Redesigning the Science Fair

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2018-07-01

For the STEAM Fair at Doane Academy in Burlington, New Jersey, upper-school students “complete projects in any field as long as they [relate] in some way to science concepts,” says Michael Russell, STEAM coordinator and mathematics and science department chair. Photo by Jack Newman, director of communications, Doane Academy.

Schools and teachers are transforming traditional science fairs into events incorporating science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) or STEAM (STEM plus Arts). At Lake Washington Girls Middle School in Seattle, Washington, for example, “we have transitioned [to] a Public Health STEAM Fair [in which seventh graders] identify a public health issue in our community, research the issue, develop a question and design a research procedure, then conduct statistical analysis to help them explain their data. Lastly, students present their research to [public health]…experts in the style of a conference,” says Christine Zarker Primomo, STEAM teacher.

“The curriculum in seventh-grade science is biology, so public health works great. But the bigger piece is that it [connects more] to citizen science. Public health is super broad and has a lot of connection to students’ lives,” Primomo observes. In addition, “[s]cience and social justice come together [for students] because their research can impact their community.”

She works closely with the math department because “they teach statistical analysis. [For their project,] students have to collect 30 data points…Students are more motivated to learn about standard deviation when it’s their own data,” she maintains. Local public health department staff provide data sets.

Students collect data via surveys and activities like collecting cigarette butts from nearby water bodies to study their effects on water, for a project exploring the effects of air quality on water quality, Primomo explains. For a project focusing on human sugar consumption, “students had test subjects and created a form requesting permission to collect data from them,” she recalls.

During the fair, students present a slideshow about their research to their families and judges from the public health community. Primomo grades students on their questions, procedures, data analysis, graphs, and presentations.

Doane Academy in Burlington, New Jersey, transitioned to a STEAM Fair because “we [decided] to celebrate student innovation and collaboration across all grade levels with a fair that permitted them to complete projects in any field as long as they related in some way to science concepts,” says Michael Russell, STEAM coordinator and mathematics and science department chair. “We wanted to motivate [students] to use the engineering design process more organically, [with the] idea that the science department isn’t the only anchor for that,” he adds.

Doane now holds a STEAM Fair because the science department found “students who thrive in science do elaborate, cohesive projects, while mid-tier students and students struggling in science find shortcuts and don’t do original work…We wanted to not just apply standards, but also have students do purposeful tinkering, driven by their passions and struggles,” Russell explains. “We made the fair a core part of our curriculum” because when students worked on projects at home, they tended to receive either “too much help from parents or none,” he contends.

Upper-school students can work with any teacher or community member to develop a product of their choice. One student wrote a book of science-related poetry that informed readers about mental health issues. Another wrote short stories about bug anatomy and behavior and illustrated them with photos. “A really cool thing is that our science kids haven’t lost the opportunity to do hard-science projects,” Russell emphasizes.

Introducing Engineering

Seventh- and eighth-grade science teacher Samantha Rudick of Northvale Public School in Northvale, New Jersey, was asked to redesign the seventh-grade science fair to include the engineering design process (EDP). “I [also] came up with [the idea of having] a theme,” she notes. Last year, students were told they were stranded on an island and had to create things to help them survive. This year, she told students they were living in a town with a polluted environment and had to use recycled or reusable materials to create games for a carnival that would raise funds for their town’s new recycling center.

“We did a unit on reusable versus nonrenewable materials…[Students] had to distinguish between [reusable and nonrenewable materials] to create their games,” she explains.

Students developed game prototypes and continued testing and improving them before the fair. They also created an interactive button apparatus that fair attendees could push to begin a presentation. “Some groups’ buttons were electric, [while others] used a sound-making device,” Rudick relates.

In addition, students had to make videos of their games and create a poster board showing every step of the EDP, illustrated with photos. “In their presentations, they had to explain their [EDP] without looking at their poster board,” she points out.

“The [school’s] administrators said this was the best science fair they’d ever seen,” Rudick reports.

Virtual Fairs

“We now participate in a Science/Engineering Fair, and everything is virtual,” says Laura Mackay, science coach and STEM liaison at Ed White Elementary E-STEM Magnet School in El Lago, Texas. “Students complete either a science fair investigation or engineer a design to solve a problem” and create a PowerPoint presentation, she explains.

Science fair participation had declined because “it wasn’t required, so more parents opted out. We decided to take the parents out of the process, and technology allowed this,” she relates.

Science fair boards were no longer needed, “which was really hard for some parents and teachers,” she reports. “The boards were flashy, but they didn’t emphasize the data.”

Using PowerPoint “meets the tech part of STEM,” Mackay contends, because students become highly proficient in it. “We’re modeling what the world is like now [and teaching] lifelong skills,” she adds.

“Science is still in there because students are analyzing data to see if their design will work,” Mackay points out. Past projects have explored solutions to problems like how to go fishing with minimal equipment and how to keep a soda cold using a wet towel in the freezer.

“Sometimes the finished project isn’t as amazing, but it’s all student-driven. It equaled the playing field on the judging part” because not all students have access to technology, “so we provide it to everyone,” she observes.

The judges appreciate that the judging is done virtually because “they don’t have to come here [to do it],” she reports. Students are only graded on participation because “[h]arsh grading killed the love of science fair [in the past],” she asserts.

“[Now we can] see what kids are really capable of doing,” instead of what parents do, Mackay concludes.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

For the STEAM Fair at Doane Academy in Burlington, New Jersey, upper-school students “complete projects in any field as long as they [relate] in some way to science concepts,” says Michael Russell, STEAM coordinator and mathematics and science department chair.

Packaging Design, Grade 6: STEM Road Map for Middle School

Commentary

“When You Walk Into This Room, You’re Scientists!”

How you can promote positive, science-linked identities for all your students

By S. Elisabeth Faller

Teaching Teachers

Breathing New Life Into Elementary Science Preservice Teacher Education

Science and Children—July 2018 (Volume 55, Issue 9)

By Taylor J. Mach and Mandy M. Mach

Engineering Encounters

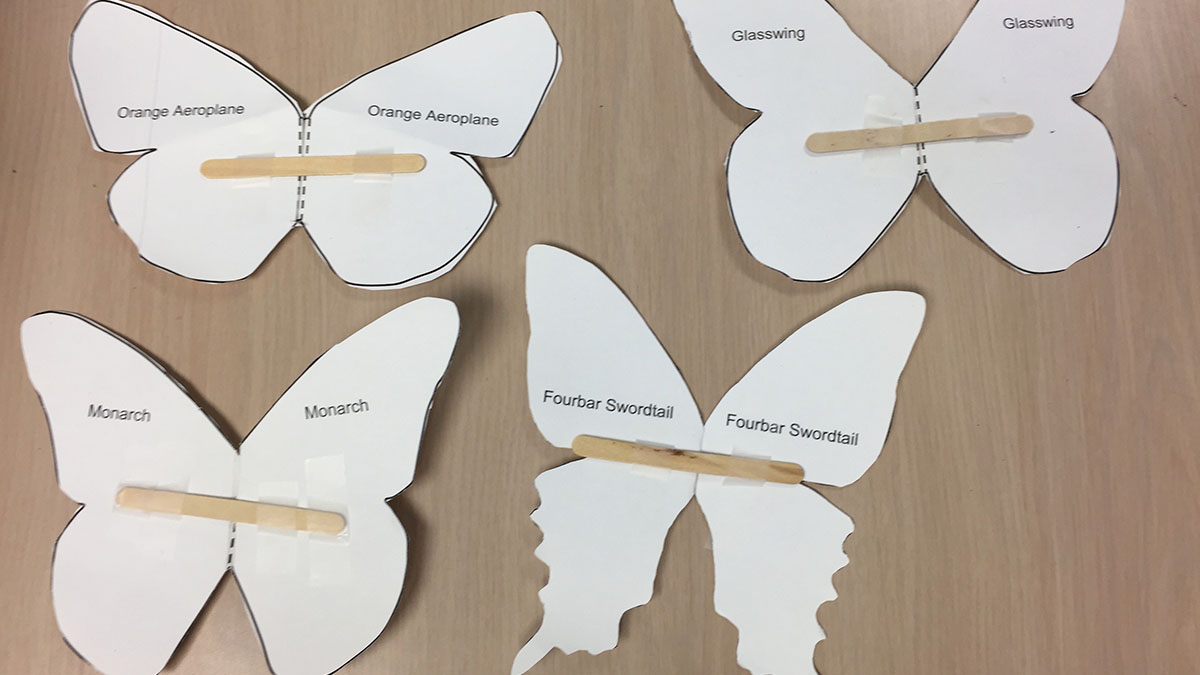

STEM-ify Me: It’s Elementary! Designing Butterfly Wings

Fifth graders’ investigations and design of model butterfly wings with the maximum lift force.

The Early Years

Engaging Children in Multidisciplinary Learning Centers

Science and Children—July 2018 (Volume 55, Issue 9)

By Peggy Ashbrook

The Power of Assessing: Guiding Powerful Practices

Ed News: How Maker Education Supports English Language Learners In STEM

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2018-06-29

This week in education news, President Trump proposes merging the Education Department with the U.S. Department of Labor; new report found that a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded initiative did not improve student performance; teacher shortage becoming a growing concern in Hawaii; Career and Technical Education Bill approved by the Senate education committee; Mattel unveils new Robotics Engineer Barbie; California budget allocates nearly $400 million for science and math education, but not teacher training; NCTM issues a call to action to drastically change the way math is taught so that students can learn more easily; and a new study shows that eighth-grade science teachers without an educational background in science are less likely to practice inquiry-oriented science instruction.

How Maker Education Supports English Languages Learners In STEM

What is the best way to teach STEM to students who haven’t mastered English? Some educators believe the answer lies in maker education, the latest pedagogical movement that embraces hands-on learning through making, building, creating and collaborating. Read the article featured on Gettingsmart.com.

Trump Officially Proposes Merging U.S. Departments of Education, Labor

President Donald Trump wants to combine the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Labor into a single agency focused on workforce readiness and career development. But the plan, which was announced during a cabinet meeting last week, will need congressional approval. That’s likely to be a tough lift. Similar efforts to scrap the nearly 40-year-old education department or combine it with another agency have fallen flat. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Gates-Funded Initiative Fell Short Of Improving Student Performance

A Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded initiative designed to improve student achievement by strengthening teaching did lead to using measures of effectiveness in personnel decisions, but did not improve student performance, particularly that of low-income minority students, according to a new report from the RAND Corporation. Read the article featured in Education DIVE.

Teacher Shortage Becoming A Growing Concern In Hawaii

The number of Hawaii teachers quitting their jobs and leaving the state is becoming a growing concern. The state’s high cost of living and low salaries are among the factors driving away Hawaii teachers. Department of Education employment reports show that 411 teacher resigned and left the state in 2016-17, up from 223 in 2010. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Bipartisan Career And Technical Education Bill Approved By Key Senate Committee

The Senate education committee agreed unanimously via voice vote Tuesday to favorably report a bill reauthorizing the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act to the full Senate. The Senate version, the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act, would revamp the Perkins law, which Congress last reauthorized in 2006, by allowing states to establish certain goals for CTE programs without getting them cleared by the secretary of education first. However, it requires “meaningful progress” to be made towards meeting goals on key indicators. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Tiger Woods Wants To Level The Playing Field In Education One Child At A Time

Opened in 2006, the Learning Lab is the backbone of Tiger Woods’ goal to provide kids a safe place to learn, explore and grow. The Lab offers students from low-income households and underfunded schools a variety of classes in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math). Read the article featured in USA Today.

Barbie Can Now Add ‘Engineer’ To Her Resume

Mattel launched Robotics Engineer Barbie on Tuesday, a doll designed to pique girls’ interest in STEM and shine a light on an underrepresented career field for women, the company announced. The new doll joins a lineup of more than 200 careers held by Barbie, “all of which reinforce the brand’s purpose to inspire the limitless potential in every girl,” Mattel said in a statement. Read the article featured in NBC Los Angeles.

State Budget Has Nearly $400 Million For Science, Math Education – But Not Teacher Training

Science education got a boost in the 2018-19 state budget, but the plan stops short of funding training for teachers in California’s ambitious new science standards — something education leaders had been pushing for. The budget, which the Legislature approved this month and Gov. Brown signed Wednesday, includes a $6.1 billion increase in funding for K-12 schools. It calls for nearly $400 million for programs promoting science, technology, engineering and math education, ranging from STEM teacher recruitment to after-school coding classes to tech internships for high school students. Read the article featured in Ed Source.

Education Bill That Omits Trump Merger Plan, Boosts Spending Advances In Senate

Legislation that would provide a funding boost for disadvantaged students and special education was approved by the Senate appropriations committee on Thursday. The fiscal 2019 spending bill also does not include the Trump administration’s proposal, unveiled last week, to merge the Education and Labor Departments into a single agency called the Department of Education and the Workforce. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Teachers Test New Approach To High School Math

Math understanding at the elementary and middle school levels has increased over the last 30 years, but has stagnated in high school. In its 2018 report “Catalyzing Change in High School Mathematics,” The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics has issued a call to action to drastically change the way math is taught so that students can learn more easily. Read the article featured in District Administration.

Study Explores What Makes Strong Science Teachers

A new study shows that eighth-grade science teachers without an educational background in science are less likely to practice inquiry-oriented science instruction, a pedagogical approach that develops students’ understanding of scientific concepts and engages students in hands-on science projects. This research offers new evidence for why U.S. middle-grades students may lag behind their global peers in scientific literacy. Inquiry-oriented science instruction has been heralded by the National Research Council and other experts in science education as best practice for teaching students 21st-century scientific knowledge and skills. Read the article featured on Phys.org.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

What Does 3-Dimensional Space Look Like

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2018-06-28

When transitioning my classroom instruction to three dimensional learning, I decided to start with one or two areas in each unit or lesson set where I felt the most need. I was already purposeful in selecting activities that I carefully sequenced to support student learning of concepts and big ideas, but I expected students to make connections using crosscutting concepts without explicit instruction. In addition, I was not using phenomena as a vehicle for explanation, but assumed that once students learned the concepts, they would be able to apply them to explain the everyday phenomena that they encountered. I also knew that the way in which I used models in my classroom needed to be rethought. For that, there was no better place to start than my space science lessons.

I felt very comfortable with the activities I used in my space science instruction. Most of them were models that I had been using in my classroom and with girls at Girl Scout events for many years. Traditionally, teachers have used models in space science instruction to make the concepts and processes that are difficult more accessible to students. In my space science lessons, I used a variety of models – physical models, drawings, diagrams, and even kinesthetic models to illustrate science ideas for students. There is nothing wrong with these types of models and they are an important resource for classroom use; however, I was using them very narrowly thus missing important components for sense making. I was not effective at making sure that students were using the models to develop their ideas or make connections between their ideas and the phenomena. I realized that I needed to take a step back and analyze how students were using the practice of developing and using models in my classroom. How were they using models to connect their ideas to phenomenon and how was I going to better facilitate that?

I started with the lessons around the phenomenon of daily changes of length and direction of shadows created by objects and the sunlight. After eliciting student ideas about how their shadows changed or stayed the same at different times of day on the playground, as a class, we developed a method for testing these ideas. In partners, students used a golf tee on a large sheet of paper and traced shadows of the tee every hour during the school day. The next day, the partners discussed the patterns they observed in their shadow data. Then they did a gallery walk to view other groups’ shadow data to decide if there were similar patterns. As a class, we discussed that two patterns were observed. The shadows shortened until midday and then lengthened until we stopped collecting data. In addition, the shadows moved from west to east on their papers in a northerly direction (Fig. 1). I asked them if there were other ways we could represent the daily shadow lengths and directions to show the patterns. They determined that we could graph the lengths and the angles of the shadows. After doing that and writing about our observations, I asked them if this occurs every day and if so, why does this occurs? So we embarked on a quest for cause and effect.

I gave them the task of recreating their shadow data in the classroom with a flashlight and golf tee. They discovered that there was a pattern of light movement that occurs that coincides with the pattern of shadows. My questioning led them to a cause and effect relationship between the position of the light and the resulting shadow length and direction. Does that mean that the sun changes position in the sky during the day? So we set out to find out. This was done by observation outside and the use of Stellarium, a computer planetarium software, and led to the question of why the sun changes position in the sky in a pattern – another cause and effect relationship. Most of my students can tell you at this point that it is because the Earth is rotating; however, if I question them further for a more detailed explanation, they falter. At this point, I bring in the models – flashlights and inflatable globes, computer simulations, and one of my favorites, Kinesthetic Astronomy.

Kinesthetic Astronomy can be used as a model of Earth’s movements. In this model, students are the Earth and stand in a circle around a student Sun. In their left hand, they hold a stick with the letter E representing east and in their right hand they hold a stick with the letter W for west. Their arms are outstretched representing the horizon. With their arms outstretched, they are asked to rotate in a counterclockwise direction (Fig.2). If they look down their arm when their arms are pointing in the direction of the sun, they can see the sun along their arm or horizon. This is sunset or sunrise, depending on which arm is pointing in the direction of the sun. If the front of their body is facing the sun, it is midday and if the back of their body is facing the sun, it is midnight. We use the front of their body as their position on Earth. As they rotate during the day, I ask them to notice the change in the position of the sun – lower in the sky at sunrise and sunset, getting increasingly higher from sunrise to midday and then lower from midday to sunset. In years prior, I assumed this part was evident in the model and they could see this relationship. However, this time, in my effort to make sure students made connections to their ideas and the phenomenon, I asked them to turn to a partner and discuss how this related to the changing length and direction of shadows. As I walked around, it became clear to me in listening to their conversations, that students did not see the changing angle of the sun in their “Earth” rotation in this model. How could I help them with this?

The next day, I brought out a lamp without a lamp shade. We did the kinesthetic model again with the lamp as the sun instead of a student. This made the difference for some students and they  could see the changing position of the sun (lamplight) and relate it to their observations outside or on Stellarium, but many were still not making those connections. After much thought, I came up with an idea that I hoped would help. I attached a protractor to a meter stick (Fig. 3).

could see the changing position of the sun (lamplight) and relate it to their observations outside or on Stellarium, but many were still not making those connections. After much thought, I came up with an idea that I hoped would help. I attached a protractor to a meter stick (Fig. 3).

The meter stick became the horizon and I attached the E and W to each end. There was a piece of string or yarn connected to the protractor. In partners, they used this model to note the changing angle of the sun during rotation. One person was the sun and held the end of the string. The other person was Earth and rotated from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). The yarn then showed the changing angle of the sun which they could connect to their observations.

protractor. In partners, they used this model to note the changing angle of the sun during rotation. One person was the sun and held the end of the string. The other person was Earth and rotated from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). The yarn then showed the changing angle of the sun which they could connect to their observations.

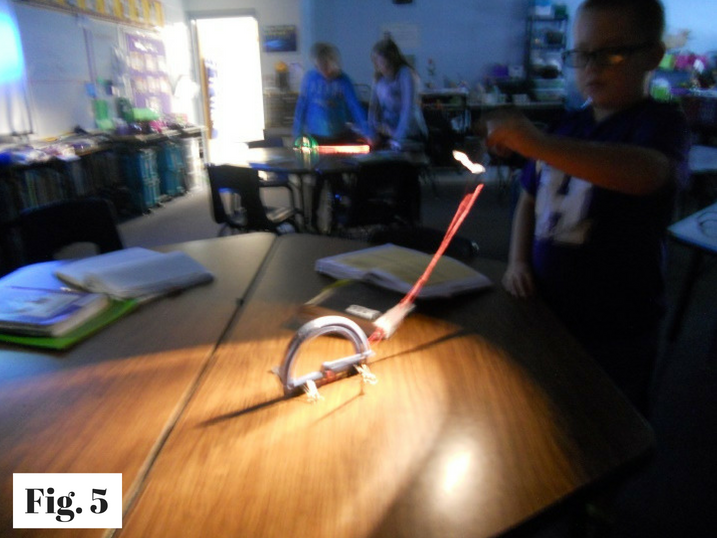

I then gave them a protractor attached to binder clips (as a stand) and a flashlight and asked them to create a model to show the changing light on a table or the floor connecting it to the meter stick model (Fig. 5). We discussed as a class how we modified the model we were using to better explain daily shadow changes. This set the stage for revision of models as an explanation tool for phenomenon for the rest of the year.

Throughout this instruction when using models, I also made sure we were explicit in identifying the features that the models were highlighting, and also what features were either not accurate or left out of the models. In other words, what are a model’s limitations?

These changes and attention to how students were using the practices and crosscutting concepts vastly improved student learning in this set of lessons. This process of reflection about three dimensional learning is ongoing in all of my lessons and units. It is impossible to change everything at once. We need to be patient with ourselves and continually reflect and make changes in our practice to strengthen students’ ability to explain the phenomena around them. It will take time, but the change will be worth the effort.

These changes and attention to how students were using the practices and crosscutting concepts vastly improved student learning in this set of lessons. This process of reflection about three dimensional learning is ongoing in all of my lessons and units. It is impossible to change everything at once. We need to be patient with ourselves and continually reflect and make changes in our practice to strengthen students’ ability to explain the phenomena around them. It will take time, but the change will be worth the effort.

Betsy O’Day is an elementary science specialist at Hallsville Intermediate in Hallsville, Missouri.

This article was featured in the June issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2018 STEM Forum & Expo

Dive into Three-Dimensional Instruction Workshop

2018 Area Conferences

2019 National Conference

Follow NSTA

When transitioning my classroom instruction to three dimensional learning, I decided to start with one or two areas in each unit or lesson set where I felt the most need. I was already purposeful in selecting activities that I carefully sequenced to support student learning of concepts and big ideas, but I expected students to make connections using crosscutting concepts without explicit instruction.