratch. There are many research-based tools and practices to learn from and use, and you will learn about many of them in Connected Science Learning over the next three months. Join us in exploring case studies of program evaluation efforts as well as helpful resources, processes, and implementation tips. You’ll also find articles featuring research-based and readily available tools for measuring participant outcomes and program quality. I hope this issue of Connected Science Learning inspires your organization’s program evaluation practice!

Beth Murphy, PhD (bmurphy@nsta.org) is field editor for Connected Science Learning and an independent STEM education consultant with expertise in fostering collaboration between organizations and schools, providing professional learning experiences for educators, and implementing program evaluation that supports practitioners to do their best work.

Finding Partners for Elementary Science

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2019-07-16

Guest blog post by Wendi Laurence and Laura Cotter

One of my favorite things is discovering new people who can become partners in elementary science programming. While sometimes it is very hard to find those amazing partners; this is a short story about stumbling into one of those partnerships.

A few years ago when I was a STEAM Coordinator at a focus school, I was crawling around on the floor helping students with a Rube Goldberg project. Discovery

Gateway Children’s Museum had an educator onsite working with another age group. Luckily, Laura Cotter the Outreach Education Senior Manager, dropped in.

When she saw the machines the students were building, Laura asked to come in and learn more. It was one of those educators moments when you know you see someone who is all about students learning. She thought it was pretty cool to see the new

STEAM projects taking place and that I was crawling around working with students. I

figured she rocked because she came in and immediately talked to the students –

instead of standing to the side and talking with adults. The conversation after class was one of those where lots of ideas get written down, tons of energy flows and you connect about what might be in science education.

I discovered she was a chemistry major and had worked for years in the pharmacy field. When she decided to take a career swerve, she found the perfect fit at

Discovery Gateway Children’s Museum (DGCM). She was able to merge her love of science, teaching, and an amazing ability to create and manage programming. As we talked, I found out that the DGCM has an amazing professional development program for 5th-grade teachers to learn to teach chemistry. When they have completed the training, they are provided with a curated teaching kit to take back to their classrooms. As a small school just getting rolling with STEAM programming, this was a

great opportunity. From then on, our 5th grade team had great training, materials, and an outreach program that came to school and provided a facilitated chemistry lab experience every year.

A few more conversations into our partnership meant DGCM discovered that I had a

special interest in creating early childhood STEAM learning experiences. Our school became a pilot site, first for their new kindergarten physics curriculum and later piloting components of a professional development program for kindergarten physics.

We partnered to bring museum outreach to different grade levels and connected on field trips, curriculum, children’s literature, and even school gardening. This spring we presented together at the NSTA Elementary Extravaganza in St. Louis.

One of the highlights of our work was being accepted as a team to attend the U.S.

Department of Education’s Teach to Lead program in Nashville, Tennessee. Our team,

a kindergarten teacher, museum educator and STEAM Coordinator, focused on creating a professional learning community centered on supporting early childhood STEAM. A

group of educators is now meeting as a learning community and some members of the team presented together at the Utah Science Teachers Association this winter. The team was just accepted to present at the regional NSTA meeting in Salt Lake City this fall.

Museum/School partnerships can add depth to education programming. Some of our

tips for creating a successful partnership include:

- Value the learning that takes place in both venues and create a bridge between educators in both settings.

- Share resources: references, materials, lessons and share them in places like the NSTA Learning Center where others can access them.

- Learn together: attending conferences together and with other educators has helped increase our network of support for elementary science and museum/school partnerships.

- Get Involved Together: We both support several associations as we are all interested in growing science education opportunities for all students. Create a community: Invite others to join in the fun!

Wendi Laurence, Ed.D. is the founder of Create-osity and currently serves as NSTA

District XIV Director. She is a former STEAM Coordinator and NASA Curriculum

Specialist. Her career is dedicated to vision that: No dream be deferred and no potential unrealized. Follow her on Twitter @createosity

Laura Cotter is the Outreach Education Senior Manager at Discovery Gateway

Children’s Museum. She has a degree in chemistry from the University of Utah. She

serves on the Board of the Utah Science Teachers Association, on the NSTA committee

for Research in Science Education.

Guest blog post by Wendi Laurence and Laura Cotter

One of my favorite things is discovering new people who can become partners in elementary science programming. While sometimes it is very hard to find those amazing partners; this is a short story about stumbling into one of those partnerships.

What’s Your Story?

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2019-07-16

Guest blog post by Anne Lowery

As the traditional school year winds down, it is time to bring explorations to an end or at least to a good stopping place. One of the best ways to signal an end or a transition is through science storytelling.

This approach has many of the science and engineering practices embedded into it, including but not limited to:

Analyzing and Interpreting Data

Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

Science storytelling is also an opportunity to turn study into action and have your students work to improve their own community as they tell a story. The possibilities are endless. Your students could write a story from the perspective of the researcher (themselves), or tell the story from the perspective of the subject of the exploration. They could also use their exploration as a tool to change actions in the community. They can write a song, create a letter campaign, design a video, or talk to community leaders.

By revisiting their work in a slightly different format, they solidify their own learning and begin to see how different learnings are interconnected. By writing it in a fictional format, with characters, students can reach people’s emotions– a surefire way to improve the odds of people remembering.

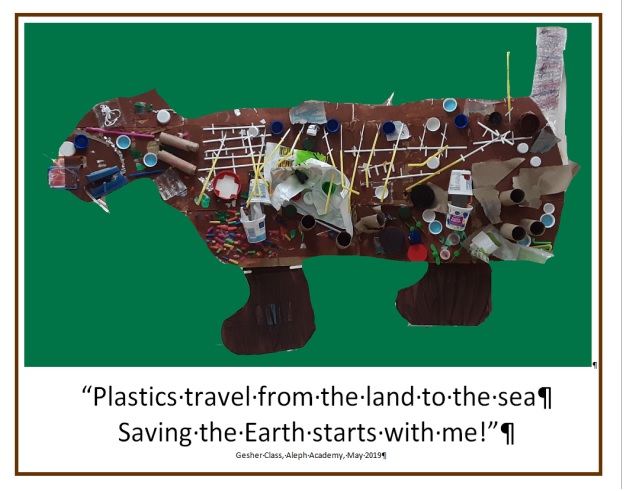

As an example, my students have been studying mountain lions and habitats this year. They noticed that land pollution is a problem with mountain lions, among other land animals. My students decided to focus on using their mountain lion knowledge to create a mountain lion out of trash. Then they wrote a simple chant to go with the mountain lion because, said one of my students, “everyone remembers things better if it’s a song.”

Another student pointed out we needed to write a story to go with our trashy mountain lion. As that student points out, when people imagine themselves in stories, they remember those stories.

Science storytelling has the potential to make your students’ research available to the public as well as having your students use their work to examine a real-world problem they have identified. Through such storytelling and action, your students leave your class not only with knowledge gained during the year but also with the mindset that they are scientists too.

What story are your students going to tell today?

This is a poster created from a 3D art installation created by PreK students. The shape of the mountain lion emphasizes the pollution threat to land animals. The plastics inserted through and covering the cardboard not only represent specific body parts of the animal but also are created from plastics commonly found on land.

Anne Lowry is a preK teacher at a Reggio inspired school in Reno, NV. Her students love to tell stories while discovering and enacting the science and engineering principles!

Guest blog post by Anne Lowery

As the traditional school year winds down, it is time to bring explorations to an end or at least to a good stopping place. One of the best ways to signal an end or a transition is through science storytelling.

This approach has many of the science and engineering practices embedded into it, including but not limited to:

Analyzing and Interpreting Data

Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Ask a Mentor

Emoji Chemistry

By Gabe Kraljevic

Posted on 2019-07-13

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

— M., Maryland

I find it useful to demystify why we use chemical equations.

A chemical equation is simply a communication tool. It similar to using emojis in place of writing words. Instead of emojis, chemists use a periodic table and other standard symbols to communicate what is happening when particles of matter interact. Every scientist in the world knows this shorthand, overcoming language barriers. It is the language of chemistry.

Just like when learning a language, students need to learn basic vocabulary. Before teaching chemical equations, review some basic terminology: atoms, molecules, chemical change, and chemical formulas. Then move on to teaching the notations used in writing out a chemical equation.

A chemical equation is a “recipe” with ingredients, instructions, and expected results. Many recipes have the same ingredients, but the proportion of each determines whether you get a pancake, scone, or loaf of bread. Likewise, a balanced chemical equation gives the exact proportions of reactants to create the expected products. There are actually more details in a chemical equation than a recipe—the symbols indicate exactly how the atoms rearrange, form new bonds and create new products.

In addition to searching NSTA’s The Learning Center, resources at these sites can help teach chemical equations:

American Chemical Society

American Society of Chemistry Teachers

PhET Colorado Simulations

Hope this helps!

Image credit: Chemical & Engineering News

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

— M., Maryland

I find it useful to demystify why we use chemical equations.

Ed News: How to Engage All Students in STEM

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2019-07-12

This week in education news, CTE pathways prepare students for the rigors of STEM careers by giving them foundational skills and allowing for a broader interpretation of STEM; new report finds that 32% of teachers with one year or less of teaching experience have a non-school job over the summer break; study finds that the home literacy environment may influence the development of early number skills; and teachers around the world are using virtual reality to overcome barriers of physical distance and give their students a first-person view of the changes scientists are observing in remote areas.

How to Engage All Students in STEM

Early in their school careers, students see STEM pathways as desirable but then change their minds: 60 percent of high school students who start out interested in STEM careers lose interest by their senior year. And too many of those who are interested do not have the skills that are needed: A study by the Business-Higher Education Forum found that only 17 percent of high school students are both interested in STEM and proficient enough in math to succeed. Read the article featured in Education Week.

About One-In-Six U.S. Teachers Work Second Jobs – And Not Just in the Summer

Classes have ended for the summer at public schools across the United States, but a sizable share of teachers are still hard at work at second jobs outside the classroom. Among all public elementary and secondary school teachers in the U.S., 16% worked non-school summer jobs in the break before the 2015-16 school year. Notably, about the same share of teachers (18%) had second jobs during the 2015-16 school year, too, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Read the article by the Pew Research Center.

Preschoolers Who Practice Phonics Show Stronger Math Skills, Study Finds

Young children who spend more time learning about the relationship between letters and sounds are better at counting, calculating, and recognizing numbers, a new study has found. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Report: More States Pursuing Innovative Assessment Models

Giving interim student assessments for accountability purposes — instead of waiting until spring when it’s too late for teachers to adjust their instruction — could “discourage weeks of pretest preparation” and provide schools with more useful feedback. But there might also be resistance to shifting curriculum and pacing during the school year, and teachers would need support in using the results. That’s one of the topics covered in a new “State of Assessment” report from Bellwether Education Partners. Read the brief featured in Education DIVE.

Elementary Education Has Gone Terribly Wrong

In the early grades, U.S. schools value reading-comprehension skills over knowledge. The results are devastating, especially for poor kids. Read the article featured in The Atlantic.

Virtual Field Trips Bring Students Face-To-Face with Earth’s Most Fragile Ecosystems

Teachers say first-person environmental experiences engage learners and foster empathy. Read the article featured in The Hechinger Report.

Requiring School to Teach Climate Change Risks Backlash in Oklahoma

Melissa Lau is preparing for the coming school year. She teaches 6th grade science in Piedmont, just northwest of Oklahoma City. Lau says she has been educating her students about the connection between fossil fuel combustion and climate change for three years, though she isn’t required to. Oklahoma’s K-12 science standards are based in part on the Next Generation Science Standards, national guidelines developed in 2013 that recommend teaching the concept in sixth grade, but Oklahoma left it out. Read the article featured on KOSU.org.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

This week in education news, CTE pathways prepare students for the rigors of STEM careers by giving them foundational skills and allowing for a broader interpretation of STEM; new report finds that 32% of teachers with one year or less of teaching experience have a non-school job over the summer break; study finds that the home literacy environment may influence the development of early number skills; and teache