Diversity and Equity

Codesigning With Indigenous Families and Educators

Creating Robotics Education That Contributes to Indigenous Resurgence

Connected Science Learning July–September 2020 (Volume 2, Issue 3)

By Carrie Tzou, Elizabeth Starks, Meixi, Amanda Rambayon, Sara Marie Ortiz, Shawn Peterson, Paradise Gladstone, Ellie Tail, Arianna Chang, Elise Andrew, Xochitl Nevarez, Ashley Braun, Megan Bang

What have you learned from a plant?

What patterns do you see in the plants, water, sky, and animals?

How might you program LEDs to illuminate your design?

These are a few of the prompts from a family engineering guide designed by Native Girls Code, a club for Native girls age 12–18, who were also integral partners in our project. In this article, we describe the ways in which our model of partnership opened up new and sometimes unexpected avenues for agency, as partners’ roles shifted and evolved over the course of our four-year project.

Increasingly, informal STEAM-based (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) learning environments are working toward becoming sites of equity-focused work (cf. Calabrese Barton, Tan, and Greenberg 2017). Over the past four years, we have built and nurtured a partnership between university researchers, public librarians, science center practitioners, Native American community organizers and educators, and families to codesign TechTales and TechStyle Tales. These two workshop series and associated activities are designed to support families in remaking their relationships to technology and generatively contributing to cultural practices in their communities (Vossoughi, Hooper, and Escudé 2016). Overall, the project has designed these two workshop series (one using robotics and one using e-textiles), a series of “booster days” designed to bring families back together to build on their learning in the workshops, and take-home backpacks built around stories so that families can continue learning together at home. All activities ground robotics and e-textiles learning within family, written, and oral history stories from participants’ cultural backgrounds. Participating families use their stories to connect to design and engineering practices alongside their family, cultural, and language identities, in an attempt to focus on families as “cultural, historical, and political actors” (Vossoughi, Hooper, and Escudé 2016). One of our partners, Amanda, a facilitator and codesigner of the program, says:

I think the community-building aspect of Tech Tales and the centering of Indigenous knowledge sets it apart from other educational programs. The use of storytelling and art (which is very important to Native people), along with learning coding and robotics (which is exciting for the kids [and] I noticed the kids were more comfortable with and were able to teach their parents). Tech Tales creates a space where Natives [and] Indigenous knowledge [are] visible and valued.

In this article, we focus specifically on the areas of our partnership that involved Native American youth, their families, and three Native American community education groups: Red Eagle Soaring Native Youth Theater, Highline School District’s Native Education Program, and the nonprofit organization Native Girls Code. We describe our complex and highly collaborative partnership and how we consistently worked to examine our own biases and assumptions in an effort to design equitable and transformative relations between families and technology.

Participatory design research (PDR)

We describe our partnership within the framework of participatory design research, or PDR (Bang and Vossoughi 2016). PDR is a process for organizing and sustaining partnerships where all stakeholders together engage in design research and make equity central to their work. We realized that, as a team, if we wanted to design a program that itself “desettled” (Bang et al. 2012) dominant relationships between humans and technologies, we needed to organize ourselves as a group working toward equity-making in our own design processes. This meant taking seriously the need to “create ... new openings for reciprocity” between design partners and “accountability” between each other, as well as “de-settling of normative hierarchies of power” that typically can occur in university–community partnerships (Bang and Vossoughi 2016, p. 174). We found in our work (Tzou et al. 2019) that there were at least two important aspects of PDR that were central to our partnership: (1) the importance of inviting opportunities for role remediation and porosity within the partnership, and (2) working toward “more just forms of partnering” (Bang and Vossoughi 2016) that allowed for new identities, expertise, and agency to take shape in the design space. This meant that, although we might have collectively come into the project with and from pre-existing roles/positions of power, these shifted over time: Family members who came in as participants took on roles as designers and coauthors. Facilitators became codesigners and researchers. Researchers became facilitators and family participants. This kind of role porosity made way for the building of politicized trust between all of us. We use these points to organize the remainder of the article and describe our partnership work and practices.

The importance of role remediation and porosity within the partnership

Design-based research embeds hypotheses about learning within complex designs (such as a workshop series, museum exhibits, or classroom lessons) and tests those hypotheses in the implementation of those designs in real-world settings (cf. Cobb et al. 2003). During implementation, data are collected and analyzed, leading to new iterations of the design and new rounds of implementation, research, and analysis. When the design, implementation, and research are so closely linked, the boundaries between who is a “researcher,” “designer,” “teacher/facilitator,” or “participant” become blurred and porous, leading to opportunities for one to take on roles of others. Bang and Vossoughi (2016) call this role remediation, and it is a key strategy within PDR for disrupting or refusing traditional power hierarchies that can exist when university researchers enter into partnerships with community organizations. When role remediation is actively practiced within design research partnerships, power is shared among the partners in ways that allow transformative designs and new, previously unimagined roles to emerge.

Our program began in partnership with Red Eagle Soaring Native Youth Theater, which used its focus on storytelling and Indigenous Storywork (Archibald 2008) as the central component to the workshop series. From Indigenous knowledge-systems perspectives, stories are frameworks for how to know and be in the world (Archibald 2008). By grounding the workshop design in story, we intended to give families the space to build culturally and personally consequential designs through shared memories of, stories about, and relationships with places that were explored through intergenerational perspectives and making—what we have come to call family-making (Tzou et al. 2019). To center stories as the driving force behind families’ making, we began each workshop meeting with a story in which Lower Elwha Band S’Klallem educator and storyteller Roger Fernandes shared oral narratives from Coast Salish people’s traditions, rather than reading from storybooks as we had been doing with other community partners. This established the cultural storytelling that became central to the series and served as a structure for talking about story as one of our original technologies. As the project progressed, our team connected with the director of a local school district’s Native education program and with the program coordinator of Native Girls Code, who were invited to participate in professional development and codesign sessions with our team to engage with the technologies and family story-building.

In this partnership, two specific strategies supported role remediation: (1) building politicized trust (Vakil et al. 2016) between design partners, and (2) daily debriefs after each workshop session.

Building politicized trust among partners and families

Multisector partnerships such as ours work from positions of mutual trust between the participants. More specifically, because we worked from an assumption that relationships are always “power-laden” and that “our available discourse about relationships—and related constructs such as care, mutuality, respect, and trust—tend to be silent about the political dimensions of those relationships” (Vakil et al. 2016, p. 199), we found we needed to be explicit about the ways in which each of our positions lent us both unique expertise and racialized ways of approaching our work. As Vakil et al. (2016) state in the quote above, this is both an inevitable and unexamined aspect of partnerships that must be made explicit for politicized trust to be built and maintained.

Therefore, politicized trust also allows for the participatory design work to center the distributed expertise brought by specific partners—which is needed to successfully engage in such multifaceted work. (Distributed expertise indicates the many forms of expertise that different partners brought to our collective work.) The project was dependent on the trust that our partners had established with families in order to invite families to join the workshops and be participants with us in our codesign and research. This is especially important in Native American communities affected by settler colonialism through displacement from homelands and each other: New programs and people that do not work toward cultural resurgence and Indigenous survivance would not be seen as worthy of trust or attendance, especially given historically damaging relationships with universities and researchers. The university folks among us made efforts to be present at community events (e.g., Indigenous maker holiday sales, Native education STEM events and family nights) to represent our work and make personal connections so that families could learn more about us and our work. Indeed, our evaluation found that we had unexpected requests for expansion of our workshops, especially into Native American communities from local school districts. The evaluation report found that “in reaching out to Native American communities, the interest triggered multiple workshops, additional professional development training and a plan to explore the program as a part of a school district’s Native Title III literacy, bilingual/bilterate, and tribal language inclusion framework.”

Another important aspect of trust in the partnership was around trusting in each other’s expertise as we worked together toward a collaborative design product. From the evaluator’s interviews with partners, one said,

[W]e’ve all had partnerships that have failed miserably. We’ve all been at the table where … you know it isn’t going to work. I remember having talked to [my team member] about this very early on—it was absolutely very clear to me that this was a very collaborative group and a group that was very open to everyone’s expertise and ideas. It was very clear to me that everybody on our side of the table had a lot to contribute [but they were] holding back from doing that. I remember sitting [my team member] down and saying, “I really do think that they want to hear from you and you should be assertive about you know, the things that you know about your community, the things that you know about your partnerships … all the relationship[s] and that you’ve done with [one of our sites].”

A big part of developing this trust was being willing to put ourselves in vulnerable positions where all of us were trying out new designs and facilitation strategies in front of each other and with families. This concrete example of role remediation, in which university researchers and all of the designers became facilitators at some point during the workshops, was an important factor in helping facilitators feel comfortable with new forms of technology, learning with families, and engaging in design processes.

Daily debriefs and feedback

In daily debrief sessions, the entire team—researchers, facilitators, and designers—met to reflect on each workshop session: what went well, what moments of learning we observed, and what we would change for next time. This, coupled with the role remediation described above, proved to be a powerful tool for building and maintaining trust among the partners. Because we were all involved in the facilitation of the workshops, this also meant that we were giving each other feedback on our practice—often on things we were trying out in front of each other for the first time. Amanda, one of our partners in the Native education program, said,

I really appreciated the debrief at the end of every session. I felt like we all really worked together and were able to make changes from week to week based on the debriefs. During our session of TechStyle Tales we ended up rewriting the whole facilitator guide based on what happened each week. It really took the stress out of trying to get everything done and we were able to see what was important to our group, which changed our expectations. At the end it was a great learning experience for the families and the facilitators.

Collaboratively, we worked to revise the workshop series in ways that would support the needs of families and center the ways of knowing and doing, cultural values, and stories that were important to them. This included considering some very pragmatic solutions, such as providing healthy food options, being flexible with times of workshops, shortening workshop runs when needed, holding workshops at schools near families’ homes, and aligning timing and themes with summer camp events that families already participate in, which helped coordinate TechTales within the Native education program’s existing institutional structures. We also thought together about how to more closely connect cultural and family stories with e-textiles, and how to restructure the workshop sessions to highlight technologies such as sewing and storytelling through textiles. In this way, we were all playing the roles of researcher and designer, doing daily minianalyses of the implementation and tweaking designs as we went along. One of our librarian collaborators described the process in this way:

I feel completely comfortable now in the whole dynamic of things, and my hesitation was only for maybe a couple weeks, when I was like, “Oh, I don’t know.” And I think that’s just part of multiple organizations coming together. And I guess more so this feeling of like, “Let’s just give feedback and not get hurt about it.” You know? And this idea that ideas aren’t someone’s own possession, and it’s not someone’s idea, it’s our idea [emphasis added] ... And that might be just individual to me, ’cause this is kind of new to me, to treat things like that and to treat it without personalities getting pushed to the forefront. So I really like that... Yeah, just love the open sharing of feedback, and the respect that it seems everyone gives to everyone’s opinion; this is really good. So it’s really just a healthy culture in general. —Interview, June 9, 2017

From these two examples, we can see that through an intentional practice of giving feedback around the design and our own practice, we were able to get to a place where it was “our” ideas, not owned by any one person, that were put on the line and critiqued, thus opening up collaborative new ways to be accountable to each other and our collective, emerging design ideas.

Working toward “more just forms of partnering”

Working toward “more just forms of partnering” (Bang and Vossoughi 2016) allowed for the emergence of new identities, expertise, and agency to take shape in the design space. This meant that, as we described above, we were intentional about the ways that we shared power with each other and accountable to each other through relationships built on trust. This also meant that the program belonged to everyone—and we all hoped that it would evolve to best serve the communities in which it was being implemented. For example, Native education leaders continued to share about the program at professional conferences hosted by organizations such as at the National Indian Education Association and the Washington State Indian Education Association. Children talked enthusiastically about the workshops at school, spreading the word to their friends. One of our librarian partners, Ashley, said,

And it’s just been amazing to see the interest that families have had for this … And I think part of that is we’ve gotten to a place where the relationships are more stable now, and so they know us. But, you know, you never know with library programs if people are going to want to come back. And so this is the thing that just, like, continues to impress me and boggle my mind, frankly. When these kids ... they’re like, “We love TechTales. We want more!” I mean the ingredients are all there, and clearly there’s a deep interest in what we’re doing, for ... so many reasons. Not just the fancy robotic tech, the shiny stuff, but also the family time and the community-building and stuff. —Interview, June 9, 2017

Amanda, one of the coordinators for a Native education program, writes,

At the schools [where] we ran a Tech Tales session … the students were able to display their dioramas to share their work and what they learned. The kids were so proud of this. At one school (all on their own) the kids created a poster that said something like, “We love TechTales,” and had all the students who participated sign their names on it. They then got permission to hang it on the wall of their school. It felt so good to have these Native kids, who didn’t know each other before, come together and be proud to be Native and of their work in TechTales.

We found that because TechTales centered around families’ stories and ways of knowing, the community itself that was built within the workshops lived beyond the sessions, contributing to our high rate of return (80–90%) to subsequent events run by the program and multiple runs of the workshops.

Another example of just forms of partnering came when the coordinator of Native Girls Code found an opportunity to connect with us by running a TechTales series, to culminate in families presenting their projects at an event called the Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxw, which celebrated Indigenous foods and ecological knowledge and tied into one of the organization’s goals of Indigenous resurgence and survivance. Rather than insisting that the program be implemented in the way it was originally designed, we collaboratively designed an adaptation of TechTales to more closely connect to the themes of the event. By building TechTales to center cultural knowledge and practices, we were able to quickly change the project to prompt families to “tell stories about foods that are important to your family.” Participants told stories about family dinners and gardens and fruit trees in their backyards, as well as stories from cultural history. Workshop instruction included taking walks outside to observe plants both native and introduced, as well as connecting traditional stories to family practices around food (Marin and Bang 2018) (see Figure 1).

Central to the design of our program was the recognition that all learning is cultural, including our team’s, and having community partners as codesigners was central to all of our learning in how to create culturally centered learning experiences throughout all of our designed experiences. For example, the place-based work done in partnership with Native Girls Code around the Indigenous foods and medicines event was, in turn, an integral piece of the design of the TechStyle Tales, our e-textiles workshop series, in which we asked families to design e-textile tapestries about places that were important to them (see Figure 2). Our roles as designers, researchers, and facilitators were purposefully porous, which allowed for new ways of partnering that we had not originally imagined possible.

Codesign with families

Another key goal of the Tech Tales project was to develop robotics and e-textiles “engineering backpacks” that families could check out and explore at home in their own settings. Our university, science center, and library team had designed a set of e-textiles and robotics backpacks, and adoption and use were slow. We realized we were missing youth and family voices in our design of the backpacks, and the disconnect showed! This is another example of the need to constantly re-examine our own design practices with an eye toward equity. Because of our pre-existing partnership with Native Girls Code, we began a codesign process with the girls and their families (Ishimaru, Barajas-López, and Bang 2015) to design a family backpack around a story from the Yakama Nation, “I-i-esh Girl.” All of the girls had engaged in the TechTales program with their families. In the “I-i-esh Girl” story, a girl is told repeatedly that she is i-i-esh, or incompetent. She gets guidance from Grandmother Cedar, Snake, and Mountain, and learns to make a basket with designs on it. Each of these teachers guide her and teach her lessons about basketmaking and life. She then shows her village her basket and eventually teaches them how to weave cedar root baskets.

Our process began with an examination of dominant power dynamics between designers and users in an attempt to understand the ways in which bias can be built into designs (and how easy it is to be dominated by those biases), and the ways in which processes such as codesign can disrupt those power dynamics and reimagine new relationships to designs of technology.

The girls began by reflecting on their experiences working with their families in Tech Tales.

Facilitator: If we reflect on our own experiences in Tech Tales, what did you value about that?

Jones: We haven’t met any other Kiowas, so when we met Erin, we were like, “HI!” And I think that’s the reason why [we] joined [this] summer. She was like, “Hey, you know about this?” We learned a lot about our own culture from other people, so I enjoyed that.

Shawn: That’s amazing.

Tails: I also love how we learn from other dioramas because we were all talking to each other. So the idea wasn’t just for one, it was for the entire group.

Facilitator: Anything else that was valuable?

Tails: Sharing information. My step-mom doesn’t know much about coding and computers, so showing that to her was fun.

Navarro: Same with me.

Tails: The experience of sharing the knowledge between the two was fun.

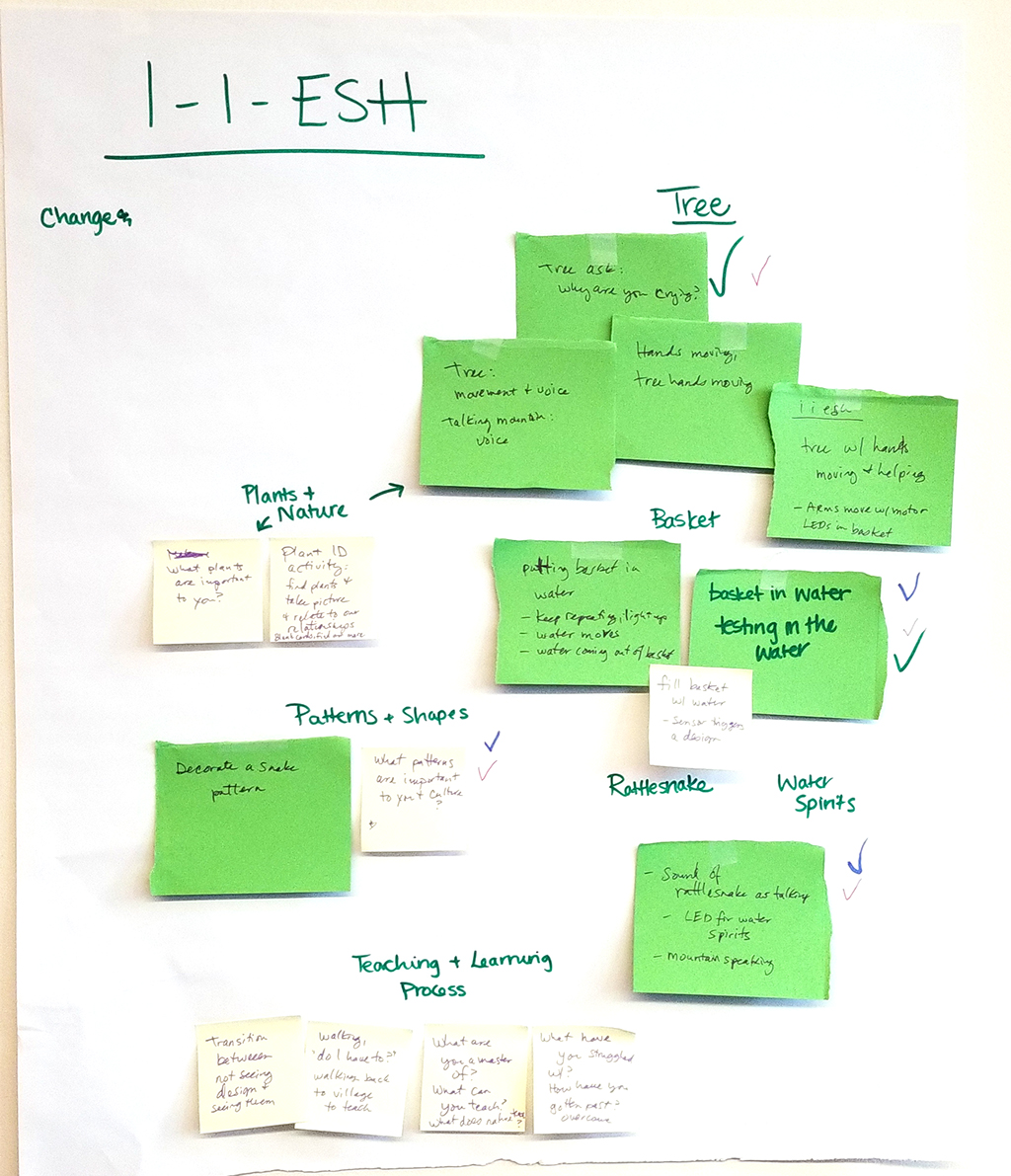

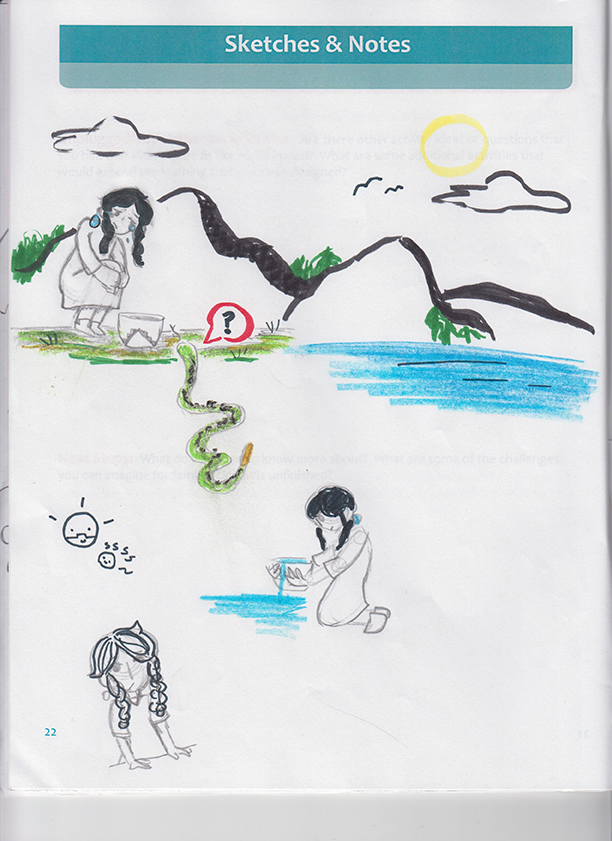

The girls then listened to several oral stories and engaged in a design “sprint,” during which they were asked to come up with five designs in five minutes around the stories they just heard. Then they had a chance to brainstorm themes in the stories and eventually decided on the Yakama story “I-i-esh Girl” as the one to design the backpack around (see Figure 3).

The codesign process continued with examining sources of connection to the story, including family practices, places, and plants. The girls prototyped sample activities such as building and animating Grandmother Cedar, Snake, and Mountain, and they designed family activities such as family walks and sharing knowledge with family members (see Figures 4 and 5).

Finally, when they had completed a prototype of an activity book, the girls invited their families to come in for a design session during which they tried out the activities, giving the girls another opportunity to rework their designs. When their book was finalized, it was presented to other Native families at a “booster day,” during which families had the opportunity to take home the backpack and try out the activities connected to “I-i-esh Girl” (see Figure 6). The final product is an example of connecting Indigenous knowledge systems around land, place, community, and family with robotics and making—using nonrobotics technologies such as stories. It is fair to say that this product could not have been designed without the combined efforts of the girls, their families, the Native educators, and university designers. This is the preface to the book:

Dear Community,

Thank you for checking out our backpack! We hope you have fun indulging in all the activities we have planned out for you. We hope that you learn more about your family and yourself through these activities.

We chose this story from the Yakama Nation. This story is important to us because of its lessons and its teachings about perseverance, not judging a person by how they act, and the value of passing on knowledge to others. We encourage you to explore these lessons in this story too.

We are Native Girls Code, a group of intertribal young Native American women (6th through 12th grade) who work on projects that explore technology and the stories of our people. You can learn more about our program on the next page.

Go code a new world!

We argue that this type of codesign process, done in community with Indigenous youth and their families in purposeful intergenerational designs, is a form of cultural resurgence that actively refuses Indigenous absence and erasure from learning environments. By centering Indigenous knowledge systems in the design of the backpacks, we have designed a set of activities in which Native American families and their practices are both (1) centered and visible, and (2) connected in meaningful ways to robotics and engineering learning. The survivance and presencing of cultural teachings, story, family and cultural practices, and Indigenous knowledge systems are everyday acts of resurgence that build Indigenous futurities for families and communities. Because of this collaboration, TechTales was woven into other events for Indigenous families and communities. It was only through the participation of Indigenous educators such as Amanda, Sara, Shawn, and Roger that family participation was possible. In this way, TechTales was part of ongoing community life within urban Indigenous families. Some evidence of this is that the Native Girls Code girls were volunteers for other community events, and that there was even cross-pollination of young people from the Highline Native Education Program to Native Girls Code, so that TechTales was continually part of larger family and community events in the greater Seattle area. “Families are the heart of Indigenous nations and communities” (Bang, Montaño Nolan, and N. McDaid-Morgan 2018, p. 2), and thus family-making—building communities of healthy Indigenous families and an Indigenous identity based on relationships to their lands, waters, culture, and teachings—is a powerful act of resurgence.

Our designs also held the deep historicity and legacy of colonial forms of education, and worked to transform them and to be accountable to them. That is, we recognized that we were not simply building cultural connections; we were centering Indigenous knowledge systems, family, and community as the foundation and the purpose of our design work, going far beyond typical deficit assumptions or demands to assimilate. As we have described in this article, through careful and intentional partnership and design work, it is possible to cultivate just forms of education that contribute to community and familial well-being and thriving.

Carrie Tzou (tzouct@uw.edu) is an associate professor of science education and director of the Goodlad Institute for Educational Renewal in the School of Educational Studies at the University of Washington Bothell.

Elizabeth Starks is a research scientist with OpenSTEM Research at the University of Washington Bothell.

Meixi is a presidential postdoctoral fellow in American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota in Mní Sota Makoce.

Amanda Rambayon (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) is the Native education coordinator for Federal Way Public Schools in Federal Way, Washington.

Sara Marie Ortiz (Pueblo of Acoma) is a writer; Native arts, culture, and education advocate; and the program manager of the Highline Public Schools Native Education Program in Burien, Washington.

Shawn Peterson (Nuu-cha-nuulth) is youth program manager at the Na’ah Illahee Fund in Seattle, Washington.

Paradise Gladstone is a member of Native Girls Code in Seattle, Washington.

Ellie Tail is a member of Native Girls Code in Seattle, Washington.

Arianna Chang is a member of Native Girls Code in Seattle, Washington.

Elise Andrew is a member of Native Girls Code in Seattle, Washington.

Xochitl Nevarez is a member of Native Girls Code in Seattle, Washington.

Ashley Braun is a children’s services librarian at the Seattle Public Library in Seattle, Washington.

Megan Bang is professor of learning sciences and psychology at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the families and community who shared their stories, time, and engagement with us. This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number DRL 1516562. Any findings or opinions expressed in this material are our own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Engineering Equity Inclusion Multicultural STEM Technology Middle School Elementary High School Informal Education Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grades 6-8 Grades 9-12