feature

Integrating Critical Pedagogy of Place

How kindergarten students explored the needs of living things in their school's urban environment

Science and Children—March/April 2023 (Volume 60, Issue 4)

By Alayla Ende, Alexandra Schindel, Jennifer Tripp, Christine Wang, and Tanya Christ

Young people are increasingly becoming the face of the climate movement as they implore adults and politicians to take immediate action on the climate crisis. Teachers are on the front lines of educating young people about our environment. Yet, we are often caught between the tensions of state mandated curricula and building social responsibility. Young people need educators who can help them navigate the complexity of socioscientific issues in ways that foster hope and care while mitigating fear and anxiety. One way we do this is through engaging students in environmental action. Critical Pedagogy of Place (CPP) provides a pedagogical framework that emphasizes environmental action by grounding science learning and action in students’ lives and the natural world around them. CPP combines (1) place-based education with a focus on learning content through studying and valuing specific places and concerns, and (2) critical pedagogy, which emphasizes critical awareness and taking action on injustices (Gruenewald 2003; Schindel Dimick 2016).

CPP allows children to use their prior knowledge and experiences to support their science learning and take meaningful action within their community (Birmingham and Calabrese Barton 2014; Schindel Dimick 2016; Senechal 2014). Research shows that when students in underserved communities engage in locally and culturally relevant science their learning outcomes improve and they identify as participants in science (Bang and Marin 2015; Bang, Medin, Washinawatok, and Chapman 2010; Kincheloe et al. 2006; Lim and Calabrese Barton 2006).

Place-based learning has too often focused on the natural world as places “out there” to be preserved rather than places all around us (Finney 2014). Further, place-based learning too often excludes urban places, thus ignoring the ways these complex sites reflect regional biodiversity and complicated social and political histories within the United States. Our goal for this project was to engage young learners in thinking about their own urban place within the context of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Compelled by these concerns, we drew upon CPP to develop curricula that teaches young urban learners about science and living well with the natural world in ways that are culturally and developmentally appropriate. Further, we developed the curricula to align with NGSS within an early childhood setting.

School and Community Context

The CPP curricular unit we share here was developed in 2019 for a K–8 urban charter school in a highly segregated and predominantly Black neighborhood in a Northeastern city known for its rich African American heritage but also known for a deep history of segregation and inequality. The school is in a heavily populated neighborhood with an under-utilized, enclosed courtyard containing grass and one bush but no other plants. There are three full-day kindergarten classrooms in the school with a total of 59 kindergarten students aged 4–5. The majority (81%) of the kindergarten students were Black or African American and 94% of the students at the school were classified as economically disadvantaged. The school allotted 30 minutes for science or social studies at the very end of each day.

Designing the Unit

A team of university researchers and the school’s science curriculum specialist developed the unit and provided professional development to the three kindergarten teachers to implement it. The unit was the first science experience of the year for kindergarten students and addressed the following NGSS performance expectations: K-LS1-1: Use observations to describe patterns of what plants and animals need to survive; and K-ESS3-1: Use a model to represent the needs of different plants and animals and the places they live. We deliberately used place-based content that aligned with the CPP outcomes to lay a foundation for kindergarteners to begin considering how a place and its inhabitants are interconnected.

The unit consisted of 12 lessons across four weeks. Weeks 1 and 2 focused on the scientific practice of developing and using models as well as building background knowledge about plant and animal needs (K-LS1-1). Weeks 3 and 4 aligned the NGSS performance expectations with CPP and focused on the survival needs of three local organisms: monarch butterflies, blue jays, and milkweed plants. In these lessons, students explored their school courtyard and continued developing scientific models about how plants and animals are interconnected and inhabit local places, such as the school courtyard (K-ESS3-1).

Week 1: Scientists Use Models!

To begin this unit, we started by having the students wonder about the phenomenon of a bee pollinating a flower. In Lesson 1, the students’ asked questions about a YouTube video (see Online Resources), and the teacher recorded these questions. Then, teachers did an interactive read-aloud of On Meadowview Street by Henry Cole (2007). We chose this book because the main character creates a green space in her local, urban area. As she adds more elements to the meadow (pond, tree, flowers) more animals come and make their homes there. Urban landscapes are home to many diverse species, and we wanted the students to see how biodiversity of plant life invites greater biodiversity of other living things.

In Lesson 2, students were introduced to developing and using models. Students were given a model of a meadow and teachers used the word model to describe the materials (see Supplemental Resources). The teachers led a whole-class discussion where students identified the living things represented in this model. The teachers then focused students’ attention on the maple tree and the wren in the model (both organisms found in the On Meadowview Street book) and led a discussion about what the maple tree and the wren needed to survive. The teachers referred back to pp. 9–10 of the book when Emily added a pond to her meadow and asked students questions to guide their thinking about plant and animal needs and the places they live, such as, “What kinds of new creatures do you think will come to the preserve now that there is a pond with water? What is your evidence? Why do you think there weren’t any turtles before?” Student responses listed animals such as fish, frogs, and ducks as animals that might come to the preserve now that there is a pond. Some students were able to describe the cause and effect that having a pond allowed turtles to live there.

To wrap up the first week, students used the lens of the systems and system models crosscutting concept to continue their use of models. In Lesson 3, students were given a model of a meadow that contained a maple tree, grass, and a pond (see Supplemental Resources). Students were given eight pictures of organisms (wren, butterfly, turtle, cattail, flower, frog, and snake) and completed a cut-and-paste activity. For each organism, the teacher asked, “Where on our model do you think the __ should live? Why?” Students were successful in matching each animal with a possible home. Lesson 3 concluded when students came to a consensus and then each student glued the organism on their model. This activity may be modified for students with disabilities by rephrasing the question such as “What does the ___ eat? Do you see that on our model?” Additionally, the teacher may have additional adults, such as special education teachers or teacher’s aides, work with students who need support in a small group. To differentiate for students who are above grade level, the teacher may allow students to draw additional organisms that are not included in the activity to their model. The teacher should ask these students, “How do you know that animal could survive in the meadow?”

Week 2: Scientists Obtain Information!

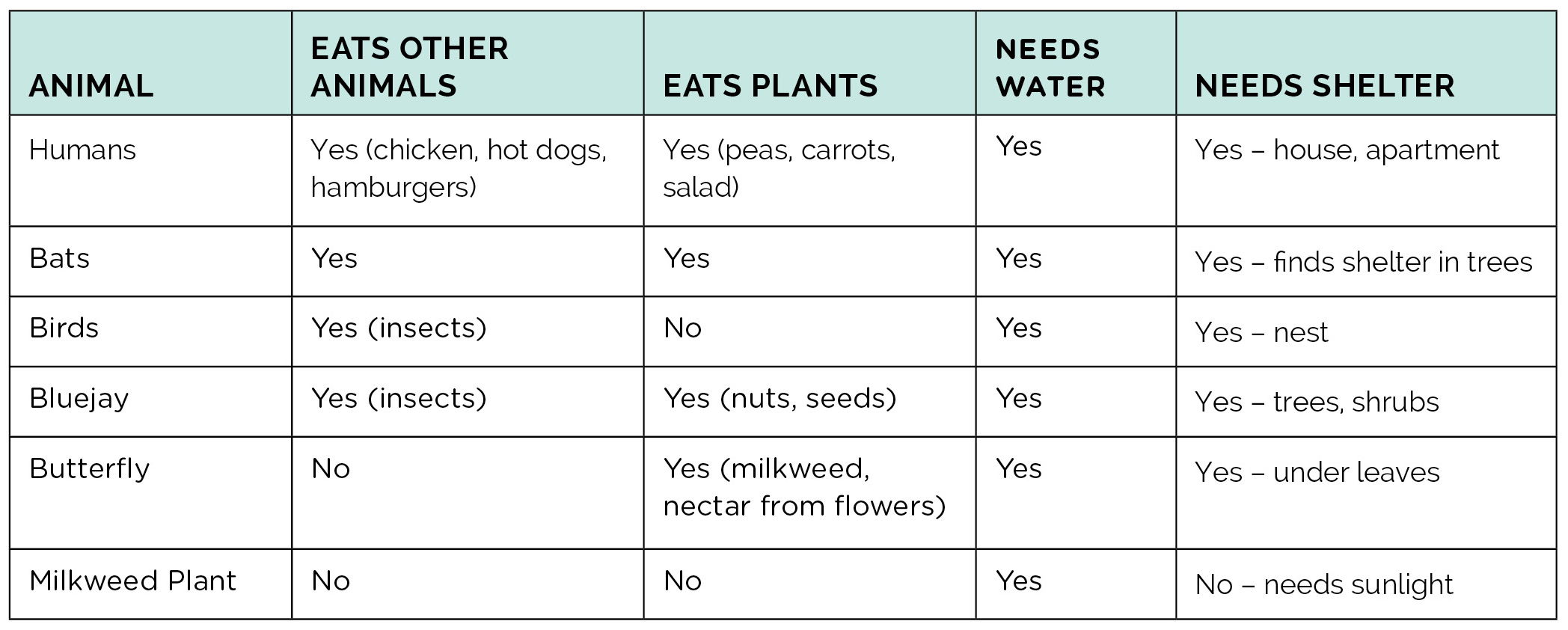

The second week of lessons focused on building background knowledge about what different plants and animals need to survive. Students engaged in a discussion about where their food comes and how humans eat both plants and animals to survive. Teachers created a large anchor chart on chart paper to record the students’ observations and to allow students to recognize patterns across multiple organisms. A completed anchor chart is shown in Table 1. The anchor chart was created in Weeks 2–4 and was referenced across the rest of the unit. In Lesson 4, the teacher added humans to the anchor chart.

Example of completed anchor chart.

In Lesson 5, the students engaged in the obtaining information SEP by gathering facts from the book Stellaluna by Janell Cannon (1993) and added bats to the anchor chart. Following that, in Lesson 6, students obtained information from a YouTube video about baby birds being fed and added birds to the anchor chart (see Online Resources). The students were given copies of the anchor chart and added pictures to the food and shelter row for birds. The week ended with students discussing the patterns they observed about the needs of humans, bats, and birds. Some patterns students noticed were that bats, birds, and humans all needed water and shelter. The teachers had students share examples of how they meet their needs of water and shelter.

Week 3: Scientists Look for Evidence!

For our development of place-based phenomenon, we partnered with a local expert to develop two videos that focused on the interconnection of local plant species, blue jays, and monarch butterflies (see Supplemental Resources). In Lesson 7, students obtained information from the videos to learn about what monarch butterflies and blue jays need to survive. In the next activity, students pretended to be monarch butterflies or blue jays looking for the plants they need to survive by collecting pictures of the plants the teacher had placed around the classroom. Students worked with partners and had to explain to their partner why they chose certain pictures using evidence from the videos. Then, teachers led a discussion and added both blue jays and monarch butterflies to the anchor chart.

In Lesson 8, teachers reviewed with students what monarchs and blue jays need to survive and asked students to make a claim (constructing explanations) about whether or not monarchs and blue jays could survive at our school. Then, teachers told students that we needed evidence to back up their claims. Teachers directed students to explore the school courtyard and helped students use iPads to take pictures. Students were directed to take pictures of any living things, any birds or butterflies, and anything that monarch butterflies or blue jays need to survive (food or shelter). Students enjoyed the opportunity to explore the area around the school and took pictures of trees, grass, bushes, and flower planters.

In Lesson 9, students re-visited the pictures of the school courtyard and drew initial models of what the courtyard looked like. Teachers led a discussion where students used their pictures and models as evidence for whether monarchs and blue jays could survive in the school courtyard or not. Students brainstormed solutions about how we could change our school courtyard to make it a place where monarch butterflies or blue jays could survive. Teachers let the students know that they were going to be able to plant a garden in the school courtyard to meet the needs of butterflies and blue jays.

Week 4: Scientists Plant Gardens!

In Lesson 10, students explored milkweed plant pods. Students opened them up and discovered that there were seeds inside. Remind students to not put anything in their mouths in the science classroom, and make sure hands are washed after handling plants. Teachers added the needs of the milkweed plants to the anchor chart and led a whole-class discussion about what the class needed to do to make sure the plants survive and how that would help the blue jays and monarch butterflies meet their needs.

The assessments for this unit took place during Lesson 11. In this lesson students went outside and planted the milkweed seeds along with other local plants described in the monarch and blue jay videos. Then, students returned to the classroom and drew a final model of the courtyard with the addition of the garden. To differentiate this final assessment, teachers may provide scaffolding of the model. For example, the teacher may have a sheet with the courtyard and the plants already on the model and students just add the animal organisms. Teachers asked each student individually about their model and how it would help the monarch butterflies and blue jays survive. This short interview was used as a summative assessment for this unit and a rubric for this interview is shared in the Supplemental Resources. Finally, in Lesson 12, students held a gallery walk for other students and adults in the school. Students posted their before and after models of the courtyard and were encouraged to explain what they planted and why they planted it.

An additional life science kindergarten PE focuses on how organisms—including humans—can change their environment to meet their needs. Therefore, the courtyard planting could also be used as a scientific phenomenon for the next science learning segment. The lesson plans for all 12 lessons of this unit are included in the Supplemental Resources.

Conclusion

This learning experience was successful in using CPP to help level the playing field for young, urban students as they made sense of phenomena and took action to increase the biodiversity of their school courtyard. All three kindergarten teachers described how the students may have limited opportunities to be outside when at home due to a variety of reasons. This project helped teachers and students to realize that urban environments are home to many plants and animals. Teachers also noted how this project could help students understand that humans can change the environment to better meet the needs of living things. One teacher explained:

I think conservation of our environment is very important, and if we want students to grow up to be conscious citizens, they have to know what’s going on around them. They have to know how to be able to take care of what’s around them, and if they want to see more of the beautiful things that we see in nature, how to make that happen, and I think that’s something that’ll be long lasting for them.

This project also showed how urban environments can be used as phenomena for NGSS instruction. Implementing these lessons shows how NGSS and CPP can be leveraged to remove learning barriers, promote equity in early childhood science education, and promote relationships with the natural world.

Download the lesson plans, assessment, and rubric at https://bit.ly/3kp4H9V.

Online Resources

Bees Pollinating Flowers: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CdoBCEEpz4

Feeding Baby Birds: www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8ifycZhuTI&t=3s

Alayla Ende (alaylahe@buffalo.edu) is a director of curriculum and instruction at King Center Charter School in Buffalo, NY. Alexandra Schindel is a science education professor at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Jennifer Tripp is a science educator for Buffalo Public Schools and the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Christine Wang is an early childhood professor at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Tanya Christ is a literacy professor at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan.

NGSS Pedagogy Science and Engineering Practices Teaching Strategies Elementary