Feature

Responsive Teaching in Online Learning Environments

Using an Instructional Team to Promote Formative Assessment and Sense of Community

Journal of College Science Teaching—March/April 2021 (Volume 50, Issue 4)

By Young Ae Kim, Lisa Rezende, Elizabeth Eadie, Jacqueline Maximillian, Katelyn Southard, Lisa Elfring, Paul Blowers, and Vicente Talanquer

Online teaching and learning have become widespread in higher education over the past two decades, and accelerated during the pandemic. Although online learning is expanding and has many benefits, instructors teaching online courses must deal with a variety of demands in online learning environments. Formative assessment and sense of community have been recognized as significant factors for enhancing meaningful student learning in online platforms. While existing technological resources create opportunities for students to engage with course materials and collaborative tasks, it can be quite daunting for a single instructor to meet the needs of a diverse student population. Typically, online instructors often do not have learning assistants (LAs), and/or lack models for how to effectively deploy these human resources in online environments. In this paper we describe how the creation of online instructional teams with specialized LA roles (online learning researchers [OLRs] and online instructional managers [OIMs]) can support formative assessment and community building in online courses. The OLRs and OIMs were trained to fulfill specialized roles to support formative assessment and the development of a more cohesive community of learners had a positive impact on asynchronous online courses at our institution.

Online science teaching and learning have expanded extensively in the field of higher education over the past two decades. As institutions have been forced to quickly pivot to either synchronous remote or asynchronous online instructional modes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding how to create online learning environments that effectively support science learning for large and diverse student populations is now even more critical.

Science instructors teaching online courses face challenges and need to address a variety of tasks, including developing and guiding scaffolded online learning activities in both asynchronous and synchronous settings; coordinating and monitoring students’ remote participation; engaging students in meaningful online discussions; communicating regularly with students about materials, assignments, and due dates; and organizing and monitoring virtual collaborative groups. With so many demands, most instructors struggle to effectively create and manage a highly interactive learning environment (Palloff & Pratt, 2007), and to engage in formative assessment of student understanding to advance individual learning (Cooper et al., 2019).

Online science learning significantly improves when instructors systematically pay attention to student thinking, provide tailored feedback, and monitor student progress (Planar & Moya, 2016). Student achievement also improves with students’ active participation in a well-managed community of learners (Garrison, 2007). However, effective implementation of online formative assessment and the management of a productive learning community can be difficult, particularly when working with large numbers of students and very diverse student populations.

While existing technological resources create opportunities for students to express their ideas, engage with course materials, and collaboratively complete course tasks, it can be quite daunting for a single instructor to meet the needs of a large and diverse student population. Instructors teaching large in-person classes often rely on graduate or undergraduate learning assistants (LAs) to support the implementation of collaborative activities. These LAs traditionally help guide student work by asking guiding questions, pressing students to express their reasoning, and fostering group collaboration during instructional tasks (Otero et al., 2010). Although LAs can also facilitate and support student learning in online platforms (Cooper et al., 2019), online instructors often do not have LAs and/or effective models for how to deploy these human resources in online environments. In this paper we describe how the creation of online instructional teams with specialized LA roles can support formative assessment and community building in online science courses.

Formative assessment

Formative assessment plays a central role in supporting and enhancing student learning. This practice requires instructors to elicit and analyze student thinking, and then implement effective actions in response to the gathered evidence (Black & Wiliam, 1998). Formative assessment allows instructors to make informed instructional decisions and provide feedback to students to advance their learning (Bell & Cowie, 2001).

In online environments where instructors and students are not in the same physical space, instructors’ knowledge and implementation of effective formative assessment techniques has a significant impact on student learning (Vonderwell & Boboc, 2013). However, conducting effective online formative assessment can be challenging and time-consuming without additional instructional support. To our knowledge, LAs are rarely used in asynchronous online learning environments, even though their incorporation increases the chances for students to receive feedback, individualized attention, and guidance on their learning progress (Bourelle et al., 2017).

Sense of community

Although there is no single accepted definition, “sense of community” can be defined as “feelings of connectedness among community members and commonality of learning expectations and goals” (Roval, 2002, p. 321). Community interactions have been recognized as a significant factor for successful learning in online platforms (Reese, 2015), and thus concerns have been expressed about the common imbalance in online settings between creating effective autonomous opportunities for students to learn and opening spaces for students to interact and develop a supportive community of learners (Hamilton et al., 2004). Different teaching strategies have been suggested to develop a sense of community in online environments, such as promoting collaborative work and holding synchronous meetings (Cooper, 2009). As we will see, social interactions and the development of a sense of community can also be fostered by appropriately training and deploying specialized LAs.

Online instructional teams

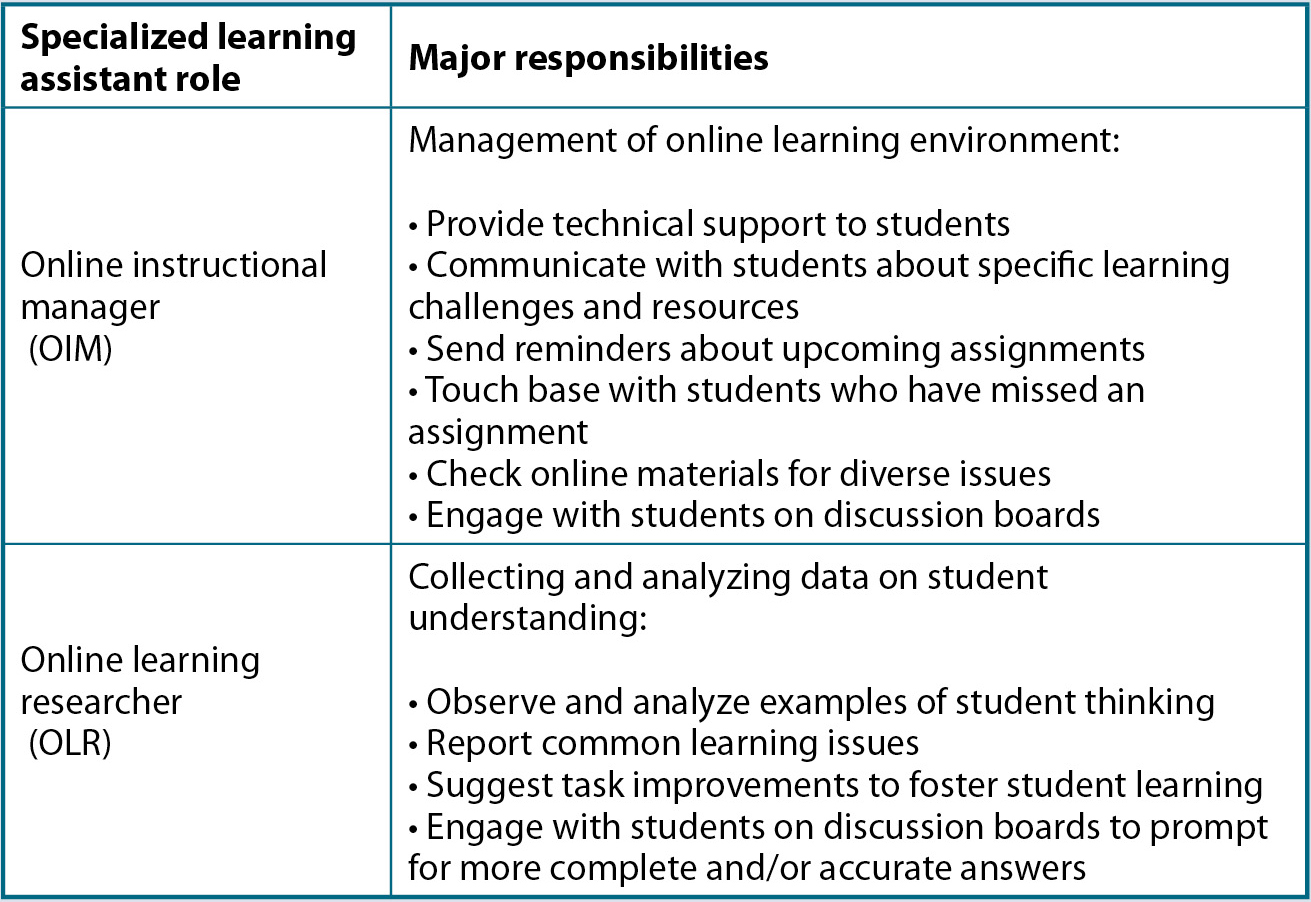

Our online instructional-team model stemmed from a larger project focused on the development and training of instructional teams that can support the use of evidence-based teaching practices in large STEM courses (Kim et al., 2019). The central goal of our model is to prepare and support instructors in the implementation of formative assessment and the development of online learning communities with the support of LAs who take on specialized roles. An online instructional team in our model is composed of one instructor working with two LAs: an online learning researcher (OLR) and an online instructional manager (OIM). These specialized LAs help the instructor manage and enrich the learning environment (OIM), as well as systematically collect and analyze formative assessment data (OLR) as students work on course activities and assignments. Table 1 describes the responsibilities of the OLR and OIM in more detail.

As shown in Table 1, specialized LAs in our model engage with students through online discussion boards in similar ways to LAs in traditional in-person courses (e.g., asking questions, pressing for explanations), but they also carry out specialized formative assessment and management tasks. LAs at our institution typically receive one or two academic credits for three or six hours, respectively, of work in the courses they support. Their activities are coordinated by the course instructor, who typically meets at least once a week with the specialized LAs to plan and reflect on course activities and student performance. Frequent communication via email is also used to organize and coordinate the work.

Specialized learning assistant roles in the online instructional-team model.

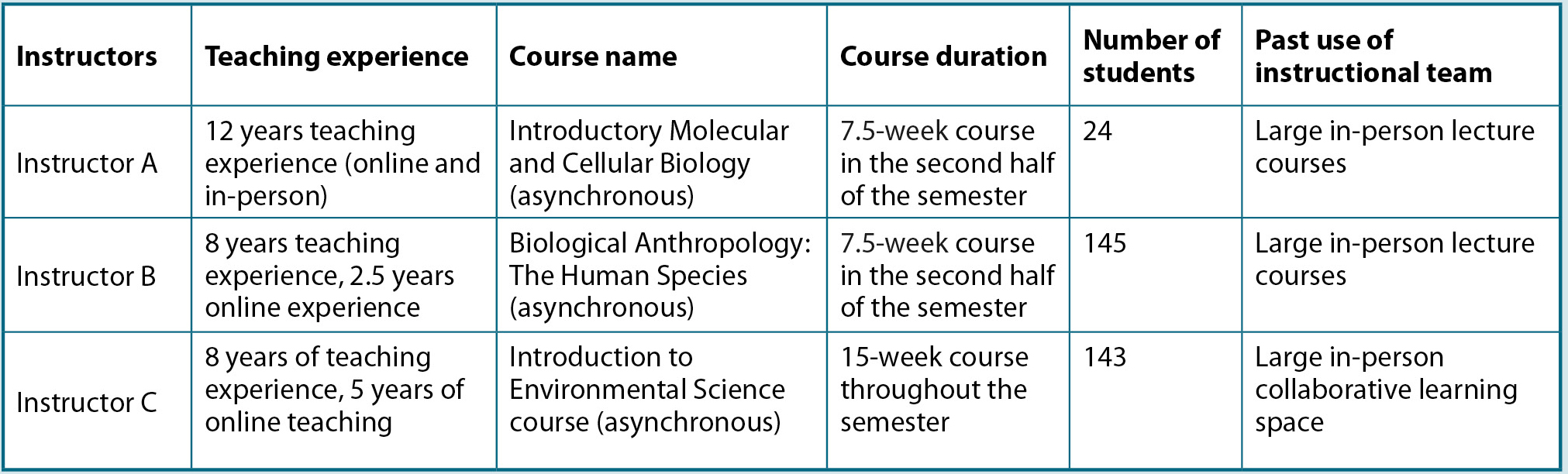

Three different undergraduate STEM classes used our online instructional-team model in the spring 2020 semester at our university, which is a large, public, Hispanic-serving, and research-intensive institution in the southwestern United States. These classes included an introductory molecular and cellular biology course, an anthropology course, and an environmental science course (see Table 2 for more information about these courses). Instructors had different levels of understanding of and experience with evidence-based teaching practices, either in-person or online, and had been previously involved in the larger NSF-IUSE project for at least one semester. In the following sections, we use the experiences in these three courses to analyze and discuss the affordances of implementing our online instructional-team model. These courses were planned to be administered as online courses and did not require modification due to the COVID pandemic.

Characteristics of observed courses and their lead instructors.

Team roles and preparation

The three courses that implemented our online instructional-team model relied on the participation of LAs trained to take on specialized roles. In this section we describe the types of support these LAs provided and the nature of the training they received.

Online Learning Researchers

The online learning researcher (OLR) role was created to help facilitate and execute efficient formative assessment and to produce responsive and reflective instruction based on evidence of student thinking. The OLR serves as both an explorer of student thinking by making observations about student work in online platforms, and as a co-planner of online learning tasks by making instructional suggestions based on these observations. The OLR is expected to carefully examine and interpret student thinking through the analysis of student products such as submissions on discussion boards, outcomes of collaborative activities, and responses to questions. Based on this analysis, the OLRs generate a list of common learning issues manifested by students in course interactions. The instructor uses this information to redesign the learning tasks with the help of the instructional team. Typically, an OLR is selected from students who previously took the course and/or have a working relationship with the course instructor.

OLRs in the observed courses were actively engaged in preimplementations of the learning tasks (e.g., making sure learning objectives of each task were posted and that discussion posts, student group VoiceThread posts, and assignments were correctly set up and easy to access by students). In some cases, OLRs were able to look at discussion posts from prior semesters and suggest more appropriate prompts. They also provided team members with formative assessment feedback from observations of weekly assignments and discussions. The OLRs created weekly reports for the instructors that included descriptions of the learning tasks, the associated learning objectives, and the perceived level of task difficulty (easy/medium/hard) based on student performance (Kim et al., 2019). These reports also summarized what the OLRs noticed in students’ responses to online learning tasks, their interpretations of student understanding based on evidence from student work, and instructional recommendations to better foster student learning.

An example of an OLR’s report from this project is included in Table 3. This report illustrates how the OLR analyzed student work to identify issues with student understanding, offered interpretations about sources of confusion, and formulated specific instructional recommendations. In this example, the OLR was a college senior serving for the first time as an OLR. She had previously taken the same online course and worked as a LA for the in-person course taught by the same instructor. This OLR regularly provided high-quality and detailed feedback on student understanding.

Online Instructional Managers

The OIM provides technical support and regularly communicate with students to help build an interactive online learning community. Part of the job of the OIM is to focus on managerial aspects of the online classes such as proofreading materials, testing links posted on the learning management system, organizing student groups, managing interactive discussions, setting up synchronized meetings, and/or posting announcements and due dates. They also help develop a sense of community by cultivating socio-emotional connections between class participants. OIMs play a mediating role by facilitating communications among instructors and students. For example, they support the establishment of interactive discussions and keep track of student participation; they also contact students who need additional support and work to involve them in the learning process. As is the case for OLRs, OIMs are selected among students who previously took the online course and/or have a working relationship with the course instructor.

OIMs in the observed courses started their work by helping set up or modify a course website (LMS) and sending emails to all the students with tips and guidance on how to succeed in the class. During the course, OIMs closely monitored the online platforms, tested assignment links, clarified instructions for diverse tasks, communicated with students who needed technical support, checked in with students who missed an assignment, and provided feedback to the main instructor when changes or updates were necessary or useful.

The activities that students completed collaboratively in online environments helped to build a sense of community (Rovai, 2002). The OIMs established direct contact with students as they worked on these tasks. They helped facilitate collaborative activities by going over instructions, emailing students reminders and tips, and following up with specific students who had not contributed to group work. OIMs also created and sent surveys soliciting student input on how to improve class activities and structure. The excerpt in Table 4 illustrates the types of communication (email) established between an OIM and students during a collaborative assignment.

An example of an online learning researcher’s analysis on student thinking.

Noticings: (What the OLR attended to and described about student work)

Ex 4:

• The splicing helps the RNA get rid of the “junk” so that it can reassemble into a different protein/length. This process causes a mature mRNA, which is a shorter length due to all the bad parts called introns being cut out.

• This student’s response doesn’t fully answer the question about how this affects proteins, but makes an attempt at answering the question

• There were not many responses like this.

I saw a great deal of responses where they were half right or were specifically explaining incorrect information regarding introns and exons, and how the protein is affected.

Interpretation: (What the OLR interpreted based on what was noticed)

It seems like the biggest things that students are hung up on is introns and exons, example 4 from student work shows a response where a student is half right, because the introns are spliced out, but sometimes so are the exons to create different combinations of codons to change the amino acid sequence. Many students seemed to be confused on this aspect of the content since I saw a lot of responses indicating this misconception where students described the intron’s being spliced out and exons being left in, but failed to recognize that exons can be spliced out as well to modify the sequence. Another issue I saw with a few students was that they didn’t attempt the problem due to confusion. I think this was probably because there is a great deal of content in this section and it can become overwhelming.

Recommendation: (What the OLR suggested to improve instruction)

I would possibly make the question more specific to elevate the difficulty, maybe ask specifically about alternative splicing and make “proteins” bold so the students will focus on that. Lots of students didn’t fully answer the question, so I think highlighting this will help students to make sure they consider the whole question. Apart from that this task is set up with other activities of varying degrees of difficulty, so I think it serves as a really good open assessment and it doesn’t necessarily need to be higher level because the content is important enough that it needs to be really understood before it can be built upon.

The work of the OIMs was not limited to supporting the instructors’ lesson plans by setting up, implementing, and troubleshooting during online instruction. They also made suggestions about how to structure the online environment to facilitate course management and enhance interactions. For example, OIMs in the observed courses proposed changes in the way students were assigned to groups and suggested changes to online tasks to foster and facilitate discussions. OIMs also wrote weekly reflections in which they analyzed and evaluated their work throughout the week and identified targets for improvement. Table 5 includes an excerpt from an OIM reflection that demonstrates how the OIM communicated and collaborated with the OLR in the same course to improve instructional activities and foster student learning.

An example of e-mails from an online instructional manager.

I have received a lot of questions about the voicethreads. The instructions for the voicethreads are on the first slide, but for some reason voicethread automatically starts on the third slide.

There are three parts to the voicethreads that you can pick from. The first option is to contribute a short paragraph answering ONE of the questions. If you log on and see that all questions are answered by your fellow students you then would do option 2. Option 2 is to evaluate and comment on one of your classmates posts! If most of the questions have replies you would then do option 3 which is to check your classmates posts for accuracy and clarity!

Voicethreads are an opportunity for you to work with your group therefore, what you do for the assignment depends on what your group has already done!

I hope this cleared up any confusion and please let me know if you have any more questions!

An example of reflection written by an online instructional manager.

The first discussion the students have is an introduction, and I have really enjoyed being able to learn more about them. It’s really nice to see their personalities rather than just their names, which can sometimes be difficult in an online course. I’ve also been able to see what some of their concerns are about the course and address them as best I can in the replies.

OLR and I have talked about how best to determine student engagement and understanding in the discussions as well as how best to apply each of our roles. We have decided that in order to support her, my main goal in replying to discussion posts will be to have students elaborate on their thinking. Many of the questions are fairly straight forward, so we want to know how students came to their answer, whether they were correct or not. This will allow OLR to evaluate engagement and allow me to help students as they need it. This elaboration is important because just because their answer may be right does not necessarily mean their thought process was.

Professional development activities

To support the implementation of the online instructional-team model, all team participants were involved in tailored professional-development activities during the semester:

- OLRs completed a one-credit course that they took prior to, or in parallel with, their online assignment. The main goals of this course are to introduce OLRs to basic principles of the learning sciences, formative assessment and task design, and to develop their abilities to observe and notice student thinking, interpret students’ expressed ideas, provide responsive feedback, offer productive instructional suggestions, and communicate their analyses through weekly written reports.

- OIMs participated in a specialized one-credit course designed to introduce them to basic principles of active learning, formative assessment, and team communication in online environments; to develop their abilities to use different online teaching and management tools and techniques; to build and support an interactive learning environment; and to identify and assess instructional challenges and devise solutions in collaboration with other team members.

- Instructors participated in a specialized online Faculty Learning Community (FLC) focused on enhancing formative assessment in online learning environments, improving task design, collaborating with different team members to support their work, and being receptive to feedback.

Team dynamics

The observed instructional teams used a variety of tools to establish, facilitate, and enhance team communication and collaboration, including weekly meetings, Google docs, and frequent e-mail exchanges. These interactions were used to provide information, give and receive feedback, generate ideas to address learning and instructional issues, and coordinate teamwork. Frequent and active collaboration helped the teams work in more cohesive and organic ways, which had a positive impact on instruction. For example, when an OLR and OIM communicated to the instructor common patterns in the ideas that students expressed in discussion posts, the team collectively identified strategies for better prompting and guiding student thinking in real time.

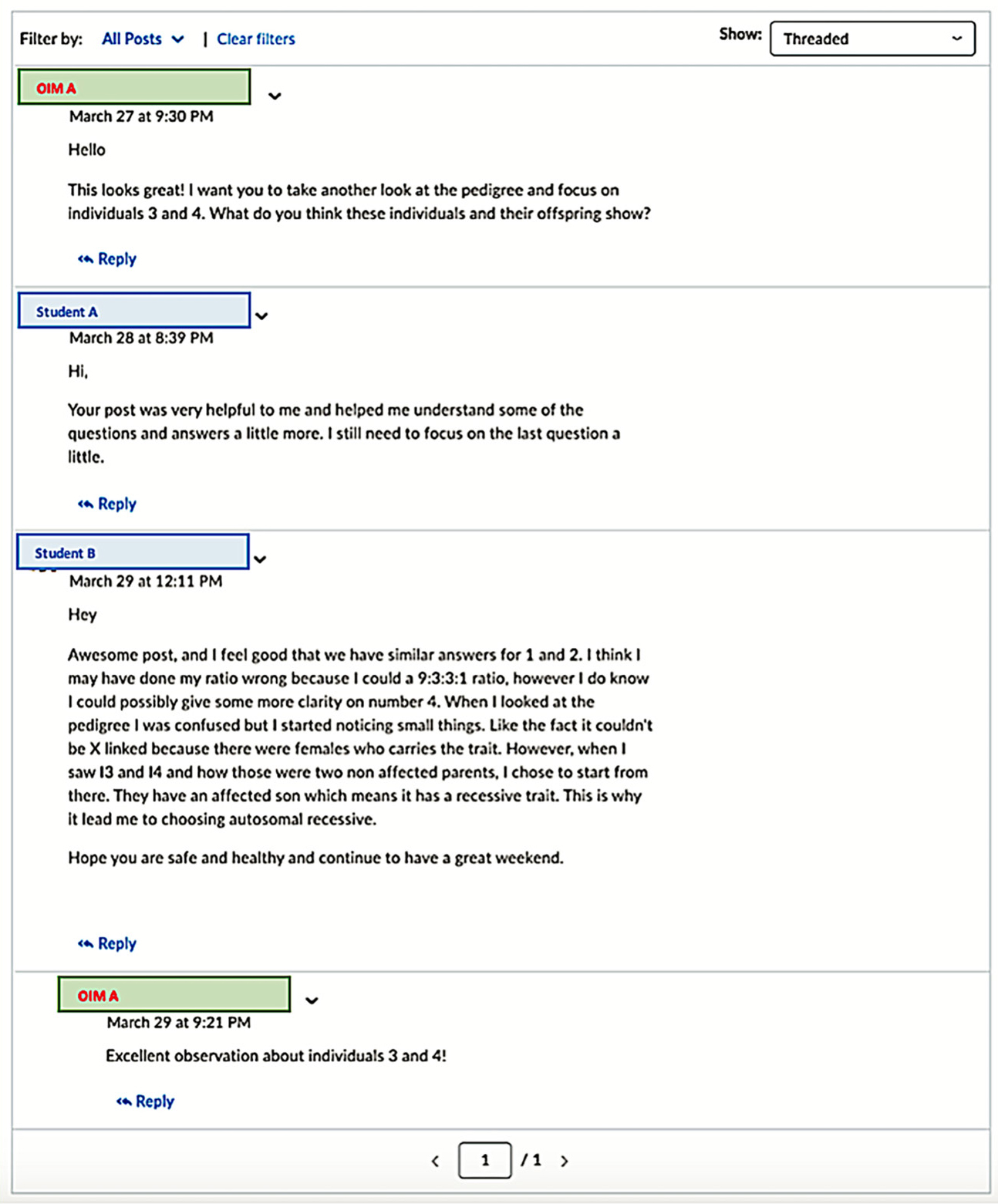

Direct and frequent interactions between the OLR and OIM were also quite beneficial. When an OLR detected that students were struggling with the course content, rapid communication with the OIM prompted this team member to contact students to provide additional guidance on a task or provide additional resources to individual students, particular groups, or the entire class. These types of interventions were recognized as helpful and effective by students, as the exchange shown in Figure 1 illustrates.

Exchange between students and online instructional manager in a discussion thread.

Students perceived the OIM and OLR as peers and were willing to engage with them in conversations and discussions about concepts and ideas introduced in the course. One of the participating instructors noticed that when she took part in the asynchronous discussions, interactions among students often stopped, as students tended to interpret the instructor’s intervention as the final answer. Online instructional teams learned to take advantage of these differential interactions to better engage students, press them to elaborate on their thinking, and guide and support them in the learning process.

Recognized benefits for instruction and student learning

The benefits of using specialized LAs in online learning were recognized by all participating instructors. Each acknowledged the positive effect of the continuous feedback and instructional support they received from their OLRs and OIMs. The following quotes from the instructors during a professional-development meeting illustrate this point:

"Adding learning assistants to my online course really changed the degree of interaction both between the students and with the instructional staff. I think having the learning assistant visible in the discussion helped humanize the course and reduced the barrier for students to reach out both to the learning assistants and to me. The addition of the learning researcher this semester has been invaluable as it helped me change discussion prompts during the semester and will inform changes I plan to implement this summer." (Instructor A)

"Using an instructional team in an online environment enabled me to add collaborative activities without feeling like they would completely overwhelm my time, and with the input of my team members who had experience with different types of online collaborative activities." (Instructor B)

"Through reading the students’ discussions, my team was able to link the discussion learning outcomes, the discussion prompts, and students’ posts or responses. They were able to identify the mismatch, which is proving useful as I revise the discussion prompts for the summer course." (Instructor C)

These instructors noticed that the participation of the OIM and OLR led to increased interactions and collaboration in different areas of the course, which strengthened the sense of community, resulted in improvements in task design based on actual evidence of student thinking, and reduced barriers for student participation. The online instructional team allowed instructors to gain continuous access to information about students’ thinking and learning, while giving them the time needed to use this information in their planning and assessment.

Through our experience using instructional teams in different learning environments (Kim et al., 2019), we have learned that the positive impact of the team on instruction depends on the extent to which the instructor builds rapport with the specialized LAs and empowers them in their roles. LAs become more motivated, take more initiative, and engage more actively with different components of the course when their work is recognized, their insights and suggestions are valued, and their ideas are used by the instructor to improve practice. As illustrated by the following interview excerpt, OLRs and OIMs involved in the project believed that their work had a positive impact on student learning:

"Because a lot of students were getting confused with the different components of the genes, we added a chart for them to kind of have all the functions in one place, and I definitely saw students performing better on those activities than in the previous semester." (OLR A)

Participating OIMs also recognized the different ways in which their actions helped and were directed at building a learning community that could support student learning:

"A lot of students reached out to me about problems they had personally and how they were good with online learning…I worked with them really closely, trying to include them in a lot of things, getting them help, making changes in the course, facilitating their interactions with other students so that they could get more out of the class than they normally would." (OIM B)

Final comments

The participation of LAs trained to fulfill specialized roles to support formative assessment and the development of a more cohesive community of learners had a positive impact on asynchronous online courses at our institution. As we continue to work on identifying and implementing best educational practices in online environments, we need to explore what structures and strategies best support the learning of diverse students in different settings. Our work shows that by helping instructors build and manage a functional instructional team that efficiently gathers formative assessment data, builds a learning community, and provides more individualized support, we can create the conditions needed to more effectively implement evidence-based and responsive teaching strategies in online platforms.

Through the implementation of our instructional-team model, we have learned that it is critical for instructors to identify LAs who are knowledgeable, motivated, and trustworthy to serve as OLRs and OIMs; instructors in our program tend to first identify students as LAs and after one semester in that role, recruit from experienced LAs to become OLRs and OIMs. In our experience, undergraduate students can serve just as well in these roles as graduate students, increasing the applicability of the model for different institution types. Instructors often struggle to relinquish control of different aspects of the planning, implementation, and assessment of the courses, and the team works best when each member develops ownership in their assigned tasks and believes their contributions are valued and have impact on student learning. Frequent interaction and open communication between team members are necessary to share information about student performance and understanding, brainstorm solutions when problems arise, and implement decisions in a quick and effective manner. Regular team meetings at a set time provides a forum for discussions and examination of evidence. ■

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all students and instructors involved in our project. Without their interest, effort, and enthusiasm to improve STEM online education, our project could not exist and move forward. This work is supported by the University of Arizona Foundation and the National Science Foundation DUE-1626531.

Young Ae Kim (joyyakim@gmail.com) is a research associate in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Lisa Rezende is an associate professor of practice in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Elizabeth Eadie is a lecturer (career track) in the School of Anthropology, Jacqueline Maximillian is an assistant professor of practice in the Department of Environmental Science, Katelyn Southard is a coordinator of teaching partnerships for student success in the Office of Instruction and Assessment, Lisa Elfring is an associate vice provost in the Office of Instruction and Assessment and an associate specialist in biology education in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Paul Blowers is a distinguished professor in the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, and Vicente Talanquer is a distinguished professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, all at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona.

Curriculum Teacher Preparation Teaching Strategies Technology Postsecondary