Feature

Pivoting During a Pandemic

Transforming In-Person Environmental STEM Field Programs Into Immersive, Online Experiential Learning

Connected Science Learning March-April 2022 (Volume 4, Issue 2)

By Nicole Freidenfelds, Laura Cisneros, Amy Cabaniss, Rebecca Colby, Madeleine Meadows-McDonnell, Todd Campbell, Chester Arnold, Cary Chadwick, David Dickson, David Moss, Jonathan Simmons, Ankit Singh, and John Volin

The integration of STEM and environmental education can be a powerful strategy to engage and motivate diverse learners, as it encourages participation that prioritizes application of scientific disciplinary knowledge and practices to address relevant and current environmental solutions. Benefits of environmental experiential learning are well-documented and include improved academic performance (including in STEM subjects such as math and science), increased self-efficacy, and enhanced emotional wellbeing (Barnett et al. 2011; Bratman et al. 2015; Coyle 2010). Place-based environmental education, in particular, can restore connections between people and spaces by increasing both one’s sense of belonging as well as one’s awareness, emotional care, and investment in environmental socioscientific issues (Herman et al. 2018; Kudryavtsev et al. 2012; Semken and Freeman 2008).

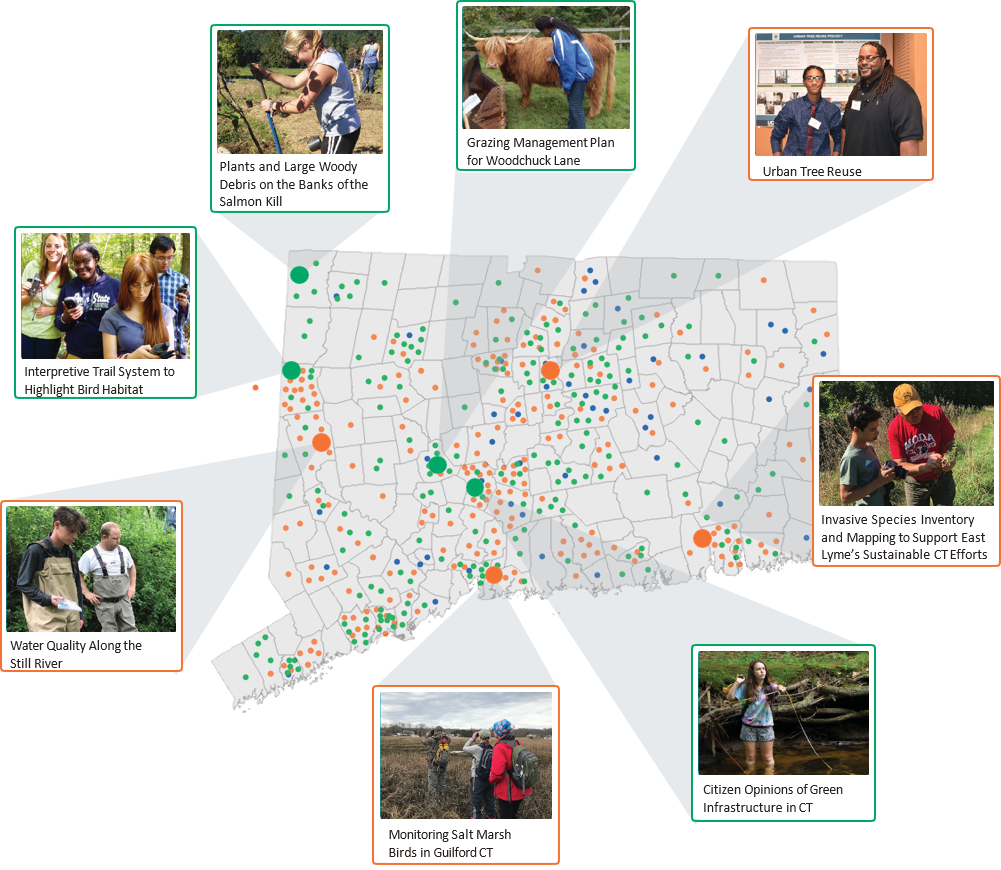

In the face of a global pandemic, environmental educators have grappled with how to effectively translate hands-on, experiential field-based environmental programs into distance learning or online formats (Quay et al. 2020). An online format potentially provides the means to reach wider audiences, thereby fostering more equitable access to informal STEM learning. Yet challenges to replicating place-based, participatory field experiences remotely include: limitations in types of natural areas or outdoor spaces near participants, access to field equipment or resources, inability of instructors to provide individual instruction, and participant screen fatigue. In response to the obstacles faced by the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental education initiatives were adjusted, largely to online distance learning modalities, wherever possible (Quay et al. 2020). Like many other environmental education programs, the University of Connecticut Natural Resources Conservation Academy (UConn NRCA) converted to a remote learning modality in 2020. Since 2012 the UConn NRCA has engaged almost 600 teen and adult participants in natural resources conservation through place-based, experiential outdoor STEM education, and facilitated nearly 260 teen-adult local conservation projects that contributed to environmental solutions throughout Connecticut and nearby states (Figure 1; UConn NRCA 2021).

Traditional Program vs. Remote Program

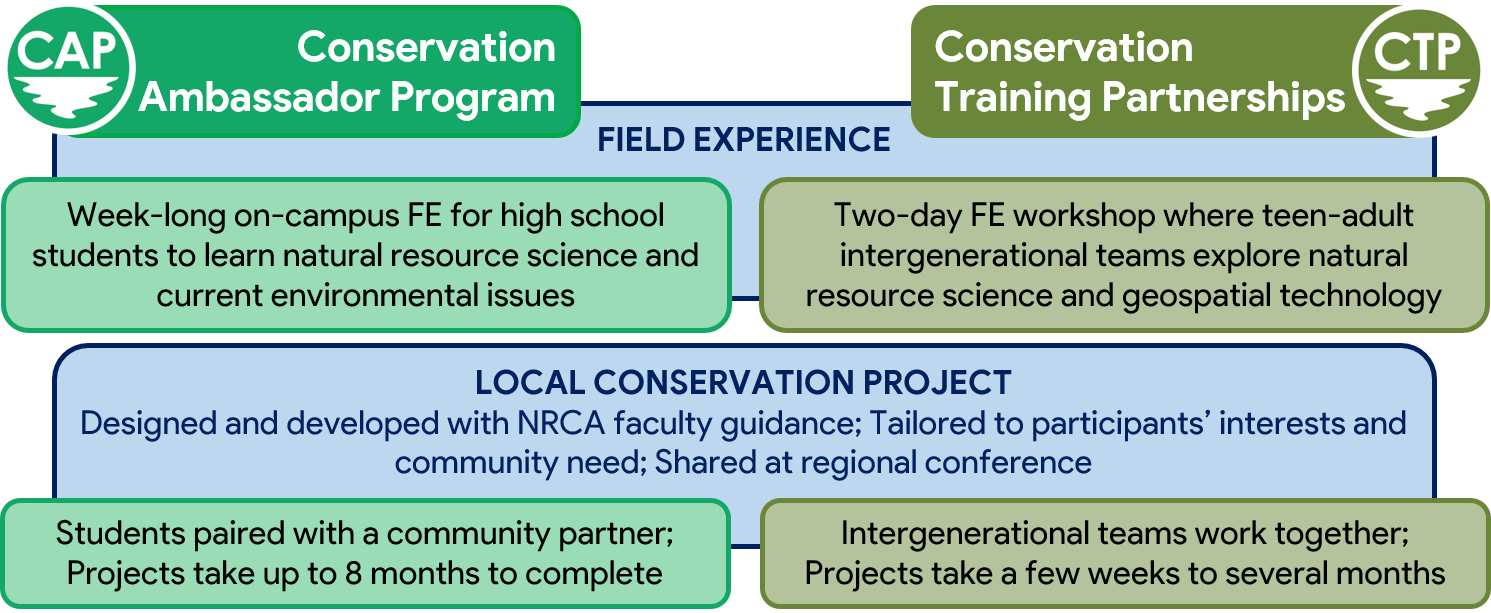

There are two similar, yet distinct, informal STEM education programs within the UConn NRCA that incorporate active engagement through multiple modalities while focusing on natural resources and conservation science and geospatial technology—the Conservation Ambassador Program (CAP) and Conservation Training Partnerships (CTP; Figure 2). Both programs have historically begun with a summer field experience led by an interdepartmental team of university faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students from diverse fields of natural resources and environmental sciences, geospatial science, and science education. Traditionally, CAP has taken place on the University of Connecticut’s main campus in Storrs, Connecticut, annually hosting about 24 high school students from across Connecticut for a weeklong residential field experience. Whereas, the CTP field experience has occurred at various locations throughout the state in the form of two-day workshops for teen-adult intergenerational teams.

During the NRCA field experiences participants learn about, discuss, and investigate natural resource conservation science topics, such as land use change, forest health, water resource protection, and wildlife habitat issues. Through hands-on field activities and exercises, participants explore online mapping technology, data collection, web-based information-sharing platforms, and strategies relevant to local natural resource conservation problems and solutions (Chadwick et al. 2018). The knowledge, skills, and resources gained by participants are applied to local conservation projects completed in the months following the initial field experience, either as teen-adult collaborative teams (CTP) or as a teen mentored by an adult community partner (CAP), often associated with a local conservation organization. Projects typically employ one or more geospatial technologies learned during the field experience, but otherwise vary widely, and include topics such as urban tree inventories, conservation property or trail mapping, invasive species management, water quality monitoring, and educational efforts to foster environmentally responsible behaviors (e.g., educational outreach to boaters to reduce the spread of invasive aquatic plant species; UConn NRCA 2021).

NRCA faculty provide significant post-field experience support through expert advice, technical assistance, and community connection, with access to field equipment and resources to facilitate conservation project success. The CAP and CTP programs culminate in participant project presentations at one of two regional conferences (Connecticut Conference on Natural Resources or Connecticut Land Conservation Conference).

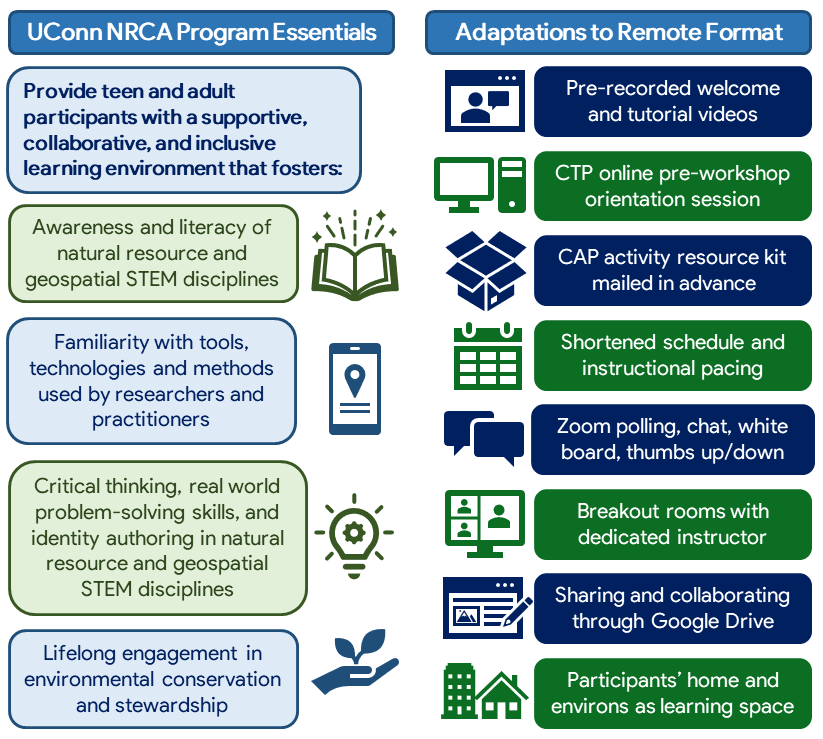

In the summer of 2020, our interdisciplinary team implemented a variety of strategies, modifications, and technological tools to best capture the ‘essentials’ of our traditional in-person NRCA experience while pivoting to an online format (Figure 3). We used multiple forms of synchronous and asynchronous online engagement and limited our software and applications to those that were freely available, most familiar, and most user-friendly, such as Google Drive (a service that allowed organizing, sharing, and simultaneous collaboration on documents between faculty and participants). Our dedicated program web pages provided participants with numerous, easily accessible online resources, including tutorial videos, prerecorded webinars, instructional materials, and reference guides (UConn NRCA 2021). After testing several communication platforms, we chose Zoom Pro (Zoom Video Communications, Inc.) as our meeting platform because of participant familiarity, the ability to enable multiple small breakout rooms for discussions and team-building activities, and the ability to display a large number of user videos simultaneously (i.e., up to 49). Several websites and smartphone applications (e.g., Seek by iNaturalist, Epicollect5, AllTrails, Google Maps, ArcGIS StoryMaps) were also used as educational applications to support participant engagement.

Schedule and Agenda

Both NRCA programs retained their traditional models (CAP: weeklong; CTP: two-day), albeit online and with shorter daily time frames to reduce the risk of screen fatigue and maintain interest and active participation. Program instruction was intentionally paced to deliver one topic at a time (e.g., two-hour, subdivided sessions for CAP; 20-minute sessions for CTP) to maximize student engagement and understanding. To keep participants engaged, activities included the following three approaches:

- whole-group activities to present disciplinary knowledge and information;

- small-group activities in breakout rooms; and

- individual, place-based educational activities at participants’ homes and away from computers (see CAP 2020 Virtual Field Experience Schedule and Conservation Training Partnerships: 2020 Virtual Workshop Agenda in Supplemental Resources).

More camp-like than CTP, CAP students joined faculty and graduate student mentors in early evening activities as well, such as storytelling led by a faculty member tending a campfire. Evening educational events included a bat acoustics activity and student presentations (shared with peers) about different organisms on “biodiversity night.”

Due to the short duration of the CTP field experience workshop, we added a brief pre-field experience orientation session for CTP participants to test internet connectivity and comfort using Zoom, and more importantly, ensure a sense of community and project momentum from the beginning. We held separate orientation sessions for teens and adults and focused on sharing and discussing program communication best practices (Cisneros et al. 2021), which were reinforced throughout the virtual field experience.

Pre-field experience engagement in CAP included online cohort (and parent/guardian) communication, a CAP student guide, welcome video with personalized greetings from all program leaders, CAP Kit, and on-your-own topographic map orientation activity (looking at scale, coordinates, and contours) that eased students into the program. CAP Kits were instituted for the first time due to the programmatic switch to an online platform and emphasis on at-home activities. Mailed to students one week before the start of the program, each package included a

- water test kit,

- soil samples and information packet,

- owl pellet (regurgitated mass of undigested bones, fur, and feathers that can be dissected to identify prey),

- dissection tools and bone identification chart,

- wildlife tracking plate,

- cross section of a tree (“tree cookie”) and tree ring activity sheet,

- field notebook,

- ruler,

- measuring cup,

- USB flash drive,

- topographic map exercise sheet,

- personal water use chart, and

- bat acoustic call identification key.

An NRCA T-shirt, to wear during online sessions, was also included in each CAP Kit.

Instructor-led presentations and hands-on activities provided important background on conservation, natural resources, land stewardship, and geospatial technology, and demonstrated in real time how to use different websites and smartphone applications that could be incorporated into conservation projects (e.g., AllTrails and Seek). Instructors facilitated CAP students’ at-home activities “alongside” participants who used kit materials for water testing, soil characteristics identification, and owl pellet dissection (Figure 4). Participants were shown, step-by-step, how to complete the activity and were intermittently asked questions about what they were experiencing or finding. Similarly, Zoom screen-sharing was used to display instructor smartphone screens to acquaint participants with mapping applications by completing step-by-step exercises together. To increase engagement and community-building, we incorporated the Zoom polling feature, chat box, white board, and visual responses (thumbs up/down) throughout presentations and demonstrations.

We balanced large (whole) group and small-group activities, with approximately equal time spent in each arrangement. Small groups, with one to two instructors present, met in breakout rooms for: (1) icebreaker activities to help participants get to know each other (e.g., environmental trivia, developing team name and mascot), (2) instructor-facilitated discussions on environmental issues, and (3) conservation project development.

Cost

With the NRCA philosophy that finances should not hinder participation, CAP is subsidized through small grants and donations from organizations and individuals to offset the cost of running the program and offer a low student enrollment fee. Further, a sliding fee scale provides cost-reduction opportunities for participants based on household income and number of dependents. Because we did not provide on-campus housing and meals in 2020, the CAP enrollment fee averaged 10% of the traditional program fee. CTP is funded through the National Science Foundation and is free for all teen and adult participants, regardless of program modality.

Safety

In the process of transforming our environmental education efforts to an online learning format, we made use of resources available through UConn’s Minor Protection program to promote a welcoming, safe, and secure experience for our youth and adult participants in an online setting. As with our in-person field experiences, UConn NRCA virtual programs were registered with the university’s Minor Protection Coordinator and all instructors were approved as Authorized Adults upon completion of a criminal background check and Minor Protection online training (UConn Minor Protection 2021). All adult CTP participants (except for parents/guardians) and CAP community partners received approval as Authorized Adults before working on conservation projects with teen participants. Each online session was locked, and breakout rooms were coordinated to prohibit youth-adult one-on-one interactions.

Case Studies

Below we highlight three specific cases where our informal STEM distance learning was particularly successful during the 2020 Natural Resources Conservation Academy programs.

CTP Backyard Biodiversity

This activity began with a brief lesson introducing Epicollect5, a free mobile app installed on participant devices prior to the workshop (iPads were provided to participants with no mobile device). Epicollect5 users can create web-forms that allow community scientists to collect data using a mobile device in the field and upload it to a freely hosted online database. While an instructor screen-shared from a mobile device to demonstrate how to add a specific project (i.e., instructor-created webform to allow collection of backyard biodiversity data) and collect data, participants followed along at home in real time. Once comfortable using the new technology, participants recorded observations of flora and fauna in their backyard or neighborhood for 15 minutes, fostering a connection between individuals and their surrounding spaces. We structured this activity as a teen versus adult friendly competition to boost engagement and replicate the relaxed learning experience of our in-person workshop, and it was exciting to see the number and diversity of observations grow as participants uploaded their data.

After returning to the Zoom platform, the instructor screen-shared the Epicollect5 website and, as a group, we viewed the results in map form (Figure 5). One unique benefit of being remote, as opposed to in-person, was seeing everyone’s observation locations spread throughout Connecticut. The CTP Backyard Biodiversity activity not only got participants outside, connecting with nature in their immediate area, but also equipped them with a new digital tool for field data collection by multiple users. Many CTP teams went on to incorporate the Epicollect5 app in their local conservation projects.

CAP Land Use and Stewardship

Teens participating in the CAP virtual field experience investigated land use through several activities, one of which helped students understand land cover changes in Connecticut over the last 30 years. A prior CAP lesson provided an introduction to geospatial technologies including geographic information systems, global positioning systems, and remote sensing technologies. Having increased familiarity with web-based mapping tools, students were well-poised to use Connecticut’s Changing Landscape (CCL) interactive map developed by the Center for Land Use Education and Research. Following a live virtual demonstration of the CCL website, students explored their own towns online and shared detailed findings with the group. Layering upon student awareness of landscape features, the faculty instructor and students discussed linkages between land use and the quantity and quality of water resources, plus the benefits of Low Impact Development (LID) practices to manage stormwater runoff (e.g., permeable pavement, green roofs, rain gardens). Students viewed a video demonstration of LID examples (e.g., porous pavement) and applied what they learned in a small group exercise adding LID features to maps of their high schools. A benefit of this CAP Land Use and Stewardship interactive, online activity is that students were able to create simulated LID plans for their school properties, instead of UConn’s campus, really “bringing the issue home” for them. Additionally, this activity helped several CAP students incorporate geographic mapping and habitat analyses using geospatial technologies into their conservation projects and presentations.

CTP Team Project Discussions

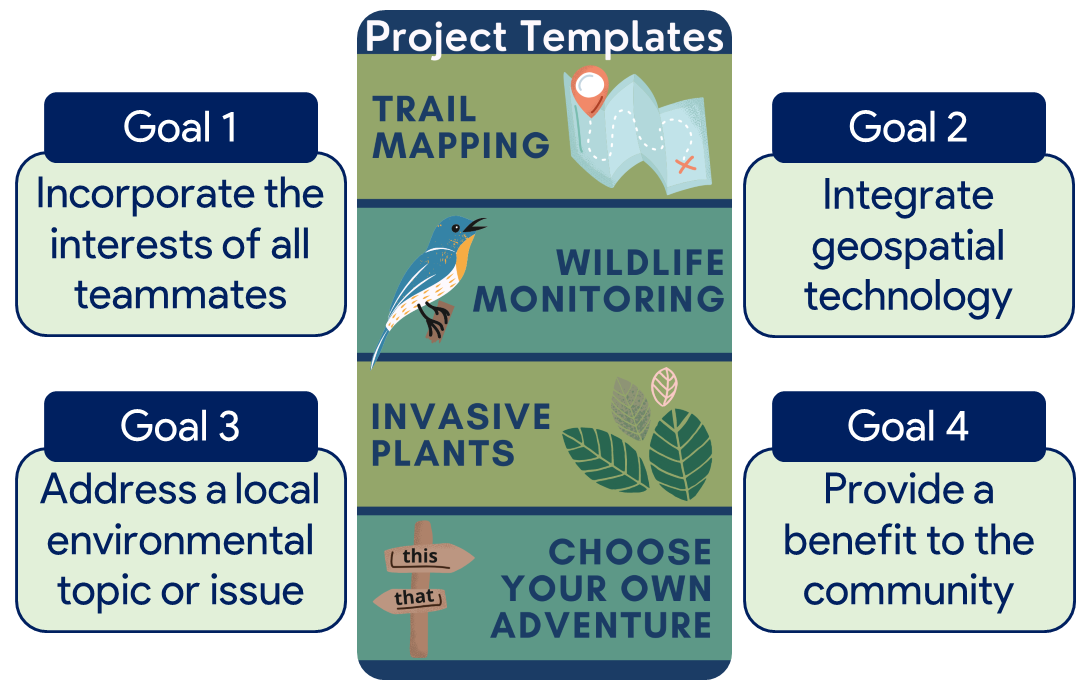

The intergenerational CTP teams spent considerable time during the two-day workshop, brainstorming and developing their local STEM conservation projects. During a whole-group presentation on day 1, participants learned about the goals of the conservation project and saw examples of past projects within four different topic areas aligned to CTP project development templates (Figure 6).

Following this introduction, teams met in breakout rooms for 40 minutes to simultaneously collaborate on a Brainstorming Team Conservation Projects Google Slides template. This activity helped teammates get to know more about each other, their (STEM and non-STEM) interests, and communities. At the end of the first day, attendees were encouraged to explore on their own the many diverse NRCA projects and associated products created by former participants via our filterable projects web page, which allows users to view and sort projects by topic, location, program, and type of technology used. Teams continued project development on day 2, during morning and afternoon sessions, for a total of 1.5 hours. They chose the topic area that best fit their project idea from the four options provided and worked through a Google Slides topic-specific project template document.

We increased our staff personnel to provide adequate instructor-to-participant ratios, such that each CTP team had a dedicated staff member to work with during the project development breakout sessions. We paired teams with staff members corresponding to project topics of interest, which allowed for scientific disciplinary expertise/guidance, relationship building, greater mentorship and guidance, more engagement from participants, and diversity of ideas and feedback. The smaller instructor-to-student ratio was possible with graduate student mentors and undergraduate interns.

Through these discussions, teams identified and shared to the whole group on day 2 their broad topic area, specific question and/or goal, project location, tentative timeline, final product, and next step. This also offered teams an opportunity to elicit additional feedback and resources for the projects they were planning to undertake.

Lessons Learned

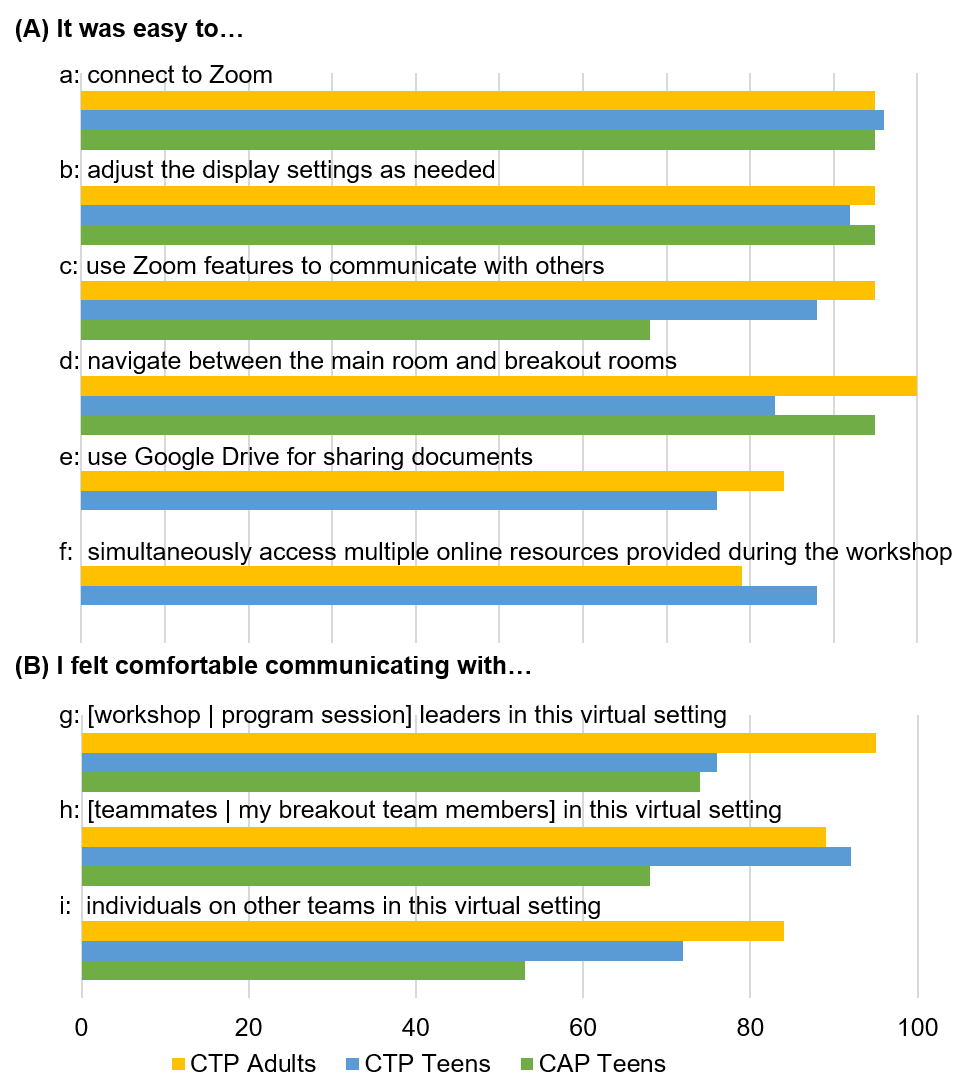

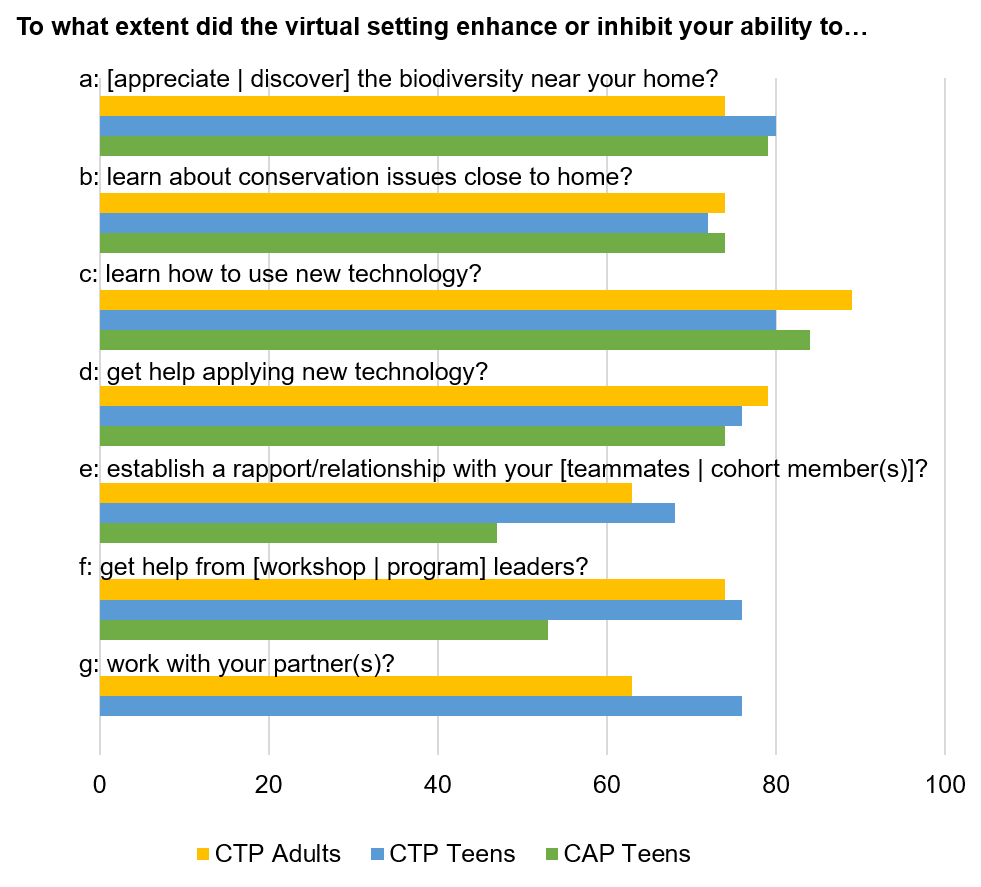

Transforming our environmental STEM field experience programs to an online experiential learning format was more successful than we expected it to be, but along with the success came unique challenges. To learn from this experience, we asked participants to provide feedback through anonymous post-program evaluation surveys regarding the ease of connecting to, using, and communicating through Zoom; navigating between the main room and breakout sessions, collaborating through Google Drive; and simultaneously accessing multiple online resources provided during the programs. We also asked participants the extent to which the virtual setting enhanced or inhibited their ability to appreciate biodiversity near their home; learn about conservation issues close to home; learn how to use new technology; get help applying new technology; establish a rapport/relationship with their teammate(s)/peer(s); and get help from program leaders. Online evaluation surveys were administered via Google Forms (CAP) and SurveyGizmo (CTP). Additionally, some CAP students answered open-response questions regarding the biggest benefits and/or downsides of participating in the program in a virtual setting. Likewise, post-workshop telephone interviews with six CTP adult participants conducted by an external evaluator (Horizon Research, Inc., Chapel Hill, North Carolina) provided further insight on their experiences in the virtual setting.

What Worked Well

Teen and adult participants indicated predominantly positive survey responses regarding the virtual setting of both NRCA programs (Figure 7). Most reported that it was easy to use Zoom and Google Drive and they felt comfortable communicating with program leaders through the video platform (Figure 7A). Over 70% of respondents indicated that the virtual setting enhanced their understanding and appreciation of conservation and biodiversity and their ability to learn and apply new technology (Figure 8). All six adult CTP interviewees indicated that the format worked well for them, with none of them citing any technical issues that interfered with their experience. As one stated:

“I thought [the virtual format] was fine. I think that given the circumstances, it worked out really well ... I thought there was good organization. The way they put it all together, the break-out sessions and all of that, it was excellent. It felt technologically refined and well managed.”

Half of the adult CTP interviewees stated that the virtual format offered other advantages such as allowing them to more easily see, and use, resources during the workshop. In the words of one:

“I think the virtual format was very, very, very effective. The presenters can share the screen, and then we could walk through on our own devices. So there’s a simultaneous or synchronous teaching and learning process that I thought was very effective.”

Including a variety of activities (e.g., interactive discussion, hands-on exercises) in different formats (e.g., whole group, breakout room, individual), in addition to playing music during breaks and pausing to have everyone stretch/move periodically, kept participants engaged in remote learning. When asked on the survey, “Was your experience in the CAP Virtual Field Experience what you expected?” several students said it exceeded expectations, such as one teen who responded, “It was far more fun than I thought it was gonna be online” while another shared, “I didn’t expect it to be so interactive. I was assuming that we would mostly listen to people talk in Zoom but we got to do lots of hands-on things as well.”

Using our participants’ homes as the learning space brought attention to the environment in their own backyard or nearby local area (e.g., neighborhood park) and enabled us to strengthen the connections between each individual and their immediate surroundings. Several responses to open-ended CAP survey questions shed light on student appreciation for this at-home, place-based learning approach. In response to the question, “In your opinion, what are the biggest benefits of participating in this program in a virtual setting?” students indicated that besides being comfortable at home, they “could test water and search for biodiversity near our own home and find out more about where we live and the wildlife around us.” A different teen wrote, “We could see what’s going on around us rather than miles away.” Regarding aggregated activity results using Epicollect5, a third CAP student added that, “We all got to see the differences in wildlife and water depending on where in the state we lived.” While the pivot to a virtual setting impeded traditional NRCA field activities, individual, at-home exploration afforded an increased opportunity to connect participants to their proximate surroundings, allowing familiar and personal spaces to become new outdoor or environmental STEM learning spaces (Iyengar and Shin 2020). Participating from home also provided an opportunity to those who may have limited access to traditional in-person programs (e.g., those who lack transportation). An adult CTP interviewee noted that the virtual format was more convenient than attending a face-to-face workshop: “I think, personally, it worked out better.... I didn’t have to find childcare. I could stay at home. I could work in my house. I didn’t have to worry about commuting anywhere.”

What Was Challenging

One of the first major obstacles we attempted to overcome was ensuring that participants had adequate access to technology and reliable internet. Despite providing technology resources to individuals who indicated need for them (e.g., laptop, mobile hotspot), a few program participants, unfortunately, still experienced poor video quality, limited audio, and interrupted connectivity. Even those with “good” internet access can experience occasional hiccups that have the potential to disrupt the distance learning experience.

Another problem we struggled with was the reduced ability of our instructors to effectively help participants beyond instruction, to troubleshoot issues they were having. For example, using a mobile app like Epicollect5 for the first time. During in-person programs, an instructor can easily look over someone’s shoulder and explain which buttons to tap, but this was not possible while communicating through screens, especially during whole-group activities when a participant may not feel comfortable interrupting to ask a question or get help. Although we were able to address most problems as they arose, we would have benefitted from slowing the pace of instruction and having a dedicated staff member to assist individual participants with troubleshooting technology and other issues. This could be done by meeting with individuals in a breakout room and/or being “on call” and available during technology-focused activities.

Our most difficult challenge was not revealed until after the remote programs concluded and we were able to review responses to post-field experience surveys and phone interviews conducted by our external evaluator. Not surprisingly, the richness of personal interactions was likely compromised by the unavoidable virtual format (Figure 8). For example, one adult CTP participant stated,

“I imagine that in previous years, being in a group outside, interfacing live or in person, probably would have [us] get a little bit more out of the experience.... In our experience, there didn’t seem to be that many questions and back-and-forth interaction, which would help to support the learning process.”

Similarly, one CAP student wrote in their post-field experience survey, “I felt less connected to my peers.” Another CAP student indicated that the communication challenge was broader, “It was harder to connect and talk to other members and team leaders in the Zoom call.” Candid responses like these will be valuable in guiding future NRCA programming efforts that use remote learning formats.

Conclusion

Transforming a traditional field-based program with teen and adult participants into one that is primarily delivered online can be quite challenging. Despite numerous obstacles posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, we had the resources and personnel that enabled us to provide quality, informal environmental education programs remotely to a total of 48 teens and 22 adults. While the positive feedback from our participants is evidence of our ability to successfully deliver immersive place-based STEM learning experiences through an online learning model, there is room for improvement. We hope that the valuable lessons learned during our pivot to online programming will assist educators in both formal and informal place-based STEM education settings.

In future online NRCA programs, we will aim to increase the rapport among participants by providing additional opportunities for peers and teammates to connect and create stronger relationships. Certainly, in-person interactions are difficult to replicate and an online interface is less personable. Yet, opportunities for peer and peer-to-instructor interaction are possible through small groups (e.g., breakout rooms) and through parallel modes of communication (e.g., chats, Slack, WhatsApp), and can be used to build critical social bonds by providing real-time opportunities for students to directly communicate during a program. We also realize that enhanced preprogram, online team-building opportunities would have helped to build the much-desired participant connections that postprogram survey respondents indicated they missed.

Acknowledgments

The CTP program is supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant AISL-1612650. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The CAP program is primarily funded through private giving and leveraged with support from various university departments. Extramural support comes from an anonymous private foundation, the Goldring Family Foundation, and the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Connecticut. Intramural support comes from the University of Connecticut Department of Natural Resources & the Environment, the Center for Environmental Sciences & Engineering, and the Institute of the Environment. We wish to thank external evaluators Dr. Joan Pasley and Dr. Keith Esch from Horizon Research, Inc. for their guidance and feedback on the CTP education programming, integrated research, and evaluation.

Nicole Freidenfelds (nicole.freidenfelds@uconn.edu) is a Visiting Assistant Extension Educator, Laura Cisneros is an Assistant Extension Professor, Amy Cabaniss is a Visiting Assistant Extension Educator, Rebecca Colby is a Doctoral Candidate, Madeleine Meadows-McDonnell is a Doctoral Student, and Ankit Singh is a Doctoral Candidate, all at the University of Connecticut - Natural Resources & the Environment in Storrs, Connecticut. Todd Campbell is a Professor, David Moss is an Associate Professor, and Jonathan Simmons is a Doctoral Candidate, all at the University of Connecticut – Neag School of Education in Storrs, Connecticut. Chester Arnold is an Extension Educator, Cary Chadwick is an Extension Educator, and David Dickson is an Extension Educator, all at the University of Connecticut – Center for Land Use Education & Research in Haddam, Connecticut. John Volin is the Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost at the University of Maine, Office of the Provost & School of Forest Resources in Orono, Maine.

citation: Freidenfelds, N., L. Cisneros, A. Cabaniss, R. Colby, M. Meadows-McDonnell, T. Campbell, C. Arnold, C. Chadwick, D. Dickson, D. Moss, J. Simmons, A. Singh, and J. Volin. 2022. Pivoting during a pandemic: Transforming in-person environmental stem field programs into immersive, online experiential learning. Connected Science Learning 4 (2). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-march-april-2022/pivoting-during-pandemic

Citizen Science Environmental Science Research Technology Informal Education