A Call to #retireELL in Science Education

By María González-Howard, Enrique Suárez, and Scott Grapin

Posted on 2021-08-17

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).

There is no shortage of terms when referring to students learning English as an additional language. Schools, districts, and policy documents often refer to these students as English language learners (ELLs), while educational researchers and teachers are increasingly adopting terms such as multilingual learner or emergent bilingual. This assortment of terms may leave those who work in science education wondering,

“What do the different terms mean?”

“Which term should I use?”

“Why does it matter?”

On May 20, 2021, we organized and moderated the #retireELL Twitter chat in collaboration with the Journal of Research in Science Teaching. Building on two commentaries we published in the journal (González-Howard and Suárez 2021; Grapin 2021), the chat’s purpose was to initiate an interdisciplinary dialogue among science and language educators about the need to adopt terminology and pedagogies in the science classroom that reflect asset-oriented views of students learning English as an additional language. The chat brought together participants representing research, policy, and practice across the science and language education Twitter communities, reaching more than 10,000 users and generating almost 45,000 impressions on Twitter (including likes, mentions, and retweets associated with the #retireELL hashtag).

In this blog post, we synthesize key takeaways from the chat and their implications for those working in science education. The synthesis is organized around three questions posed to participants during the hour-long chat about the labels we assign students and their consequences. We also feature representative tweets from participants. Ultimately, our goal is to extend the conversation beyond the Twitterverse into classrooms, teacher workrooms, professional learning communities, and any other venues where educators are committed to advancing equity and justice in science education for multilingual learners.

1. What term(s) have you used for students learning English as an additional language?

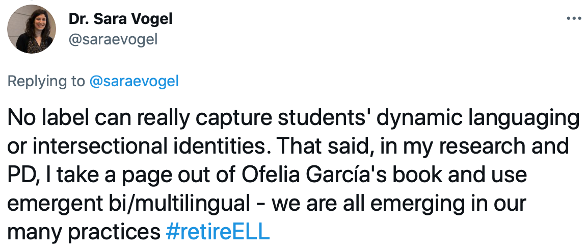

Participants noted a shift in their terminology over time. They initially described using limited English proficient (introduced as part of No Child Left Behind of 2001) or ELL because these terms were commonly used in schools when participants were students themselves or when they were teaching in K–12 classrooms. However, participants recounted how they came to view these terms as insufficient for capturing their own experiences and the experiences of their students. To challenge the privileging of English and to recognize the rich resources students bring to school, participants described a recent shift toward more asset-oriented terms, such as emergent bilingual and multilingual learner. While the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 still uses English learner (an abbreviated version of ELL), recent policy initiatives, such as the WIDA English Language Development Standards, have moved toward more asset-oriented terminology.

2. In what ways might the term(s) we use for students learning English as an additional language shape their science education experiences?

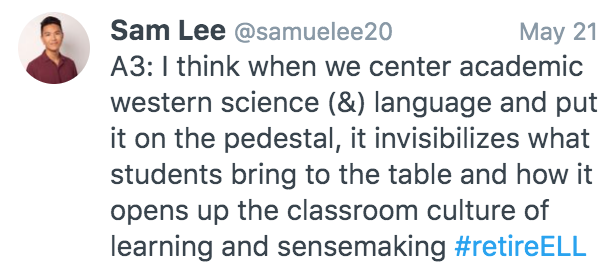

Participants explained how terms such as ELL position spoken and written English as the desired modes of communication in school, which foregrounds English learning as the main activity that multilingual learners and their teachers should focus on. Furthermore, participants described the ways that centering students’ learning experiences around English can lead educators to incorrectly believe that a certain level of English proficiency is prerequisite to rigorous science learning (González-Howard and McNeill 2016). Participants offered examples of how such beliefs manifest in the instructional practices commonly used with multilingual learners, such as pre-teaching vocabulary for a particular topic before students have had the opportunity to engage with a phenomenon (http://stemteachingtools.org/brief/66). Additionally, participants noted that terms such as ELL are deeply unjust in that they mask and divert attention away from the myriad of rich resources that multilingual learners bring to the classroom to make meaning and communicate science ideas with peers.

3. Besides ELL, what other terms or phrases related to multilingual learners in science might we consider rethinking or retiring? Why?

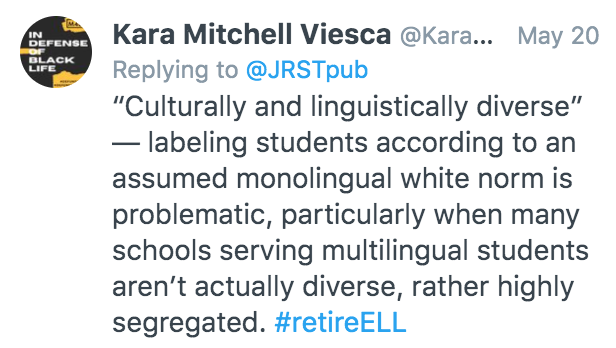

Participants pointed out several other terms and phrases that we should reconsider before using. One participant cautioned against replacing deficit-oriented labels, such as ELL, with seemingly neutral labels, such as “culturally and linguistically diverse learners,” that can serve as code for any student who is not white or monolingual. Beyond labels, participants suggested that we ask ourselves the fundamental (though taken-for-granted!) question: What do we mean by “language” in the science classroom? For example, participants questioned whether common phrases such as “the language of science” send a message that certain ways of using language are inherently more appropriate or scientific than others. This can result in linguistic modes of communication (e.g., talking and writing) being considered more essential than nonlinguistic meaning-making resources (e.g., gestures, symbols, equations) in the science classroom (Grapin 2019; Suárez 2020). Another concern was that “the language of science” could exclude multilingual learners from science learning if these students are judged as not yet having “mastered” the language to participate. One suggested alternative was “language for science,” which emphasizes what students do with all their communicative resources as they engage in science, not whether their language conforms to some predetermined standard.

Where Do We Go From Here?

If there was one overall takeaway from the chat, it was that terminology matters. The terms we use have significant consequences for multilingual learners’ opportunities (or lack of) to learn science. But some terms have become so commonplace in schools that it’s easy to overlook the conceptions and ideologies that underlie them. A call to #retireELL is an important first step, but working toward equity and justice in science education for multilingual learners will require shifting both our terminology and our instructional practices.

We would love to hear from you and to continue this important dialogue! What terms or instructional practices has this blog post prompted you to reconsider? How are you already working toward equity and justice for multilingual learners in science?

You can reach us via Twitter:

María González-Howard: @MGonzalezHoward

Enrique Suárez: @SciEdHenry

Scott Grapin: @GrapinScott

References

González‐Howard, M., and K. L. McNeill. 2016. Learning in a community of practice: Factors impacting English-learning students’ engagement in scientific argumentation. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 53(4): 527–553.

González-Howard, M., and E. Suárez. 2021. Retiring the term English language learners: Moving toward linguistic justice through asset-oriented framing. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 58(5): 749–752.

Grapin, S. E. 2019. Multimodality in the new content standards era: Implications for English learners. TESOL Quarterly 53(1): 30–55.

Grapin, S. E. 2021. Toward asset-oriented and definitionally clear terminology: A comment on González-Howard and Suárez (2021). Journal of Research in Science Teaching 58(5): 753–755.

Suárez, E. 2020. “Estoy explorando science”: Emergent bilingual students problematizing electrical phenomena through translanguaging. Science Education 104(5): 791–826.

Multilingual Learners Equity General Science Literacy Multicultural NGSS Middle School Elementary High School Preschool