Facilitating Emancipatory and Justice-Centered Environmental and Climate Learning

Connected Science Learning September-October 2021 (Volume 3, Issue 5)

By Pranjali Upadhyay and Rae Jing Han

In recent years grassroots, youth-led movements have increased our collective awareness of the need to incorporate transformative action and justice into efforts to address environmental degradation and the global climate crisis. These movements are often led by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), LGBTQIA+, and multiply marginalized youth, and tend to frame social, economic, political, and environmental and climate justice as interconnected issues (e.g., Intersectional Environmentalism, Zero Hour, Sunrise Movement). In amplifying the urgency of climate change response on local, regional, and national scales, these movements have also highlighted the power of youth voice, agency, and leadership. As educators, we have a responsibility to be adult allies who honor and uplift the work of the young people with whom we work, play, and learn.

Our approach to crafting justice-centered and emancipatory educational experiences involves engaging students in problem solving that addresses authentic challenges and critical events grounded in both local and global real-world contexts. To be emancipatory, STEM education must lead students to reach a deeper and more functional understanding of their world—an understanding that allows them to advocate for their community’s well-being and sociopolitical transformation (Calabrese Barton and Tan 2020; McKinney de Royston and Sengupta-Irving 2019; Morales-Doyle 2017). The true purpose of education is more than skill and knowledge development; it is the ignition of a lifelong process that nurtures every aspect of the child and empowers them to make positive changes in their lives (Birmingham et al. 2017; Du Bois 1903; Freire 1970).

This article illustrates how curriculum design and professional learning efforts can support emancipatory and justice-centered environmental and climate learning for students of all ages by using a case study from southwest Washington state. To accomplish this, we

- share several overarching design stances that guide this work;

- draw on insights from two case studies of work within the ClimeTime initiative, including a K–5 interdisciplinary STEM curriculum project (with freely accessible units to implement or use as models) and a secondary climate justice professional learning community; and

- describe content considerations and pedagogical principles that educators can consider implementing to support justice-centered and consequential learning, critical consciousness, and transformative agency in environmental and climate learning.

Shifting Power for Socio-Ecological Transformation

Empowering students is a common goal expressed by educators and educational leaders when discussing the purpose of education. However, power hierarchies and deficit assumptions are deeply embedded in our society and thus show up in classrooms and in our educational systems, inhibiting student agency and authentic engagement. For students, deficit mindsets often take the form of developmental appropriateness discourses in which the default position is “Can students handle that?” For example, the idea of “ecophobia” is prevalent in mainstream environmental education and climate change education, claiming that children should learn to love nature before they are asked to save it. Concerns about developmental appropriateness, while well-intentioned, tend to be rooted in narrow views of young people’s capabilities and Euro-Western constructions of childhood innocence that gaslight the experiences of children of color. These assumptions are also expressions of structural privilege and deny the lived realities of children, youth, families, and communities who are already navigating and taking action within worlds shaped by racialized injustices, socioeconomic challenges, environmental harm, and shifting climate systems.

For many students, these interconnected issues are urgent and immediate, not topics to be deferred until students are “ready” to engage. For these reasons, dominant forms of environmental and climate education often alienate and disenfranchise youth of color, youth experiencing poverty, and other young people who live at the intersections of multiple marginalized social identities. By avoiding discussion of sociopolitical, environmental, and climate realities and students’ emotional responses to these realities, we are protecting the comfort of those in positions of power and privilege at the expense of those at society’s margins. If many children are experiencing these impacts in their daily lives, then all children can and should learn about these issues. Although marginalized communities have always led intersectional resistance and liberation efforts (e.g., environmental justice, labor organizing, abolition and civil rights movements), the heightened visibility of youth-led and BIPOC-led climate justice movements in recent years urgently demands that we as adults listen and respond.

Case Studies: STEM Storylines and the Climate Justice League

The insights we offer in this article are grounded in relationship-building and collaborative learning with students, teachers, and community leaders and organizers across multiple years. In particular, we focus on learnings that have emerged within and across the STEM Storylines and Climate Justice League projects.

STEM Storylines are K–5 units that structure learning around bundles of NGSS and the science and engineering practices as well as transdisciplinary integration with other subject areas such as English language arts and math. Each STEM Storyline is iteratively co-designed with K–5 teachers and engages students in sustained problem-based learning and inquiry centering a focal phenomenon and driving question. Opportunities for meaningful community engagement are woven throughout, from learning with community scientists to collaboratively designing public-facing action projects to address the focal challenge. Students’ experiences, voice, interests, and expertise are centered in and drive the collective learning process.

The Climate Justice League is a professional learning community that supports secondary educators in facilitating science learning experiences at the intersections of social, environmental, and climate justice. To highlight the voices and perspectives of experts from marginalized communities, cohorts of teachers engage in shared learning about climate justice issues and the solutions, science-related practices, resistance, activism, and transformation led by frontline communities. Building on these foundational understandings, teachers design and implement justice-centered science learning activities that are locally salient and consequential for their students, then share these efforts with fellow educators in the cohort. In addition to the benefits of co-constructed critical reflection and peer learning, the collaborative community formed through Climate Justice League has become a space of support, solidarity, and strategizing as teachers navigate the overlapping challenges that emerge when working to center social justice in their practices.

Design Stances That Guide This Work

In our justice-centered projects, we work to directly confront the power imbalances embedded within educational systems and shift toward empowerment for both students and teachers. This calls for explicit attention to role remediation (Bang and Vossoughi 2016) through repositioning teachers as expert co-designers and leaders and repositioning young people as scientific thinkers and doers, ethical deliberators and decision makers, empathetic caretakers, and capable agents of change (see Learning in Places; Learning for Justice’s Social Justice Standards). From this stance, STEM learning is also fundamentally a political endeavor that deeply matters to the current and future lives of all.

Topics related to sociopolitical, environmental, and climate justice are complex and must be approached with intentionality and through pedagogical approaches that resonate with the interests, prior experiences, and expertise that students and their communities bring to learning (see Saint-Orens and Nxumalo 2018, Climate Action Childhood Network, and Common Worlds Research Collective for examples from different contexts). Our design stance is student-centered: Learners themselves choose what to learn to dig deeper into focal problems and make sense of driving questions. Rather than doing prepackaged activities and experiments, students engage with problems and issues that are meaningful to them and their communities. Key scientific concepts and principles are uncovered as they relate to a real-world phenomenon, and students construct a functional, contextualized understanding of science.

Through facilitating and participating in these distinct but cross-pollinating project spaces, we have seen how our core design stances can support youth and educator empowerment and their sustained and expansive engagement in justice-centered learning and action. In particular, we want to emphasize that this work is lifelong: Opportunities to meaningfully engage with social, environmental, and climate justice issues are critical across the early childhood, elementary, secondary, and adult years.

Content Considerations

A key dimension of emancipatory, justice-centered environmental and climate learning is centering curriculum on salient justice-related phenomena and opportunities to learn from the leadership and knowledge of frontline communities.

Integrating Authentic Local and Global Phenomena

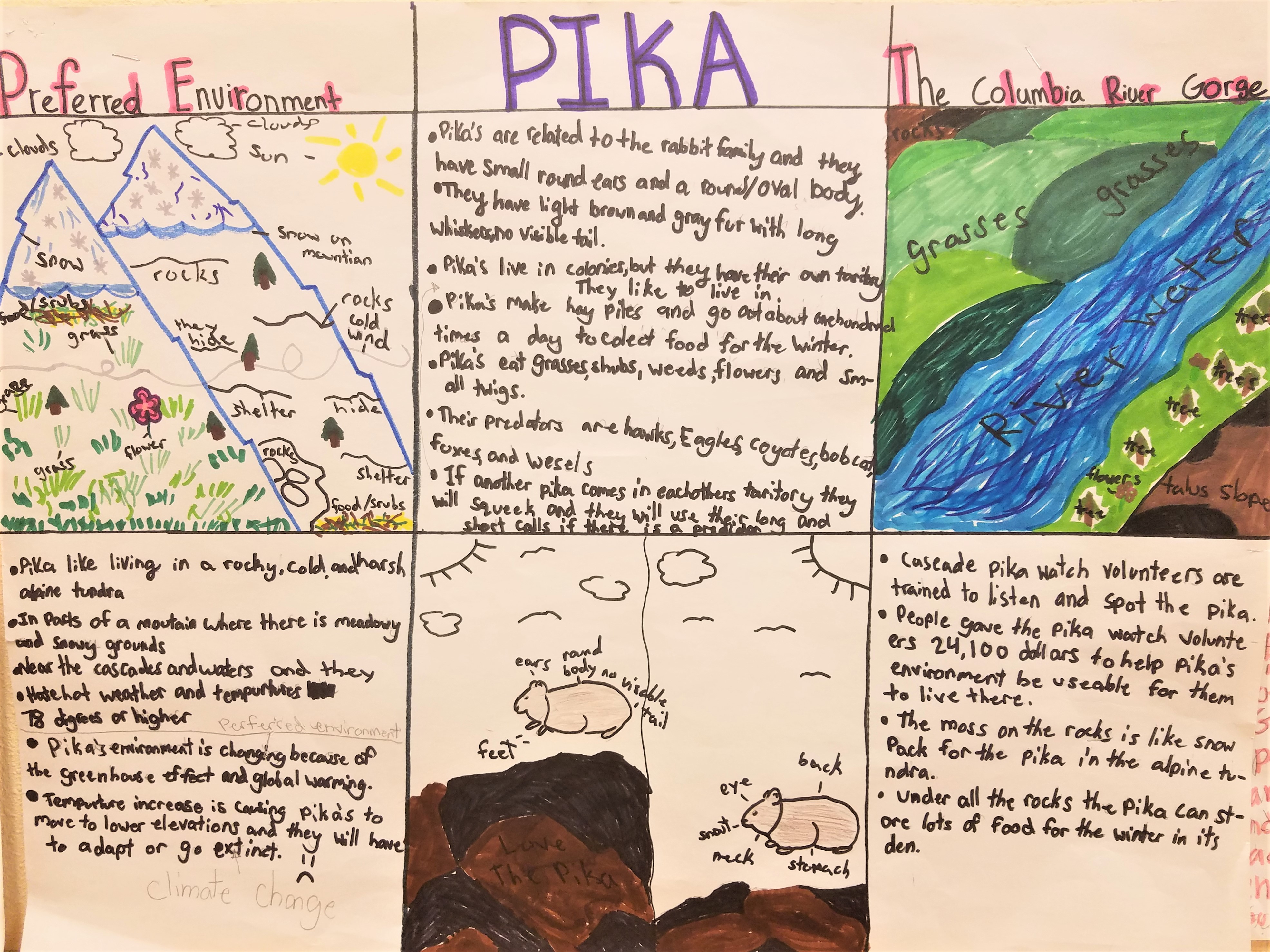

Examining the ways in which humans have encroached upon and affected local ecosystems, or the ways in which climate change manifests itself in a local community, can ignite an intrinsic curiosity and interest in science content. For example, there are Storylines that explore the driving questions “How can we create a campaign to help preserve the pika in the Columbia River Gorge?” (see Figure 1 for an example of student work from this Storyline) and “How can we help preserve the endangered western pond turtle in WA?” (see examples of student work). Another STEM Storyline focuses on the phenomenon of beach erosion on Washington’s coast caused by rising sea levels due to climate change.

As in many of our units, students engage in a series of investigations and research to better understand a phenomenon so they can engineer a solution to aid people or populations in crisis. Presenting students with opportunities to solve real problems in their community can foster youth leadership capacity (Mitra 2014) while framing challenging and complex issues through an action- and solution-oriented lens. This focus on imagining solutions can help build students’ sense of agency and steer them away from outcomes of anxiety and despair. Many of our students reside in communities that are inescapably affected by climate change in these and other ways. If we fail to provide students with opportunities in our classrooms to critically engage with these problems, we neglect our duty of preparing youth to survive and thrive in our current and future realities.

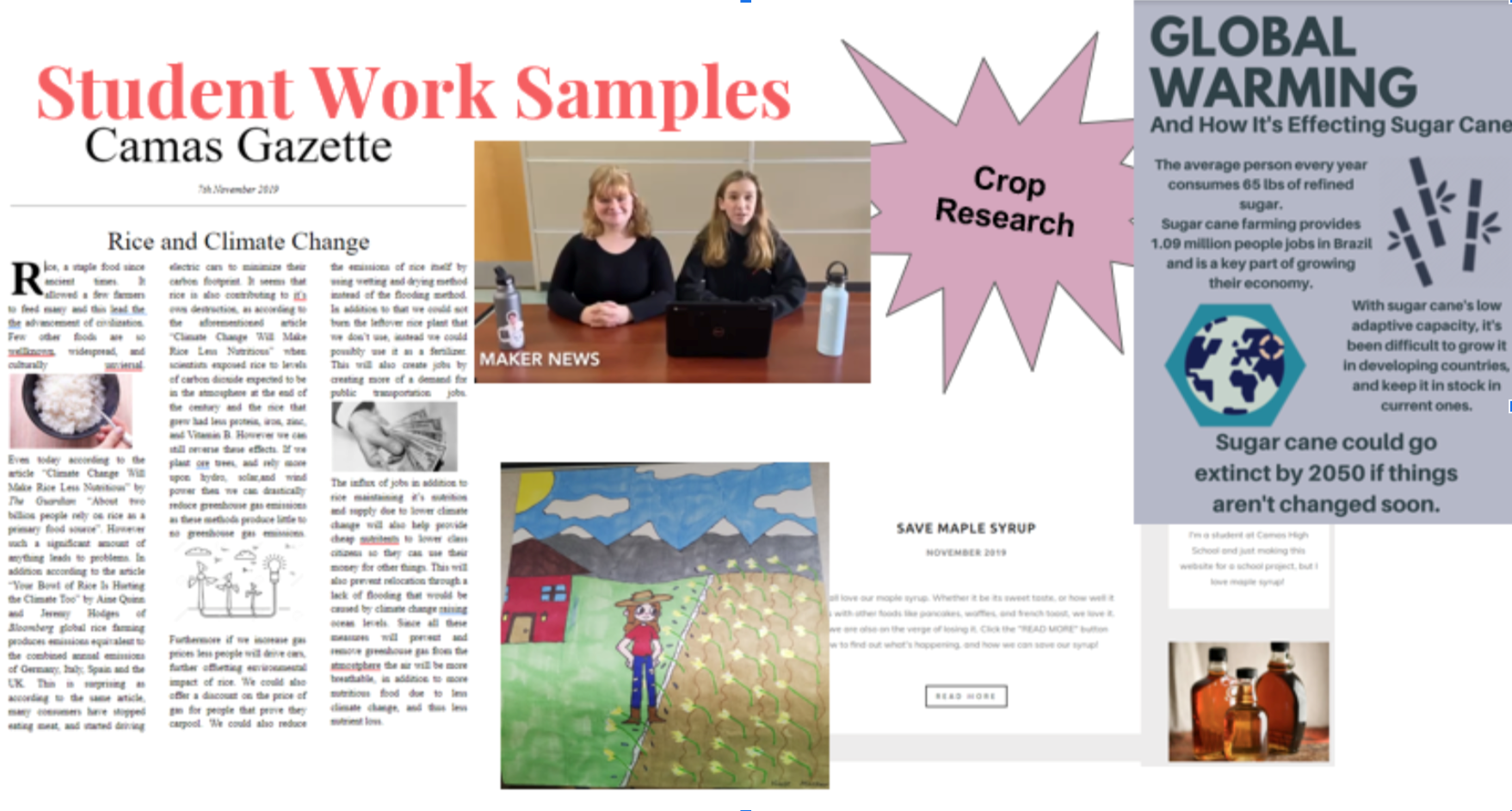

While local phenomena are a great way to engage young learners in relevant STEM learning, global crises are sometimes dismissed by STEM curriculum developers who aim to focus on students’ immediate and tangible realities. We believe that engaging students in understanding the impact of globalized capitalism and its legacy of exploiting and hurting marginalized communities is essential in developing environmental and climate literacy that is anchored in social justice. Intersectional environmentalist perspectives highlight the ways in which individual, local, regional, and global environmental health are deeply connected. Therefore, we see the value of connecting students to the realities of global frontline communities who continue to resist oppression and persist for the liberation of people and the environment. For example, a middle school Storyline designed by teachers who participated in the Climate Justice League explores issues of water scarcity and justice by investigating patterns and differences across regions (see Figure 2). Another Climate Justice League teacher facilitated student learning about global food justice and agricultural challenges exacerbated by a changing climate (see Figure 3). Through learning experiences that highlight global interconnectedness, we support students to develop a critical awareness that helps them understand ways that their actions can be restorative and responsible instead of further perpetuating inequities and injustices against marginalized communities.

Centering and Amplifying BIPOC Perspectives and Expertise

Centering global environmental and climate phenomena also creates a space where the perspectives and stewardship of Black, Indigenous, and other global majority (Souto-Manning and Rabadi-Raol 2018) communities can transform the ways in which students perceive and connect with their world. For instance, our recent fifth-grade STEM Storyline challenges students with the driving question, “How can we learn to be better protectors of the Earth?” Instead of positioning marginalized communities as helpless and cultivating a savioristic frame of reference for our students, this unit highlights the longstanding leadership and activism of BIPOC communities so that the valuable contributions of intersectional environmental activism can be celebrated. At the same time, a commitment to climate justice and social activism should not fall solely on the shoulders of communities of color. It is important to support our non-BIPOC students by reframing the deficit-based and Eurocentric narratives that have dominated the STEM education space and have dismissed Native science and Indigenous activism as folklore (Medin and Bang 2014). Our centering of BIPOC voices and perspectives is a strategic move beyond dominant Euro-Western forms of environmentalism to amplify non-dominant culturally situated socio-ecological relations.

In “Becoming Protectors of the Earth,” we initiate the project by highlighting the environmental stewardship of Jessica and Sammy Matsaw (Shoshone-Bannock) and help students see how cultural, spiritual, and community connections with the environment are central in protecting the Earth. Students learn from young activists Xiye Bastida (Otomi-Toltec) and Maxine Jiminez as they highlight problems affecting their communities while inspiring hope for a brighter future. They engage in a Climate Justice Mixer activity (adapted from the Zinn Education Project) designed to showcase how leaders around the world are responding to the climate crisis. Students explore the Climate Stories map from Our Climate Our Future to understand how other young people are experiencing climate change and taking action in the climate movement. As students begin thinking about creating a public product designed to instigate change and bring awareness to their communities, they listen to the powerful poem, “Rise: From One Island to Another,” written and orated by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner (Marshallese) and Aka Niviâna (Inuk). This passionate and beautiful performance shows students the pervasiveness and interconnectedness of the climate crisis while showing the power of solidarity between people across the globe in empowering change.

After listening to the messages of each activist, students are asked what they learned about the problem, how they felt after listening to their stories, and how these individuals are using their voices in different ways to advocate for positive change. Students also reflect about how these stories provide either a mirror to understand their own life experiences more deeply, or as a window through which to view someone else’s reality. By highlighting the voices of youth activists of color who are naming their realities, we create an opportunity for discussion about inequities in society. For instance, after hearing Maxine Jiminez speaking about the impact of heat and pollution on her community located in Los Angeles, students explicitly consider why some communities are disproportionately affected by air pollution and rising temperatures. The discussion urges teachers and students to consider the ethical considerations of these injustices, allowing for the expansion of one’s own finite worldview and the cultivation of a critical awareness.

STEM education has a history of perpetuating oppression through the exclusion and invisiblization of BIPOC scientists and scientific practice. The celebration of BIPOC scientists, scholars, activists, and communities who have contributed to environmental and human restoration is essential in decolonizing the field of STEM and paving the way for truly equitable outcomes for marginalized youth. This is also an essential shift toward culturally sustaining pedagogy that explicitly supports and deepens learners’ participation and sense of belonging in dynamic cultural communities (Paris and Alim 2017).

Pedagogical Principles

In addition to thoughtful curricular design choices, emancipatory and justice-centered environmental and climate learning requires intentional shifts in pedagogical practice to support student agency and leadership in the classroom, as well as in families and communities.

Project-Based and Student-Centered Approaches to Explore Complex Justice Issues

Several pedagogical principles guide our curriculum development and implementation, which aim to create emancipatory spaces for our learners. We have adopted the instructional framework of Project-Based Learning (PBL) to create spaces where students can sense-make about phenomena while building leadership capacity within their class and community.

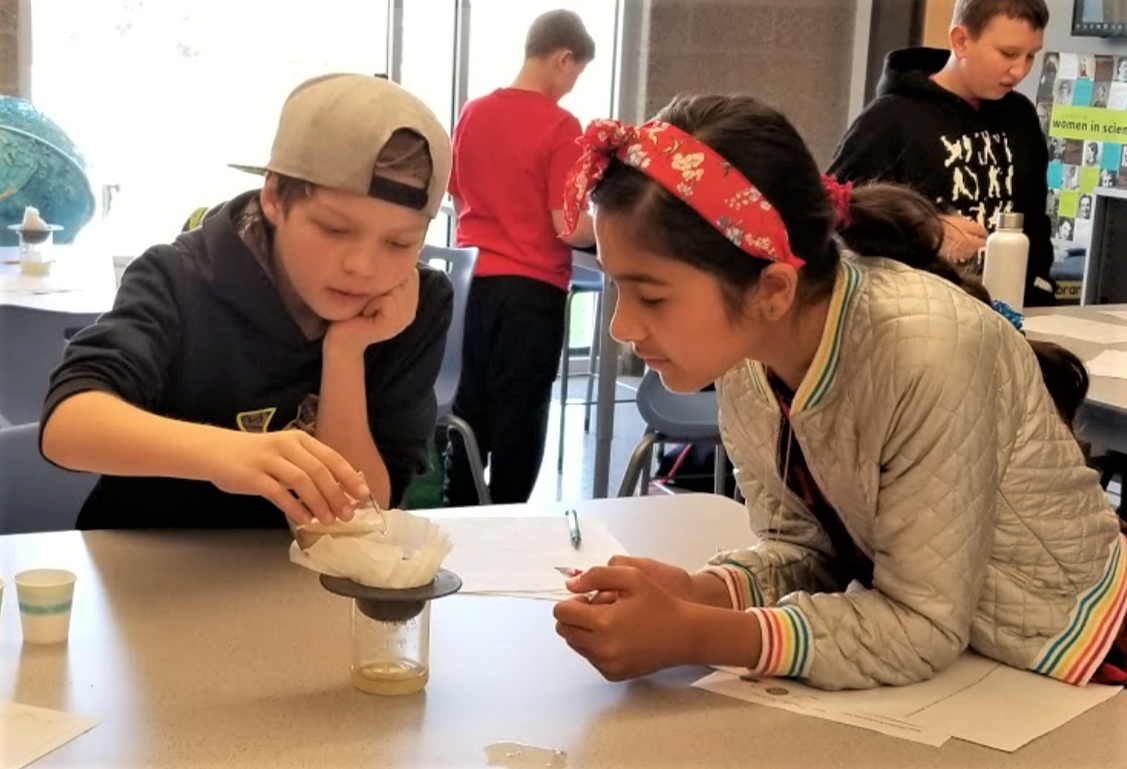

Each Storyline begins with the unveiling of a relevant anchoring phenomenon (e.g., local coastal erosion), which aims to sustain inquiry for several weeks or months. During a collaborative brainstorming process, the educator selects the phenomenon by considering their students’ interest, grade level, and alignment with NGSS standards. When the phenomenon is first unveiled, students engage in a “notice, wonder, know” protocol (see Figure 4) where they share their observations, questions, and prior knowledge about the problem they will be solving (which exists in the form of a “driving question”). Each student contributes in some way, whether verbally, in writing, through drawing, etc. Students' funds of knowledge (González, Moll, and Amanti 2006) are celebrated, while their inquiries are brought to the forefront with the teacher using their wonderings to drive the learning experience.

Collective and Collaborative Sense-Making

The units continue with a sequence of discussions in various formats in which learners are collectively sense-making about the topic and connecting their learning to the driving question. There is an intentional stepping away from a banking model (Freire 1970) where students are given information by the teacher. Instead, students engage in an active struggle to reach a deeper understanding of a phenomenon. We provide a variety of discussion prompts to help the teacher open up rich science conversations in the classroom (see Figure 5 for an example). Conversations also attend to social-emotional dimensions of learning, such as students’ emotional responses to the ideas they are hearing about and discussing. The role of the teacher in these moments is simply as a facilitator of dialogue and a co-creator of knowledge. We urge teachers to reconsider the perception that science is a collection of facts and instead encourage multiple ways of knowing and thinking about science.

Learners also engage in sense-making through scientific modeling and argumentation. The learning experience includes the creation and iterative refinement of individual models and team consensus models (see Figure 6, Figure 7, and Figure 8). Argumentation is used in a similar way as a tool for students to process, self-reflect, and expand on their understanding and is not necessarily a summative indicator of learning.

Uplifting Student Voice, Leadership, and Agency in Community Contexts

Importantly, student voice, leadership, and agency are affirmed throughout the Storyline learning experience. For example, students are often referred to as experts within their learning community, are supported to deepen their expertise on a topic, and are invited to share this expertise with their classmates as active participants in a community of learners (see Figure 9). Students are explicitly reminded about the importance of their voice (see Figure 10) and asked to explain their thinking and learning through different forms of communication (see Figure 11).

In addition to positioning learners as capable scientists and leaders, the Storylines support teachers to connect students with local community experts and STEM professionals. For example, in the second-grade Storyline “Why Won’t Our Blueberries Grow?” students are introduced to Shanelle Donaldson West, an urban farmer, food justice advocate, and co-founder of Percussion Farms (see Figure 12). They explore some of the authentic considerations and challenges that Shanelle faces in her farming practice. Through learning experiences like this, students are exposed to non-dominant, justice-centered forms of environmental relationality and stewardship. At the same time, connecting with BIPOC community leaders and experts can support students of color in envisioning themselves pursuing STEM-related activities and pathways and engaging in different forms of community action and leadership.

Each Storyline culminates in an action project in which students synthesize what they have learned by creating a product that addresses the core challenge or communicates their knowledge with an authentic audience (e.g., scientists, community members, school staff, etc.; see Figure 13). By inviting students to take action focused on collective and systemic acts of restoration, the Storylines convey an affirmation that transformation from harm toward justice is possible and that young people can contribute meaningfully to these shifts in their communities. [Author Note: When collaborating with community members, please attend to safety-related policies in your school context and coordinate with school leaders to ensure student well-being.]

Shifts in Thinking and Practice

In our collaborations with teachers across the STEM Storylines and Climate Justice League projects, we have noticed that moves to integrate the design stances, content considerations, and pedagogical principles outlined above are often connected to fundamental shifts in educators’ thinking and assumptions about teaching and learning. These shifts in thinking and practice are shaped by educators’ identities and positionalities. For example, in the Southwest Washington region the majority of teachers are white (more than 90%), whereas a significant proportion of the students they serve are people of color. These shifts strengthen teachers’ abilities to facilitate learning communities in which students can enact agency over what and how they come to know about environmental and climate issues through authentic and consequential learning.

Shifting Disciplinary and Transdisciplinary Understandings

Despite the emphasis on science and engineering practices in the NGSS, many curriculum materials implicitly portray science as a linear and formulaic process governed by “the scientific method.” These static conceptions of science are evident, for example, in the prescriptive step-by-step instructions and close-ended labs or experiments that remain common, especially for younger learners. In conversations with teachers who are implementing STEM Storylines or designing their own climate justice learning activities, we have seen important pivots in these ideas about the nature of scientific processes. Specifically, teachers articulate emergent and dynamic conceptions of science learning that center problem-solving, dialogue and discussion, iterative modeling, and collaborative sense-making.

In addition to their shifting understandings of science as a discipline, teachers have described how their engagement in justice-centered learning and design work has deepened their ability to support transdisciplinary learning opportunities. In these project spaces, teachers have found that socio-political issues impacting our local and global communities are meaningful contexts for rigorous science learning. This is a critically important transformation for science educators, who are often trained to pride themselves on adhering only to “objectivity,” “neutrality,” and “facts.”

Given the heightened rigidity and pressures of the current educational system, science is often sidelined to focus on English language arts and math learning—especially in elementary classrooms and in schools serving large numbers of low-income students and students of color. The STEM Storylines and Climate Justice League both intentionally interweave multiple ways of knowing, including linguistic, mathematical, creative, and social-emotional repertoires of practice. Teachers often shift from viewing science learning as an additional obligation in an already-packed school day to recognizing that complex socio-scientific phenomena like community health and wellbeing, climate change, and ecological systems are powerful contexts in which to support students’ practices across multiple interconnected disciplines.

For example, one elementary teacher who implements the STEM Storylines as well as other project-based learning experiences shares:

With science, [...] that’s where you integrate your math and your reading. I mean, that’s where, it’s the puzzle that you are putting all those pieces together. So teachers who are spending six hours a day teaching them math and the reading, the only way to fit it together and to get it to stick is through projects and through science and through those real-world connections. And, you know, that’s the impact.

Shifting Toward Asset-Based Conceptions of Learners

Beyond these content-related shifts in thinking, project-based and justice-centered approaches to environmental and climate learning are also associated with shifts from deficit- to strengths-based ideas about students. For example, teachers often hesitate when transitioning from traditional, scripted science activities to student-centered models because they fear that their students are not adequately prepared for such rigorous forms of scientific inquiry and real-world problem solving. These kinds of deficit assumptions are especially common in the elementary years and in classrooms with high numbers of low-income students and students of color.

In contrast, teachers who are experienced designers and facilitators of project-based learning express asset-focused views of students—including the youngest learners—as capable intellectual thinkers, doers of science, and impactful community leaders. In addition, they intentionally work to cultivate students’ sense of empowerment through engagement with Storylines and other forms of project-based learning. One teacher describes:

There was a shift about mid-unit where kids started to, they would call themselves the scientists, like they started to see themselves in that role a little more, and I don’t think I’ve seen that so quickly in the fifth grade year, where I’m, I’m training them in PBL, and giving them that autonomy and pumping them up of “You know what, your voice matters. You can make a difference and this matters.”

Shifting Sense of Professional Identity as a Facilitator and Co-Learner

In addition to shifting beliefs about their students, teachers also often alter their conceptions of their own professional identities. Our teacher collaborators share that their colleagues often feel a sense of insecurity when moving from scripted curriculum to a more open-ended, emergent, and unpredictable shared exploration of phenomena. For many teachers, facilitating student-driven, project-based learning requires them to critically examine the roles they’ve been trained to play in classrooms—as authority figures and knowledge-holders—and instead adopt a stance of humility and comfort in not having pre-established answers. One teacher reflects on her commitment to learning together with students:

I think that idea of, as teachers being okay with not knowing everything, and admitting that they don't know everything, is something that I really actively try to do in all areas of my practice because, again, I really believe in authenticity, and as an adult, do you know how many times I Google things a day ’cause I don’t know them? I’m not the keeper of all knowledge. And part of my identity is not being the keeper of all knowledge. And I think that’s also part of it is learning with kids and showing kids that you don’t, as an adult, you’re not going to know everything, and that’s totally fine. And guess what, there are ways that we can figure it out, so let’s go do that!

Shifting Classroom Power Dynamics and Entrenched Assumptions in Educational Systems

These interconnected shifts in teacher thinking and practice reflect the need to disrupt the power dynamics that shape classrooms and imagine different possibilities for building a community of co-learners. Most young learners enter science experiences with innate curiosity, excitement, and empowerment. Unfortunately, the rigid ways in which Euro-centric perspectives have denoted what represents true science can be disempowering to our learners, especially when learning is centered around the teacher’s expertise. We should support teachers to critically attune to and dismantle the ways that these pervasive power imbalances manifest in their curriculum design processes and in their ways of learning alongside students in and beyond the classroom.

Educational leaders and PD providers should support educators to facilitate justice-centered environmental and climate learning that is responsive to the interests and concerns of their students and communities. To do so, they must engage in meaningful co-design processes that honor teachers’ expertise and knowledge, youth voice and agency, and community leadership. This might entail, for example, partnering with teachers to create resources that are highly usable and relevant for them; reconsidering the structure of a school day, week, and year; rethinking how family and community engagement is conceptualized and enacted in schools; and building caring relationships with lands and local places. These systemic shifts also necessitate the prioritization of sustained relationship-, community-, and solidarity-building among teachers to support their ongoing learning and reflective practice.

Concluding Thoughts

As we enter a new era of ecological and climate-related crises, and as urgent realities of social injustice continue to resonate in our collective consciousness, our youth face a world filled with unfamiliar and seemingly insurmountable challenges. As educators, we hold the responsibility to help our students develop the intellectual capacity and critical awareness to navigate their socio-ecological contexts. Young learners who sit in our classrooms possess the potential to reimagine and rebuild our future profoundly and positively if they experience epistemic agency to engage with consequential real-world problems. However, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students often experience curricula that elicit submission instead of fostering leadership and critical thinking (Darling-Hammond 2018).

The use of real climate and environmental crises being endured by marginalized communities is a key instructional element of STEM education that advances equity and social justice. If toothpick towers, vinegar volcanoes, and other fun but contrived activities comprise the bulk of STEM experiences for our students, then we deprive students the opportunity to engage in more complex and unsettled ways of knowing and doing science. We also reflect on a threat of STEM education becoming so centered around technical skills and future workforce development that it ignores our students’ current participation in and interactions within a deeply interwoven world. Preparing students to face the realities of the world they are inheriting is an act of intergenerational solidarity and equity, which is needed to reimagine a future that is environmentally sustainable and socially just.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Stacy Meyer, Meredith Lohr, and Deb Morrison for their thoughtful insights and feedback throughout this writing process. We are also grateful for the generosity, leadership, and ongoing collaboration of teachers in Southwest Washington. Thank you to the brilliant youth activists who continue to impact and empower educators and future generations of learners.

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) through the ClimeTime initiative and by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1626365. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funder.

Pranjali Upadhyay is an Integrated Curriculum Coordinator at Educational Service District 112, in Vancouver, Washington. Rae Jing Han (racheljing.han@gmail.com) is a PhD Candidate and Graduate Researcher at University of Washington, Institute for Science + Math Education in Seattle, Washington.

citation: Upadhyay, P., and R. Jing Han. 2021. Facilitating emancipatory and justice-centered environmental and climate learning. Connected Science Learning 3 (5). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-september-october-2021/facilitating

Citizen Science Climate Change Environmental Science Equity STEM Middle School Elementary High School Informal Education