feature

It Can Happen Here!

A preK class investigates wildfires.

One would expect a wildfire exploration in a region prone to wildfires to begin close to home, not Australia, but that is where ours started. I teach preK in a constructivist school in an area prone to wildfires, earthquakes, winds, and floods. One of my students went back to visit relatives in Australia during the winter of the 2019–2020 school year, immediately before the initial COVID-19 quarantine. We emailed the student regularly and heard about the intense heat where he was visiting. We looked up Australia in the news and saw images of the wildfires. After a little work comparing Australia and our area, one of the students said, “This could happen here! We HAVE to do something!”

Engaging With Play

My students were mostly four and five years old and very emerging readers. The first step was to uncover what they already knew about fires in general. With this age especially, physically manipulating objects helps their sensemaking much better than other methods.

Knowing that many of my students were familiar with camping, I started with having them make pretend paper campfires (Figure 1). This allowed them to review facts about fires needing oxygen, ignition source, and fuels. Remembering that wet firewood doesn’t burn helped them develop the opposite idea: the drier the fuels, the more easily they will burn. A favorite imaginative play ignition source came out of our music center: a yellow rhythm stick to represent lightning! Fires were often taken to the block area or to the home center to reenact camping stories and the rescue of Smokey Bear.

Students made paper campfires as they began discussing fire.

We discussed common causes of wildfires and ways to prevent them. Several students remembered earlier in the year when we had done an investigation of our state and had the opportunity to examine tumbleweeds up-close. Students connected the memory of the tumbleweeds, quite common in the winter months, with dry fuels waiting to be lit.

At this point many of the students interviewed their own families to find out their own experiences of wildfires. We heard stories of fences burning, watching water being dropped from a back porch, favorite campsites reduced to ashes, and seeing the surrounding pink clouds from dropped flame retardant.

Over the next week, the students created a huge list of questions, both in our class meetings and during exploration time. Each question was added to the board, reviewed by the class, and then edited or consolidated with another question to create the final list (Figure 2).

Questions about fighting fires.

- How do firefighters find animals to rescue?

- What kinds of tools and machines do you use?

- Do you always use the same machines?

- What do you do if there is not a high enough ladder?

- How does the fire sucker work (the tube used to suck up water from ponds)?

- How do you know where the fires are in the forest?

- What happens if there isn’t a road to get to the fire?

- Where do the firefighters take the animals?

- How do they get the animals to the wildlife doctors?

- Do paramedics take care of hurt animals too?

- How do fire fighters fix trees so they don’t fall when they are burning and land on trucks?

- What keeps firefighters safe in the fire?

Engaging the Community

My students were fortunate to have members of the school who were professional firefighters. Fire Captain Armstrong visited for about 30 minutes and answered many technical questions about putting out fires. Fire Chief Alameda visited for over an hour and not only answered our questions but helped us think in terms of prevention. Additionally, he showed us some of the common fuels for wildfires, including invasive weeds such as cheatgrass and Russian thistle; if we removed these fuels when we saw them, we could help prevent wildfire spread.

We looked at cheatgrass and remembered seeing it everywhere! We worked on key words and used trusted sites to investigate cheatgrass and Russian thistle online, deciding that such sites as PBS, National Geographic, and our local agriculture extension would be safe and reliable sources of information. We discovered that cheatgrass crowds out native plants by taking available water, dries out early in the spring, and, once ignited, can spread fire easily. We also looked at prickly tumbleweeds, remembering them from last fall, and noticed how much seed was shed each time we bumped it! We found out that these have long taproots that take a lot of water away from other plants and are always very flammable. The students immediately began a campaign with their parents, hunting and removing cheatgrass and tumbleweeds.

But wildfires also burn trees. To help my students better understand that, we invited educators from a local organization, Living With Fire, to come and talk to the class. They helped us think in terms of a community instead of just our individual homes, and how fires in one house will affect other houses. They showed visuals explaining the size range of embers, from a grain of rice to a basketball, with a common distance travelled of a mile!

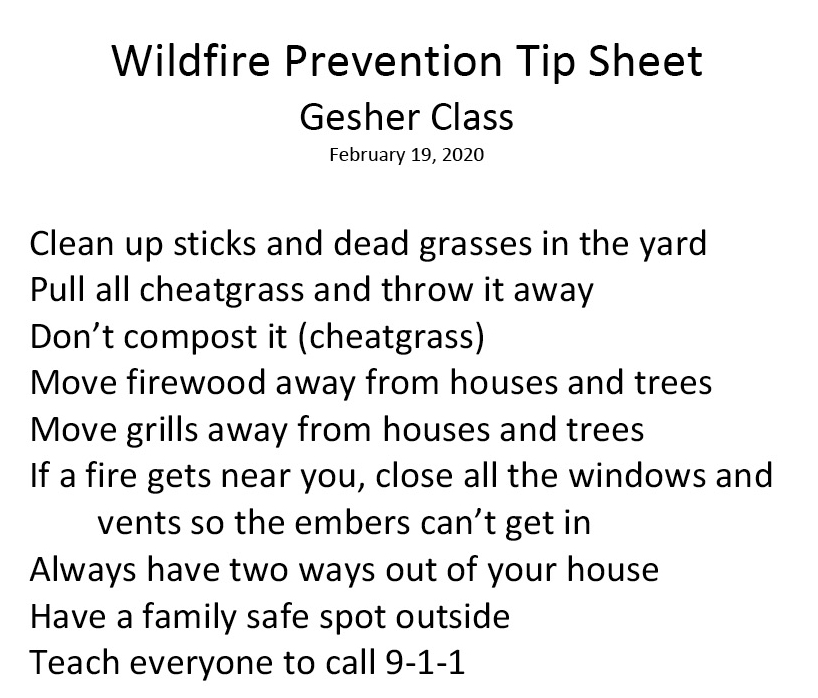

The educators from Living With Fire also brought a teaching prop, The Ember House (Figure 3), for student to discover fire risks by tossing orange-fringed beanbags at the house and causing pretend fires. Through the process, my students learned several facts and plans for sharing those facts began to form. They decided they needed to educate their parents about fire safety and created a tip sheet for families (Figure 4).

Ember house demonstration.

Wildfire tip sheet.

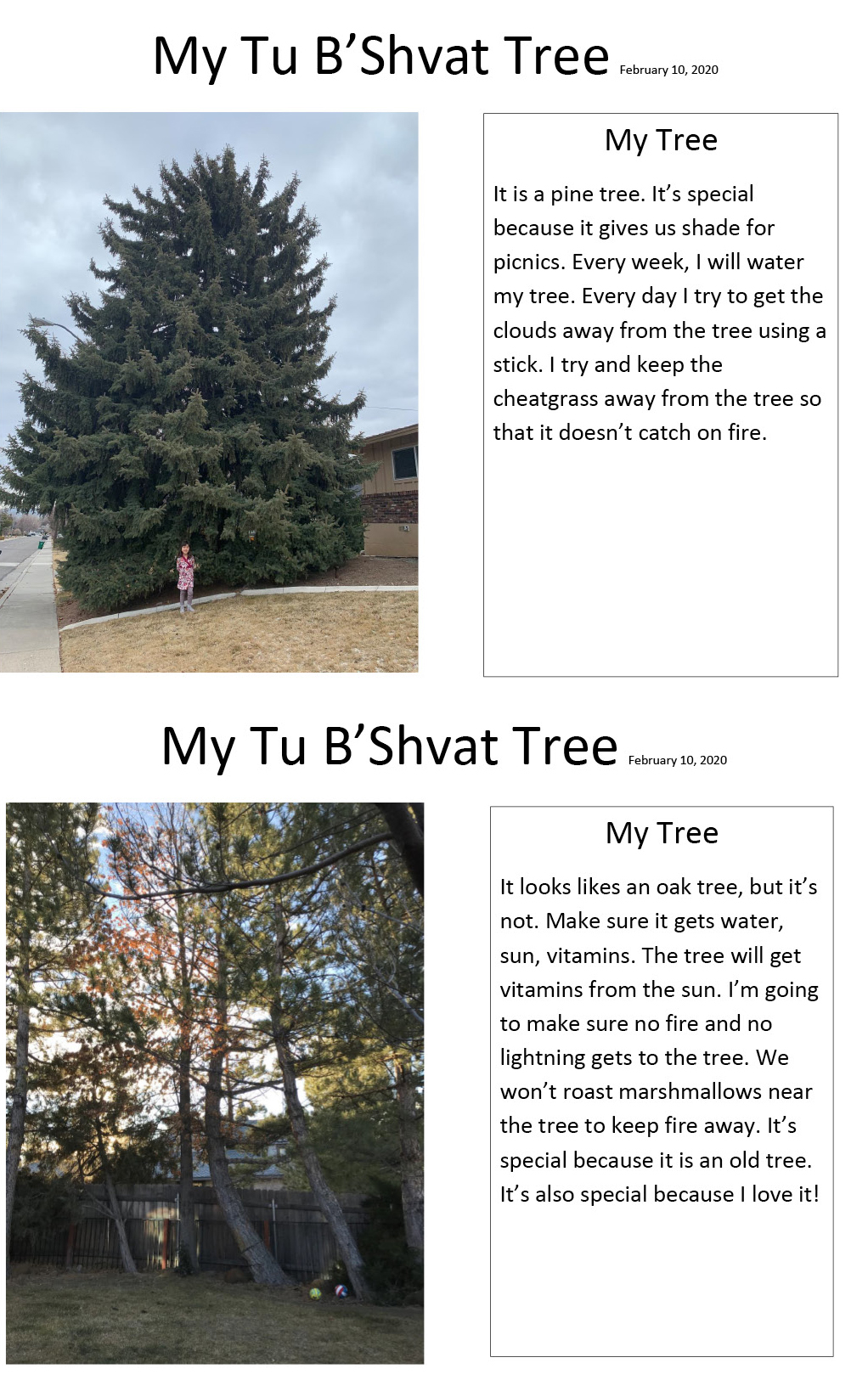

That was a good start, but my students wanted to do more. During the school Tu B’Shvat celebration (“The Birthday of the Trees”), students had dictated about their favorite trees where they lived (Figure 5). After sharing these in class, it became evident the students were worried about trees and fire.

Tu B’Shvat.

Modeling and Sharing

My students wondered, “What could they do?” They decided they would focus on defensible space and include trees. Their reasoning was that trees near houses are already flammable. Families need to consider fire safety when planting new trees and work to keep the current trees safe through watering, disease prevention, and keeping flammable materials away from both trees and houses.

After a class discussion of possibilities of how they could explain it to their families, they decided to model defensible space. They would create trees instead of bushes or grass, for several reasons. The first is that the bushes and grasses, while flammable, did not “take up as much space as trees.” The second reason was the embers flying in the air were more likely to catch in the crown of a tree and be far more dramatic.

But what to use for trees? Originally, the students used recycled tubes from our art center. But after those ran out, they had to create their own, which made for a multilevel engineering project. How to make a stand-up tree? How thick a cylinder did they need to roll for the tree to be stable? How would they roll it so the trees could stand flat? Similar questions came up and were explored with creating the paper houses as well.

What to use for embers? Live embers were ruled out immediately, with a suggestion to talk with your families and share at school. A boy with an older brother came back with a pea shooter idea, using a straw and a wadded-up piece of paper inside. This idea was immediately approved, with several community created safety guidelines in place, including shooting the ember papers all in the same direction, and down low. Additionally, to forestall possible concerns about inhalation, the teacher modified the paper wads to a cotton swab with one end cut off. Wrapped in a strip of red tissue paper, it made a wonderful ember shooter. (Modification would be flicking a red pompom off of a block, eliminating the need to blow air; directions for both are shared; see Supplemental Resources).

With the safety guidelines, trees, ember shooters, and houses made of paper, the students were ready to show their families that trees too close to a structure, or too close together, dramatically increase the potential for disaster during wildfires.

The students took the materials home and showed their families. While no families reported cutting down any trees, there were reports of families were looking to change and maintain the vegetation near their houses, as well as removing invasive weeds and other flammable materials (such as woodpiles).

This phase of the project ended by making go bags, where each student created a list of what to include in their bags. One student even drew two ways out of the neighborhood on the outside, while another drew two ways out of the house and the family meeting spot. Unfortunately, several of these bags were used the following year as several local neighborhoods evacuated due to fires.

Epilogue

Shortly after the students drew the go-bags, the school closed in March 2020, due to the initial COVID-19 quarantine. However, when our school reopened in June 2020, the students involved in this project immediately began educating the younger students at the school, because, as they all said “prevention starts before the fire starts.” and “This CAN happen here!”

As this exploration was ended for us when our school year ended in March, I think it’s important to mention both our future plans were and the families’ reactions to our exploration.

Before we left, the students were very interested to learn if there were native grasses and wildflowers that could replace cheatgrass; we had a representative from our local agriculture extension office scheduled to visit the class at the end of March. I found local wildflower seeds in my own seed stash at home and added them and sunflower seeds to an activity bag drop in April. Later in the year, the students sent in pictures of what they had grown.

I was concerned that focusing on wildfires would stress my students and their families, but the opposite happened, based on conversations with students and families. Instead of worrying that fires might burn their own homes, students told their families how to prepare so fires wouldn’t be as likely to happen. Such actions continued even as the wildfire activity increased during the fall; all of the families involved let me know that the students were informing the rest of the family about their personal risk assessment as well as prevention measures. With one fire in town in the fall, I heard that go bags were packed, and many students were reassuring other family members.

When school restarted in June 2020, I saw similar activity from students continuing in the summer session; they worked at teaching the younger students “so everyone knows!”

Natural disasters such as wildfires are scary, partially because they are unpredictable and can be devastating. However, in my class, teaching students about the mechanics and things they can do to mitigate their risk significantly decreased the fear!

Supplemental Resources

Find additional resources and a description of the embers activity at https://bit.ly/3mM6kjg.

Online Resources

FEMA for Kids https://community.fema.gov/ProtectiveActions/s/article/Wildfire

Living with Fire www.livingwithfire.com/

National Fire Protection Association www.nfpa.org

Smokey Bear https://smokeybear.com

Anne Lowry (alowrynews1@yahoo.com) is a preKindergarten teacher at Aleph Academy in Reno, Nevada.

Instructional Materials Phenomena Physical Science Early Childhood